Home | Category: Sumerians and Akkadians / Art and Architecture

SUMERIAN ART

The Sumerians created lovely alabaster vases with carved heads, alabaster and stone figurines, cylinder seals made with precious stones, gold ornaments, gold jewelry and musical instruments decorated with gold and semi-precious stones. The were expert metal workers adept at fashioning silver and gold. An inlaid gold vessel in the form of an ostrich egg might have held food and drink.

Most of the Sumerian works of art have been excavated from graves. The Sumerians often buried their dead with their most prized objects. They also produced some of the first portraits. Gudea, the Sumerian king of Lagash, who lived around 2100 B.C., is remembered with a series of seated sculptures that are among the most famous Sumerian works of art. A life size one made of black diorite is particularly nice.

Much of the stuff found by Sir Leonard Woolley’s excavations at Ur is now in the British Museum. Some is at the Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. One of the most famous objects there is Great Lyre from the King’s Grave. It is a gold-and-lapis-lazuli bull’s head and inlaid shell plaque attached to a re-created wooden frame.

The soundbox of a lyre unearthed in a grave in Ur, dated at 2700 B.C., contains an amusing comic-book-like rendering of animals made with a mosaics of shell, gold, and silver on a background of lapis lazuli. The image is believed to a depiction of a poplar fable. A finely carved gypsum head of an unknown subject, dated 2097 to 1989 B.C., features eery eyes colored with blue pigments.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SUMERIANS: SUMER, HISTORY, ORIGINS, IRRIGATION africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN RULERS, GOVERNMENT, WARFARE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN LIFE, CULTURE AND LANGUAGE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN RELIGION: CITY-STATE GODS, TEMPLES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN CITY STATES AND CITIES: URUK, LAGASH AND GIRSU africame.factsanddetails.com ;

UR: THE GREAT CITY OF SUMER AND HOMETOWN OF ABRAHAM africame.factsanddetails.com ;

NIPPUR: THE RELIGIOUS CENTER OF MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DECLINE OF THE SUMERIANS AND THEIR FALL TO THE AKKADIANS AND ELAMITES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

AKKADIANS: EMPIRE, SARGON. LANGUAGE, CULTURE africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Mesopotamia: Ancient Art and Architecture” by Zainab Bahrani (2017) Amazon.com;

“Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur” by Richard L. Zettler and Lee Horne (1998) Amazon.com;

"Sumerian Art, Illustrated by Objects from Ur and Al-'Ubaid” by The British Museum and Terence C. Mitchell (1969) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerian World” by Harriet Crawford (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character” by Samuel Noah Kramer (1971) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerians: A History from Beginning to End” by Hourly History (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerians” by Leonard Woolley (1927) Amazon.com;

“History Begins at Sumer” by Samuel Noah Kramer (1956, 1988) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerian World” by Harriet Crawford (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerian Civilization” (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Art and Architecture of Mesopotamia” by Giovanni Curatola, Jean-Daniel Forest, Nathalie Gallois (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient (The Yale University Press Pelican History of Art) by Henri Frankfort , Michael Roaf, et al. (1996) Amazon.com;

“Art of the Ancient Near East: A Resource for Educators” by Kim Benzel, Sarah Graff, Yelena Rakic Amazon.com;

“Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus”

by Joan Aruz and Ronald Wallenfels (2003) Amazon.com;

Sumerian Treasures at Iraq National Museum

Bull's head of the Queen's lyre from Pu-abi's grave PG 800, the Royal Cemetery at Ur, British Museum

The Sacred Vase of Warka is a one-meter-high, carved alabaster vase, dated at around 3000 B.C. Discovered by German archaeologists in the 1940s near the city of Samawa, it contains some of the world’s earliest references to religious ritual, social hierarchy, the natural order and urban economy. Carvings in five distinct layers wrap around the vase with the three main ones from bottom to top being: 1) abundant fields, flocks, water, plants in the city state of Uruk; 2) nude men bringing offering to a temple; and 3) the King presenting an offerings to Inana, the great Sumerian goddess of fertility, war, love and success, and her ritual marriage to a king. Warka is another name for Uruk.

The Warka head, also dated to around 3000 B.C., is regarded as one of the most refined Sumerian pieces. It is a life-size white marble head of a Sumerian woman that originally had a headdress and eyes and eyebrows made of inlaid gold and lapis lazuli. Dubbed the “Mona Lisa of Mesopotamia,” it may have been part of a statue of Inana.

The Little King is a seven-inch-high figurine, also dated at 3000 B.C., and found under a temple in Uruk. Possibly a portrait of En, one of Uruk’s ruler, it is made of alabaster and has inlaid eyes made of lapis lazuli and shell.

The Statue of Sumerian Worshiper, dated at 2600 B.C., is a stone statue originally placed in a temple as prayer for its donor. The Stone Statue of a Sumerian Scribe, dated at 2400 B.C., is a representation of an official of the city-state of Ginsu who may have founded a system of weights and measures.

Golden treasures from Ur include the Harp of Ur, a Sumerian gold harp dated at 2500 B.C. It contains a golden head of a bearded bull that is attached to a soundbox decorated with colored stones and pieces of shell. It was found in the tomb of Puabi in Ur. A golden helmet, dated to 2500 B.C., belonging to King Meskalamdug is a fine example of Mesopotamian metalwork. It was found in the royal cemetery of Ur.

Other treasures include a statue from Ur representing a Sumerian deity, dated to 2600 B.C.; a bronze sculptured head of a woman from Uruk, dated at 3000 B.C.; gilded bulls with long beards and tile inlays; numerous cuneiform inscriptions; a mask of Nara-Sin, the first Mesopotamian ruler to declare his divinity; a collection of gold necklaces, bracelets and earrings from a Sumerian dynasty, date 2500 B.C.; and a wig-like helmet made of pure gold that was probably worn by a king. Some Sumerian seals are more than 5000 years old. One lion hunt seal tells the story of the beginning of the kingship and the beginning of the state. A man is pictured in a turban and long skirt fighting lions with a spear and bow and arrow. The theme of a king fighting lions was passed on to other Mesopotamian kingdoms.

Sumerian Sculpture

Most Sumerian sculpture are doll-size human or deity figurines found in graves in cemeteries in Ur, Eridu, and Umma al-Ajarib. Sumerian figurines were usually made of stone or alabaster. The figures usually have stiff-looking postures and often had large owl-like eyes that make the figures look as if they are in a trance.

Describing a sculpture of the Sumerian king Gudea, New York Times art critic Holland Carter wrote: “He is a clean shaven youth with tapering fingers and slender toes, and a large pillbox crown. His face is serene and alert, but his shoulders are slightly hunched, and one bare arm is flexed. Everything about him is tensed, as if he is holding his breath.

The prize of the University of Pennsylvania collection is “Ram Caught in a Thicket," a lapis lazuli sculpture of a blue-horned, shell-fleeced billy goat standing in its hind legs in front of a carved wooden tree wrapped in gold foil. The 4,600 year-old structure was found in Ur.

Statuettes, circa 2700 B.C., found at the Abu Temple in Eshnunna include bug-eyed figures, some with a bare shaven heads and others with grandmother bun-style hairdos. A limestone statuette found at the Inanna Temple in Nippur depicts a woman with her hands clasped in worship. Some very old sculptures from Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asia bear features that appear to have been influenced by Sumer sculptures.

Royal Tombs of Ur

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “In 1922, C. Leonard Woolley began to excavate the ancient city of Ur in southern Mesopotamia (modern Iraq). By the following year, he had finished his initial survey and dug a trench near the ruined ziggurat. His team of workmen found evidence of burials and jewelry made of gold and precious stones. They called this the "gold trench." Woolley recognized, however, that he and his workforce had insufficient experience to excavate burials. He therefore concentrated on excavating buildings and it wasn't until 1926 that the team returned to the gold trench. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "Ur: The Royal Graves", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003]

“Woolley began to reveal an extensive cemetery and gradually uncovered some 1,800 graves. Most of the graves consisted of simple pits with the body laid in a clay coffin or wrapped in reed matting. Vessels, jewelry, and personal items surrounded the body. However, sixteen of the graves were unusual. These were not just simple pits but stone tombs, often with several rooms.

“There were many bodies buried in the graves, surrounded by spectacular objects. Woolley called these the "Royal Tombs." From his finds he attempted to reconstruct the burials. One tomb possibly belonged to the queen Pu-abi. Her title and name are written in cuneiform on a cylinder seal found close to her body. When she was buried, soldiers guarded the entrance to the pit while serving ladies crowded the floor. Woolley discovered their bodies. He suggested that they might have taken poison. Pu-abi herself was buried in a stone tomb at the far end of the pit. The finds from the Royal Graves were eventually divided between the British Museum, London, the University Museum, Philadelphia (both sponsors of the dig), and the Iraq National Museum, Baghdad.

Manuel Molina Martos wrote in National Geographic History: The discovery of the tombs was big news not only for the quantity and craftsmanship of the objects found but also for the light they shed on the grisly nature of Sumerian burial practices. The finds included exquisitely crafted jewelry and musical instruments, as well as large numbers of bodies: servants and soldiers entombed alongside their dead sovereigns. [Source: Manuel Molina Martos, National Geographic History, May 22, 2019]

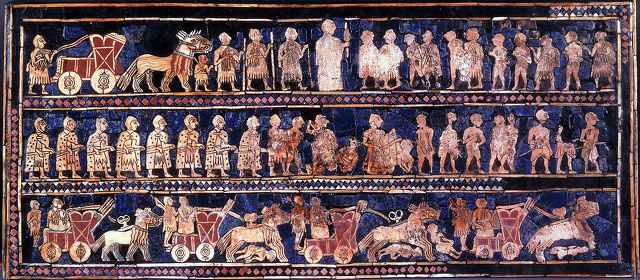

Ur chariot on the standard of Ur

During the digging season of 1926–27,Woolley and his colleague Max Mallowan had uncovered hundreds of tombs from the city’s necropolis. At first only human remains and a few grave goods were unearthed, certainly not the riches they had been anticipating. But then, toward the end of the season, they made a spectacular find. Hidden among some bronze weapons was a magnificent gold dagger with a lapis lazuli handle. Next to it, a gold sack contained a set of musical instruments also made of gold. Never before had objects of such value and artistic quality been found at a Sumerian site.

On finding an underground chamber made of stone, expectations ran high. Woolley suspected it could be the tomb of a royal figure. As they continued to excavate, the team uncovered a tunnel dating to a later time. Work continued, and Woolley’s efforts would be rewarded with the discovery of PG800, a pristine burial. The discoveries came fast and furious. Digging in the so-called Death Pit area of the tomb, the archaeologists discovered five bodies, adorned with grave goods, lying together on rush matting. A few yards away, they found ten more bodies. These were women wearing ornaments of gold and precious stones. These carefully arranged cadavers also held musical instruments. Beside them were the remains of a musician who held a stunning lyre. The sound box of the instrument was incrusted with carnelian, lapis lazuli, and mother-of-pearl. On its wooden frontpiece was mounted the stunning golden head of a bull with eyes and beard of lapis lazuli.

Death Pits of Ur

During Sir Charles Leonard Woolley’s excavation of Ur from 1922 to 1934, any burial without a tomb chamber was given the name ‘death pit’ (also known as ‘grave pits’). A total of six burials were assigned as ‘death pits’. For the most part these were tombs and sunken courtyards connected to the surface by a shaft. These ‘death pits’ were thought to have been built around or adjacent to the tomb of a primary individual.[Source: Ancient Origins, June, 2018]

According to Ancient Origins: Arguably the most impressive death pit excavated by Woolley and his team was PG 1237, which Woolley dubbed as ‘The Great Death Pit’, due to the number of bodies that were found in it. These bodies were arranged neatly in rows and were richly dressed. It is commonly believed that these individuals were sacrificial victims who accompanied their master / mistress in the afterlife. It is unclear, however, if they had done so voluntarily.

According to the University of Pennsylvania: “PG1237 included 6 men and 68 women. The men, near the tomb’s entrance, had weapons. Most of the women were in four rows across the northwest corner of the death pit; six under a canopy in its south corner; and, six near three lyres near the southeast wall. Almost all wore simple headdresses of gold, silver, and lapis; most had shells with cosmetic pigments. Body 61 in the west corner was more elaborately attired than the others. Half the women (but none of the men) had cups or jars, suggestive of banqueting. Body 61 held a silver tumbler close to her mouth. The neat arrangement of bodies convinced Woolley the attendants in the tombs had not been killed, but had gone willingly to their deaths, drinking some deadly or soporific drug. He suggested that in so doing they were assured a “less nebulous and miserable existence” than ordinary men and women.

“A study conducted by the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology on the skulls of a woman and a soldier, however, found signs of pre-mortem fractures caused by a blunt instrument. One of the theories emerging from this finding is that the dosage of poison consumed by some of the attendants was not enough to kill them, and therefore they were struck on their heads to prevent them from being buried alive.

Sumerian Art From Grave of Queen Pu-abis in Ur

Some of the most spectacular Sumerian art was unearthed from the grave of Queen Pu-abi, a 4,600-year-old site excavated by British archaeologist Leonard's Woolleys' team in Ur. The pieces found there included lyres decorated with golden bull heads and a wiglike helmet of gold described above as well as earrings, necklaces, a gold dagger with a filigree sheath, a toilet box with a shell relief of lion eating a wild goat, inlaid wooden furniture, a golden tumbler, cups and bowls, and tools and weapons made of copper, gold and silver.

Manuel Molina Martos wrote in National Geographic History: As the dig progressed, Woolley came upon yet more treasures in the tomb: weapons, tools, numerous vessels of bronze, silver, gold, lapis lazuli, and alabaster—even a gaming table. In the center of the space lay an enormous wooden chest, several yards long, which had probably been used to store garments and other offerings that had long since rotted away. [Source: Manuel Molina Martos, National Geographic History, May 22, 2019]

Inside the burial chamber itself lay the body of a woman on top of a funeral bier. She was covered with amulets and jewelry made of gold and precious stones. Her elaborate headdress was made of 20 gold leaves, lapis lazuli and carnelian beads, as well as a large golden comb. Near the body lay a cylinder seal that bore an inscription from which the archaeologists were able to identify the woman: Queen Puabi (in his notes, Woolley referred to her as Shubad because of a mistranslation). The seal made no mention of her husband, which led some to believe she could have been a queen in her own right. Alongside Puabi lay the bodies of two of her servants. In addition to her treasures and servants, Puabi was interred with her makeup, including a silver box that contained kohl, a black pigment used as eyeliner.

Queen Pu-abi was buried, wearing, a necklace of gold and lapi lazuli, 10 gold rings, garters of gold and lapis lazuli, and a striking cape made of gold, silver, lapis lazuli, agate and carnelian beads. She was buried with 11 other women, presumably her attendants. Queen Pu-abi’s headdress was made of gold ribbons, carnelian and lapis lazuli beads, bands of gold leaves, all surmounted by a high comb of silver with eight-petaled gold rosettes, symbols of goddess Inana. Archaeologists working at the Queen Pu-abi site also unearthed a mosaic with figures made from limestone, muscle shell and mother of pearl, on a lapis background that shows a military procession with troops driving their chariots over captured enemies.

Ram Caught in a Thicket

The Ram in a Thicket is a pair of figures excavated at Ur, in southern Iraq, which date from about 2600–2400 B.C.. One is in the Mesopotamia Gallery of the British Museum in London; the other is in the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia, The pair, more accurately correctly described as goats, were discovered lying close together in the 'Great Death Pit' (PG 1237) in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, by archaeologist Leonard Woolley during the 1928–9 season. [Source: Wikipedia]

Wooley wrote: Gaiety of another kind enters into the polychrome—one might almost say chryselephantine—figure of a goat which we have called for obvious reasons ‘the ram caught in a thicket’. The head and legs of the animal are of gold, the belly of silver, the body-fleece of pieces of carved shell but the fleece on the shoulders of lapislazuli, and of lapus lazuli are the eye-pupils, the horns and the beard; the tree to whose branches its front legs were chained is of gold and it stands on a pedestal whose sides were silver-plated and its top of pink and white mosaic (PL 36)... The elegance and lightness of the figure harmonise perfectly with the brilliance of its colour—there is all the agility of the goat translated into art, but at the same time it is a dedicated animal and possesses a curious solemnity; the momentary poise which, as the drawings on the shell plaques prove, the artist knew so well how to seize is here frozen into permanence and life has become statuesque.[

When it was discovered, the 45.7-centimeter (18 inch) figures had been crushed flat by the weight of the soil above them and the inner wooden core had decomposed. This wooden core had been finely cut for the face and legs, but the body had been more roughly modelled. Woolley used wax to keep the pieces together as it was excavated, and the figure was gently pressed back into its original shape. The ram's head and legs are layered in gold leaf which had been hammered against the wood and stuck to it with a thin wash of bitumen, while its ears are copper which are now green with verdigris. The horns and the fleece on its shoulders are of lapis lazuli, and the body's fleece is made of shell, attached to a thicker coat of bitumen. The figure's genitals are gold, while its belly was silver plate, now oxidised beyond restoration. The other figure's genitals are presumed silver, corroded, and therefore missing. The tree is also covered in gold leaf with gold flowers.

According to Archaeology magazine: The statuettes commonly referred to as “Ram Caught in a Thicket” (2500 B.C.) may well be associated with what is known from later texts (2nd millennium B.C. as the (daily) determining-of-the-fates ritual that occurred at sunrise. Symbolic elements (tree, rosette, leaf, possible mountain), and motifs (quadruped facing a tree) occur in other media—glyptic, musical instruments—and their meaning informs the unique com-bination of elements found in these two statuettes. It is proposed that the statuettes are offering stands. The composition as a whole represents a sacred landscape rather than a charming genre scene. It is likely that the statuettes were associated with the daily ritual of the determining of the fates, which would push the later attestations of that ritual and the cosmological view behind it back to the mid-third millennium BC. [Source: Archaeology magazine, March-April 2021]

Standard of Ur

The Standard of Ur is a trapezoidal wooden box incorporating lapis lazuli, shell and red limestone into the depiction of various figures on its surface. Its function is debated, although Woolley believed it to be a military standard, explaining this object's current name. divided formally into 3 registers with all figures on a common ground. The standard uses hierarchy of scale to identify important figures in the compositions[Source: Wikipedia]

On each side of the standard, the pictorial elements are considered part of a narrative sequence Read from left to right, bottom to top on one side of the standard, starting with the lowest registers, there are men carrying various goods or leading animals and fish towards the top register where larger seated figures take part in a feast accompanied by musicians and attendants. The other side depicts a more militaristic subject where men in horse-drawn chariots trample over prostrate bodies and soldiers and prisoners process up towards the top frieze where the central personage is designated by his large scale, punctuating the border of the upper most frieze.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except irrigation picture from Michigan State University

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, Archaeology magazine, Live Science, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024