Home | Category: Sumerians and Akkadians / Religion

NIPPUR

Reconstruction on the ruins of a Nippur temple

Nippur (pronounced ‘nĭ poor’) was a major religious center of Mesopotamia. Established by the pre-Mesopotamian“Ubaid” people around 4,500 B.C., Nippur was seat of the cult of Enlil, one of the most important Mesopotamian gods. It was never an important city-state and was ruled by other city-states. It is possible, but improbable, that Nippur was the "Calneh" mentioned in Genesis 10 of the Old Testament. Nippur is located 160 kilometers south of Baghdad, 100 kilometers east of present-day Najaf, and 80 kilometers southeast of Babylon on the canal Sha al-Nil, which was at one time, perhaps when Nippur was founded, was a separate branch of the Euphrates River.

According to the Oriental Institute ofThe University of Chicago: “In the desert a hundred miles south of Baghdad, Iraq, lies a great mound of man-made debris sixty feet high and almost a mile across. This is Nippur, for thousands of years the religious center of Mesopotamia, where Enlil, the supreme god of the Sumerian pantheon, created mankind. Although never a capital city, Nippur had great political importance because royal rule over Mesopotamia was not considered legitimate without recognition in its temples. Thus, Nippur was the focus of pilgrimage and building programs by dozens of kings including Hammurabi of Babylon and Ashurbanipal of Assyria. Despite the history of wars between various parts of Mesopotamia, the religious nature of Nippur prevented it from suffering most of the destructions that befell sites like Ur, Nineveh, and Babylon. The site thus preserves an unparalleled archaeological record spanning more than 6000 years. [Source: Oriental Institute of The University of Chicago ^^]

“Objects can often tell us things that were not written down. Elaborately designed items made of precious metals, stones, exotic woods, and shell allow us to reconstruct the development of ancient Mesopotamian art, as well as the far-flung trading connections that brought the materials to Babylonia. Egyptian, Persian, Indus Valley, and Greek artifacts also found their way to Nippur. Even after Babylonian civilization was absorbed into larger empires, such as Alexander the Great's, Nippur flourished. In its final phase, prior to its abandonment around A.D. 800, Nippur was a typical Muslim city, with minority communities of Jews and Christians. At the time of its abandonment, the city was the seat of a Christian bishop, so it was still a religious center, long after Enlil had been forgotten.” ^^

Excavations were conducted in Nippur by American expeditions, mainly by the University of Pennsylvania, in 1890, 1893-1896, 1899-1900, 1948 and every other year after that through 1958. These excavations revealed parts of the Ekur “Mountain House,” the temple of Enlil and Sumer’s leading shrine, the temple of Enlil’s consort, Ninlil, a large temple dedicated to the goddess Inanna, and a small temple dedicated to an unknown deity, as well as houses of the scribal quarter of the city. More recently research and excavations have been overseen by the Oriental Institute of The University of Chicago.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SUMERIANS: SUMER, HISTORY, ORIGINS, IRRIGATION africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN RULERS, GOVERNMENT, WARFARE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN LIFE, CULTURE AND LANGUAGE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN RELIGION: CITY-STATE GODS, TEMPLES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN ART AND TREASURES FROM THE TOMBS OF UR africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN CITY STATES AND CITIES: URUK, LAGASH AND GIRSU africame.factsanddetails.com ;

UR: THE GREAT CITY OF SUMER AND HOMETOWN OF ABRAHAM africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DECLINE OF THE SUMERIANS AND THEIR FALL TO THE AKKADIANS AND ELAMITES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

AKKADIANS: EMPIRE, SARGON. LANGUAGE, CULTURE africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“Temples of Enterprise: Creating Economic Order in the Bronze Age Near East”

by Michael Hudson (2024) Amazon.com;

“Nippur V: The Area WF Sounding: The Early Dynastic to Akkadian Transition (Oriental Institute Publications) by Augusta McMahon , McGuire Gibson, et al. (2006) Amazon.com;

“Nippur IV: The Early Neo-Babylonian Governor's Archive from Nippur (Oriental Institute Publications) by Steven W. Cole (1996) Amazon.com;

“The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion” by Thorkild Jacobsen (1976) Amazon.com;

“The Temple of Ningirsu: The Culture of the Sacred in Mesopotamia” by Sébastien Rey (2024) Amazon.com;

“Sumerian Hymns and Prayers to God Nin-Ib: From the Temple Library at Nippur”

by Hugo Radau (2022) Amazon.com;

“For the Gods of Girsu: City-State Formation in Ancient Sumer” by Sébastien Rey (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character” by Samuel Noah Kramer (1971) Amazon.com;

“Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization” by Paul Kriwaczek (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“A Handbook of Ancient Religions” by John R. Hinnells (2007) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary” by Jeremy Black (1992) Amazon.com;

“The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture” by Francesca Rochberg Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography” by Wayne Horowitz (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Social World of the Babylonian Priest” by Bastian Still (2019) Amazon.com;

History of Nippur

Nippur wasn’t a great a Sumerian city like Uruk or Ur but it thrived in the Sumerian era as it did in Babylonian and Assyrian times. According to the Oriental Institute ofThe University of Chicago: “ Settled around 5000 B.C., Nippur played an important role in the development of the world's earliest civilization. The city, with its many temples, government buildings, and important family businesses, was probably more literate than other towns, and the scribes have left thousands of Sumerian and Akkadian documents written on clay tablets. Included among this extraordinary body of texts are the oldest versions of literary works, such as the Gilgamesh Epic and the Creation Story, as well as administrative, legal, medical and business records, and school texts. [Source: Oriental Institute ofThe University of Chicago]

According to Biblegate: “Although the city wielded no political power, it was the undisputed religious and cultural center from the early third millennium until the days of Hammurabi. From the 17th cent. until the 14th, datable material ceases. By the time of Hammurabi, Nippur had yielded to Babylon as a religious and cultural center, but it continued to be an important city down to Parthian times. [Source: biblegateway.com, H. W. Hilprecht, “The Excavations in Assyria and Babylonia” (1904), 289-577; C. S. Fisher, Excavations at Nippur (1907); V. C. Crawford, “Nippur the Holy City” Archaeology 12 (1959), 74-83]

J. Frederic McCurdy wrote in the Jewish Encyclopedia: “The reconstructed history of Babylonia, which begins about 4500 B.C., shows at its earliest stages that Nippur was even then a city of ancient religious renown. The kings of other city-states, such as Kish, Erech, and Ur, vied with one another in the endeavor to secure the patronage of the city of Bel. Later, about 3800, the famous Sargon of Accad presented votive offerings at the shrine of Bel and rebuilt his chief temple. [Source: J. Frederic McCurdy, jewishencyclopedia.com; Peters, Nippur or Explorations and Adventures on the Euphrates, 1897; Hilprecht, Explorations in Bible Lands, 1903, pp. 289-568.]

“The same story is repeated in varying forms down to the very end of Babylonian history. Khammurabi (2250 B.C.), who unified Babylonia and organized it throughout, wishing to gain for his capital the prestige of Bel-worship, discouraged the cult of that deity at Nippur and transferred it as far as possible to the city of Babylon. There the worship of Bel was united with that of Marduk of Babylon, who actually assumed the name of the patron god of Nippur (comp. Isa. xlvi. 1). The fiction was maintained down to the days of the great Nebuchadrezzar (604-562), who found it necessary to demolish by force the restored temple of Bel at Nippur for the aggrandizement of "Babylon the Great." [Ibid]

Religion in Nippur

deities Enlil and Ninlil

Built on the Euphrates and at its height around 2500 B.C., Nippur was the home of important temple dedicated to Enlil, a storm god sometimes treated like supreme deity, and other temples, including one dedicated to Bau (Gula), the Mesopotamian goddess of healing.

A large archive of Sumerian cuneiform records was found in Nippur. Even after the city was past its prime Sumerian pilgrims visited temples honoring Enlil. A famous limestone statuette found at the Inanna Temple in Nippur depicts a woman with her hands clasped in worship. The world oldest known prescriptions, cuneiform tablets dating back to 2000 B.C. from Nippur, described how to make poultices, salves and washes. The ingredients, which included mustard, fig, myrrh, bat dropping, turtle shell powder, river silt, snakeskins and "hair from the stomach of a cow," were dissolved into wine, milk and beer.

According to Biblegate: “Nippur was the seat of the cult of Enlil, and the ancient renown of this god insured his city the continued care on the part of the Babylonian kings. As late as the 7th cent. B.C., the Assyrian king, Ashurbanipal, restored Enlil’s temple. Nippur was the seat of Sumer’s most important “academy” and in the lit. composed and redacted in this academy, Nippur and its leading deities, Enlil, his wife Ninlil, and his son Ninurta, played a large role. Excavators found some 30-40,000 tablets and fragments at Nippur, and about 4,000 of these are inscribed with Sumer. works.

J. Frederic McCurdy wrote in the Jewish Encyclopedia: Nippur’s “ancient renown was due partly to its central position among the Semitic settlements, and especially to the fact that it was the first known great seat of the worship of Bel. The name of this chief Babylonian god, identical with the Canaanitish Ba'al, suggests that his worship at Nippur was the consolidation of that of many local Ba'als, and that Nippur obtained its religious preeminence by having gained the leadership among the Semitic communities. In any case its predominance was actually established at least as early as 5000 B.C. [Source: J. Frederic McCurdy, jewishencyclopedia.com; Peters, Nippur or Explorations and Adventures on the Euphrates, 1897; Hilprecht, Explorations in Bible Lands, 1903, pp. 289-568.

Enlil and Nippur

Morris Jastrow said: “We have seen that the city of Nippur occupied a special place among the older centres of the Euphrates Valley, marked not by any special political predominance—though this may once have been the case—but by a striking religious significance. Corresponding to this position of the city, we find the chief deity of the place, even in the oldest period, occupying a commanding place in the pantheon and retaining a theoretical leadership even after Enlil was forced to yield his prerogatives to Marduk. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

Inscription from Ekur, an Enlil temple

“The name Enlil is composed of two Sumerian elements and signifies the “lord of the storm.” His character as a storm-god, thus revealed in his name, is further illustrated by traits ascribed to him. The storm constitutes his weapon. He is frequently described and addressed as the “Great Mountain.” His temple at Nippur is known as E-Kur, “Mountain House,” which term, because of the supreme importance of this Temple, became, as we have seen,the general name for a sanctuary. Since, moreover, his consort Ninlil is designated as Nin-Kharsag, “Lady of the Mountain,” there are substantial reasons for assuming that his original seat was on the top of some mountain, as is so generally the case with storm-deities like Jahweh, the god of the Hebrews, the Hittite god Teshup, Zeus, and others. There being no mountains in the Euphrates Valley, the further conclusion is warranted that Enlil was the god of a people whose home was in a mountainous region, and who brought their god with them when they came to the Euphrates Valley, just as the Hebrews carried the cult of Jahweh with them when they passed from Mt. Sinai into Palestine.

“Nippur is so essentially a Sumerian settlement that we must perforce associate the earliest cult of Enlil with the non-Semitic element in the population. Almost the only region from which the Sumerians could have come was the east or the north-east—the district which in a general way we may designate by the name Elam, though the Sumerians, like the Kassites in later days, might have originated in a region considerably to the north of Elam. While, as has been pointed out, it is not ordinarily possible to separate the Sumero-Akkadian civilisation into its component parts—Semitic and non-Semitic—and more particularly in reference to gods, beliefs, and rites is any detailed attempt to exactly differentiate between the additions made by one group or another destined to failure, yet in some instances it is possible to do so.

Nippur’s Role in Mesopotamia

Morris Jastrow said: “The prominent influence exerted by religion in the oldest period finds a specially striking illustration in the position acquired by the city of Nippur—certainly one of the oldest centres in the Euphrates Valley. So far as indications go, Nippur never assumed any great political importance, though it is possible that it did so at a period still beyond our ken. But although we do not learn of any jurisdiction exercised by her rulers over any considerable portion of the Euphrates Valley, we find potentates from various parts of Babylonia and subsequently also the Assyrian kings paying homage to the chief deity of the place, Enlil. To his temple, known as E-Kur, “mountain house,” they brought votive objects inscribed with their names. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

foundation nail from Nippur

“Rulers of Kish, Uruk, Ur, Lagash, Agade are thus represented in the older period, and it would appear to have been almost an official obligation for those who claimed sovereignty over the Euphrates Valley to mark their control by some form of homage to Enlil, the name of whose temple became in the course of time a general term for “sanctuary.” The patron deities of other centres, such as Ningirsu of Lagash, Nergal of Cuthah, Sin of Ur, Shamash of Sippar, and Marduk of Babylon, were represented by shrines or temples within the sacred quarter of Nippur; and the rulers of these centres rarely failed to include in their titles some reference to their relationship to Enlil and to his consort Ninlil, or, as she was also called, Nin-Kharsag, “the lady of the mountain.”

“The position thus occupied by Nippur was not unlike that of the sacred places of India like Benares, or like that of Rome as the spiritual centre of Christendom during the Middle Ages. Sumerians and Semites alike paid their obeisance to Enlil, who through all the political changes retained, as we shall see, the theoretical headship of the pantheon. When he is practically replaced by Marduk, the chief god of the city of Babylon, after Babylon had become the political centre of the entire district, he transfers his attributes to his successor. As the highest homage paid to Marduk, he is called the bel or “lord” par excellence in place of Enlil, while Marduk’s consort becomes Ninlil, like the consort of Enlil.

“The control of Nippur was thus the ambition of all rulers from the earliest to the latest periods; and the plausible suggestion has been recently made that the claim of divinity, so far as it existed in ancient Babylonia, was merely intended as an expression of such control—an indication that a ruler who had secured the approval of Enlil might regard himself as the legitimate vicegerent of the god on earth, and therefore as partaking of the divine character of Enlil himself.”

Holy City of Nippur

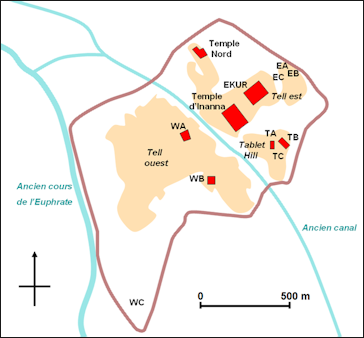

McGuire Gibson of The University of Chicago wrote: “From earliest recorded times, Nippur was a sacred city, not a political capital. It was this holy character which allowed Nippur to survive numerous wars and the fall of dynasties that brought destruction to other cities. Although not a capital, the city had an important role to play in politics. Kings, on ascending the throne in cities such as Kish, Ur, and Isin, sought recognition at Ekur, the temple of Enlil, the chief god of the Mesopotamian pantheon (Fig. 3). In exchange for such legitimization the kings lavished gifts of land, precious metals and stones, and other commodities on the temples and on the city as a whole. At the end of successful wars, rulers would present booty, including captives, to Enlil and the other gods at Nippur. Most important, kings carried out for the city elaborate construction and restoration of temples, public administrative buildings, fortification walls, and canals. Even after 1800 B. C., when the Babylonians made Marduk the most important god in southern Mesopotamia, Enlil was still revered, kings continued to seek legitimization at Nippur, and the city remained the recipient of pious donations. The city underwent periodic declines in importance [Gibson 1992) but rose again because its function as a holy center was still needed. The greatest growth of the city (Fig. 2), which occurred under the Ur III kings (c. 2100 B.C), was almost matched in the time of the Kassites (c. 1250 B.C.) and in the period when the Assyrians, from northern Iraq, dominated Babylonia (c. 750-612 B.C.). [Source: McGuire Gibson, Professor of Mesopotamian Archaeology, The Oriental Institute The University of Chicago, Al-Rafidan, Vol. XIV, 1993 /*/]

layout of Nippur temple

“The strength of Mesopotamian religious tradition, which gave Nippur its longevity, can be illustrated best by evidence from the excavation of the temple of Inanna, goddess of love and war. Beginning at least as early as the Jemdet Nasr Period (c. 3200 B.C.), the temple continued to flourish as late as the Parthian Period (c. A.D. 100), long after Babylonia had ceased to exist as an independent state and had been incorporated into larger cultures with different religious systems (Persian, Seleucid, and Parthian empires). The choice of Nippur as the seat of one of the few early Christian bishops, lasting until the city's final abandonment around A.D. 800, was probably an echo of its place at the center of Mesopotamian religion. In the Sasanian Period, 4th to 7th Centuries, A.D., most of the major features of Mesopotamian cultural tradition ceased, but certain aspects of Mesopotamian architectural techniques, craft manufacture, iconography, astrology, traditional medicine, and even some oral tradition survived, and can be traced even today not just in modern Iraq but in a much wider area. /*/

“The origins of Nippur's sacred character cannot be determined absolutely, but some suggestions can be made. The city's special role was derived, I would suggest, from its geographic position on an ethnic and linguistic frontier. To the south lay Sumer, to the north lay Akkad; the city was open to the people from both areas and probably functioned as an arbiter in disputes between these potential enemies. The existence of the frontier can be demonstrated from texts as early as the Early Dynastic III period (c. 2600 B.C.), when Sumer was the dominant cultural entity. In tablets from Shuruppak, a city 45 kilometers southeast of Nippur, more than 95% of the scribes had Sumerian names, while the rest had Akkadian names. In contrast, at Abu Salabikh, 12 kilometers to the northwest of Nippur, literary and other scholarly texts were written in equal numbers by Sumerian and Akkadian scribes [Biggs 1967]. But, Biggs notes that in the preparation of administrative texts at Abu Salabikh there was a greater representation of Sumerian scribe names, about 80%. This fact may indicate that although Akkadians were deeply involved in all aspects of life in the area just north of Nippur, government affairs may have remained predominantly the preserve of Sumerians in the pre-Sargonic period. For Nippur, we do not know as yet what percentage of scribes had Akkadian names in Early Dynastic III, but Biggs [1988] has suggested that the percentages at Nippur would be more like those of Shuruppak than like those of Abu Salabikh. I would suspect, however, that the percentages for non-governmental texts were closer to those at Abu Salabikh, with a good number of Akkadian scribes in evidence.” /*/

Nippur, a Thriving Economic Center

McGuire Gibson of The University of Chicago wrote: “As is the case with the world's other holy cities, such as Jerusalem, Mecca, and Rome, Nippur was a vibrant economic center. Besides the economic benefits derived from gifts and on-going maintenance presented by kings and rich individuals, there was probably a continuing income from pilgrims. Nippur was the center of an agricultural district, with much of the land in the possession of temples. The temples produced manufactured goods, predominantly textiles and finished items, some of which were meant for export. But the temples were only part of the economic picture [Maekawa 1987]. Even though it was more dominated by religion than other towns, Nippur, like them, had a mixed economy, with governmental, religious, and private spheres (see, e.g. Westenholz [1987]). Steadily accumulating evidence indicates that the public spheres were closely integrated, with final control in the hands of government officials (see esp. Maekawa [1987]).[Source: McGuire Gibson, Professor of Mesopotamian Archaeology, The Oriental Institute The University of Chicago, Al-Rafidan, Vol. XIV, 1993 /*/]

“The work-force for much of the large-scale manufacture was probably connected with the major institutions, especially the temples. As in most countries until modern times, the temples in Mesopotamia had an important function as social welfare agencies, including the taking in of widows and orphans who had no families or lineages to care for them [Gelb 1972]; temples also were the recipients of war prisoners, especially those from foreign lands, who worked in agricultural settlements belonging to temples or in other temple service [Gelb 1973]. Such dependent people probably worked for generations in the service of one temple as workers and soldiers (gurus/erin), rather than as slaves (sag) [Gelb 1973: 94-95]. /*/

Administration of Nippur and Its Temples

McGuire Gibson of The University of Chicago wrote: “All institutions, whether the governor's palace, a government-sponsored industry, or a temple, were not just buildings and not just abstract bureaucratic hierarchies or economic establishments, but were social organizations within a broader social network. As happens in most societies, large institutions in ancient Mesopotamia tended to be dominated by families, lineages, and even larger kinship groups and I would argue that it is this web of kinship that furnishes the long-term, underlying continuity for civilizations, making it possible to reassemble the pieces even after disastrous collapses. For Mesopotamia, the role and power of such kinship organizations is best observed ironically in the Ur III Period, the most centralized, bureaucratized period in Mesopotamian history. The abundance of records of administrative minutiae allows the reconstruction not just of the administrative framework, but of the social network underlying and imbedded within it. The best reconstruction of such a kin-based organization within an institution is Zettler's [1992] work on the Inanna temple. One branch of the Ur-me-me family acted as the administrators of the temple, while another dominated the governorship of Nippur and the administration of the temple of Enlil. [Source: McGuire Gibson, Professor of Mesopotamian Archaeology, The Oriental Institute The University of Chicago, Al-Rafidan, Vol. XIV, 1993 /*/]

Nippur temple excavtion in 1893

“It is important to note that the Ur-me-me family remained as adminstrators of the Inanna temple from some time within the Akkadian period to at least as late as the early years of the Isin dynasty. Thus, while dynasty replaced dynasty and the kingship of Sumer and Akkad shifted from city to city (Akkad to Ur to Isin) the family remained in charge of the Inanna temple. From the listing of members of two and three generations as minor figures on the temple rolls, it is clear that it was not just the Ur-me-me family that found long-term employment within the temple's economic and social skucture. Through the continued association of families with the institution, not only were generations of people guaranteed a livelihood, but the institution was guaranteed a cadre which would pass on the routines that made the institution function. The temple could add key personnel not only through a kind of birth-right (family or lineage inclusion), but also through recruitment; important individuals within the institution's adrninistration would have acted as patrons not just for nephews, nieces, and more distant relatives but also for unrelated persons. By incorporating clients of its important men and women, an institution could forge linkages with the general population in the city as well as in the supporting countryside and in other cities; these recruits, in taking up posts within a temple, a municipal establishment, the royal bureaucracy, or in a large family business, would ensure that the patron had loyal adherents./*/

“We know from cuneiform texts found at Nippur and elsewhere that the temples, rather than controlling the cities through a "Temple Economy," as was proposed earlier in this century, were under supervision by a king or a royally appointed governor, even in the Early Dynastic III period (c. 2600 B.C.) [Foster 1981; Maekawa 1987]. In the Akkadian period (c. 2300 B.C.), the temples of Inanna and Ninurta seem to have been under very close control of the governor, but the ziggurat complex, dedicated to Enlil, appears to have been more autonomous, reporting directly to the king in Agade [Westenholz 1987: 29]. During the Ur III period (c. 2100 B.C.) at Nippur, the administrator of the Inanna temple had to report to his cousin, the governor, on the financial affairs of the temple, and even had to go to the governor's storehouse to obtain the ritual equipment for specific feasts of the goddess [Zettler 1992]. The situation was much the same in the Isin-Larsa period, with texts from one agency (presumably the governor's office) recording distribution of goods to several temples; it is unfortunate that a recent article [Robertson 1992] revives, again, the notion of "temple economy" to cover these transactions. /*/

“The characteristics of administration and support that can be reconstructed from texts for a few temples at Nippur must be assumed to have been operative in the rest of Nippur's temples. The relationship of those temples to governmental institutions and to private entities and individuals is only beginning to be worked out. To reconstruct life in ancient cities one cannot rely on written documents alone, since they do not cover the entire range of ancient activity. Often, crucial insights can be obtained by the correlation of non-inscribed evidence, for instance the repeated co-occurrence of a set of artifacts in one type of find-spot. Especially valuable are correlations that illustrate human adaptations to natural environrnental conditions. When one can bring texts into such correlations, truly innovative syntheses can be made. Whenever possible, documents must be viewed in their archaeological contexts, treating them as an extraordinarily informative class of artifacts to be studied in relationship to all other items. When such relationships are studied, a much more detailed picture emerges. Although that procedure would appear to be self-evidently valuable, it is rare that texts have been treated in this manner. At Nippur, we have made a concerted effort to combine all kinds of information in our interpretations of the site, and we think that we have made some important discoveries by so doing.” /*/

Nippur temple excavation

Nippur Map Tablet

The Nippur Map Tablet is made of clay, dates to 1500 B.C. and measures 13 x 11 centimeters (5 x 4.3 inches). Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: For the busy farmers of the Babylonian sacred city of Nippur, ready access to water was essential. It’s hardly surprising, then, that this tablet, which maps an area near the city, features a complex irrigation network of ditches and canals, depicted by lines, along with a number of towns and agricultural estates, represented by circles. What is somewhat surprising, though, is that a map of the area was produced at all. Landholdings in Mesopotamia were typically described rather than drawn, explains Philip Jones, a curator at the Penn Museum. “It’s difficult to put your finger on why this map was created,” he says, “but it must have been for some administrative purpose.” [Source:Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2019]

“The map’s central section, identified in cuneiform writing as a “field of the palace,” suggests that the tablet served as a guide to estates belonging to the recently established Kassite Dynasty, which was based in the city of Babylon, around 70 miles northwest of Nippur. At this time, the region’s new Kassite rulers were challenging the religious establishment in Nippur, which had long been the seat of the chief Sumerian god, Enlil. The top center section of the tablet includes an estate and field of Marduk, the patron god of Babylon. Says Jones, “What we see here is that Marduk is beginning to usurp Enlil’s place and is actually getting land within Enlil’s own city.”

Lament for Nippur

The Lament for Nippur (Lament for Nibru) is a Sumerian lament dated to the Old Babylonian Empire (c. 1900–1600 BCE). Preserved in Penn Museum on tablet CBS13856, it is one of five known Mesopotamian "city laments"—dirges for ruined cities in the voice of the city's tutelary goddess.

It goes: After the cattle pen had been built for the foremost divine powers — how did it become a haunted place? When will it be restored? Where once the brick of fate had been laid — who scattered its divine powers? The lamentation is reprised: how did the storeroom of Nippur, the shrine Dur-an-ki, become a haunted place? When will it be restored? After Ki-ur, the sanctuary, had been built, after the brickwork of E-kur had been built, after Ubcu-unkena had been built, after the shrine Egal-mah had been built — how did they become haunted? When will they be restored? [Source: piney.com]

How did the true city become empty? Its precious designs have been defiled! How were the city's festivals neglected? Its magnificent rites have been thrown into disorder! In the heart of Nippur, where the divine powers were allotted and the black-headed people prolificly multiplied, the city's heart no longer revealed any sign of intelligence — there where the Anuna used to give advice! In Ubcu-unkena, the place for making great judgments, they no longer impart decisions or justice!

Where its gods had established their dwellings, where their daily rations were offered, their daises erected, where the sacred royal offering and the evening meal in their great banquet hall were destined for the pouring out of choice beer and syrup — Nippur, the city where the black-headed people used to cool themselves in its spreading shade — in their dwellings Enlil fell upon them as if they were criminals. It was he who sent them scattering, like a scattered herd of cattle. How long until its lady, the goddess Ninlil, would ask after the inner city, whose bitter tears were overwhelming?

As though it were empty wasteland, no one enters that great temple whose bustle of activity was famous. As for all the great rulers who increased the wealth of the city of Nippur — why did they disappear? For how long would Enlil neglect the Land, where the black-headed people ate rich grass like sheep? Tears, lamentation, depression and despair! How long would his spirit burn and his heart not be placated? Why were those who once played the cem and ala drums spending their time in bitter lamenting? Why were the lamenters sitting in its brick buildings? They were bewailing the hardship which beset them.

The men whose wives had fallen, whose children had fallen, were singing "Oh! Our destroyed city!". Their city gone, their homes abandoned — as those who were singing for the brick buildings of the good city, as the lamenters of wailing, like the foster-children of an ecstatic no longer knowing their own intelligence, the people were smitten, their minds thrown into disorder. The true temple wails bitterly.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see ETCSL project, Faculty of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018