Home | Category: Sumerians and Akkadians

AKKADIANS

The Akkadians were Semitic-speaking people, which distinguished them from their their contemporaries, the Sumerians. Under Sargon of Akkad (r. ca. 2340–2285 B.C.), they established a political center in southern Mesopotamia and created the world's first empire, which at the height of its power united an area that included not only Mesopotamia but also parts of western Syria and Anatolia, and Iran. From about 2350 B.C. to the Persians took over in 450 B.C., Mesopotamia was largely ruled by Semitic-speaking dynasties with cultures derived from Sumer. They include the Akkadians, Eblaites and Assyrians. They fought and traded with the Hittites, Kassites and Mitanni, all possibly of Indo-European descent. [Source: World Almanac]

The Akkadians produced extraordinary bronze sculptures and codified laws. Their language was the lingua franca of Mesopotamia. Much of what archaeologists know about Akkadian life comes from a group of about 8,000 more prosaic cuneiform texts written in Akkadian and Sumerian on clay tablets. These include a large group of royal inscriptions and thousands of documents that record trading transactions and legal matters. Yale University Assyriologist Benjamin Foster told Archaeology magazine: , “The royal inscriptions tell us what the Akkadian kings thought was important about themselves,” says Foster, “while the administrative documents give a picture of the empire’s day-to-day operation.” But Assyriologists still have only a hazy picture of how Sargon built and maintained his empire. [Source: Kate Ravilious, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2022]

Morris Jastrow said: “Even in the oldest period to which our material enables us to trace the history of the Euphrates Valley, we witness the conflict for political control between Sumerians and Akkadians (that is between non-Semites and Semites). Lagash, Nippur, Ur, and Uruk are ancient Sumerian centres, but near the border-line between the southern and the northern sections of this valley a strong political centre is established at Kish, which foreshadows the growing predominance of the Semites. The rulers sometimes assume the title of “king,” sometimes are known by the more modest title of “chief,” a variation that suggests frequent changes of political fortunes. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

There are two names in this dynasty of Akkad with its centre at Agade that stand forth with special prominence—Sargon, and his son Naram-Sin. Sargon in fact marks an epoch in the history of the Euphrates Valley...The population is depicted on the monuments as Sumerian, and yet among the rulers we find one bearing a distinctly Semitic name,while some of the inscriptions of the rulers of Kish are clearly to be read as Semitic, and not as Sumerian. It is, therefore, not surprising to find the Semitic kings of Akkad, circa 2500 B.C., and even before the rise of Kish, reaching a position of supremacy that extended their rule far into the south, besides passing to the north, east, and west, far beyond the confines of Babylonia and Assyria.

RELATED ARTICLES:

DECLINE OF THE SUMERIANS AND THEIR FALL TO THE AKKADIANS AND ELAMITES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIANS: SUMER, HISTORY, ORIGINS, IRRIGATION africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN RULERS, GOVERNMENT, WARFARE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN LIFE, CULTURE AND LANGUAGE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN RELIGION: CITY-STATE GODS, TEMPLES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN ART AND TREASURES FROM THE TOMBS OF UR africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN CITY STATES AND CITIES: URUK, LAGASH AND GIRSU africame.factsanddetails.com ;

UR: THE GREAT CITY OF SUMER AND HOMETOWN OF ABRAHAM africame.factsanddetails.com ;

NIPPUR: THE RELIGIOUS CENTER OF MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com ;

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Age of Agade: Inventing Empire in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Benjamin R Foster (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Akkadian Empire: An Enthralling Overview of the Rise and Fall of the Akkadians”

by Enthralling History (2022) Amazon.com;

“A History of Sumer and Akkad: An Account of the Early Races of Babylonia from Prehistoric Times to the Foundation of the Babylonian Monarchy” by Leonard William King (1910) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamian History: Sumerians, Hittites, Akkadian Empire, Assyrian Empire, Babylon” by History Hourly (2021) Amazon.com;

“Nippur V: The Area WF Sounding: The Early Dynastic to Akkadian Transition (Oriental Institute Publications) by Augusta McMahon , McGuire Gibson, et al. (2006) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Volume I: From the Beginnings to Old Kingdom Egypt and the Dynasty of Akkad” by Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller, D. T. Potts, Amazon.com;

“Sargon: Great Kings of the Ancient World” by John D. Matloch Amazon.com;

“Sargon of Akkad: Founder of the Akkadian Empire” (Oriental Publishing) (2024) Amazon.com;

“Introduction to Akkadian” by Richard I. Caplice (1980) Amazon.com;

“Key to a Grammar of Akkadian” by John Huehnergard (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character” by Samuel Noah Kramer (1971) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerians: A History from Beginning to End” by Hourly History (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Near East” Volume One by James B. Pritchard (1965) Amazon.com;

“A History of the Ancient Near East” by Marc Van De Mieroop (2003) Amazon.com;

Akkadian Empire

The Akkadian Empire was the first state that brought many different peoples, territories, and city-states under one rule. Kate Ravilious wrote in Archaeology Magazine: The empire’s influence echoed through Mesopotamian history, with powerful leaders such as Hammurabi of Babylon (r. ca. 1792–1750 B.C.) and Sargon II of Assyria (r. 721–705 B.C.) modeling their reigns on those of early Akkadian rulers, who were known as members of the Dynasty of Ishtar, after their patron goddess.[Source: Kate Ravilious, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2022]

The Akkadians created the first Mesopotamian empire by forging together Ur, Mari and other cities. Dominating the region from 2300 to 2159 B.C., the Akkadians are regarded as the first people to conceive of creating a world empire. Akkadian armies marched across Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean and Anatolia and briefly ruled (2340-2180 B.C.) an empire that included the pine-covered mountains of present-day Lebanon and the silver mines of what is now southern Turkey.

Armed with composite bows, arrows and spears Akkadians armies led by King Saragon defeated the Sumerians in 2350 B.C. And conquered most of the territory that became the Akkadian empire. An inscription discovered at Ebla that described Saragon's victories read: "he worshipped the god Dagan, who gave from that time onwards the Upper Country, Mari, Yarmuti and Ebla, as far as the Forest or cedars and the Mountain of Silver."

Sargon called himself "King of Sumer and Akkad.” He came from a place called Kish and founded a capital called Agade, whose whereabouts remain unknown, and founded a dynasty that lasted from around 2300 to 2159 B.C. Sargon's grandson Naram-Sin was the first known Mesopotamian ruler to claim he was a god. An inscription found on a monument to himself read: Naram-Sin, the strong, the conqueror of...Ebla, never before subdued in history."

The Akkadians were unable to create a real, unified empire because Sargon and his successors were unable to establish local control. However the Akkadian language supplanted the Sumerian language in many places. In 2198 B.C., the Akkadian dynasty collapsed due to squabbling over royal succession and invasions by nomads and peoples from the surrounding mountains. The collapse also may have been connected to a 200-year drought in North and East Africa. After the decline of the Akkadians, Sumerian culture was revived and the region splint into small kingdom that frequently battled intruders from the east and west. Lagash was an independent city-state that re-emerged after the fall of the Akkadian Empire

Akkadian Period (ca. 2350–2150 B.C.)

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The period from approximately 2900 to 2350 B.C. in southern Mesopotamia (Sumer) is known as the Early Dynastic. During this time, Sumer was divided politically between competing city-states, each controlled by a dynasty of rulers. The succeeding period (ca. 2350–2150 B.C.) is named after the city of Agade (or Akkad), whose Semitic monarchs united the region, bringing the rival Sumerian cities under their control by conquest. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "The Akkadian Period (ca. 2350–2150 B.C.)", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The ideology and power of the empire was reflected in art that first displayed strong cultural continuity with the Early Dynastic period. When fully developed, it came to be characterized by a profound new creativity that marks some of the peaks of artistic achievement in the history of the ancient world. A new emphasis on naturalism, expressed by sensitive modeling, is manifested in masterpieces of monumental stone relief sculpture. Although little large-scale art of the period remains, a huge corpus of finely carved Akkadian seals preserves a rich iconography illustrating interactions between man and the divine world.” \^/

Akkadian period dice from Khafajah

Morris Jastrow said:“The times must have been ripe for a movement on so large a scale. As so often happens, the political upheaval was followed by a strong intellectual stimulus which shows itself in a striking advance in Art. One of the most remarkable monuments of the Euphrates Valley dates from this period. It depicts Naram-Sin, the son of Sargon, triumphing over Elam; and it seems an irony of fate that this magnificent sculptured stone should have been carried away, centuries later, as a trophy of war by the Elamites in one of their successful incursions into the Euphrates Valley. In triumphant pose Naram-Sin is represented in the act of humiliating the enemy by driving a spear through the prostrate body of a soldier, pleading for mercy. The king wears the cap with the upturned horns that marks him as possessing the attributes of divine power. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

“With Sargon and Ur-Engur we thus enter on a new era. Instead of a rivalry among many centres for political supremacy over the south or the north, we have Semites and Sumerians striving for complete control of the entire valley, with a marked tendency to include within their scope the district to the north of Akkad. This district, as a natural extension consequent upon the spread of the Sumero-Akkadian culture, was eventually to become a separate principality that in time reversed the situation, and began to encroach upon the independence of the Euphrates Valley.”

Akkadian Language

The Semitic language spoken by the Akkadians spoke was first recorded around 2500 B.C. It was a highly complex language that served as a common means of communication throughout the Middle East in the second millennium B.C. and was the predominate tongue of the region for more than 2,500 years.

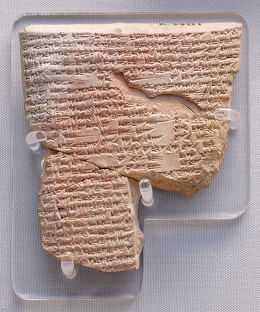

Akkadian existed as both a spoken and written language. Rachel Shin wrote in Fortune: Its cuneiform writing system used an alphabet of sharp, intersecting triangular figures. Akkadians typically wrote by marking a clay tablet with the wedge-shaped end of a reed (cuneiform literally means “wedge shaped” in Latin). Hundreds of thousands of these tablets, due to the durability of their material, have weathered the centuries and now populate the halls of various universities and museums [Source: Rachel Shin, Fortune, July 6, 2023 =]

Akkadian was a very important language. It was the common language in the ancient Middle East and Mesopotamia. People in Mesopotamia spoke different languages and used Akkadian as lingua franca — the same way English is used today.. Cuneiform, meanwhile, is one of the earliest writing systems, Originating around 3400 B.C., it was used as written language form for a number of ancient language, including Sumerian, Akkadian, Hittite, Aramaic, and Old Persian. The oldest surviving literary work, the Epic of Gilgamesh, discovered in 1853, was written over 4,000 years ago in the Akkadian language using cuneiform script. [Source: Jason Nelson, Decrypt Media, July 4, 2023]

The number of existing cuneiform texts is overwhelming compared to the small number of linguists who are able to translate Akkadian. This means that troves of knowledge on the significant early civilization, sometimes considered the first empire in history, are completely untapped. Right now, the number of existing tablets and the rate of new tablets being excavated by archaeologists outpace linguists’ translation efforts. But that could change with the integration of A.I. into the cuneiform interpretation process. =

“Hundreds of thousands of clay tablets inscribed in the cuneiform script document the political, social, economic, and scientific history of ancient Mesopotamia,” the team wrote. “Yet, most of these documents remain untranslated and inaccessible due to their sheer number and limited quantity of experts able to read them.” =

King Sargon

King Sargon (r. ca. 2340–2285 B.C.) was the ruler credited with forging the Akkadian Empire. Kate Ravilious wrote in Archaeology Magazine: According to legend, Sargon was born in secret in the city of Akkad to a priestess of the goddess Ishtar, who set him adrift on the Euphrates River where he was eventually found and adopted by a gardener living in Kish. Sargon became a cupbearer at the court of Ur-Zababa. “This allowed him direct access to the royal family, and it was an important role, giving him responsibility for the purity of foods served,” says Foster. The legend tells of a plot to murder Sargon that was thwarted by Inanna, demonstrating that the future king had divine protection. Sargon then overthrew Ur-Zababa, revealing an unprecedented appetite for power that would not be satisfied by becoming just the ruler of Kish. After establishing an extensive kingdom in northern Mesopotamia, Sargon went on to overthrow Ur-Zababa’s Sumerian nemesis Lugalzagesi and to conquer the Sumerian cities in the south, unifying all of Mesopotamia into one large state. “There was something special about Sargon,” says Foster. “For the first time in Mesopotamian history, a king didn’t spend his time fighting neighboring cities but turned his energies to foreign lands. No one had ever done this before.” [Source: Kate Ravilious, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2022]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: ““The city of Agade (Akkad) itself has not so far been located, but it was probably founded before the time of Sargon. Tradition credits Sargon with being the "cup bearer" of the king of Kish, at a time when Kish was an important and powerful city in the northern part of lower Mesopotamia. The name Sargon is a modern reading of Sharru-ken ("the king is legitimate"). Usurping power and assuming for himself the title of king, Sargon went on to conquer southern Mesopotamia and lead military expeditions to conquer further east and north.[Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "The Akkadian Period (ca. 2350–2150 B.C.)", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

Morris Jastrow said: King Saragon “is the first conqueror to inaugurate a policy of wide conquest that eventually gave to Babylonia and subsequently to Assyria a commanding position in the ancient world. While retaining his captial at Agade, he brings into prominence the neighbouring Sippar by devoting himself to the service of the sun-god Shamash at that place; and he either founds or enlarges the city Babylon which a few centuries later became the captial of the United Euphrates Valley; its frame was destined to outlast the memory of all the other centres of the south, and to become synonymous with the culture and religion of the entire district. The old enemy of Sumer on the east, known as Elam, with which Sumerian rulers had many a conflict , was forced to yield to the powerful Sargon. Far to the north the principality of Subartu—the later Assyria—and still father north the district known as Guti acknowledged the rule of Sargon and of his successors. The land to the west up to the Mediterranean coast, known under the general designation of Amurru, was also claimed by Sargon. The rulers of Lagash humbly call themselves the “servants” of the powerful conqueror; Cuthah, Uruk, Opis, and Nippur in the south, Babylon and Sippar in the north, are among the centres in the Euphrates Valley, specifically named by Sargon as coming under his sway. He advances to Nippur, and, by assuming the title “King of Akkad and of the Kingdom of Enlil,” announces his control of the whole of Sumer and Akkad. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

Sargon Mythology

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: The later Dynasty of Akkad, with its heroic figures Sargon and Narâm-Sin, formed a second, minor focus for the epic tradition. Sargon, the founder of the dynasty, figures in an unfortunately very fragmentary text in which he seems to have made the wife of his Sumerian opponent Lugal-zagge-si his concubine, but under what circumstances is not clear. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

Another story tells how he was protected by Inanna at the court of Ur-Zababa of Kish when he was serving there as cupbearer. The figure of Narâm-Sin seems to have become the type of the self-willed human ruler challenging the gods in his hubris. The epic tale called "The Fall of Akkad" tells, after describing the might and prosperity of Akkad, how Narâm-Sin, wishing to rebuild Enlil's temple Ekur in Nippur, failed to obtain favorable omens that would allow him to do so. Yet, against Enlil's will, Narâm-Sin mustered his forces and began demolishing Ekur. Enlil in his anger called in the wild Gutian mountaineers, who disrupted all communication in the country and produced dire famine. Lest the whole country be destroyed, the major deities of Sumer then appealed to Enlil and succeeded in having the punishment focused on Akkad as the actual offender. It was thoroughly cursed by the gods so that it would never again be inhabited.

Legend of Sargon and Its Parallels with the Moses Story

The birth story of Moses (Exodus 2:1-10) was probably recorded during the tenth century B.C. It has similarities with the birth account of King Sargon, who lived near the end of the third millennium B.C. It doesn’t seem improbable that people in ancient times hid unwanted children in such a way that they were found by rich or powerful people so the child wouldn’t have to die or force a family to struggle more than it already was. [Source: piney.com]

The Sargon account Cuneiform texts reads: 1. Sargon, the mighty king, king of Akkadê am I,

2. My mother was lowly; my father I did not know;

3. The brother of my father dwelt in the mountain.

4. My city is Azupiranu, which is situated on the bank of the Purattu [Euphrates],

5. My lowly mother conceived me, in secret she brought me forth.

6. She placed me in a basket of reeds, she closed my entrance with bitumen,

7. She cast me upon the rivers which did not overflow me.

8. The river carried me, it brought me to Akki, the irrigator.

[Source: George A. Barton, “Archaeology and the Bible”,” 3rd Ed., (Philadelphia: American Sunday-School Union, 1920), p. 310]

9 Akki, the irrigator, in the goodness of his heart lifted me out,

10. Akki, the irrigator, as his own son brought me up;

11. Akki, the irrigator, as his gardener appointed me.

12. When I was a gardener the goddess Ishtar loved me,

13. And for four years I ruled the kingdom.

14. The black-headed peoples I ruled, I governed;

15. Mighty mountains with axes of bronze I destroyed .

16. I ascended the upper mountains;

17. I burst through the lower mountains.

18. The country of the sea I besieged three times;

19 Dilmun I captured .

20. Unto the great Dur-ilu I went up, I . . . . . . . . .

21 . . . . . . . . . .I altered. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

22. Whatsoever king shall be exalted after me,

23. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

24. Let him rule, let him govern the black-headed peoples;

25. Mighty mountains with axes of bronze let him destroy;

26. Let him ascend the upper mountains,

27. Let him break through the lower mountains;

28. The country of the sea let him besiege three times;

29. Dilmun let him capture;

30. To great Dur-ilu let him go up.

The rest of the text is broken.

The German journalist Werner Keller wrote: “The basket-story is a very old Semitic folk-tale. It was handed down by word of mouth for many centuries. The Sargon legend of the third millennium B.C. is found on Neo-Babylonian cuneiform tablets of the first millennium B.C. It is nothing more than the frills with which prosperity has always loved to adorn the lives of great men.” [Source: Werner Keller, “The Bible as History,” 2nd revised Ed. Morrow & Co, NY, page 123, Skeptically.org]

Sargon’s Rule

Kate Ravilious wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Sargon had established the world’s first empire, joining a range of ethnicities with different beliefs and different languages under the same ruler. He sent Akkadian governors to oversee Sumerian cities and made Akkadian the empire’s official language. According to administrative documents, Sargon maintained a force of 5,400 men, the world’s first professional standing army. [Source: Kate Ravilious, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2022]

Sargon was in need of a reliable fighting force—the Sumerians did not submit willingly to Akkadian rule. “We know that the Sumerian cities revolted at least twice and that their rebellions were suppressed bloodily, with body counts in the tens of thousands— as much as one-third of the male population of fighting age,” says Assyriologist Ingo Schrakamp of the Free University of Berlin. The Akkadian army, outfitted with sophisticated weapons such as powerful composite bows, was always able to overpower the Sumerian forces, which were assembled from farmers and shepherds armed with simple lances, axes, and spears.

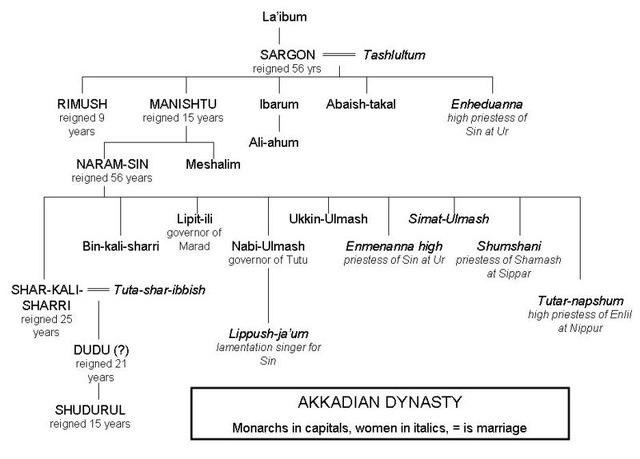

The Sumerian King List, a text whose earliest version dates to around 2000 B.C., charts the rise and fall of the Akkadian Empire, which began with Sargon and grew in the hands of his grandson Naram-Sin (r. ca. 2260–2223 B.C.) and his great-grandson Sharkalisharri (r. ca. 2223–2198 B.C.). Upon Sharkalisharri’s death, the empire collapsed, losing the Sumerian south. It continued as a regional northern state before coming to an end.

How Sargon Used Religion to Rule the Sumerians

Kate Ravilious wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Scholars believe that one way Sargon maintained his vast empire was by appointing members of the royal family to high priesthoods, beginning with his daughter, Enheduanna, whom he appointed as high priestess of the Sumerian moon god Nanna in the city of Ur. “I think this was a stroke of genius,” says Foster. “He made religion and the state into family affairs.”[Source: Kate Ravilious, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2022]

“When Sargon conquered the south, taking the land and installing his own governors, it would have been perceived by the Sumerians as stealing divinely owned property from the city gods,” says Schrakamp. Enheduanna’s main role, along with her counterparts appointed as high priests and priestesses in other Sumerian cities, was to control local clerics, weaken the status of the city gods, and impose the Akkadian religious hierarchy on Sumer. “She really believed in her mission, believed in the Akkadian Empire, believed in the passion of Inanna, and believed that any rebels should be brought to a horrible end,” says Foster. “She was a very bloodthirsty poet.”

Her relationship to the goddess Inanna was key to Enheduanna’s own political role in the wake of the failed revolt. “By evoking myths about a forceful, victorious Inanna, Enheduanna declares that Inanna, who used to be a minor goddess, has managed to surpass the other deities,” Zgoll says. “All of them are now submitted to her authority.” This intentional subordination of the Sumerian city gods in favor of the Akkadian national deity, Inanna, is further confirmed by a previously unknown myth referenced in some of the passages of “Ninmeshara.” Those passages refer to a hostile city overseen by Nanna and prophesy that Inanna will order Nanna to deliver terrible famine, fire, and suffering to its citizens if they continue to rebel. “This suggests that the unnamed hostile city is Ur,” says Zgoll, “and that it will be subdued by its own city god, Nanna, and will belong to Inanna.”

Enheduanna’s reluctance to name Ur directly and the cautious and roundabout way in which she tells this part of the story is no surprise given that, at the time of its composition, she was in exile from Ur and her future was precarious. In Zgoll’s reconstruction of this previously unknown segment, Inanna passes judgment on Ur and orders Nanna to execute that judgment. As a result, the city has no food, its gates are burned, and Akkadian soldiers swarm in and conquer it. Once again, Inanna is proclaimed ruler of all the lands. In the words of the poem, “The judgment is yours [Inanna], my Queen! Since that has made you even greater, since you have become the most powerful.”

As “Ninmeshara” and Enheduanna’s other poems reveal, military prowess only partially explains the success of the Akkadian Empire. Unifying the state under one overarching religion was crucial, too. Enheduanna’s Temple Hymns are evidence that she was essential to this restructuring of society. Each of the 42 hymns is about one city god and its temple and fits the Sumerian concept that every city was autonomous. But taken together, the hymns form a narrative that exalts the unity of a single state. “Enheduanna’s Temple Hymns helped to build this concept that was so fundamental for the realm,” says Zgoll.

Enheduanna’s songs confirm that Sargon’s imperial strategy went far beyond the act of conquest. “This was a family that believed in communication and believed in the force of ideology,” Foster says. “They had thought clearly about what it could do.” The elite Sumerian subjects of the Akkadian Empire who heard Enheduanna’s hymns and her songs praising the newly ascendant Inanna would have understood that a new order was at hand. It respected their city gods but subordinated the Sumerians to a greater imperial and religious power.

King Sargon’s Successors

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Sargon was succeeded by two of his sons, Rimush and Manishtushu, who consolidated the dynasty's hold on much of Mesopotamia. The Akkadian empire reached its apogee under Naram-Sin (r. ca. 2260–2223 B.C.), and there are references to campaigns against powerful states in the north, possibly including Ebla. At its greatest extent, the empire reached as far as Anatolia in the north, inner Iran in the east, Arabia in the south, and the Mediterranean in the west. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "The Akkadian Period (ca. 2350–2150 B.C.)", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Control of the empire was maintained under Naram-Sin's successor, Shar-kali-sharri (r. ca. 2223–2198 B.C.), though at the end of his reign there appears to have been a power struggle for the throne. A number of city rulers reestablished their independence in southern Mesopotamia, and the territory ruled over by the last kings of Agade (Dudu and Shu-Turul) had shrunk back to the region directly around the city.” \^/

Morris Jastrow said: Naram-Sin “continues the conquests of his father, and penetrates even into Arabia, so that he could well lay claim to the high-sounding title which he assumes of “King of the Four Regions.” The glory of this extensive kingdom thus established by Sargon and Naram-Sin was, however, of short duration. Agade was obliged, apparently, to yield first to Kish. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

“This happened not long after Naram-Sin’s death but, what is more significant, within about two centuries the Sumerians succeeded in regaining their prestige; and with their capital at Ur, an ancient centre of the moon-cult, Sumerian rulers emphasise their sovereignty of both south and north by assuming the title “King of Sumer and Akkad.” Ur-Engur, the founder of the dynasty (ca. 2300 B.C.), which maintained its sway for 117 years, is the first to assume this title, which, to be sure, is not so grandiloquent as that of “King of the Four Regions,” but rests on a more substantial foundation. It represents a realm that could be controlled, while a universal empire such as Sargon and Naram-Sin claimed was largely nominal—a dream in which ambitious conquerors from Sargon to Napoleon have indulged, and which could at the most become for a time a terrifying nightmare to the nations of the world.

“For some time after Ur-Engur had established a powerful dynasty at Ur, the Sumerians seem to have had everything their own way. His son and successor, Dungi, wages successful wars, like Sargon and Naram-Sin, with the nations around and again assumes the larger title of “King of the Four Regions.” He hands over his large realm, comprising Elam on the one side, and extending to Syria on the other, to his son Bur-Sin. We know but few details of the reign of Bur-Sin and of the two other members of the Ur dynasty that followed him, but the indications are that the Sumerian reaction, represented by the advent of the Ur dynasty, though at first apparently complete, is in reality a compromise. Semitic influence waxes stronger from generation to generation, as is shown by the steadily growing preponderance of Semitic words and expressions in Sumerian documents. The Semitic culture of Akkad not only colours that of Sumer, but permeates it so thoroughly as largely to eradicate the still remaining original and unassimilated Sumerian elements. The Sumerian deities as well as the Sumerians themselves adopt the Semitic form of dress. We even find Sumerians bearing Semitic names; and in another century Semitic speech, which we may henceforth designate as Babylonian, became predominant.

“On the overthrow of the Ur dynasty the political centre shifts from Ur to Isin. The last king of the Ur dynasty is made a prisoner by the Elamites, who thus again asserted their independence. The title “King of the Four Regions” is discarded by the rulers of Isin, and although they continue to use the title “King of Sumer and Akkad,” there are many indications that the supremacy of the Sumerians is steadily on the wane. They were unable to prevent the rise of an independent state with its centre in the city of Babylon under Semitic control, and about the year 2000 B.C., the rulers of that city begin to assume the title “King of Babylon.” The establishment of this so-called first dynasty of Babylon definitely foreshadows the end of Sumerian supremacy in the Euphrates Valley, and the permanent triumph of the Semites. Fifty years afterward we reach another main epoch, in many respects the most important, with the accession of Hammurabi to the throne of Babylon as the sixth member of the dynasty. During his long reign of forty-two years (ca. 1958-1916 B.C.), Hammurabi fairly revolutionised both the political and the religious conditions.”

Akkadians, Amorites and Hittites

Morris Jastrow said: “Two new factors begin about this time, and possibly even earlier, to exercise a decided influence in further modifying the Sumero-Akkadian culture; one of these is the Amoritish influence, the other is a conglomeration of peoples collectively known as the Hittites. From the days of Sargon we find frequent traces of the Amorites; and there is at least one deity in the pantheon of this early period who was imported into the Euphrates Valley from the west, the home of the Amorites. This deity was a storm god known as Adad, appearing in Syria and Palestine as Hadad. According to Professor Clay, most of the other prominent members of what eventually became the definitely constituted Babylonian pantheon betray traces of having been subjected to this western influence. Indeed, Professor Clay goes even further and would ascribe many of the parallels between Biblical and Babylonian myths, traditions, customs, and rites to an early influence exerted by Amurru (which he regards as the home of the northern Semites) on Babylonia, and not, as has been hitherto assumed, to a western extension of Babylonian culture and religion. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

“It is too early to pronounce a definite opinion on this interesting and novel thesis; but, granting that Professor Clay has pressed his views beyond legitimate bounds, there can no longer be any doubt that in accounting for the later and for some of the earlier aspects of the Sumero-Akkadian civilisation this factor of Amurru must be taken into account; nor is it at all unlikely that long before the days of Sargon, a wave of migration from the north and north-west to the south and south-east had set in, which brought large bodies of Amorites into the Euphrates Valley as well as into Assyria. The circumstance that, as has been pointed out, the earliest permanent settlements of Semites in the Euphrates Valley appear to be in the northern portion, creates a strong presumption in favour of the view which makes the Semites come into Babylonia from the north-west.

“Hittites do not make their appearance in the Euphrates Valley until some centuries after Sargon, but since it now appears that ca. 1800 B.C. they had become strong enough to invade the district, and that a Hittite ruler actually occupied the throne of Babylonia for a short period, we are justified in carrying the beginnings of Hittite influence back to the time at least of the Ur dynasty. This conclusion is strengthened by the evidence for an early establishment of a Hittite principality in north-western Mesopotamia, known as Mitanni, which extended its sway as early at least as 2100 B.C. to Assyria proper.

“Thanks to the excavations conducted by the German expedition at Kalah-Shergat (the site of the old capital of Assyria known as Ashur), we can now trace the beginnings of Assyria several centuries further back than was possible only a few years ago. The proper names at this earliest period of Assyrian history show a marked Hittite or Mitanni influence in the district, and it is significant that Ushpia, the founder of the most famous and oldest sanctuary in Ashur, bears a Hittite name. The conclusion appears justified that Assyria began her rule as an extension of Hittite control. With a branch of the Hittites firmly established in Assyria as early as ca. 2100 B.C., we can now account for an invasion of Babylonia a few centuries later. The Hittites brought their gods with them, as did the Amorites, and, with the gods, religious conceptions peculiarly their own. Traces of Hittite influence are to be seen e.g., in the designs on the seal cylinders, as has been recently shown by Dr. Ward, who, indeed, is inclined to assign to this influence a share in the religious art, and, therefore, also in the general culture and religion, much larger than could have been suspected a decade ago.

“Who those Hittites were we do not as yet know. Probably they represent a motley group of various peoples, and they may turn out to be Aryans. It is quite certain that they originated in a mountainous district, and that they were not Semites. We should thus have a factor entering into the Babylo-nian-Assyrian civilisation—leaving its decided traces in the religion—which was wholly different from the two chief elements in that civilisation—the Sumerian and the Akkadian.”

Importance of Religion to the Akkadians

Assyriologist Annette Zgoll told Archaeology magazine:“This is a world that is really focused on gods and their demands and needs,” says Zgoll. “All these different myths tell us how humans were created in order to serve the gods—to feed them, clothe them, and make music for them.” People believed that the gods were responsible for their success and that rituals such as the performance of Enheduanna’s song “Ninmeshara” were an essential part of placating them and winning them to one’s side. “We can read between the lines of ‘Ninmeshara’ and see that Enheduanna is afraid of Inanna,” Zgoll says. “She understands that the goddess might be angry with her and she asks herself, ‘What have I done wrong? How is it that horrible things are happening to me?’” [Source: Kate Ravilious, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2022]

Kate Ravilious wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Three clay cuneiform tablets dating to around 1750 B.C. are inscribed with passages of Enheduanna’s poem written in praise of the goddess Inanna."Ninmeshara” begins with a description of Inanna’s conquest of her enemies. This suggests to Zgoll that the events described in the poem as it survives may not reflect the original order of the text as Enheduanna composed it. “A Mesopotamian myth doesn’t normally forgo a proper introduction,” she says. “We don’t know why she conquers her enemies, so a prior event must have occurred.” By analyzing the text’s hylemes, Zgoll has been able to piece together the events making up the story, rearranging them into what she believes to be their original chronological order. This fresh structure has enabled her to locate places where information is missing but implied from surrounding text or cultural context.

In its rearranged form “Ninmeshara” begins with the god An, the Sumerian equivalent of the Akkadian god Il, giving Inanna the instruments of power. These were sacred weapons that allowed her to control fire, generate storms, ride on fearsome predators, and unleash terrifying disasters. The poem describes how enemies arise from Sumer, a reference to the well-attested Sumerian revolt during the reign of Naram-Sin. An and Enlil, god of wind, air, earth, and storms, pass judgment on the Sumerian rebels. Inanna then uses her instruments of power to destroy her enemies and become sovereign of all lands. “We can see that the song is a device for the mutual empowerment of the goddess and Enheduanna, her priestly human servant, in the hopes of resolving a critical political situation that affects events both in heaven and on Earth,” says Zgoll. “It ends with Inanna being the most powerful deity of all.”

High priests and priestesses were responsible for ritual ceremonies and for writing and performing new poems in praise of the gods. This prestigious position gave Enheduanna an outlet for her literary talents. Although Akkadian is thought to have been her first language, Enheduanna wrote in Sumerian, the language of the south. Uniquely for her time, she declares her authorship and names herself “I, Enheduanna” in the text of two songs praising Inanna. One of these, known as “Ninmeshara,” which Zgoll translates as “Inanna, Lady of the Countless Instruments of Power,” narrates events that occurred when the Sumerians revolted against Enheduanna’s nephew, Naram-Sin. “Ninmeshara” has long been revered as an important sacred scripture in Mesopotamia, and some 100 clay tablet versions of it exist, all of which postdate Enheduanna’s death and were copied or recopied up to 500 years after she wrote the song. In addition to “Ninmeshara,” Enheduanna is credited with writing the so-called Temple Hymns, a cycle consisting of 42 short poems, each dedicated to a single city god and its temple. [Source: Kate Ravilious, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2022]

Inana’s Blessing of Agade

Inana (Ishtar, Inanna) is known for blessing the city of Agade" (capital of Akkad and the Akkadian Empire of King Sargon) and then causing its fall. As the goddess of war and strife, she held the title Ninkur-ra-igi-ga, "the queen who eyes the highland" meaning that other lands feared her. Battle was called the "dance of Inanna, and she was at the very heart of it. She was "the star of the battle-cry, who can make brothers who have lived together in harmony fight each other". [Source: piney.com]

After Enlil had slaughtered the land of Unug in the dust as if it were a mighty bull, he gave the south as far as the highlands to Sargon, king of Agade. At that time, holy Inana established the sanctuary of Agade as her celebrated woman's domain; she set up her throne in Ulmac. Inanna got Ea drunk and got the power of the ME away from Ea. She would use such powers as that of "the eldership, musical worship and kissing the phallus" to enhance her own kingdom.

The story of “Ishtar’s Cursing of Agade” reads: “Like a young man building a house for the first time, like a girl establishing a woman's domain, holy Inana did not sleep as she ensured that the warehouses would be provisioned; that dwellings would be founded in the city; that its people would eat splendid food; that its people would drink splendid beverages; that those bathed for holidays would rejoice in the courtyards; that the people would throng the places of celebration; that acquaintances would dine together; that foreigners would cruise about like unusual birds in the sky; that even Marhaci would be re-entered on the tribute rolls; that monkeys, mighty elephants, water buffalo, exotic animals, as well as thoroughbred dogs, lions, mountain ibexes, and alum sheep with long wool would jostle each other in the public squares.

“She then filled Agade's stores for emmer wheat with gold, she filled its stores for white emmer wheat with silver; she delivered copper, tin, and blocks of lapis lazuli to its granaries and sealed its silos from outside. She endowed its old women with the gift of giving counsel, she endowed its old men with the gift of eloquence. She endowed its young women with the gift of entertaining, she endowed its young men with martial might, she endowed its little ones with joy.

“The nursemaids who cared for the general's children played the aljarsur instruments. Inside the city tigi drums sounded; outside it, flutes and zamzam instruments. Its harbour where ships moored was full of joy. All foreign lands rested contentedly, and their people experienced happiness. Its king, the shepherd Naram- Suen, rose as the daylight on the holy throne of Agade. Its city wall, like a mountain, reached the heavens. It was like the Tigris going to the sea as holy Inana opened the portals of its city-gates and made Sumer bring its own possessions upstream by boats. The highland Martu, people ignorant of agriculture, brought spirited cattle and kids for her. The Meluhans, the people of the black land, brought exotic wares up to her. Elam and Subir loaded themselves with goods for her as if they were packasses. All the governors, the temple administrators, and the accountants of the Gu-edina regularly supplied the monthly and New Year offerings.

“What a weariness all these caused at Agade's city gates! Holy Inana could hardly receive all these offerings. As if she were a citizen there, she could not restrain the desire to prepare the ground for a temple. But the statement coming from the E-kur was disquieting. Because of Enlil all Agade was reduced to trembling, and terror befell Inana in Ulmac. She left the city, returning to her home. Holy Inana abandoned the sanctuary of Agade like someone abandoning the young women of her woman's domain. Like a warrior hurrying to arms, she removed the gift of battle and fight from the city and handed them over to the enemy.”

Inana’s Cursing of Agade

The tone of the of “Ishtar’s Cursing of Agade” then changes: “ Not even five or ten days had passed and Ninurta brought the jewels of rulership, the royal crown, the emblem and the royal throne bestowed on Agade, back into his E-cumeca Utu took away the eloquence of the city. Enki took away its wisdom. Anu took up into the midst of heaven its fearsomeness that reaches heaven. Enki tore out its well-anchored holy mooring pole from the abzu. Inana took away its weapons. The life of Agade's sanctuary was brought to an end as if it had been only the life of a tiny carp in the deep waters, and all the cities were watching it. [Source: piney.com]

“Like a mighty elephant, it bent its neck to the ground while they all raised their horns like mighty bulls. Like a dying dragon, it dragged its head on the earth and they jointly deprived it of honour as in a battle. Naram- Suen saw in a nocturnal vision that Enlil would not let the kingdom of Agade occupy a pleasant, lasting residence, that he would make its future altogether unfavourable, that he would make its temples shake and would scatter its treasures. He realized what the dream was about, but did not put into words, and did not discuss it with anyone. Because of the E-kur, he put on mourning clothes, covered his chariot with a reed mat, tore the reed canopy off his ceremonial barge, and gave away his royal paraphernalia.

“Naram- Suen persisted for seven years! Who has ever seen a king burying his head in his hands for seven years? Then he went to perform extispicy on a kid regarding the temple, but the omen had nothing to say about the building of the temple. For a second time he went to perform extispicy on a kid regarding the temple, but the omen again had nothing to say about the building of the temple.

“In order to change what had been inflicted upon him, he tried to to alter Enlil's pronouncement. Because his subjects were dispersed, he now began a mobilization of his troops. Like a wrestler who is about to enter the great courtyard, he (lifted) his hands towards the E-kur. Like an athlete bent to start a contest, he treated the giguna as if it were worth only thirty shekels. Like a robber plundering the city, he set tall ladders against the temple. To demolish E-kur as if it were a huge ship, to break up its soil like the soil of mountains where precious metals are mined, to splinter it like the lapis lazuli mountain, to prostrate it, like a city inundated by Ickur.

“Though the temple was not a mountain where cedars are felled, he had large axes cast, he had double-edged agasilig axes sharpened to be used against it. He set spades against its roots and it sank as low as the foundation of the Land. He put axes against its top, and the temple, like a dead soldier, bowed its neck before him, and all the foreign lands bowed their necks before him. He ripped out its drain pipes, and all the rain went back to the heavens. He tore off its upper lintel and the Land was deprived of its ornament.

“From its "Gate from which grain is never diverted", he diverted grain, and the Land was deprived of grain. He struck the "Gate of Well-Being" with the pickaxe, and well-being was subverted in all the foreign lands. As if they were for great tracts of land with wide carp-filled waters, he cast large spades to be used against the E-kur. The people could see the bedchamber, its room which knows no daylight.

“The Akkadians could look into the holy treasure chest of the gods. Though they had committed no sacrilege, its lahama deities of the great pilasters standing at the temple were thrown into the fire by Naram- Suen. The cedar, cypress, juniper and boxwood, the woods of its giguna, were...... by him. He put its gold in containers and put its silver in leather bags. He filled the docks with its copper, as if it were a huge transport of grain. The silversmiths were re-shaping its silver, jewellers were re-shaping its precious stones, smiths were beating its copper. Large ships were moored at the temple, large ships were moored at Enlil's temple and its possessions were taken away from the city, though they were not the goods of a plundered city.

“With the possessions being taken away from the city, good sense left Agade. As the ships moved away from was removed. Enlil, the roaring storm that subjugates the entire land, the rising deluge that cannot be confronted, was considering what should be destroyed in return for the wrecking of his beloved E-kur. He lifted his gaze towards the Gubin mountains, and made all the inhabitants of the broad mountain ranges descend . Enlil brought out of the mountains those who do not resemble other people, who are not reckoned as part of the Land, the Gutians, an unbridled people, with human intelligence but canine instincts and monkeys' features. Like small birds they swooped on the ground in great flocks. Because of Enlil, they stretched their arms out across the plain like a net for animals.”

Akkadian Art and Culture

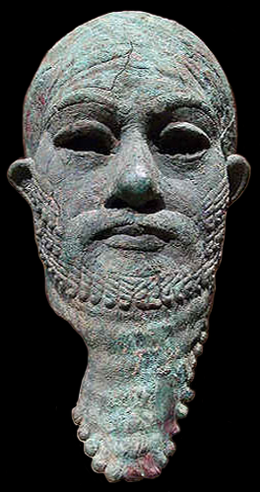

Kate Ravilious wrote in Archaeology Magazine: The Akkadians oversaw startling innovations in arts and literature throughout Mesopotamia. Artisans who had previously created abstract and geometric sculptures began to produce detailed figures, with faces expressing individual personalities. A regal copper head found in the ancient city of Nineveh provides a classic example: With a strong gaze, elaborate coiffure, and carefully groomed beard, the sculpture projects power, and may even depict Sargon himself. [Source: Kate Ravilious, Archaeology Magazine, November/December 2022]

Reliefs such as the disk depicting Enheduanna, Sargon’s daughter, and her assistants as well as engraved stone cylinder seals form the largest body of art from the Akkadian period. Rather than the softer local stone used in the pre-empire period, Akkadian imperial seals were commonly carved in serpentine—a more valuable stone that was much harder to work with. Akkadian artisans depicted dramatic events such as battles that pitted heroes against animals. A seal found in the cemetery of Ur that belonged to Enheduanna’s official hairdresser shows just such a scene.

Enheduanna is history’s first known attributed author and new analysis of her sacred songs demonstrates her central political role. “The rituals that Enheduanna performed were instrumental in creating the new power structure by reconciling the city-states and the wider realm,” says Zgoll. Her research has offered new interpretations of Enheduanna’s songs that are helping scholars understand how she became indispensable to Sargon’s heirs in their struggle to maintain power across Mesopotamia and as far away as the Mediterranean Sea. Enheduanna is now the focus of research aimed at understanding a historical figure who, while she lived, was critical to the Dynasty of Ishtar’s success—and was almost certainly the most powerful woman in the world.

Using AI to Decipher and Translate Akkadian

AI is increasingly be used to translate dead languages such Akkadian.Rachel Shin wrote in Fortune: There are so few people who can read the extinct language that nearly a million Akkadian texts still haven't been translated to date—but now an A.I. tool can decode them within seconds....An interdisciplinary group of computer science and history researchers published a journal article in May describing how they had created an A.I. model to instantly translate the ancient glyphs. The team, led by a Google software engineer and an Assyriologist from Ariel University, trained the model on existing cuneiform translations using the same technology that powers Google Translate. [Source: Rachel Shin, Fortune, July 6, 2023]

In translating dead languages, especially those with no descendant languages, piecing together meaning without a wealth of cultural context can be like traveling without a North Star. Akkadian is just such a language....Translation is often misunderstood as a one-to-one decryption of a foreign word or phrase. But many times, a statement in one language doesn’t have an exact or easy equivalent in another, accounting for cultural nuance and difference in the languages’ construction. High-quality translation requires a deep knowledge of both languages’ structures, their surrounding cultures, and the histories that anchor those cultures. Translating a text while preserving its original tone, cadence, and even humor is a delicate craft—and an incredibly difficult one when the language’s culture is largely unknown.

The A.I. can perform two types of translation—translating cuneiform to English, and transliterating cuneiform (rewriting it phonetically). The A.I.’s skill at the two translation types of translation scored 36.52 and 37.47, respectively, on the Best Bilingual Evaluation Understudy 4 (BLEU4), a measure of translation quality. These scores were above the team’s target, and are both high enough to be considered high-quality translations. BLEU4 scores on a scale of 0 to 100 (or 0 to 1) with 70 being the highest that could be realistically achieved by a very skilled human translator.

For decades, computer-generated translations were brittle and unreliable, Tom McCoy, a computational linguist at Princeton University, said. Translation programs embedded with grammatical rules always missed the richness of meaning in idioms and nonliteral language that slip through the cracks of formal grammar. But recently, A.I. programs like the cuneiform translator have been able to get at the “fuzzier” areas of language. It heralds an exciting new period of A.I.-propelled computational linguistics.

“In recent A.I., the big new thing is statistical processing, which is another type of math but not the sort of rigid rules that people were working with before,” McCoy said. “Statistics got us kind of over the hump of previous methods. We're now working with machine learning and deep learning. Machines are able to learn all these idiosyncrasies, idioms, and exceptions to rules, which is what was missing in the previous generation of A.I.”

The cuneiform A.I.’s translations still had mistakes—and had “hallucinations” as is common with A.I. In one example, it translated “Why should we (also) conduct the lawsuit before a man from Libbi-Ali?” as “They are in the Inner City in the Inner City.”Despite occasional errors, the tool still saved huge amounts of time and human labor in its initial processing of the texts. “A.I. currently is remarkable but unreliable. So it can do really amazing things, but you can never really trust the output it produces,” McCoy said of using A.I. for translation. “This means that the best case for using A.I. is something where it's very labor intensive, hard for humans to do, but once A.I. has given you some output, it's easy for humans to verify it.”

The model was most accurate when translating shorter sentences and formulaic texts like administrative records. It was also—surprisingly to the researchers—able to reproduce genre-specific nuances in translation. In the future, the A.I. will be trained on larger and larger samples of translations to further improve its accuracy, the researchers wrote. For now, it can assist researchers by producing preliminary translations that humans can then check for accuracy and refine in nuance.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024