Home | Category: Sumerians and Akkadians

EVERYDAY LIFE IN LAGASH

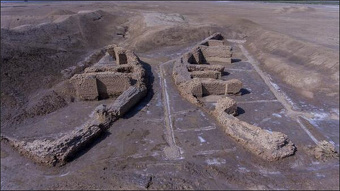

Close to the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, Lagash flourished from 2900 B.C. to 2300 B.C. as a political, religious and industrial population center. It was dubbed the "garden of the gods" by the ancients for its fertility and gave rise to a string of Sumerian cities dating back to the early dynastic period. "Lagash was one of the important cities of southern Iraq," Iraqi archaeologist Baker Azab Wali told AFP "Its inhabitants depended on agriculture, livestock, fishing, but also on the exchange of goods," he said. Lagash is about 320 kilometers (200 miles) southeast of Baghdad. The archaeological site in Lagash is massive, with remains stretching across 6.5 kilometers (four miles) according to the University of Pennsylvania. [Source: CBSNews, February 16, 2023]

Holly Pittman, the Lagash Project Director and Curator at the Penn Museum in Pennsylvania, and the field director, Sara Pizzimenti, an associate professor at the University of Pisa in Italy, were leading excavations in Lagash focused on understanding the lives of the city’s non-elite inhabitants. The project focused on neighborhoods where everyday people lived about 5,000 years ago.

The Miami Herald reported: In what remains of one of these non-descript neighborhoods, Pizzimenti uncovered a burnt structure. Although a number of ancient pottery kilns were found in the area, this structure was different. It was an oven, Pittman explained. Archaeological excavations of the non-elite neighborhood uncovered streets, alleyways, houses, pottery kilns and many more artifacts, according to the Lagash Archaeological Project’s website about the fall 2022 season. The team uncovered clay seals, stone tools, tokens, beads, jar stoppers and almost 37,000 pottery shards.

Many excavations of ancient Sumer focused on palaces or temples, places that reveal the lives of the elite class, Pittman said. Her team wants to understand the rest of society “how these people structured their economic life, their domestic life, their public and their private lives.” To do this, her team has plans for three future excavation seasons focused on various lower class neighborhoods in Lagash.

People played games from a very early date. Prehistoric games included senet, an Egyptian game and Mancala, which originated in Jordan. Dice have been found at Akkadian sites. The Akkadians were contemporaries of the Sumerians.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SUMERIANS: SUMER, HISTORY, ORIGINS, IRRIGATION africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN RULERS, GOVERNMENT, WARFARE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN RELIGION: CITY-STATE GODS, TEMPLES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN ART AND TREASURES FROM THE TOMBS OF UR africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN CITY STATES AND CITIES: URUK, LAGASH AND GIRSU africame.factsanddetails.com ;

UR: THE GREAT CITY OF SUMER AND HOMETOWN OF ABRAHAM africame.factsanddetails.com ;

NIPPUR: THE RELIGIOUS CENTER OF MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DECLINE OF THE SUMERIANS AND THEIR FALL TO THE AKKADIANS AND ELAMITES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

AKKADIANS: EMPIRE, SARGON. LANGUAGE, CULTURE africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Stephen Bertman (2002) Amazon.com;

“Learn to Read Ancient Sumerian: An Introduction for Complete Beginners” by Joshua Aaron Bowen (2019) Amazon.com;

“A Manual of Sumerian Grammar and Texts” by John Hayes (1990) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character” by Samuel Noah Kramer (1971) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerians: A History from Beginning to End” by Hourly History (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerians” by Leonard Woolley (1927) Amazon.com;

“History Begins at Sumer” by Samuel Noah Kramer (1956, 1988) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerian World” by Harriet Crawford (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerian Civilization” (2022) Amazon.com;

5,000-Year-Old Tavern Found in Lagash

In February 2023, archaeologists working in southern Iraq announced that they had uncovered the remains of a tavern dating back nearly 5,000 years in the Sumerian city of Lagash. The joint team from the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Pisa discovered the remains of a primitive refrigeration system, a large oven, benches for diners and around 150 serving bowls. [Source: CBSNews, February 16, 2023]

"So we've got the refrigerator, we've got the hundreds of vessels ready to be served, benches where people would sit... and behind the refrigerator is an oven that would have been used... for cooking food," project director Holly Pittman told AFP. What we understand this thing to be is a place where people — regular people — could come to eat and that is not domestic." "We call it a tavern because beer is by far the most common drink, even more than water, for the Sumerians", she said, noting that in one of the temples excavated in the area "there was a beer recipe that was found on a cuneiform tablet."

Uruk Plate Near the oven, archaeologist found a series of walls, benches and a set of shelves, Pittman said. The Miami Herald reported: The collapsed shelves used to have four levels — all loaded with bowls of food. Across the room, they found a structure made of a large pot and layers of pottery shards, Pittman said. Photos show the half-buried, circular structure. Pittman identified it as a “zeer,” an underground cooling device used like a refrigerator to keep foods and drinks cool.

The partially indoor, partially outdoor space would have served beer, bread, chicken and fish, Pittman said. Bones of both animals were unearthed with the bowls from the collapsed shelf.

The Great Lakes Brewing Company in Cleveland has produced a beer based on a 5,000-year-old Sumerian poem praising Ninkasi, the goddess of beer. Archaeology magazine reported: With guidance from Sumerologists and archaeologists, the brewers are using replica clay pots, as well as attempting to reproduce the yeast and barley bread cakes used in the brewing process. So far, their attempts have been dominated by a harsh sourness, so the experiment continues. [Source: Samir S. Patel Archaeology magazine, September-October 2013]

Sumerian Language

The Sumerian language died out long ago and does not belong to any known language family. It is not related to Akkadian, a contemporary language spoken by the Akkadians, which was a Semitic language. Assyriologist Ingo Schrakamp of the Free University of Berlin told Archaeology magazine: “Sumerian doesn’t have a modern relative, which means we can’t trace the etymology of words and we have no lexicon for it yet.” [Source: Kate Ravilious, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2022]

John Alan Halloran of sumerian.org wrote: “There appears to be some slight relation between Sumerian and both Ural-Altaic and Indo-European. This may just be due to having evolved in the same northeast Fertile Crescent linguistic area. I don't see any connection at all between Sumerian and Semitic. [Source: John Alan Halloran, sumerian.org]

Many cuneiform tablets are written in Akkadian. “Speakers of the Sumerian language coexisted for a thousand years with speakers of 3rd millennium Akkadian dialects, so the languages had some effect on each other, but they work completely differently. With Sumerian, you have an unchanging verbal root to which you add anywhere from one to eight prefixes, infixes, and suffixes to make a verbal chain. Akkadian is like other Semitic languages in having a root of three consonants and then inflecting or conjugating that root with different vowels or prefixes.”

On different Sumerian dialects, “There is the EME-SAL dialect, or women's dialect, which has some vocabulary that is different from the standard EME-GIR dialect. Thomsen includes a list of Emesal vocabulary in her Sumerian Language book. The published version of my Sumerian Lexicon will include all the variant Emesal dialect words. Emesal texts have a tendency to spell words phonetically, which suggests that the authors of these compositions were farther from the professional scribal schools. A similar tendency to spell words phonetically occurs outside the Sumerian heartland. Most Emesal texts are from the later part of the Old Babylonian period. The cultic songs that were written in Emesal happen to be the only Sumerian literary genre that continued to be written after the Old Babylonian period.”

Language and Writing at the Time of the Sumerians

Inscriptions from Ur

In addition to the Sumerians, who have no known linguistic relatives, the Ancient Near East was the home of the Semitic family of languages. The Semitic Family includes dead languages such as Akkadian, Amoritic, Old Babylonian, Canaanite, Assyrian, and Aramaic; as well as modern Hebrew and Arabic. The language of ancient Egypt may prove to be Semitic; or, it may be a member of a super-family to which the Semitic family also belonged. [Source: Internet Archive, from UNT]

There were also "The Old Ones," whose languages are unknown to us. Some presume their speech ancestral to modern Kurdish, and Russian Georgian, and call them Caucasian. Let's call these peoples Subartu, a name given to them after they were driven northward by the Sumerians and other conquerors of Mesopotamia.

Indo-Europeans spoke languages ancestral to all modern European languages except Finnish, Hungarian, and Basque. It was also ancestral to modern Iranian, Afghan, and most of the languages of Pakistan and India. They were not native to the Near East, but their intrusions into the area made them increasingly important after 2500 B.C.. F.

Though writing is still presumed to have evolved in Mesopotamia, it seems likely that the pre-Sumerian inhabitants of the valley, and not the Sumerians themselves, were the first to use it there. New evidence from Egypt re-opens the possibility that Egyptians may have started writing as early as the Mesopotamians. By 2400 B.C. writing was in use throughout the Near East from Harappan India westward, possibly as far as the Mediterranean island of Crete. Do not interpret this to mean that everyone within the described area knew how to read and/or write. To the contrary, the vast majority of the peoples who lived before A.D. 1900 never learned reading and writing. Because literacy was so narrowly confined to a small elite of lords and scribes, it was easy for entire civilizations to lose literacy. Such a loss was experienced by India from about 1700 B.C. to 1000 B.C., and by the peoples of Turkey and the Aegean area from 1200 to 800 B.C..

Sumerian Writing

Samuel Noah Kramer (1897–1990) was one of the world's leading Assyriologists and an expert in Sumerian history and Sumerian language. He wrote: Sumer's most significant contribution to civilization was the development of the cuneiform system of writing into an effective tool of communication. It began about 3000 B.C. as a crude pictographic script used for simple administrative memoranda, in which the signs represented ideograms or logograms; it ended up a thousand years later as a flexible phonetic syllabary adaptable to every kind of writing: legal, historical, epistolary, and literary. [Source: Samuel Noah Kramer, Encyclopaedia Judaica, Encyclopedia.com]

To teach and disseminate it, schools were established throughout the land, and thus formal education came into being. For purposes of instruction, the schoolmen developed a curriculum consisting of copying and memorizing especially prepared "textbooks" inscribed with long lists of words and phrases that covered every field of knowledge available to them: linguistic, botanical, zoological, geographical, mineralogical, and artifactual. An important part of the curriculum was mathematics, since no scribe could function as a competent secretary, accountant, or administrator without a thorough knowledge of the sexagesimal system of notation current throughout the land; the students had to copy, study, and memorize scores of tablets involving all sorts of mathematical operations, as well as numerous problem texts involving their practical application.

First Sumerian Writing

Akkadian language cuneiform

The Sumerian are credited with inventing writing around 3200 B.C. based on symbols that showed up perhaps around 8,000 B.C. What distinguished their markings from pictograms is that they were symbols representing sounds and abstract concepts instead of images. No one knows who the genius was who came up with this idea. The exact date of early Sumerian writing is difficult to ascertain because the methods of dating tablets, pots and bricks on which the oldest tablets with writing were found are not reliable.

By around 3200 B.C., the Sumerians had developed an elaborate system of pictograph symbols with over 2,000 different signs. A cow, for example, was represented with a stylized picture of a cow. But sometimes it was accompanied by other symbols. A cow symbols with three dots, for example, meant three cows.

By around 3100 B.C., these pictographs began representing sounds and abstract concepts. A stylized arrow, for example, was used to represent the word "ti" (arrow) as well as the sound "ti," which would have been difficult to depict otherwise. This meant individual signs could represent both words and syllables within a word.

The first clay tablets with Sumerian writing were found in the ruins of the ancient city of Uruk. It is no known what the said. They appear to have been list of rations of foods. The shapes appear to have been based on objects they represent but there is no effort to be naturalistic portrayals The marks are simple diagrams. So far over a half a million tablets and writing boards with cuneiform writing have been discovered.

Cuneiform writing remained the dominant form of writing in Mesopotamia for 3,000 years when it was replaced by the Aramaic alphabet. It began mainly as a means of keeping records but developed into a full blown written language that produced great works of literature such as the Gilgamesh story.

Sumerian Religion

Samuel Noah Kramer has argued that the Sumerians may have invented religion by building huge temples called ziggurats in their cities and establishing priestly castes devoted to the ritual worship of specific deities, Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science:

Which god was the mightiest in the vast Sumerian pantheon depended on the place and time: the sky god Anu, for example, was popular in early Uruk, while the storm god Enlil was worshiped in Sumer. Inanna — the "Queen of Heaven" — may have originally been a fertility goddess in Uruk; her worship spread to other Mesopotamian cities, where she was known as Ishtar, and may have influenced the goddesses of later civilizations, such as Astarte among the Hittites and the Greek Aphrodite.

A story very like that of the Hebrew Bible's Noah, who built an ark stocked with animals to preserve his family during a great flood caused by divine wrath, is related in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Archaeologists think it was originally a Sumerian story from about 2150 B.C. — centuries before the Hebrew version was written. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, September 12, 2022]

Samuel Noah Kramer wrote: The Sumerians believed that the universe and everything in it were created by four deities: the heaven-god An, the air-god Enlil, the water-god Enki, and the mother-goddess Ninhursag. To help them operate the universe effectively, these four deities, with Enlil as their leader, gave birth to, or "fashioned," a large number of lesser gods and goddesses, and placed them in charge of its various components and elements. All the gods were anthropomorphic and functioned in accordance with duly prescribed laws and regulations; though originally immortal, they suffered death if they over-stepped their bounds. [Source: Samuel Noah Kramer, Encyclopaedia Judaica, Encyclopedia.com]

Man was created for the sole purpose of serving the gods and supplying them with food and shelter, hence the building of temples and the offering of sacrifices were man's prime duties. Sumerian religion, therefore, was dominated by priest-conducted rites and rituals; the most important of these was the New Year sacred marriage rite celebrating the mating of the king with the goddess of love and procreation. Ethically, the Sumerians cherished all the generally accepted virtues. But sin and evil, suffering, and misfortune were, they believed, also divinely planned and inevitable; hence each family had its personal god to intercede for them in time of misfortune and need. Worst of all, death and descent to the dark, dreary netherworld were man's ultimate lot, and life on earth was therefore man's most treasured possession.

Sumerian Society

Samuel Noah Kramer wrote: Sumerian society was predominantly urban in character; large and small cities dotted the landscape and shaped its social, political, and economic life. Physically the city was rather drab and unattractive. Streets were narrow, crooked, and winding; they were unpaved, uncleaned, and unsanitary. Houses were thick-walled mudbrick compounds of several rooms, with here and there a more elegant two-story home. But the city had its broad boulevards, busy bazaar, and tempting public square. Above all, there was the sacred precinct with its monumental temple and sky-reaching ziggurat. The citizen took great pride in his city and loved it dearly, as is manifest from the heart-breaking laments in which the poets bewailed its destruction. [Source: Samuel Noah Kramer, Encyclopaedia Judaica, Encyclopedia.com]

The population of the city, which may have varied from 10,000 to 50,000, consisted of free citizens, serf-like clients, and foreign and native slaves. Some of the free citizens were high temple functionaries, important palace officials, and rich landowners; together these formed a kind of noble class. The majority of free citizens were farmers and fishermen, artisans and craftsmen, merchants and scribes. The serf-like clients were dependents of the temple, palace, and rich estates; they were usually given small plots of land for temporary possession, as well as rations of food and wool. Slaves were the property of their owners, but had certain legal rights: they could borrow money, engage in business, and buy their freedom.

The basic unit of society was the family. Marriage was arranged by the parents, and the betrothal, often accompanied by a written contract, was legally recognized as soon as the groom presented a bridal gift to the bride's father. Women had high legal standing: they could hold property, engage in business, and qualify as witnesses. But the husband could divorce his wife on relatively slight grounds and could marry a second wife if the first was childless. Children were under the absolute authority of the parents and could be disinherited or even sold into slavery.

Politically, the cities were governed by a viceroy who was subject to the king. Kingship was hereditary, but usurpers were frequent, and capitals changed from time to time. The king's word and authority were supreme, but he was not an arbitrary despot; as intermediary between the people and their gods, it was his responsibility to insure the prosperity and well-being of the land by leadership in war, the upkeep of the irrigation system, the building and restoration of the temples and their ziggurats, and the preservation and promotion of law and justice. There were also city assemblies of free citizens which originally wielded considerable power, but later became consultative bodies.

Sumerian Culture

The great Mesopotamia poem the Epic of Gilgamesh, in which a king seeks immortality from a man who spared mankind from a deadly deluge with a giant boat, first appeared with the Sumerians and perhaps goes back even firther. This flood story is believed to be the source of the Biblical story of Noah. [Source: Craig Simpson, The Telegraph, November 18, 2023]

In the period before 2700 B.C., the Sumerians considered most of their kings to be gods, or at least heros. The Deification and Heroization of kings mostly ceased after Gilgamesh, king of Uruk around 2700 B.C.. The Gilgamesh of the epic was predominantly an Heroic, but tragic, figure. He was no god. Some early Sumerian tales about Gilgamesh make him appear ambivalent. He was not a great king. The story, "Gilgamesh and Agga of Kish," shows him forced to acknowledge the overlordship of the Great King of Kish, possibly Mesannepada of Ur.

Marcos Such-Gutiérrez wrote in National Geographic History: During the Akkadian control of Sumer, Akkadian was the preferred language but it was written in Sumerian cuneiform. This choice helped preserve Sumerian literary texts. Many of them were preserved in copies from the later Old Babylonian period (2003-1595 B.C.). Sumerian literature included hymns, magic spells, morality texts, and myths about the gods. [Source: Marcos Such-Gutiérrez, National Geographic History, August 25, 2023]

Early poems in Sumerian about a king of Uruk called Gilgamesh were later woven into an epic tale, a version of which was found in Nineveh in the 19th century. Gilgamesh’s quest for immortality has entered the canon of classic literature and been translated into numerous languages across the world. It is hailed as one of the world’s earliest heroic epics.

Five poems written in Sumerian in the early second millennium B.C. centered on the adventures and accomplishments of a legendary king of Uruk, Gilgamesh. As Sumerian literature infused Akkadian culture, Gilgamesh’s exploits, such as fighting the monster Huwawa, were fused into a single epic written in Akkadian. The Epic of Gilgamesh follows the king’s quest for immortality. The text was discovered in the library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal, who ruled in the seventh century B.C. Unearthed in the mid-1800s, the tablets were taken to the British Museum, where, in 1872, the Assyriologist George Smith deciphered the lines that describe a Great Flood similar to the one in the Old Testament.

The Sumerians were fascinated by wild creatures. Sumerian artworks expertly rendered fierce lions while The Epic of Gilgamesh contrasts civilized Gilgamesh with his friend Enkidu, a wild man who “fed with the gazelles on grass, and drank with the wild animals.” But the Sumerians’ myth also revered the goat, one of humanity’s first domesticated animals. Goat milk appears as a source of divine nourishment, such as the god Ningirsu whose mother was a goat. Goats were also associated with Enki, a Sumerian god of water, creation, and fertility who is sometimes depicted as part goat. Stone reliefs depict Enki’s followers bearing goats to his temple as offerings. Even Sumerian figures of speech attributed wisdom to goats, like the inscription, “Although it has never gone there, the goat knows the wasteland.”

Sumerian Art

ram in a thicket The Sumerians created lovely alabaster vases with carved heads, alabaster and stone figurines, cylinder seals made with precious stones, gold ornaments, gold jewelry and musical instruments decorated with gold and semi-precious stones. The were expert metal workers adept at fashioning silver and gold. An inlaid gold vessel in the form of an ostrich egg might have held food and drink.

Most of the Sumerian works of art have been excavated from graves. The Sumerians often buried their dead with their most prized objects. They also produced some of the first portraits. Gudea, the Sumerian king of Lagash, who lived around 2100 B.C., is remembered with a series of seated sculptures that are among the most famous Sumerian works of art. A life size one made of black diorite is particularly nice.

Much of the stuff found by Sir Leonard Woolley’s excavations at Ur is now in the British Museum. Some is at the Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. One of the most famous objects there is Great Lyre from the King’s Grave. It is a gold-and-lapis-lazuli bull’s head and inlaid shell plaque attached to a re-created wooden frame.

The soundbox of a lyre unearthed in a grave in Ur, dated at 2700 B.C., contains an amusing comic-book-like rendering of animals made with a mosaics of shell, gold, and silver on a background of lapis lazuli. The image is believed to a depiction of a poplar fable. A finely carved gypsum head of an unknown subject, dated 2097 to 1989 B.C., features eery eyes colored with blue pigments.

See Separate Article: SUMERIAN ART AND TREASURES FROM THE TOMBS OF UR africame.factsanddetails.com

Sumerian Medicine and Legal Code

Marcos Such-Gutiérrez wrote in National Geographic History: The Sumerians’ rich written record also preserved evidence of medical advances , including the first prescriptions in history. These texts include a description of the ailment and a suggested remedy. References to poultices, potions, and dousing appear in Sumerian texts. Although it has been difficult to identify the ailments with any known conditions, these records suggest that Sumerian pharmacology was advanced. They show knowledge of sophisticated methods for obtaining substances such as powdered alkali, potassium nitrate, and saltpeter for use in their remedies. [Source: Marcos Such-Gutiérrez, National Geographic History, August 25, 2023]

The world’s first ever legal code, created by the Sumerian king Ur-Nammu between 2100 and 2050 B.C. he reconstructed text, based on fragmentary copies found in the 20th century A.D.,begins with an account of how Ur-Nammu established justice, reforming the system of weights and measures and ensuring that orphans and widows were not prey to the powerful. Ur-Nammu’s code influenced later Mesopotamian legal systems, most notably the Code of Hammurabi, the Babylonian king who reigned three centuries later.

Sumerian Economy

Organized production of handcrafted good was first developed in Mesopotamia. The Sumerians produced manufactured goods. The weaving of wool by thousands of workers is regarded as the for large-scale industry.

The Sumerians a developed sense of ownership and private property. It seems like many business transactions were recorded and the minutest amounts and smallest quantities were listed. Contracts were sealed with cylinder seals that were rolled over clay to produce a relief image. There wasn't much in Ur and other cities in Mesopotamia except water from the Euphrates River and mud brick made from the dry earth. Prized materials such as gold, silver, lapis lazuli, agate, carnelian all were imported.

The Sumerians established trade links with cultures in Anatolia, Syria, Persia and the Indus Valley. Similarities between pottery in Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley indicate that trade probably occurred between the two regions. During the reign of the pharaoh Pepi I (2332 to 2283 B.C.) Egypt traded with Mesopotamian cities as far north as Ebla in Syria near the border of present-day Turkey.

The Sumerians traded for gold and silver from Indus Valley, Egypt, Nubia and Turkey; ivory from Africa and the Indus Valley; agate, carnelian, wood from Iran; obsidian and copper from Turkey; diorite, silver and copper from Oman and coast of Arabian Sea; carved beads from the Indus valley; translucent stone from Oran and Turkmenistan; seashell from the Gulf of Oman. Raw blocks of lapis lazuli are thought to have been brought from Afghanistan by donkey and on foot. Tin may have come from as far away as Malaysia but most likely came from Turkey or Europe.

Sumer’s Writing and Economy Grew Hand in Hand

Marcos Such-Gutiérrez wrote in National Geographic History: Sumer’s agricultural successes led to a need for a methodical system of recording information. Sumerian merchants needed reliable ways to track their businesses. Somewhere around 3500 B.C., merchants began using soft clay tablets impressed with small symbols to keep track of their goods. These pictorial symbols evolved by 3200 B.C. into a complex series of signs of about 600 characters known as Sumerian script. Writing had been born. [Source: Marcos Such-Gutiérrez, National Geographic History, August 25, 2023]

Resembling little wedges and lines, Sumerian writing was created by pressing a reed into wet clay tablets. This technique gave the system its modern name of cuneiform, from the Latin word for wedge. Sumerian script sparked a revolution. Other language groups found across Mesopotamia adopted it. Cuneiform tablets have been found in multiple Sumerian archaeological sites.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: ““Simple pictographs were drawn on clay tablets to record the management of goods and the allocation of workers' rations. These pictographs are the precursors of later cuneiform writing. Until around 3000 B.C., objects inspired by Mesopotamia were found from central Iran to the Egyptian Nile Delta. However, this widespread culture collapsed and Mesopotamia looked inward for the next few centuries. Yet cities such as Uruk continued to expand. \^/ [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "Uruk: The First City", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003 \^/]

“During the following Early Dynastic period (2900–2350 B.C.), when city-states dominated Mesopotamia, the city rulers gradually grew in importance and increasingly sought luxury materials to express their power. These goods, often from abroad, were acquired either by trade or conquest. At this time Uruk was surrounded by a massive wall, which according to tradition was built on the orders of King Gilgamesh. Although he may have been an actual king of Uruk around 2700 B.C., Gilgamesh became the hero of many later stories and epics.” \^/

Commerce was one way cuneiform spread, but scholars believe that conquest was another. Sumerian cities conquering each other expedited cultural exchanges. For instance, Eannatum of Lagash brought not only much of Sumer under his control in around 2500 B.C. but also areas of Elam to the east. Ironically, however, the durability of Sumerian literary culture and the use of the cuneiform system—which later spread throughout the Near East and remained in use until as late as A.D. 75—owes less to Sumer conquering than its being conquered.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except irrigation picture from Michigan State University

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, Archaeology magazine, Live Science, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024