Home | Category: Sumerians and Akkadians

SUMERIAN CITY-STATES

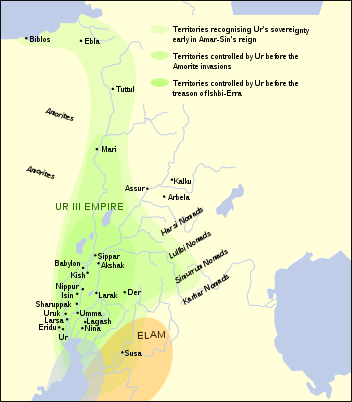

Map of Sumer in the Ur III period The Sumerians didn’t establish an empire like the Romans did. They lived in a bunch of independent city-states like the Greeks. The first cluster Mesopotamian settlements were established in ancient Sumer around 3,500 B.C. These settlement grew into the city states of Ur (home of Abraham and the Chaldees in the Bible), Eridu, Uruk (Biblical city of Erech), Lagash, Nippur, Umma, Sippar, Larsa, Kish, Adab, and Isin. Each of these walled urban centers controlled the surrounding lands and villages. Inside each city stood a large temple dedicated to particular god.

Around 3000 B.C. powerful local leaders became the kings of the city-states. Kingdoms were forged by these kings whose armies conquered neighboring city states with lances and shields. The city-states battled each other. Strong rulers were able to conquer their neighbors. Weak rulers were defeated. As time went on different city-states — such as Lagash, Uruk, Ur — were dominant. In general, however, the Sumerians appeared to have relatively peaceable during their 1,200 years of dominance in Mesopotamia. They didn’t make an effort create a large empire.

Marcos Such-Gutiérrez wrote in National Geographic History: Settlers arrived in the Mesopotamian floodplain around the sixth millennium B.C. These innovators devised an irrigation system of canals to harness the waters of the Tigris and Euphrates and better manage agriculture in the region. Their success created rich agricultural centers of trade. The wealth turned settlements into villages, and villages grew into cities with thousands of residents. [Source: Marcos Such-Gutiérrez, National Geographic History, August 25, 2023]

By 3500 B.C., Sumer had grown into a collection of city-states linked by linguistic and religious traditions. Among the most significant were Eridu, Uruk, Ur, Larsa, Isin, Adab, Lagash, Nippur, and Kish. Over time, some of them grew more powerful than others, and for brief periods, one city-state might rule the others until it fell from power. The Bible mentions Sumerian cities and rulers: “The beginning of his kingdom was Babel, Erech, and Accad, all of them in the land of Shinar. From that land he went into Assyria, and built Nineveh, Rehobothir, Calah,and Resen between Nineveh and Calah; that is the great city” (Genesis 10:10-12). [Source: Marcos Such-Gutiérrez, National Geographic History, August 25, 2023]

RELATED ARTICLES:

SUMERIANS: SUMER, HISTORY, ORIGINS, IRRIGATION africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN LIFE, CULTURE AND LANGUAGE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN RELIGION: CITY-STATE GODS, TEMPLES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN ART AND TREASURES FROM THE TOMBS OF UR africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN CITY STATES AND CITIES: URUK, LAGASH AND GIRSU africame.factsanddetails.com ;

UR: THE GREAT CITY OF SUMER AND HOMETOWN OF ABRAHAM africame.factsanddetails.com ;

NIPPUR: THE RELIGIOUS CENTER OF MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DECLINE OF THE SUMERIANS AND THEIR FALL TO THE AKKADIANS AND ELAMITES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

AKKADIANS: EMPIRE, SARGON. LANGUAGE, CULTURE africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character” by Samuel Noah Kramer (1971) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerians: A History from Beginning to End” by Hourly History (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerians” by Leonard Woolley (1927) Amazon.com;

“History Begins at Sumer” by Samuel Noah Kramer (1956, 1988) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerian World” by Harriet Crawford (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerian Civilization” (2022) Amazon.com;

Sumerian Theocratic Government

Sumer was a theocracy with slaves. Each city state worshiped its own god and was ruled by a leader who was said to have acted as an intermediary between the local god and the people in the city state. The leaders led the people into wars and controlled the complex water systems. Rich rulers built palaces and were buried with precious objects for a trip to the afterlife. A council of citizens may have selected the leaders.

Stela of Ur-Nammu Some scholars have described the Mesopotamian system of government as a "theocratic socialism." The center of the government was the temple, where projects like the building of dikes and irrigation canals were overseen, and food was divided up after the harvest. Most Sumerian writing recorded administrative information and kept accounts. Only priests were allowed to write.

Early Sumerians established a powerful priesthood that served local gods, who were worshiped in temples that dominated the early cities. Much of political and religious activity was oriented towards gods who controlled the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and nature in general. If people respected the gods and the gods acted benevolently the Sumerians thought the gods would provide ample sunshine and water and prevent hardships. If the people went against the wishes of the local god and the god was not so benevolent: droughts, floods, famine and locusts were the result.

In Uruk kings took part n important religious rituals. One vase from Uruk shows a king presenting a whole set of gifts to a temple of the city goddess Inana. Kings supported temples and were expected to turn over some of the booty from wars and raids to temples.

Some have called Sumer the epitome of the welfare city-state. Sam Roberts in the New York Times, “Work was a duty, but social security was an entitlement. It was personified by the Goddess Nanshe, the first real welfare queen immortalized in hymn as a benefactor who “brings the refugee to her lap, finds shelter for the weak.”... Nanshe, the Mesopotamian goddess, was hailed by some bards of Sumer for her compassion and, undoubtedly, denounced by others as a dupe." [Source: Sam Roberts, New York Times, July 05, 1992]

List of Rulers of Sumer

In the period before 2700 B.C., the Sumerians considered most of their kings to be gods, or at least heros. The Deification and Heroization of kings mostly ceased after Gilgamesh, king of Uruk around 2700 B.C.. The Gilgamesh of the epic was predominantly an Heroic, but tragic, figure. He was no god. Some early Sumerian tales about Gilgamesh make him appear ambivalent. He was not a great king. The story, "Gilgamesh and Agga of Kish," shows him forced to acknowledge the overlordship of the Great King of Kish, possibly Mesannepada of UR.

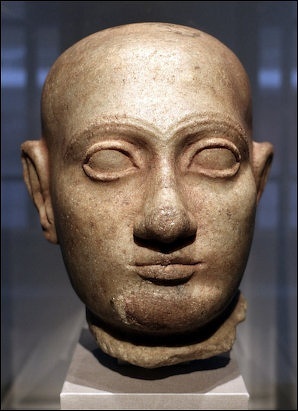

Gudea, king of Lagash, Sumer

Early Dynastic period:

Gilgamesh of Uruk (legendary): 2700 B.C.

Mesanepada of Ur: 2450 B.C.

Eannatum of Lagash: 2400 B.C.

Enannatum of Lagash: 2430 B.C.

Uruinimgina of Lagash: 2350 B.C.

Lugalzagesi of Uruk: 2350 B.C.

Dynasty of Akkad (Agade)

Sargon: 2340–2285 B.C.

Rimush: 2284–2275 B.C.

Manishtushu: 2275–2260 B.C.

Naram-Sin: 2260–2223 B.C.

Shar-kali-sharri: 2223–2198 B.C.

Dynasty of Lagash

Gudea(1): 2150–2125 B.C.

Third Dynasty of Ur

Ur-Nammu: 2112–2095 B.C.

Shulgi: 2095–2047 B.C.

Amar-Sin: 2046–2038 B.C.

Shu-Sin: 2037–2029 B.C.

Ibbi-Sin: 2028–2004 B.C.

Dynasty of Isin

Ishbi-Erra: 2017–1985 B.C.

Shu-ilishu: 1984–1975 B.C.

Iddin-Dagan: 1974–1954 B.C.

Lipit-Ishtar: 1934–1924 B.C.

Dynasty of Larsa

Rim-Sin: 1822–1763 B.C.

[Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "List of Rulers of Mesopotamia", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/meru/hd_meru.htm (October 2004)

Some women did obtain positions of power. Cuneiform tablets at Cornell described a 21st century B.C. Sumerian princess in the city of Garsana that has made scholars rethink the role of women in the ancient kingdom of Ur. According to the Los Angeles Times: “ The administrative records show Simat-Ishtaran ruled the estate after her husband died. During her reign, women attained remarkably high status. They supervised men, received salaries equal to their male counterparts' and worked in construction, the clay tablets reveal. "It's our first real archival discovery of an institution run by a woman," said David Owen, the Cornell researcher who has led the study of the tablets. Because scholars do not know precisely where the tablets were found, however, the site of ancient Garsana cannot be excavated for further information.” [Source: Jason Felch, Los Angeles Times, November 3, 2013]

King Shulgi of Ur, the Greatest Sumerian King

Shulgi, King of Ur (r c. 2029 BC – 1982 BC) was the second king of the Sumerian Renaissance in the Third Dynasty of Ur. He reigned for 48 years and is credited with completing the construction of the Great Ziggurat of Ur, begun by his father, and is known for his extensive revision of the scribal school's curriculum. Shulgi was the son of Ur-Nammu king of Ur — according to one later text (CM 48), by a daughter of the former king Utu-hengal of Uruk — and was a member of the Third dynasty of Ur. [Source: Wikipedia]

possibly Shulgi

Shortly after his father's death, Shulgi engaged in a series of punitive wars against the Gutians to avenge his father. The only activity recorded in the year-names for his first few years involved temple construction. He proclaimed himself a god in his 23rd regnal year. Numerous praise poems have been written for him. Some early chronicles chastise Shulgi for his impiety: "he did not perform his rites to the letter, he defiled his purification rituals" (The Weidner Chronicle (ABC 19)[3]) and improper tampering with the rites and composing "untruthful stelae, insolent writings" (CM 48[4]). The Chronicle of Early Kings (ABC 20)[5] accuses him of "criminal tendencies, and the property of Esagila and Babylon he took away as booty."

In his 20th year he claimed that the gods made him destroy the city of Der, apparently as some punishment. The inscriptions state that he "put its field accounts in order" with the pick-axe. In his 18th year-name his daughter was married off to the king of Elam. Following this, Shulgi engaged in a period of expansionism, conquering highlanders such as the Lullubi, Simurum and the Lulubum nine times between the 26th and 45th years of his reign. He also destroyed Kimash and Humurtu (cities to the east of Ur, somewhere in Elam) in the 45th year of his reign. Ultimately, Shulgi was never able to rule any of these distant peoples; at one point, in his 37th year, he was obliged to build a large wall in an attempt to keep them out.

In addition to construction of defensive walls and completion of the Great Ziggurat of Ur, Shulgi spent a great deal of time and resources in expanding, maintaining, and generally improving roads. He built rest-houses along roads, so that travelers could find a place to rest and drink fresh water or spend a night. Samuel Noah Kramer called him the builder of the first inn. Shulgi also boasted about his ability to maintain high speeds while running long distances. He claimed in his 7th regnal year to have run from Nippur to Ur, a distance of not less than 100 miles. Kramer refers to Shulgi as "The first long distance running champion."

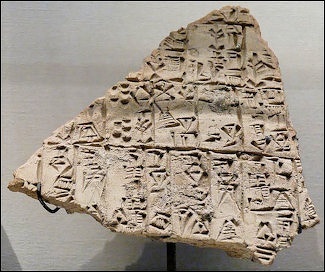

Inscription of Umma and Lagash, c. 2500 B.C., Emergence of Kingship

When first traceable in written records, Lagash in the south and Kish in the north were the rival cities, about 30 kilometers apart. Lagash was ruled by a king, Enkhegal. A little later Meselim, King of Kish, conquered all of southern Babylonia, including Lagash. After Meselim died, Ur-Nina founded a new dynasty at Lagash and became independant. Ur-Nina's grandson, Eannatum, raised the power of Lagash to its greatest height, conquering all the cities of Babylonia, even Kish. The Elamites were always invading the fertile plains of Babylonia, so Ennatum ascended the eastern mountains and subjugated Elam. [Source: George A. Barton, “Archaeology and the Bible”,” 7th Edition, "Inscription of Entemena #7" in: The Royal Inscriptions of Sumer and Akkad (New Haven, CT; Yale Univ., 1929) pp. 61, 63 and 65]

These documents below were found on clay cylinders and date from about 2500 B.C. At the time of the events recorded here, Entemena is king of Lagash. His uncle, Eannatum, had been king earlier and was responsible for the treaty with Lagash mentioned in these documents. The names of the rulers of Lagash are confusing: Eannatum was king of Lagash at the time the original treaty with Umma was negotiated. Enannatum was Eannatum's brother and succeeded him on the throne. Entemena, Enannatum's son and Eannatum's nephew, was king of Lagash at the time of the dispute described in the documents.

Inscription of Umma and Lagash

The Inscription of Umma and Lagash reads: I: “By the immutable word of Enlil, king of the lands, father of the gods, Ningirsu and Shara set a boundary to their lands. Mesilim, King of Kish, at the command of his deity Kadi, set up a stele [a boundary marker] in the plantation of that field. Ush, ruler of Umma, formed a plan to seize it. That stele he broke in pieces, into the plain of Lagash he advanced. Ningirsu, the hero of Enlil, by his just command, made war upon Umma. At the command of Enlil, his great net ensnared them. He erected their burial mound on the plain in that place.”

II: “Eannatum, ruler of Lagash, brother of the father of Entemena [who put up this inscription] ... for Enakalli, ruler of Umma, set the border to the land. He carried a canal from the great river to Guedin . He opened the field of Ningirsu on its border for 210 spans to the power of Umma. He ordered the royal field not to be seized. At the canal he inscribed a stele. He returned the stele of Mesilim to its place. He did not encroach on the plain of Mesilim. At the boundary-line of Ningirsu, as a protecting structure, he built the sanctuary of Enlil, the sanctuary of Ninkhursag .... By harvesting, the men of Umma had eaten one storehouse-full of the grain of Nina [goddess of Oracles], the grain of Ningirsu; he caused them to bear a penalty. They brought 144,000 gur,, a great storehouse full, [as repayment]. The taking of this grain was not to be repeated in the future.

Urlumma, ruler of Umma drained the boundary canal of Ningirsu, the boundary canal of Nina; those steles he threw into the fire, he broke [them] in pieces; he destroyed the sanctuaries, the dwellings of the gods, the protecting shrines, the buildings that had been made. He was as puffed up as the mountains; he crossed over the boundary canal of Ningirsu. Enannatum, ruler of Lagash, went into battle in the field of Ugigga, the irrigated field of Ningirsu. Entemena, the beloved son of Enannatum, completely overthrew him. Urlumma fled. In the midst of Umma he killed him. He left behind 60 soldiers of his force [dead] on the bank of the canal "Meadow- recognized-as-holy-from-the-great-dagger." He left these men-their bones on the plain. He heaped up mounds for them in 5 places. Then Ili Priest of Ininni of Esh in Girsu, he established as a vassal ruler over Umma.

III: “Ili, took the ruler of Umma into his hand. He drained the boundary canal of Ningirsu, a great protecting structure of Ningirsu, unto the bank of the Tigris above from the banks of Girsu. He took the grain of Lagash, a storehouse of 3600 gur . Entemena, ruler of Lagash declared hostilities on Ili, whom for a vassal he had set up. Ili, ruler of Umma, wickedly flooded the dyked and irrigated field; he commanded that the boundary canal of Ningirsu; the boundary canal of Nina be ruined.... Enlil and Ninkhursag did not permit [this to happen]. Entemena, ruler of Lagash, whose name was spoken by Ningirsu, restored their canal to its place according to the righteous word of Enlil, according to the righteous word of Nina, their canal which he had constructed from the river Tigris to the great river, the protecting structure, its foundation he had made of stone ....”

Sumerian King List

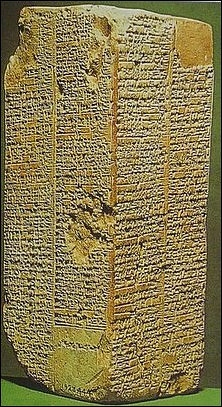

Sumerian Kings List

Marcos Such-Gutiérrez wrote in National Geographic History: The Sumerian city-states were ruled by kings, whose names might have been forgotten were it not for the discovery of the Sumerian King List. Copies of the list have been found on 16 different clay tablets or cylinders found across Mesopotamia. The most complete one features the names of prominent cities, their rulers, and how long they ruled. Scholars are quick to point out that the Sumerian King List blends legend and history, with the earliest kings enjoying excessively long reigns and the more recent having human-size lengths of time on the throne. [Source: Marcos Such-Gutiérrez, National Geographic History, August 25, 2023]

The Sumerian King List is written on a surviving clay tablet dated by a scribe who wrote it to the reign of King Utukhegal of Erech (Uruk), which places it around 2125 B.C. It reads: "After kingship had descended from heaven, Eridu became the seat of kingship. In Eridu Aululim reigned 28,800 years as king.[Source: piney.com; CSUN]

Alalgar reigned 36,000 years. Two kings, reigned 64,800 years. Eridu was abandoned and its kingship was carried off to Bad-tabira

At Badgurgurru Enmenluanna exercised (sovereignty) 43,200 years; Dumuzi the shepherd exercised it 36,000 years: 3 kings their years were 108,000.

Badgurgurra was overthrown; the sovereignty passed to Larak. At Larak Sibzianna exercised kingship 28,800 years; 1 king exercised it 28,000 years.

Larak was overthrown; the sovereignty to Sippar passed. At Sippar Enmenduranna exercised kingship 21,000 years: 1 king exercised it 21,000 years.

Sippar was overthrown; the sovereignty passed to Surrippak. At Surrippak Uberratum exercised sovereignty 18,6000 years: 1 king exercised it 18,600 years. Total: Five Cities, eight kings, reigned 241,200 years.

The deluge overthrew the land. After the deluge had overthrown, the sovereignty descended from heaven — the sovereignty was at Kish. At Kish Gaur was king. He exercised (sovereignty) 1200 years. Khulla-Nidaba, the divine maiden, exercised it 960 years. In Kish .... Total: twenty-three kings, reigned 24,510 years, 3 months, 3 1/2 days. Kish was defeated; its kingship was carried off to Eanna.

In Eanna, Meskiaggasher, the son of (the sun god) Utu reigned as En (Priest) and Lugal (King) 324 years — Meskiaggasher entered the sea, ascended the mountains. Enmerkar, the son of Meskiaggasher, the king of Erech who had built Erech, reigned 420 years as king. Lugalbanda, the shepherd, reigned 1,200 years. Dumuzi the fisherman, whose city was Kua, reigned 100 years. Gilgamesh, whose father was a nomad reigned 126 years. Urnungal, the son of Gilgamesh, reigned 30 years. Labasher reigned 9 years. Ennundaranna reigned 8 years. Meshede reigned 36 years. Melamanna reigned 6 years. Lugalkidul reigned 36 years. Total: twelve kings, reigned 2,130 years. Erech was defeated, its kingship was carried off to Ur...."

Royal Tombs of Ur

Manuel Molina Martos wrote in National Geographic History: Leonard Woolley excavated 16 tombs that he identified as royal because of their contents: lavish grave goods and evidence of mass human sacrifice. In most cases, the names of the royal figures are unknown except for two. One is Queen Puabi in tomb PG800, who was identified by the seal found near her body. Various inscriptions identified King Ur-Pabilsag who reigned around the period 2600–2450 B.C., Meskalamdug, his son Mesannepadda, and his sons A’anepada and Meski’ag-Nanna, who ruled sometime between the years 2450 and 2300 B.C. But these names have not been matched to specific tombs. [Source: Manuel Molina Martos, National Geographic History, May 22, 2019]

Inside the burial chamber itself lay the body of a woman on top of a funeral bier. She was covered with amulets and jewelry made of gold and precious stones. Her elaborate headdress was made of 20 gold leaves, lapis lazuli and carnelian beads, as well as a large golden comb. Near the body lay a cylinder seal that bore an inscription from which the archaeologists were able to identify the woman: Queen Puabi (in his notes, Woolley referred to her as Shubad because of a mistranslation). The seal made no mention of her husband, which led some to believe she could have been a queen in her own right. Alongside Puabi lay the bodies of two of her servants. In addition to her treasures and servants, Puabi was interred with her makeup, including a silver box that contained kohl, a black pigment used as eyeliner.

When the archaeologists pulled back the heavy wooden chest inside the tomb, they found a large hole. Amid huge anticipation they climbed through and dropped down into a large chamber below. On excavation, the patterns of burial and ritual in this tomb appeared to be similar to that of the queen’s above.

On the ramp leading into the chamber, they passed the bodies of six soldiers, laid out in two rows. Inside the chamber itself were two carriages, each pulled by three oxen, and beside them the bodies of the carriage drivers. At the back of the chamber the bodies of nine women lay, all richly ornamented, with their heads resting against the wall. In a gallery running parallel to the burial chamber were more women, along with numerous armed soldiers arranged in rows.

Woolley deduced that PG800 and the tomb below it, which he called PG789, housed the bodies of Queen Puabi and her husband, respectively. The man must have died first and been buried in the lower chamber. Then, when his consort Puabi died, it seems that the workers who constructed her tomb robbed the one below, concealing the hole they had made with the heavy chest. The quantity of treasure uncovered in these tombs was so great that when Woolley informed his colleagues of the finds by telegram, he did so in Latin, hoping that his erudite encryption would keep the secret safe.

Sumerian Warfare

There was virtually no evidence of warmaking in the early years of Sumer. Between 3100 B.C. and 2300 B.C. warfare started to play a bigger role in city-state relations as priest-kings were replaced by warlords with armies armed with lance and shields. Military tactics were developed, weapons started utilizing metals and the first "battles" begun taking place.

There is evidence that the king of Uruk went on military campaigns to bring back cedar wood from the mountains as early as early as 2700 B.C. and by 2284 B.C. Sumerian kings were fighting wars with neighboring cities and peoples like the Semites. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

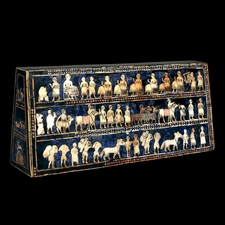

The earliest evidence of state-sponsored warfare is an inscribed stele, dated to 2500 B.C., found at Lagash (also known as Telloh or Ginsu). It described a conflict between Lagash and Umma for irrigation rights and was settled in a battle in which war wagons were used. The Standard of Ur, a Sumerian object dated to around 2500 B.C. included images of warfare with wheeled vehicles and warriors. The vehicles looked more like transport vehicles than a fighting ones.

Sumerian Warfare Tactics, Prisoners and Spies

Around 2500 B.C. soldiers started wearing metal helmets and organizing themselves into columns with a six man front. They wore cloaks and tunics that appeared to be strengthened with metal, and used four-wheeled carts driven by four horses (prototypes of armor and chariots). The even employed "death pits" in which enemies where lured into battlefield equivalents of holes with trapdoors where they picked off like proverbial sitting ducks. [Source: “History of Warfare” by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

The primary weapons were lances and shields. By the middle of the second millennium the Sumerians had developed the sophisticated composite bow and utilized method of siege craft (breaching and scaling) to attack fortresses. The results could sometimes be quite bloody. A 4500-year-old inscription from Lagash describes piles of bodies with as many as a thousand enemy corpses. The Mesopotamians also used psychological warfare to defeat their enemies. [Ibid]

Prisoners of war were not used as slaves but were deported to differents part of the kingdom. Sometimes they were sacrificed in temples. It seems only men were killed in battles and sieges and in sacrificial rites not women or children. Historian Ignace Gelb has argued that this was so because it was "relatively easy to exert control over foreign women and children" and "the state apparatus was still not strong enough to control masses of unruly male captives." As the power of the state increased males prisoners were "marked and branded" and "freed and resettled" or used as mercenaries or bodyguards to the king.

Spies were called scouts, or eyes. They were often employed to check out what was going on in rival kingdoms. The following is an Akkadian text from one "brother" king to another, complaining he had released the scouts according to a deal that was made but had not been paid the ransom as promised: "To Til-abnu: thus says Jakun-Asar your "brother? previously about the scout's release you wrote to me. As for the scouts which came in my power I have released. That I have indeed released (them) you know, still you have not sent the money for ransom. Every since I began releasing your scouts, you have consistently not provided the money for ransom. I here — and you there’should (both) release!"

Unraveling Sumerian History from the Stela of the Vultures

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: Sumer was a collection of city-states surrounded by agricultural land. As the city-states grew, so did the potential for border conflicts, such as one that raged for 200 years between Lagash and Umma, both in present-day Iraq. The Stela of the Vultures, which survives as seven fragments of what was once a six-foot slab of limestone, records Lagash’s eventual victory. One side depicts the god Ningirsu, holding his enemies in a sack, while the other shows a series of scenes from the conflict. A cuneiform account by Lagash’s leader, Eannatum, wraps around the stela: “Eannatum struck at Umma,” it reads. “The bodies were soon 3,600 in number....I, Eannatum, like a fierce storm wind, I unleashed the tempest!”

“The historical side depicts Eannatum leading a phalanx of soldiers trampling enemies underfoot, a victory parade, a funeral ceremony, and another, poorly preserved tableau — along with, at top, the image that gives the stela its name, a kettle of vultures consuming the heads of Umma soldiers. It is, in a way, a document both poetic and legal — it invokes the grace and power of Ningirsu, and stakes a claim to land won by force.

“Lagash’s primacy was short-lived. By the end of the period, Umma had plundered its rival and begun the consolidation of power that would result in the rise of the Akkadian Empire. The tradition of documenting battles in words and pictures continued, perhaps reaching a peak with the Assyrians in the seventh century B.C., when they carved elaborate battle reliefs in the North Palace of Nineveh in present-day Iraq, and documented the siege of Jerusalem on a series of octagonal clay prisms called Sennacherib’s Annals.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024