Home | Category: Sumerians and Akkadians

SUMERIANS

The Sumerians reigned over Mesopotamia from 3500 to 2300 B.C. They arrived in southern Mesopotamia sometime around 4000 B.C. They were a mysterious people. It is not known where they came from or exactly when they first appeared. Their language was like no other in the region. The Sumerians developed their system of writing sometime before 3000 B.C. and their city-state civilization lasted from 3000 to 2340 B.C.

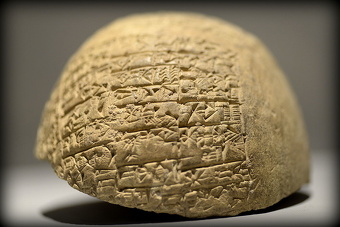

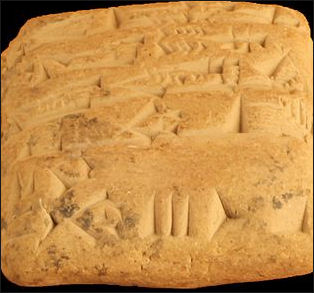

The Sumerians are the name of the people. Sumer is the name of the place. Most of what is known about the Sumerians is based on sculptures, cuneiform tablets and other artifacts unearthed in ancient Sumerian cities. Sumerian King List, principal source of knowledge about Sumerian culture. The Babylonians and Assyrians and other Mesopotamians and Near Eastern cultures that followed the Sumerians adapted Sumerian writing to their own languages and used Sumerian religion and literature. Sumerian scientific and cultural knowledge was also passed on to the Babylonians and Assyrians.

In their own language, the Sumerians called themselves sag giga (salmat qaqqadi), or "black-headed ones." The word “Sumer” is derived from Akkadian word “Shumeru.” John Alan Halloran of sumerian.org wrote: “It is not known why the Akkadians called the southern land Shumeru. The Sumerians called it ki-en-gir15 (literally, 'place of the civilized lords'). The etymology of the Akkadian term is unknown. It could possibly be a dialectal pronunciation of the Sumerian word kiengir. This possibility is suggested by the Emesal dialect form 'dimmer' for the word 'dingir'.” [Source: John Alan Halloran, sumerian.org]

During the third millennium B.C., Sumeria developed into an imperial power. Marcos Such-Gutiérrez wrote in National Geographic History: For centuries, Sumerian culture flourished and was the dominant power in Mesopotamia. Across the region that is now southern Iraq, powerful city-states emerged, towering ziggurats rose, sweeping epics were told, and golden jewelry adorned the rich and powerful. Dominance and control would shift among its glorious cities as the years rolled by. The civilization reached its peak in the late third millennium B.C and then gradually fell away. In 2340 B.C., the Semitic peoples of Akkadia conquered Mesopotamia, and by 1950 B.C. the ancient civilization had disintegrated. Sumerian civilization and its achievements would be forgotten for millennia, until archaeologists began exploring the region in earnest in the 19th and 20th centuries. Glorious finds in the area revealed the richness and complexity of this ancient culture and allowed scholars to see how Sumerian influences cascaded through the civilizations that followed it. [Source: Marcos Such-Gutiérrez, National Geographic History, August 25, 2023]

RELATED ARTICLES:

SUMERIAN RULERS, GOVERNMENT, WARFARE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN LIFE, CULTURE AND LANGUAGE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN RELIGION: CITY-STATE GODS, TEMPLES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN ART AND TREASURES FROM THE TOMBS OF UR africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN CITY STATES AND CITIES: URUK, LAGASH AND GIRSU africame.factsanddetails.com ;

UR: THE GREAT CITY OF SUMER AND HOMETOWN OF ABRAHAM africame.factsanddetails.com ;

NIPPUR: THE RELIGIOUS CENTER OF MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DECLINE OF THE SUMERIANS AND THEIR FALL TO THE AKKADIANS AND ELAMITES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

AKKADIANS: EMPIRE, SARGON. LANGUAGE, CULTURE africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character” by Samuel Noah Kramer (1971) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerians: A History from Beginning to End” by Hourly History (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerians” by Leonard Woolley (1927) Amazon.com;

“History Begins at Sumer” by Samuel Noah Kramer (1956, 1988) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerian World” by Harriet Crawford (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerian Civilization” (2022) Amazon.com;

Sumerian Achievements

The Sumerians were pioneers in the development of city life, civic organization, law and monumental architecture. They had the oldest known written language, created the first historically attested civilization and invented cuneiform writing, the sexagesimal system of mathematics (an ancient system of counting, calculation, and numerical notation that used powers of 60 much as the decimal system uses powers of 10), and the socio-political institution of the city state with bureaucracies, legal codes, division of labour, and a form of currency. [Source: Elizabeth Knowles, The Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, Encyclopedia.com]

Major cities founded by the Sumerians included Ur, Kish, and Lagash. There were few trees or even big rocks in the region settled by the Sumerians.The most readily available materials were sand and clay and reeds from marshes. Their buildings were constructed of mud brick and wood, not stone, so very little of the ancient cities remain excepts for some foundations.

Mysterious Sumerians

The origin of the Sumerians is unknown. Their language is unrelated to any other language thus far discovered but has some things in common with Finnish and Turkish. Before recorded history the Sumerians moved into Babylonia from the South. The Sumerians drove out the earlier residents (or, as is more likely, they kept the peasants in their previous status, and made collaborators of of some of the "city folk."). The peoples driven from the Valley by the Sumerians may have been the Subartu. Whoever they were, they may have been the first of the Valley's residents to become literate. [Source: Internet Archive, from UNT, piney.com ]

The Sumerians were neither Indo-Europeans (Aryans) nor Semites. The Semites had thick hair and long beards; the Sumerians had shaved heads and faces. These Sumerians overran southern Babylonia as far north as Nippur and became the ruling race. They added the worship of their gods on top of the worship of the deities of the conquered cities, but the earlier elements of these local deities persisted even in Sumerian thought. As a result the shaved Sumerians picture their gods with hair and beards.

History of the Sumerians

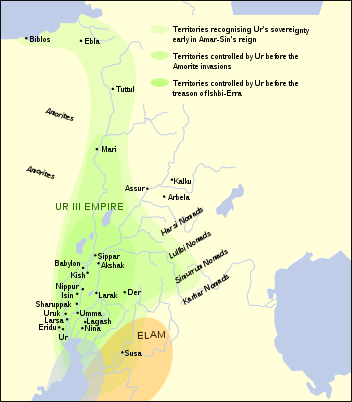

Map of Sumer in the Ur III period

The Pre-Babylonian (Sumerian) Period begins about 3100 B.C. and continued to the rise of the city of Babylon, about 2050 B.C. This period was a time of succesive city kingdoms. After settling in Babylonia, the Sumerians developed a system of writing. It was at first hieroglyphic, like the Egytian system. Afterwards the Semites, who still controlled Kish and Agade in the north, and had been reinforced by people (Semites) from Arabia, adapted this writing to their own language. These pictures degenerated into symbols which we know as "cuneiform" characters — all letters are made with wedge-shape characters. [Source: Internet Archive, from UNT, piney.com ]

Samuel Noah Kramer (1897–1990) was one of the world's leading Assyriologists and an expert in Sumerian history and Sumerian language. He wrote: History of a legendary character begins in Sumer in the first half of the third millennium with the three partly contemporaneous dynasties of Kish, Erech (Uruk), and Ur. Some of the outstanding rulers of this era were: Etana of Kish, a figure of legendary fame; Enmerkar, Lugalbanda, and Gilgamesh of Erech, three heroic figures celebrated in a cycle of epic tales; and Mes-anne-padda of Ur, the first ruler from whom we have contemporary inscriptions. The three-cornered struggle among these cities so weakened Sumer that for a century or so it came under the domination of the Elamite people to the east. It recovered during the reign of Lugal-anne-mundu of Adab (c. 2500), who is reported to have controlled not only Sumer but some of the neighboring lands as well.

Authentic history, recorded on significant contemporary documents, begins with the second half of the third millennium. The earliest-known ruler from this period is Mesilim (c. 2475), noted for arbitrating a dispute between the two rival city states, Lagash and Umma. In the century that followed, Lagash played a dominant political role in Sumer; under one of its rulers, Eannatum (c. 2425), it became for a brief period the capital of Sumer. Its last ruler, Urukagina (c. 2360), was history's first-known social reformer; the documents from his reign record a sweeping reform of a whole series of bureaucratic abuses and the restoration of "freedom" to the citizens. Urukagina was defeated by Lugal-zagge-si (c. 2350) of Umma, an ambitious king who moved his capital to Erech and succeeded in making himself ruler of all Sumer. By this time, however, Semites from the north and west had infiltrated northern Sumer, and one of their leaders, Sargon (c. 2325), defeated Lugal-zagge-si and conquered all Sumer, and indeed much of ancient western Asia. Later generations claimed that his power extended even to Egypt and India. Sargon built a new capital, Agade (biblical, Akkad), and following his reign the land came to be known as "Sumer and Akkad."

The Dynasty of Akkad endured for over a century. Toward the end of its rule, Sumer suffered a humiliating invasion by the Gutians from the Zagros hills, and thus came under Gutian domination for close to a century (c. 2200–2100). Throughout much of this period, however, the city of Lagash seemed to flourish, and one of its rulers, Gudea (c. 2140), whose statues and inscriptions have made him one of the figures best known to the modern world, exercised considerable power in spite of the Gutian overlordship.

Sumer was finally liberated from its Gutian yoke and, under the Third Dynasty of Ur, founded by Ur-Nammu (c. 2100), a king noted as the promulgator of the first-known law code, it experienced a remarkable renaissance. Ur-Nammu's son, Shulgi (c. 2080), was one of the great monarchs of the ancient world. A rare combination of statesman, soldier, administrator, and patron of music and literature, he founded Sumer's two leading academies at Nippur and Ur. The last of the dynasty, the pious, pathetic Ibbi-Sin (c. 2015), was a victim of infiltration by the nomadic Amurru from the west, of unrelenting military attacks by the Elamites from the east, and of traitorous intrigues by his own governors and generals. Ur was finally destroyed and Ibbi-Sin carried off to Elam, a calamity long mourned by the poets of Sumer in dolorous laments. Following the destruction of Ur, Ishbi-Irra, one of Ibbi-Sin's traitorous generals, established a dynasty in Isin (c. 2000) that lasted for some 200 years. Isin was destroyed by Rim-Sin (c. 1800), a king of neighboring Larsa, who, in turn, was subjugated by Hammurapi (c. 1750) of Babylon. With the reign of Hammurapi, the history of Sumer comes to an end, and that of Babylonia begins.

Origins of the Sumerians

In the period 5500–4000 B.C., much of Mesopotamia shared a common culture, called Ubaid. after the site where evidence for it was first found, al-Ubaid, a tell near Ur. The Ubaidians were agriculturists. Nothing is known about their language except for traces left in a number of geographical names and words, relating to agriculture and technology, borrowed by the Sumerians. Following the settlement of the land by the Ubaidians, nomadic Semites from the north and west infiltrated the land as settlers and conquerors. The Sumerians themselves did not arrive until about 3500 B.C. from their original home, which may have been in the region of the Caspian Sea. Sumerian civilization, therefore, is a product of the ethnic and cultural fusion of Ubaidians, Semites, and Sumerians; it is designated as Sumerian because at the beginning of recorded history it was the Sumerian language and ethos that prevailed throughout the land. [Source: Samuel Noah Kramer, Encyclopaedia Judaica, Encyclopedia.com]

John Alan Halloran of sumerian.org wrote: “My belief that mastery of irrigation agriculture is what marked the Sumerians, that they moved down from the middle of Mesopotamia, site of the Samarra culture. The simplest words of Sumerian include words for dikes and channels. Archaeologists are now saying that Choga Mami ware [a kind of pottery associated with the early Sumerians] is transitional between Samarra pottery and Ubaid pottery. This agrees with my belief. [Source: John Alan Halloran, sumerian.org]

Distribution of haplogroup J2 Y-DNA

“The History and Geography of Human Genes by Cavalli-Sforza et al. finds distinctive genes in Kuwait and speculates that Kuwaitis are the genetic descendants of the Sumerians....A 2011 study of the DNA of 143 Marsh Arabs and a large sample of Iraqi controls arrived at the following conclusions: "Evidence of genetic stratification ascribable to the Sumerian development was provided by the Y-chromosome data where the J1-Page08 branch reveals a local expansion, almost contemporary with the Sumerian City State period that characterized Southern Mesopotamia. On the other hand, a more ancient background shared with Northern Mesopotamia is revealed by the less represented Y-chromosome lineage J1-M267*.

Overall our results indicate that the introduction of water buffalo breeding and rice farming, most likely from the Indian sub-continent, only marginally affected the gene pool of autochthonous people of the region. Furthermore, a prevalent Middle Eastern ancestry of the modern population of the marshes of southern Iraq implies that if the Marsh Arabs are descendants of the ancient Sumerians, also the Sumerians were most likely autochthonous and not of Indian or South Asian ancestry." [Source: "In search of the genetic footprints of Sumerians: a survey of Y-chromosome and mtDNA variation in the Marsh Arabs of Iraq", Nadia Al-Zahery1, Maria Pala1, Vincenza Battaglia1, Viola Grugni1, Mohammed A Hamod23, Baharak Hooshiar Kashani1, Anna Olivieri1, Antonio Torroni1, Augusta S Santachiara-Benerecetti1 and Ornella Semino, BMC Evolutionary Biology 2011, 11:288.]

“The late S.N. Kramer was very proud of his idea that the Sumerians came from somewhere else and enjoyed a Heroic Age in Sumer which he believed had parallels among other migratory peoples. The idea that the Sumerians were late invaders is, however, probably wrong. There are actually good Sumerian or Akkadian etymologies for most of those city names and if you look in my lexicon you can see the Sumerian etymologies for the Tigris and the Euphrates river names. Nippur comes from an Akkadian word that means "ferry-boat", so it was the site of a river crossing. Thorkild Jacobsen wrote an article about the Sumerian etymologies of Eridu, Ur, and some other cities. The Halaf culture of northern Mesopotamia was characterized by colorfully glazed pottery that is completely different from Ubaid pottery, so I don't know anyone who thinks that it was a predecessor other than chronologically to the southern Ubaid culture.

“The Sumerians either called themselves the 'civilized children' or the 'black-headed people'. sag-gi6(-ga): black-headed people; Sumerians ('head' + 'black' + nominative; cf., dumu-gir15/gi7 and ki-en-gi(-r); ki-en-gir15/gi7(-r)). un sag-gi6: black-headed people = Sumerians ('people' + 'heads' + 'black'). dumu-gir15/gi7: freeborn man, Sumerian [in contrast to slaves from foreign countries] ('child' + 'native group'). It seems like originally it may have been sang-gi7, but consonant harmony changed gi7 to ngi6, thereby changing the meaning from 'civilized, native group' to 'black'.

Sumerian Connections to the Bible

Samuel Noah Kramer wrote: There are a number of biblical words that go back in all probability to Sumerian origin: ʿ anak (Sumerian naga), "tin"; ʿ eden (edin), "Eden"; gan (gan), "garden"; hekhal (egal), "palace"; iddeqel (idiglat), "Tigris"; ʾ ikkar (engar), "farmer"; kisse (guza), "chair"; mala (mala ), "sailor"; perat (buranum), "Euphrates"; shir (sir), "song"; tammuz (dumuzi), "Tammuz"; tel (dul), "mound"; tifsar (dubsar), "scribe"; tomer (nimbar), "palm-tree." [Source: Samuel Noah Kramer, Encyclopaedia Judaica, Encyclopedia.com]

Adam and Eve cylinder seal Far more significant are the literary motifs, themes, patterns, and ideas that go back to Sumerian prototypes: the existence of a primeval sea; the separation of heaven and earth; the creation of man from clay imbued with the breath of life; the creative power of the divine word; several "paradise" motifs; the Flood story; the Cain-Abel rivalry; the Tower of Babel and confusion of tongues; the notion of a personal, family god; divine retribution and national catastrophe; plagues as divine punishment; the "Job" motif of suffering and submission; the nature of death and the netherworld dreams as foretokens of the building of temples.

Not a few of the biblical laws go back to Sumerian origins, and in such books as Psalms, Proverbs, Lamentations, and the Song of Songs there are echoes of the corresponding Sumerian literary genres. Sumerian influence on the Hebrews came indirectly through the Canaanites, Assyrians, and Babylonians, although to judge from the Abraham story and the often suggested abiru-Hebrew equation, the distant forefathers of the biblical Hebrews may have had some direct contact with the Sumerians. The Biblical word for Sumer is generally assumed to be Shinar (Heb. ש נְעָר; Gen. 10:10). It has also been suggested that Shinar represents the cuneiform šum (er) -ur (i), i.e., Sumer and Akkad, and that the biblical equivalent of Sumer is Shem (from cuneiform šum (er)); hence the anshe ha-shem of the days of yore in Genesis 6:4.

Ur and Abraham

Biblical Abraham was born under the name Abram in the Sumer city of Ur in Mesopotamia (in present day Iraq). According to Genesis, Abraham was the great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great grandson of Noah and was married to Sarah.Genesis 11:17-28, reads “Terah Begot Abram, Nahor, and Haran, and Haran begot Lot. And Haran died in the lifetime of Terah his Father in the land of his birth, Ur of Chaldees.”

According to Genesis Abraham, his father, Sara and his orphaned nephew Lot moved from Ur to Haran, 600 miles away in present-day Turkey. The journey probably took months. The Bible offers no explanation why Abraham left Ur. Sarah was originally names Sarai. She received her name Sarah from God.

The Koran and Jewish tradition suggest the following reason for Abraham’s departure from Ur: King Nimrod of Ur (or Babylon) tried to have young Abraham burned alive for refusing to worship local gods. Divine forces intervened to protect him. According to a Jewish story King Nimrod was told a prophet that a man would rise up against him and his pagan religion and Nimrod believed that Abraham might be this man and forced him to flee.

Sumer and the Sumerian City-States

Transfer of cattle from Ur Sumer (sometimes called Sumeria) is the name of an area, which embraced city-states like Ur, Nippur and Uruk. Sumer was located in southwest Asia in present-day Iraq and comprised the southern part of Mesopotamia. From the 4th millennium B.C. it was the site of city states which became part of ancient Babylonia. In the Bible Sumer is called Shinar.

The Sumerians didn’t establish an empire like the Romans did. They lived in a bunch of independent city-states like the Greeks. The first cluster Mesopotamian settlements were established in ancient Sumer around 3,500 B.C. These settlement grew into the city states of Ur (home of Abraham and the Chaldees in the Bible), Eridu, Uruk (Biblical city of Erech), Lagash, Nippur, Umma, Sippar, Larsa, Kish, Adab, and Isin.

Around 3000 B.C. powerful local leaders became the kings of the city-states. Kingdoms were forged by these kings whose armies conquered neighboring city states with lances and shields. The city-states battled each other. Strong rulers were able to conquer their neighbors. Weak rulers were defeated. As time went on different city-states — such as Lagash, Uruk, Ur — were dominant. In general, however, the Sumerians appeared to have relatively peaceable during their 1,200 years of dominance in Mesopotamia. They didn’t make an effort create a large empire.

Sumer's independent city-states amassed great agricultural wealth by harnessing the waters of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers into irrigation canals that they used to raise crops. Each city was seen as the property of one of the gods in the Sumerian pantheon, and the city’s ruler served as that god’s representative. The most important and prominent structure in a Sumerian city was the temple to its main god. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2020]

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: Girsu, which was a major city in the city-state known as Lagash, belonged to Ningirsu, the heroic warrior god charged with combating demons and maintaining the cosmic order. A number of the chaos-inciting demons that Ningirsu fought were believed to inhabit a mountain in the northeastern reaches of the Sumerian world, in the region of present-day Turkey where the Tigris and Euphrates originate. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2020]

“By defeating the demons in this mountain, Ningirsu tames the two rivers and makes irrigation possible on the food plain,” says Rey. “Thus, he is considered a god of irrigation and agriculture, as well as the personifcation of foods.” One of the creatures Ningirsu was renowned for vanquishing was Imdugud, a thunderbird, or an eagle with the head of a lion. Rather than killing Imdugud, though, Ningirsu tamed it and adopted it as his avatar.

Irrigation in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamians developed irrigation agriculture. To irrigate the land, the earliest inhabitants of the region drained the swampy lands and built canals through the dry areas. This had been done in other places before Mesopotamian times. What made Mesopotamia the home of the first irrigation culture is that the irrigation system was built according to a plan, and an organized work force was required to keep the system maintained. Irrigation system began on a small-scale basis and developed into a large scale operation as the government gained more power.

The Sumerians initiated a large scale irrigation program. They built huge embankments along the Euphrates River, drained the marshes and dug irrigation ditches and canals. It not only took great amount of organized labor to build the system it also required a great amount of labor to keep it maintained. Government and laws were created distribute water to make sure the operation ran smoothly.

Archaeologists have found 3,300-year-old plow furrows with water jars still lying by small feeder canals near Ur in southern Iraq. Craig Simpson wrote in The Telegraph: Their civilisation revolved around water and depended on advanced irrigation that directed water from the Tigris and Euphrates rivers into canals that watered fields providing the food necessary to support urban life. According to ancient writings, it was part of an order maintained by gods who in turn were maintained by sacrifice and libations, but when the gods abandoned Girsu, the Sumerians were forced to effect their own salvation. [Source: Craig Simpson, The Telegraph, November 18, 2023]

Samarran Culture, Choga Mami and the Origins of Irrigation

The Samarra culture is a Copper Age culture in northern Mesopotamia that existed roughly dated from 5500 to 4800 B.C.. Partially overlaping with the Hassuna and early Ubaid periods, . Samarra its is associated most with the sites of of Samarra, Tell Shemshara, Tell es-Sawwan and Yarim Tepe. At Tell es-Sawwan, evidence of irrigation—including flax—establishes the presence of a prosperous settled culture with a highly organized social structure. The culture is primarily known for its finely made pottery decorated with stylized animals, including birds, and geometric designs on dark backgrounds. This widely exported type of pottery, one of the first widespread, relatively uniform pottery styles in the Ancient Near East, was first recognized at Samarra. The Samarran Culture was the precursor to the Mesopotamian culture of the Ubaid period. [Source: Wikipedia]

Choga Mami a Samarran site in Diyala Province, Iraq about 110 kilometers northeast of Baghdad, shows some of world’s earliest evidence of irrigation. The first canal irrigation operation dates to about 6000 B.C.. The site,, has been dated to the late 6th millennium B.C., was occupied in several phases from the Samarran culture through the Ubaid. Buildings were rectangular and built of mud brick, including a guard tower at the settlement's entrance. Irrigation supported livestock (cattle, sheep and goats) and arable (wheat, barley and flax) agriculture.

Choga Mami yields important evidence on the chronological relationships between North and South Mesopotamian cultures and their connections with Iran. The introduction of irrigation, new types of grain, foreign ceramic styles and domestic cattle are all located in the Choga Mami phase, a late manifestation of the Samarran Period in lowland Mesopotamia. This chronological identification thus also suggests the source of these innovations: migration from the lowlands.

map of canals

Sumerians Invented Water Flumes Thousands of Years Earlier than Previously Thought

Ancient Sumerians invented a “civilisation-saving” water channel 4,000 years ago, a British Museum project has revealed.Craig Simpson wrote in The Telegraph: Archaeologists working at the ruined city of Girsu in Iraq have discovered the true function of a mysterious structure created by the civilisation. The inhabitants of the ancient city created a device known as a “flume” to propel water to distant locations where it was needed, thousands of years before this technology was thought to have been discovered. [Source: Craig Simpson, The Telegraph, November 18, 2023]

The Sumerians, who were the first people to tell early versions of the biblical story of the flood, appeared to have devised this “anti-drought machine” in an effort to preserve a way of life threatened by vital canals drying up. Ebru Torun, an architect and conservationist working with the British Museum team in Iraq, said: “This is absolutely one of a kind. There is no other example of it in history, really, until the present day.”

In modern-day Girsu, the only signs of water are the scars of desiccated wadis cut into the yellow dust, the remains of homes, temples and palace walls reduced by time and the desert rains first to slurry, then powder. It is believed the structure was built by the final generations living in Girsu in a last attempt to save their home from becoming unlivable. Their desperation is revealed by archaeological evidence, which shows that they redirected all water courses into a single canal and through the device to maximise flow.

Dr Sebastien Rey, an archaeologist and the project’s leader in Iraq, explained: “They are struggling for one thing and that is water. All of the texts tell us about the crisis. It is not just a bridge, it’s an anti-drought machine, anti-collapse. The canals are drying up, silting up, one by one. This is one last desperate attempt to save themselves. The monumental scale of the structure shows how important this project was to them. It is a civilisation-saving effort.”

How the Sumerian Water Flumes Worked

Craig Simpson wrote in The Telegraph: The latest research conducted in this remote corner of Iraq, its least populated province, have now revealed that the structure that channelled a 100-foot-wide canal into a 13-foot-wide passage would have created a feature known as the “Venturi” effect, something that would not be theorised by scientists until the late 18th century. It refers to the increase in velocity of liquids as they pass through a constricted “throat”, and can be put into practice with structures known as “Venturi flumes”. [Source: Craig Simpson, The Telegraph, November 18, 2023]

aerial view of a Girsu water flume

The Girsu structure is one such flume, which would have accelerated water flow and forced the water to more distant locations downstream where it was needed, including the neighbouring administrative capital of Lagash. Ms Torun said: “When you do this to water it’s going to go further, it’s going to accelerate. They knew all the key factors, they knew what they were doing. We have not seen any other example of this in ancient Mesopotamia. If you look at the walls of the bridge, they are inclined outwards. This further increases flow, but no one knew this, as far as we know, until the 20th century.”

The device is formed of two symmetrical mud-brick structures about 130 feet long, 33 feet wide and with 11-foot-high walls arranged in two opposing curves bending outwards. The twin buildings appeared so purposeless to archaeologists in the 1920s that the site was simply named “the enigmatic structure”, with more daring theories suggesting that it might have been a bizarrely arranged temple.

The Girsu flume even has a “sharp drop” at its centre, a feature present in modern flumes that would have better facilitated the Venturi effect and which the Sumerians appear to have been aware of.There is evidence that the structure was built on a previous construction that followed the same design, suggesting that water-accelerating technology was known to the Sumerians millennia before it was thought to have been created.

The shifting climate and changing river courses in Mesopotamia in the second millennium B.C. were too powerful to be held back by Sumerian ingenuity, however. In the temple complex, a band of white can be seen in the soil layers made up of deconsecrating ash that Sumerians scattered in the holy places that they believed had been abandoned by the gods, marking the point in 1750 B.C. when the inhabitants of Girsu abandoned the city.

Sumerian Sea Travel and Boats

According to Archaeology magazine: The Sumerians are known for having established one of the world’s earliest agricultural civilizations, but a chance discovery in southern Iraq suggests they also traveled the seas and conducted long-range trade. In 2016, researchers from the Sapienza University of Rome were excavating at the site of Abu Tbeirah when they spied clay bricks in a foxhole. In the years since, they have found remains of brick ramparts along with docks and an artificial basin that served as the town’s port. Dating back more than 4,000 years, it is the oldest harbor ever to have been discovered in Iraq. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2018]

The researchers have also found carnelian beads from India along with alabaster vases and other objects that must have been procured overseas. The finds are surprising because the extensive records Sumerians left behind in the form of cuneiform tablets include a great deal of information about farming, but little about seafaring. “The texts speak mainly of agriculture because it required the most organization,” says excavation codirector Franco D’Agostino. Archaeology is helping to make clear how important seafaring was to them as well.

In the early 2020s, an Iraqi-German team recently excavated the remnants of an ancient boat that was exposed by erosion in 2018 near the Sumerian city of Uruk in southern Iraq. The boat, which measures 23 feet long and up to 4.5 feet wide, was found on the city’s outskirts in an area once covered by fields, canals, and small settlements. The vessel sank around 4,000 years ago near the bank of a river that has long since silted up. Although the organic material used to construct the boat—likely wood, reeds, or palm leaves—has completely decayed, the material left clear impressions in a surviving layer of bitumen that was applied to the boat as waterproofing. Researchers carefully documented the excavation of the fragile find before moving the vessel’s remnants to the Iraq Museum in Baghdad for conservation and study. To see an image of the boat's excavation, [Source: Benjamin LEONARD, Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2022]

Sumerian Genes Found in Okinawa, Japan?

According to the sources cited below, the Y-chromosome J2#1 haplotype is found in the gene pool of Okinawan populations, southern Japan (frequency 1.12 percent). This haplotype shows match patterns in populations of the Caucasus, and areas along the northern coast of continental Europe, such as The Netherlands, Hamburg, Estonia and Poland. [Source: [Source: Rootsweb Haplogroup J J2 page, Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

According to a 2011 study “In search of the genetic footprints of Sumerians: a survey of Y-chromosome and mtDNA variation in the Marsh Arabs of Iraq”, Haplogroup J, with its two branches J1-M267 and J2-M172, is a Middle Eastern Y-chromosome lineage dating to about 30,000 years ago with a common ancestral origin of Marsh Arabs (located in Southern Iraq) and Southern Arabian peoples. From focal points of high frequency in the Near East the haplogroup has a frequency distribution that shows radial decreasing clines (i.e. migratory paths) toward the Levant area, Central Asia, the Caucasus, North Africa, and Europe.

digital reconstruction of a Girsu water flume

The study also determined that although both clades (J1-M267 and J2-M172) evolved in situ and participated in the Neolithic revolution, their different geographic distributions suggest two distinct histories: a more ancient background shared with Northern Mesopotamia revealed by the less represented Y-chromosome lineage J1-M267* but which alone characterizes more than 80 percent of the Marsh Y-chromosome gene pool; the J1-Page08 branch that reveals a local expansion around 4,000 years ago, almost contemporary with the Sumerian City State period that characterized Southern Mesopotamia; and J2-M172 which has been linked to the development and expansion of agriculture in the wetter northern zone and is also considered the Y-chromosome marker for the spread of farming into South East Europe.

It is not clear how this J2 lineage arrived in Japan, whether via the Caucasus or maritime seafarers or along the Silk Route of Central Asia. The article “Is there a deep history Sumerian connection or Near Eastern layer to Japanese prehistory?” considers the existence of any archaeological or anthropological evidence to support the arrival in southern Japan of an early J2 Sumerian/Middle Eastern lineage.

Like haplogroups E3b and G, haplogroup J and its subclades originated in the Near East and spread across Europe and the Mediterranean during the Neolithic. It is common among Semitic populations, and includes the Cohen Modal Haplotype – the paternal genetic legacy of the Jewish priestly class. It is also present in North Africa, Arabia and the Caucasus. / J Haplotype #1: The highest frequencies for this haplotype occur in Mediterranean countries, among American Hispanics and in the Caucasus. /

J2 Haplotype #1: The match pattern for this haplotype includes the Caucasus, and areas along the northern coast of continental Europe, such as The Netherlands, Hamburg, Estonia and Poland. The haplotype may have originated with a Jewish population, or from an admixture that had been present in a Germanic population thousands of years ago. The hits in the U.S. heartland and Southern Ireland suggest that it diffused into the British Isles to a greater degree than many J2 haplotypes. The closest matches for DYS385a,b values of 12,16 are, in fact, with Oregon and Southern Ireland. One cautionary note about this haplotype however. The DYS393 value of 13 causes it to resemble some R1a haplotypes, so we can’t rule out convergence.

Geographical Locale (percent): North Caucasus [Rutulian]: 4.55; Indiana [European-American]: 2.94; Oregon [European-American]: 2.86; Maryland [African-American]: 1.37; Netherlands: 1.15; Okinawa, Southern Japan: 1.15; Southern Ireland: .93; Hamburg, Northern Germany: 88; Lublin, Eastern Poland: .75; Tartu, Estonia: .75; Buenos Aires, Argentina [Europeans] .67; Dusseldorf, Westphalia .67; Lombardy, Northern Italy: .55; Sweden: .25; Freiburg, Baden-Wurttemburg: .23; Berlin, Brandenburg :.18.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Girsu flumes from the British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024