Home | Category: Sumerians and Akkadians

CONTEMPORARIES OF THE SUMERIANS

Elam, adjacent to Sumer in southwestern Persia and frequently treated as an extension of Mesopotamia, reached literacy by 3000 B.C.. Its capital, Susa [Shushash], exercised considerable influence in Valley affairs. This region and adjacent areas may have been the Anshan of the "Sumerian King List." [Source: Internet Archive, from UNT]

The city of Ebla, in northwestern Syria, had recently adopted Sumerian writing and wrote in Sumerian more often than in its own language [a Semitic language related to modern Hebrew and Arabic]. Ebla was excavated in 1975-76. The archaeologists found some 16000 clay tablets; 80 percent were written in Sumerian. The remainder, written in a previously unknown language, contain the oldest reference to Jerusalem and several other Hebrew proper names.

Prior to 3000 B.C., Egypt seemed to be divided into a large number of small priestlygoverned states each with its own names for commonly accepted divinities. About 3000 B.C. Egypt was unified by a conquering family out of the southern city of Thebes. The new dynasty placed its capital in the city of Memphis which lay at the point where the narrow valley of the Nile broadened into the Delta. This was the boundary, the Balance of the Two Lands (Upper and Lower Egypt); also called the Two Ladies. Half the usable soil of Egypt lay upriver (south), the rest lay down-river (north). [Source: Internet Archive, from UNT]

RELATED ARTICLES:

SUMERIANS: SUMER, HISTORY, ORIGINS, IRRIGATION africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN RULERS, GOVERNMENT, WARFARE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN LIFE, CULTURE AND LANGUAGE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN RELIGION: CITY-STATE GODS, TEMPLES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN ART AND TREASURES FROM THE TOMBS OF UR africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN CITY STATES AND CITIES: URUK, LAGASH AND GIRSU africame.factsanddetails.com ;

UR: THE GREAT CITY OF SUMER AND HOMETOWN OF ABRAHAM africame.factsanddetails.com ;

NIPPUR: THE RELIGIOUS CENTER OF MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DECLINE OF THE SUMERIANS AND THEIR FALL TO THE AKKADIANS AND ELAMITES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

AKKADIANS: EMPIRE, SARGON. LANGUAGE, CULTURE africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character” by Samuel Noah Kramer (1971) Amazon.com;

“The Age of Agade: Inventing Empire in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Benjamin R Foster (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Akkadian Empire: An Enthralling Overview of the Rise and Fall of the Akkadians”

by Enthralling History (2022) Amazon.com;

“A History of Sumer and Akkad: An Account of the Early Races of Babylonia from Prehistoric Times to the Foundation of the Babylonian Monarchy” by Leonard William King (1910) Amazon.com;

“The Elamite World” by Javier Álvarez-Mon , Gian Pietro Basello, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Iran: Rise and Fall of the Elamite and Iranian Civilization”

by Amir Reza (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerians: A History from Beginning to End” by Hourly History (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerians” by Leonard Woolley (1927) Amazon.com;

“History Begins at Sumer” by Samuel Noah Kramer (1956, 1988) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerian World” by Harriet Crawford (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerian Civilization” (2022) Amazon.com;

Akkadians and Sumerians

Kate Ravilious wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Prior to the rise of the Akkadian Empire, Mesopotamia was divided into two regions occupied by distinct peoples—the Sumerians, who lived in dozens of independent city-states along the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in southern Mesopotamia, and the Akkadians, who occupied the more rugged reaches of northern Mesopotamia. Each Sumerian city-state was ruled by a king and centered on a temple dedicated to a patron god or goddess to whom its inhabitants were devoted. Two of the most prominent Sumerian city-states were Ur, which was watched over by Nanna, god of the moon, and Uruk, watched over by Inanna, goddess of love and war.[Source: Kate Ravilious, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2022]

By contrast, the Akkadians believed that gods and goddesses were as numerous as the stars, and that they could change which deity they worshipped at any time, depending on the circumstances in which they found themselves. “This openness to new allegiances meant that when the Akkadians settled in different landscapes, they could introduce the gods who lived there into their spiritual horizon,” says Foster. “When other people came among them, new deities could set up dwellings in their heaven.” Despite worshipping many gods, the Akkadians acknowledged a supreme god, Il, and considered the goddess Ishtar—their equivalent to the Sumerian goddess Inanna—their national deity.

Until Sargon’s ascension, the Sumerians dominated culture and trade in Mesopotamia. By around 2370 B.C., the formidable king Lugalzagesi of Umma had taken command of Sumer by conquering neighboring cities such as Ur and Lagash. As Lugalzagesi rose to power in Sumer, he began to clash with the Akkadian king Ur-Zababa, ruler of the city of Kish, located on the Euphrates River around 50 miles south of present-day Baghdad.

Sumerians Versus Akkadians

Morris Jastrow said: “The Babylonians themselves recognised this distinction between the south and the north, designating the former as Sumer—which will at once recall the “plain of Shinar” in the Biblical story of the building of the tower— and the latter as Akkad. The two in combination cover what is commonly known as Babylonia, but Sumer and Akkad were at one time as distinct from each other as were in later times Babylonia and Assyria. They stand, in fact, in the same geographical relationship to one other as do the latter; and it is significant that in the title “King of Sumer and Akkad,” which the rulers of the Euphrates Valley, from a certain period onward, were fond of assuming to mark their control of both south and north, it is Sumer, the designation of the southern area, which always precedes Akkad.[Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

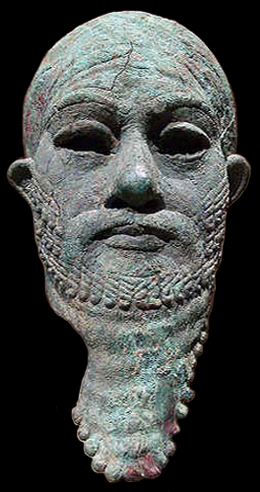

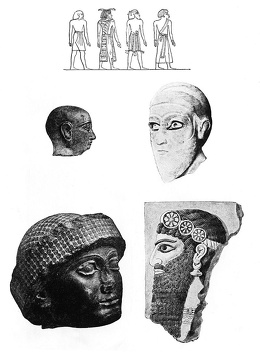

Monuments bear witness, in ethnic types, in costumes, and in other ways, to the existence of two distinct classes in the population of the Euphrates Valley—Semites or Akkadians, and non-Semites or Sumerians. The oldest strongholds of the Semites are in the northern portion, those of the Sumerians in the southern. It does not, however, necessarily follow that the Sumerians were the oldest settlers in the valley; nor does the fact that in the oldest historical period they are the predominating factor warrant the conclusion. Analogy would, on the contrary, suggest that they represent the conquering element, which by its admixture with the older settlers furnished the stimulus to an intellectual advance, and at the same time drove the older Semitic population farther to the north.

“More important, however, than any geographical distinction is the ethnological contrast presented by Sumerians and Akkadians. To be sure, the designations themselves, applied in an ethnic sense, are purely conventional; but there is no longer any doubt of the fact that the Euphrates Valley from the time that it looms up on the historical horizon is the seat of a mixed population. The germ of truth in the time-honoured Biblical tradition, that makes the plain of Shinar the home of the human race and the seat of the confusion of languages, is the recollection of the fact that various races had settled there, and that various languages were there spoken. Indeed, we should be justified in assuming this, a priori; it may be put down as an axiom that nowhere does a high form of culture arise without the commingling of diverse ethnic elements. Civilisation, like the spark emitted by the striking of steel on flint, is everywhere the result of the stimulus evoked by the friction of one ethnic group upon another. Egyptian culture is the outcome of the mixture of Semitic with Hamitic elements.

Preference by scholars was given to the non-Semitic Sumerians, to whom was attributed the origin of the cuneiform script. The Semitic (or Akkadian) settlers were supposed to be the borrowers also in religion, in forms of government, and in civilisation generally, besides adopting the cuneiform syllabary of the Sumerians, and adapting it to their own speech. Hie Sumer, hie Akkad! Halevy maintained that many of the features in this syllabary, hitherto regarded as Sumerian, were genuinely Semitic; and his main contention is that what is known as Sumerian is rnerely an older form of Semitic writing, marked by the larger use of ideographs or signs to express words, in place of the later method of phonetic writing wherein the signs employed have syllabic values.”

Struggle Between Sumerians and Akkadians

Morris Jastrow said: “The earliest historical period known to us, which, roughly speaking, is from 2800 B.C., to 2000 B.C., may be designated as a struggle for political ascendency between the Sumerian (or non-Semitic), and the Akkadian (or Semitic) elements. The strongholds of the Sumerians at this period were in the south, in such centres as Lagash, Kish, Umma, Uruk, Nippur, and Ur, those of the Semites in the north, particularly at Agade, Sippar, and Babylon, with a gradual extension of the Semitic settlements still farther north towards Assyria. It does not follow, however, from this that the one element or the other was absolutely confined to any one district. The circumstance that even at this early period we find the same religious observances, the same forms of government, the same economic conditions in south and north, is a testimony to the intellectual bond uniting the two districts, as also to the two diverse elements of the population. The civilisation, in a word, that we encounter at this earliest period is neither Sumerian nor Akkadian but Sumero-Akkadian, the two elements being so combined that it is difficult to determine what was contributed by one element and what by the other; and this applies to the religion and to the other phases of this civilisation, just as to the script. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

“When the curtain of history rises on the scene, we are long past the period when the Semitic hordes, coming probably from their homes in Arabia, and the Sumerians, whose origin is with equal probability to be sought in the mountainous regions to the east and north-east of the Euphrates Valley, began to pour into the land. The attraction that settled habitations in a fertile district have for those occupying a lower grade of civilisation led to constant or, at all events, to frequent reinforcements of both Semites and non-Semites. The general condition that presents itself in the earliest period known to us is that of a number of principalities or little kingdoms in the Euphrates Valley, grouped around some centre whose religious significance always kept pace with its political importance, and often surpassed and survived it. Rivalry between these centres led to frequent changes in the political kaleidoscope, now one, now another claiming a certain measure of jurisdiction or control over the others. Of this early period we have as yet obtained merely glimpses. Titles of rulers with brief notices of their wars and building operations form only too frequently the substance of the information to be gleaned from votive inscriptions, and from dates attached to legal and business documents. This material suffices, however, to secure a general perspective. In the case of two of these centres, Lagash and Nippur, thanks to extensive excavations conducted there, the framework can be filled out with numerous details. The general conditions existing at Lagash and Nippur may be regarded as typical for the entire Euphrates Valley in the earliest period.

“The religion had long passed the animistic stage when all powers of nature were endowed with human purposes and indiscriminately personified. The process of selection (to be explained more fully in a future lecture) had singled out of the large number of such personified powers a limited number, which, although associated in each instance with a locality, were, nevertheless, also viewed as distinct from this association, and as summing up the chief Powers in nature whereon depended the general welfare and prosperity. Growing political relationships between the sections of the Euphrates Valley accelerated this process of selection, and furthered a combination of selected deities into the semblance, at least, of a pantheon partially organised, and which in time became definitely constituted. The patron deities of cities that rose to be centres of a district absorbed the local numina of the smaller places. The names of the latter became epithets of the deities politically more conspicuous, so that, e.g., the sun-god of a centre like Lagash became almost an abstract and general personification of the sun itself. Similarly, the moon-god of Ur received the names and attributes of the moon-gods associated with other places.”

Decline of Sumerians and the Return and Fall of Ur

The Sumerians had to fight off numerous incursions by the Semite barbarians and rival Sumerian states fought over land and water rights. The Sumerians were defeated by the invading Akkadians in 2350 B.C.

Around 2250 B.C., Sargon the Great made Ur part of his Akkadian empire, one of the world's first centralized states. Akkadian, a Semitic language distantly related to the modern Arabic now spoken there, gradually replaced Sumerian as Ur's language. [Source: Michael Taylor, Archaeological magazine, March/April 2011]

Ur reemerged when the Akkadian empire collapsed. In 2047 B.C., The ensuing period historians call the Third Dynasty of Ur. Its founder, Ur-Nammu, was a great general, reformer, and innovator. He is credited with building the great Ziggurat of Ur, but perhaps his greatest achievement was creating the world’s first legal code.

Ur became the capital of its own centralized state, ruled by what historians call the Ur III dynasty. Its new king, Ur-Nammu, sought to create monuments to make the city equal to that status, and began construction of the ziggurat temple in honor of the city's patron deity, Nannar, god of the moon. But Ur-Nammu died before his greatest work could be finished, and the project was completed by his son, Shulgi. The Sumerians spread their influence westward and Ur was again powerful and remained so from about 2150 to 2000 B.C. This was the era of Abraham. By about 2000 B.C. Sumerian kings had established many colonies and Mesopotamia was "ringed by a series of satellite civilizations."

The Ur III empire founded by Ur-Nammu was overrun around 1950 B.C. by Elamites and the nomadic Amorites invading from the east, a disaster memorialized in haunting Sumerian laments:

“Ur — inside there is death, outside there is death

Inside we succumb to famine

Outside we are dispatched by Elamite blades...

Oh your city! Oh your house! Oh your people!

Turmoil descended upon the land.

The statues that were in the treasury were cut down...

There were corpses floating in the Euphrates; brigands roamed the roads.”“

Another inscription describing Ur's destruction went:

"The great storm howls above...

In front of the storm fires burn;

the people groan...

In its boulevards, where the feats were celebrated.

scattered they lay...the people

lay in heaps..."”

The city, however, endured and was eventually subordinated under successive empires of Babylonians, Kassites, Assyrians, Neo-Babylonians, Persians, and (briefly) Macedonians. At some point after the Persian invasion in 539 B.C., the Euphrates shifted to the north and east of the city, transforming Ur from prime riverfront property to the center of an expanding desert. While a tablet found at Ur that mentions Philip Arrhidaeus, Alexander the Great's half-brother, states that the site was inhabited as late as 316 B.C., it was more or less abandoned for the next 2,200 years.

Ur was abandoned in the forth century B.C., possibly after the Euphrates changed course leaving Ur high and dry in the middle of the desert. Between 2100 B.C. and today the coastline of Iraq has retreated around 100 miles, leaving Ur even more isolated from waters that once made it a great port.

Gutians

Following the fall of the Akkadian Empire around 2150 B.C., Sumer was overrun by a people from the eastern highlands known as the Gutians, also known as the Guti or Guteans. Conflict between people from Gutium and the Akkadian Empire has been linked to the collapse of the empire, towards the end of the 3rd millennium B.C. The Guti subsequently overran southern Mesopotamia and formed the Gutian dynasty of Sumer. The Sumerian king list suggests that the Guti ruled over Sumer for several generations following the fall of the Akkadian Empire. [Source: Wikipedia]

Little is known of the origins, material culture or language of the Guti, as contemporary sources provide few details and no artifacts have been positively identified. As the Gutian language lacks a text corpus, apart from some proper names, its similarities to other languages are impossible to verify. The names of Gutian kings suggest that the language was not closely related to any languages of the region, including Sumerian, Akkadian, Hurrian, Hittite, and Elamite. Most scholars reject the attempt to link Gutian king names to Indo-European languages.

The Guti appear in texts from Old Babylonian copies of inscriptions ascribed to Lugal-Anne-Mundu (fl. circa 25th century B.C.) of Adab as among the nations providing his empire tribute. These inscriptions locate them between Subartu in the north, and Marhashe and Elam in the south. Sargon the Great (r. circa 2340 – 2284 BC) also mentions them among his subject lands, listing them between Lullubi, Armanum and Akkad to the north; Nikku and Der to the south. According to one stele, Naram-Sin of Akkad's army of 360,000 soldiers defeated the Gutian king Gula'an, despite having 90,000 slain by the Gutians.

The epic Cuthean Legend of Naram-Sin claims Gutium among the lands raided by Annubanini of Lulubum during the reign of Naram-Sin (c. 2254–2218 BC).[10] Contemporary year-names for Shar-kali-sharri of Akkad indicate that in one unknown year of his reign, Shar-kali-sharri captured Sharlag king of Gutium, while in another year, "the yoke was imposed on Gutium"

The Elamites (2400 B.C. - 539 B.C.) were one of the great destroyers of Mesopotamian culture but also creators of their own culture. They emerged in what is now southwestern Iran and established a capital named Susa. They periodically battled with the Sumerians and destroyed Ur in 2000 B.C. They remained on the scene long enough to sack Babylon in the 12th century B.C. and carry the slab with Hammurabi’s legal code (See Babylonians) back to Susa.

At the high point of their power in the 13th century B.C. , the mighty Elamite ziggurat in the city of Dur Untash towered over the realm. Partly restored and found at a site called Choga Zanbil in Iran, it was one of the largest ziggurats in the world. The Elamites cultural influence continued after they were absorbed by Persia.

The Elamites were believed have grown rich from trade. Their kingdom were located between Mesopotamia and the eastern highlands that provided it with the minerals they craved: lapis lazuli, carnelian and soapstone.

The Elamites as a Middle East power lasted until 646 B.C. when the Assyrians stormed Elam and sacked Susa. They joined the Persian Empire in 539 B.C. when Cyrus the Great captured Susa.

See Separate Article: BRONZE AGE, PRE-PERSIAN AND MESOPOTAMIA-ERA IRAN factsanddetails.com

Decline of Early Mesopotamian Cultures

A decline in agriculture led to a decline in the Sumerian economy and finally a collapse of the Sumerian kingdom. By 1700 B.C. water had disappeared completely from southern Mesopotamia. The population of the region shifted to the north to Babylon.

The Mesopotamia kingdoms were ravaged by wars and hurt by changing watercourse and the salinization of farmland. In the Bible the Prophet Jeremiah said Mesopotamia’s “cities are a desolation, a dry land, and a wilderness, a land wherein no man dwelleth, neither doth any son of man pass thereby." Today wolves scavenge in the wastelands outside of Ur.

The early Mesopotamian civilizations are believed to have fallen because salt accruing from irrigated water turned fertile land into a salt desert. Continuous irrigation raised the ground water, capillary action — the ability of a liquid to flow against gravity where liquid spontaneously rises in a narrow space such as between grains of sand and soil — brought the salts to the surface, poisoning the soil and make it useless for growing wheat. Barley is more salt resistant than wheat. It was grown in less damaged areas. The fertile soil turned to sand by drought and the changing course of the Euphrates that today is several miles away from Ur and Nippur.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024