Home | Category: Sumerians and Akkadians / Religion

SUMERIAN RELIGION

Samuel Noah Kramer has argued that the Sumerians may have invented religion by building huge temples called ziggurats in their cities and establishing priestly castes devoted to the ritual worship of specific deities, Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: Which god was the mightiest in the vast Sumerian pantheon depended on the place and time: the sky god Anu, for example, was popular in early Uruk, while the storm god Enlil was worshiped in Sumer. Inanna — the "Queen of Heaven" — may have originally been a fertility goddess in Uruk; her worship spread to other Mesopotamian cities, where she was known as Ishtar, and may have influenced the goddesses of later civilizations, such as Astarte among the Hittites and the Greek Aphrodite.

A story very like that of the Hebrew Bible's Noah, who built an ark stocked with animals to preserve his family during a great flood caused by divine wrath, is related in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Archaeologists think it was originally a Sumerian story from about 2150 B.C. — centuries before the Hebrew version was written. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, September 12, 2022]

Samuel Noah Kramer wrote: The Sumerians believed that the universe and everything in it were created by four deities: the heaven-god An, the air-god Enlil, the water-god Enki, and the mother-goddess Ninhursag. To help them operate the universe effectively, these four deities, with Enlil as their leader, gave birth to, or "fashioned," a large number of lesser gods and goddesses, and placed them in charge of its various components and elements. All the gods were anthropomorphic and functioned in accordance with duly prescribed laws and regulations; though originally immortal, they suffered death if they over-stepped their bounds. [Source: Samuel Noah Kramer, Encyclopaedia Judaica, Encyclopedia.com]

Man was created for the sole purpose of serving the gods and supplying them with food and shelter, hence the building of temples and the offering of sacrifices were man's prime duties. Sumerian religion, therefore, was dominated by priest-conducted rites and rituals; the most important of these was the New Year sacred marriage rite celebrating the mating of the king with the goddess of love and procreation. Ethically, the Sumerians cherished all the generally accepted virtues. But sin and evil, suffering, and misfortune were, they believed, also divinely planned and inevitable; hence each family had its personal god to intercede for them in time of misfortune and need. Worst of all, death and descent to the dark, dreary netherworld were man's ultimate lot, and life on earth was therefore man's most treasured possession.

See Separate Articles: MESOPOTAMIAN RELIGION africame.factsanddetails.com

RELATED ARTICLES:

SUMERIANS: SUMER, HISTORY, ORIGINS, IRRIGATION africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN RULERS, GOVERNMENT, WARFARE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN LIFE, CULTURE AND LANGUAGE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN ART AND TREASURES FROM THE TOMBS OF UR africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SUMERIAN CITY STATES AND CITIES: URUK, LAGASH AND GIRSU africame.factsanddetails.com ;

UR: THE GREAT CITY OF SUMER AND HOMETOWN OF ABRAHAM africame.factsanddetails.com ;

NIPPUR: THE RELIGIOUS CENTER OF MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DECLINE OF THE SUMERIANS AND THEIR FALL TO THE AKKADIANS AND ELAMITES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

AKKADIANS: EMPIRE, SARGON. LANGUAGE, CULTURE africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Sumerian Gods and Their Representations” by Irving L. Finkel, Markham J. Geller (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion” by Thorkild Jacobsen (1976) Amazon.com;

“Sumerian Mythology” by Samuel Noah Kramer (1998) Amazon.com;

“Anunnaki Gods: The Sumerian Religion” by Joshua Free Amazon.com;

“The Anunnaki Bible: The Sumerian Text's Origin of the Judeo Christian Bibles”

by Donald M Blackwell (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character” by Samuel Noah Kramer (1971) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerians: A History from Beginning to End” by Hourly History (2023) Amazon.com;

“History Begins at Sumer” by Samuel Noah Kramer (1956, 1988) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerian World” by Harriet Crawford (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Sumerian Civilization” (2022) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“A Handbook of Ancient Religions” by John R. Hinnells (2007) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary” by Jeremy Black (1992) Amazon.com;

“The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture” by Francesca Rochberg Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography” by Wayne Horowitz (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Social World of the Babylonian Priest” by Bastian Still (2019) Amazon.com;

Sumerian Theocratic Government

The Sumerians didn’t establish an empire like the Romans did. They lived in a bunch of independent city-states like the Greeks. Each city was seen as the property of one of the gods in the Sumerian pantheon, and the city’s ruler served as that god’s representative. The most important and prominent structure in a Sumerian city was the temple to its main god. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2020]

Sumer was a theocracy with slaves. Each city state worshiped its own god and was ruled by a leader who was said to have acted as an intermediary between the local god and the people in the city state. The leaders led the people into wars and controlled the complex water systems. Rich rulers built palaces and were buried with precious objects for a trip to the afterlife. A council of citizens may have selected the leaders.

Some scholars have described the Mesopotamian system of government as a "theocratic socialism." The center of the government was the temple, where projects like the building of dikes and irrigation canals were overseen, and food was divided up after the harvest. Most Sumerian writing recorded administrative information and kept accounts. Only priests were allowed to write.

Early Sumerians established a powerful priesthood that served local gods, who were worshiped in temples that dominated the early cities. Much of political and religious activity was oriented towards gods who controlled the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and nature in general. If people respected the gods and the gods acted benevolently the Sumerians thought the gods would provide ample sunshine and water and prevent hardships. If the people went against the wishes of the local god and the god was not so benevolent: droughts, floods, famine and locusts were the result.

See Separate Article: SUMERIAN RULERS, GOVERNMENT, WARFARE africame.factsanddetails.com

Nippur: the Religious Center of Mesopotamia

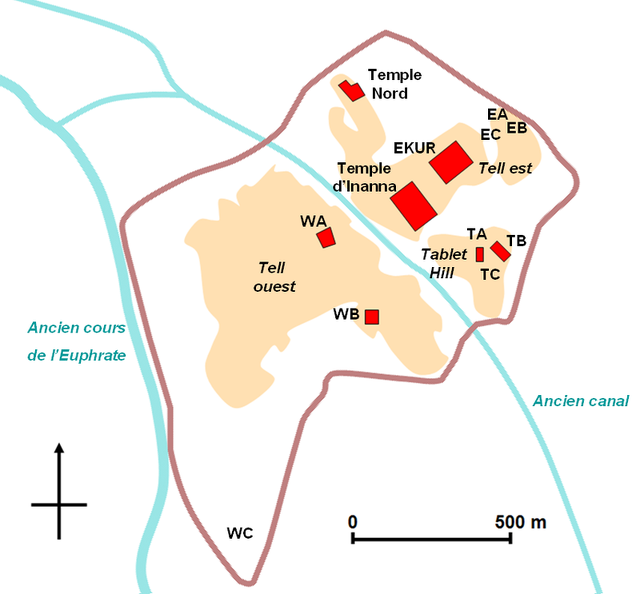

Nippur (pronounced ‘nĭ poor’) was a major religious center of Mesopotamia. Established by the pre-Mesopotamian“Ubaid” people around 4,500 B.C., Nippur was seat of the cult of Enlil, one of the most important Mesopotamian gods. It was never an important city-state and was ruled by other city-states. It is possible, but improbable, that Nippur was the "Calneh" mentioned in Genesis 10 of the Old Testament. Nippur is located 160 kilometers south of Baghdad, 100 kilometers east of present-day Najaf, and 80 kilometers southeast of Babylon on the canal Sha al-Nil, which was at one time, perhaps when Nippur was founded, was a separate branch of the Euphrates River.

According to the Oriental Institute ofThe University of Chicago: “In the desert a hundred miles south of Baghdad, Iraq, lies a great mound of man-made debris sixty feet high and almost a mile across. This is Nippur, for thousands of years the religious center of Mesopotamia, where Enlil, the supreme god of the Sumerian pantheon, created mankind. Although never a capital city, Nippur had great political importance because royal rule over Mesopotamia was not considered legitimate without recognition in its temples. Thus, Nippur was the focus of pilgrimage and building programs by dozens of kings including Hammurabi of Babylon and Ashurbanipal of Assyria. Despite the history of wars between various parts of Mesopotamia, the religious nature of Nippur prevented it from suffering most of the destructions that befell sites like Ur, Nineveh, and Babylon. The site thus preserves an unparalleled archaeological record spanning more than 6000 years. [Source: Oriental Institute of The University of Chicago ^^]

“Objects can often tell us things that were not written down. Elaborately designed items made of precious metals, stones, exotic woods, and shell allow us to reconstruct the development of ancient Mesopotamian art, as well as the far-flung trading connections that brought the materials to Babylonia. Egyptian, Persian, Indus Valley, and Greek artifacts also found their way to Nippur. Even after Babylonian civilization was absorbed into larger empires, such as Alexander the Great's, Nippur flourished. In its final phase, prior to its abandonment around A.D. 800, Nippur was a typical Muslim city, with minority communities of Jews and Christians. At the time of its abandonment, the city was the seat of a Christian bishop, so it was still a religious center, long after Enlil had been forgotten.” ^^

See Separate Article: NIPPUR: THE RELIGIOUS CENTER OF MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com

Girsu’s God Ningirsu

As we said Each city in Sumer was seen as the property of a Sumerian god. ,Girsu was a major city in the city-state known as Lagash. It was discovered in 1877 by Ernest de Sarzec, a French diplomat. A half century of excavations unearthed thousands of inscribed clay tablets, multiple statues, and the remains of many buildings. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2020]

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: Girsu belonged to Ningirsu, the heroic warrior god charged with combating demons and maintaining the cosmic order. A number of the chaos-inciting demons that Ningirsu fought were believed to inhabit a mountain in the northeastern reaches of the Sumerian world, in the region of present-day Turkey where the Tigris and Euphrates originate.

“By defeating the demons in this mountain, Ningirsu tames the two rivers and makes irrigation possible on the food plain,” says Rey. “Thus, he is considered a god of irrigation and agriculture, as well as the personifcation of foods.” One of the creatures Ningirsu was renowned for vanquishing was Imdugud, a thunderbird, or an eagle with the head of a lion. Rather than killing Imdugud, though, Ningirsu tamed it and adopted it as his avatar.

The most important and prominent structure in a Sumerian city was the temple to its main god. Rey says that the earliest tablets excavated at Girsu suggest that its original temple to Ningirsu predated the city itself, and served as a nucleus around which the urban center developed. Over the centuries, the temple was rebuilt multiple times, and, from the beginning, the tablets indicate, its name was “Eninnu, the White Thunderbird.” Eninnu, which means House Fifty, refers to the 50 divine powers of Enlil, the chief Sumerian god, who granted them to his son, Ningirsu. “When they say ffty powers, it’s equivalent to infnity,” says Rey. “You could translate it as the ‘almighty house’ or the ‘house of infnite powers.’” On the other hand, “White Thunderbird” identified the temple as the embodiment of Ningirsu.

See Separate Article: SUMERIAN CITY STATES AND CITIES: URUK, LAGASH AND GIRSU africame.factsanddetails.com

Eninnu Temple in Girsu

The main temple in Girsu is known as Temple of the White Thunderbird. Dr Sebastien Rey, an archaeologist with British Museum and head of excavations at Girsu, told Archaeology magazine the earliest tablets excavated at Girsu suggest that its original temple to Ningirsu predated the city itself, and served as a nucleus around which the urban center developed. Over the centuries, the temple was rebuilt multiple times, and, from the beginning, the tablets indicate, its name was “Eninnu, the White Thunderbird.” Eninnu, which means House Fifty, refers to the 50 divine powers of Enlil, the chief Sumerian god, who granted them to his son, Ningirsu. “When they say fifty powers, it’s equivalent to infinity,” says Rey “You could translate it as the ‘almighty house’ or the ‘house of infinite powers.’” On the other hand, “White Thunderbird” identifed the temple as the embodiment of Ningirsu. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2020]

In their excavations of Girsu, archaeology de Sar zec and his successors uncovered a series of Eninnu temples dating from around 2700 to 2200 B.C. in an area of the site they called the Mound of the Maison des Fruits. “These nineteenth and early twentieth-century excavations were poorly recorded,” says Rey, “but based on what we can say from reconstructing the stratigraphy, there were at least four or five Eninnu temples built right on top of each other—all the way to just before the time of Gudea.” The French archaeologists didn’t reach the bottom of this deposit, and evidence of even earlier temples may remain undiscovered. They also never found Gudea’s Eninnu, which would become one of the most sought-after structures in all of Mesopotamia.

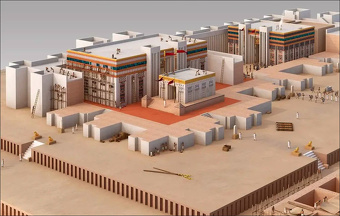

Among the temple’s features were a great dining hall, a room hung with weapons, a gem storehouse, a wine cellar, a brewery, a harp chamber, a chapel, and a courtyard that, the poem recounts, resounded with prayer and kettledrums. The finished structure was at once magnifcent and ferocious, according to the cylinders’ inscriptions, which read: “The House, being a great mountain, bordered on heaven, being the sun, it filled mid-heaven with light, being Eninnu, the White Thunderbird, it [attacked] the mountain with spread wings.”

Excavations of the temple revealed well-preserved mudbrick walls measuring up to 13 feet thick, along with pottery and other objects dating to the late third millennium B.C. Several weeks later, as they revealed more such walls, they found a fve-inch-long clay cone placed in one of them. These cones are very common in Mesopotamia, and, like most of them, this one contained a dedicatory inscription. When the cone was removed from the wall, it was found to read: “For Ningirsu, mighty hero of Enlil, Gudea, ruler of Lagash, made everything function as it should, and built for him his Eninnu, the White Thunderbird, and restored it to its proper place.”

During three full seasons of excavating Gudea’s Eninnu, Rey’s team has discovered a vast range of artifacts. Among these are a white cylinder seal—a mark of individual identity that could be used to roll out a sort of signature on a tablet—that belonged to the god Ningirsu himself. “Since the god is the owner of the state, he would have had a cylinder seal just like a king or a merchant,” says Rey. The seal, carved from a shell brought from the Persian Gulf, depicts Ningirsu in his human form, wearing a horned tiara and standing in his temple, which is surrounded by bearded guards. They also found a ceramic head of a roaring lion as well as a carved shell amulet that may depict Pazuzu, a “good” demon who protected pregnant women and newborn children from the depredations of bad demons.

Construction of Eninnu Temple

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: During his first year of excavations, de Sarzec discovered a pair of clay cylinders in a drain at Girsu. Each cylinder measures just under two feet tall and nine inches across, and together they are inscribed with a nearly 1,400-line poem, the longest-known Sumerian literary work. It describes the dreams in which Ningirsu visited Gudea, the ruler of Girsu, as well as the lengths to which the ruler went to build and consecrate the temple. “This is unique,” says Piotr Michalowski, an emeritus professor of ancient Near Eastern languages and civilizations at the University of Michigan. “We don’t have a text like this for any other Mesopotamian temple construction.” [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2020]

One of the statues found by de Sarzec depicts Gudea as an architect with a building plan resting on his knees and is inscribed with an abridged description of the Eninnu’s construction. Inscriptions on many of the other known statues of the ruler, even those dedicated to gods other than Ningirsu, go out of their way to boast that he built the Eninnu. “Gudea was clearly obsessed with this temple, and it seems to have been the crowning event of his reign,” says Michalowski. “The amount of manpower, resources, and treasure that it required, as well as the level of social engagement, was quite enormous.”

To prepare for the temple’s construction, the cylinder and statue inscriptions recount, Gudea purified the city, banishing the ritually unclean or unpleasant-looking and forbidding debt collection and burial of bodies. From locales such as Elam and Susa in Iran, Magan in Oman, the Amanus Mountains in Turkey, and Meluhha, likely in the Indus Valley, he procured an impressive array of valuable materials: cedar, ebony, and fir, wood; bitumen, gypsum, carnelian, diorite, and alabaster; and copper, silver, and gold. “All luxury goods in Mesopotamia had to come from afar because there was nothing there, just some low-quality limestone and shrubby trees,” says Michalowski.“Gudea’s reach was quite something if he was able to import all these things as he claimed.”

The cylinders relate that Gudea was a hands-on overseer, eagerly assisting various skilled laborers and personally stretching rope to obtain precise measurements. When it came time to lay the frst brick, the ruler molded the clay himself with great ceremony. And when the brick proved to be “most beautiful,” all of Lagash spent the day in celebration. t.

When Gudea introduced Ningirsu to the temple, the ruler commanded the entire population to kneel down and prostrate themselves. The god entered the complex as “a storm roaring toward battle” and emerged “like the sun god rising above Lagash.” As a reward for his efforts, Gudea was showered with acclaim, and his land grew ever more abundant.

Rey estimates that the entire Eninnu complex covers more than 40,000 square feet. By a stroke of luck, the frst walls the team unearthed were very close to the temple’s most sacred section—the cella, or inner sanctum. There, the researchers excavated the podium on which the Sumerian high priests would have placed a statue of Ningirsu. In front of the podium, they found an offering table with traces of burning, most likely from incense. A statue of Gudea, almost certainly the one with the building plan and description of the Eninnu’s construction, would have faced the podium as well. There were also a large number of clay bowls and cups that the priests would have used to carry offerings of food and beer to Ningirsu.

Plans, Math and Layout of Eninnu Temple

In the 1800s, a building plan for the temple was found on the lap of the statue of Gudea. Archaeologists have debated whether it represents a generic temple layout or the actual bluetprint of Gudea’s Eninnu. Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine:After decoding the plan’s scale, which is laid out in a number of sets of evenly spaced lines at the front of the tablet, Rey and his team compared the plan with the results of their excavations. They targeted a spot where the plan indicated a temple gate should be located. “After a couple of weeks of excavation, we found the foundations of a gate exactly where we had predicted they would be,” says Rey. “It’s as if we had a treasure map.”

According to this map, the temple complex had six gates in all. In addition to the one identifed using the statue plan, the team has excavated the gate that led to the temple’s inner sanctum. This gate was flanked by two towers, and beneath one of them, archaeologists unearthed a deposit commemorating the beginning of the temple’s construction. The deposit contained a white stone tablet bearing a dedication attesting that Gudea had built the Eninnu for Ningirsu. This inscription was identical to the one Rey had found on the clay cone in the temple wall. The same text was inscribed on a large stone door socket at the threshold of the temple’s inner sanctum, and on the fne limestone vessels imported from eastern Iran. This message is repeated over and over again, to insist on the legacy of the king, the importance of the god, and the name of the temple, says Rey. “It’s like a mantra.”

By the end of the team’s third season, they had found 17 identical inscribed cones embedded in the temple’s walls. The inscriptions wrap around the cones, and more than half of them were oriented so that Ningirsu’s name faced the heavens. A smaller number had Gudea’s name pointing up, and still others gave the temple’s name pride of place. The researchers studied the overall arrangement of the cones and found that while they did not adhere to any geometric pattern, they might have been intended to represent a constellation. They are currently working to re-create the star map above Girsu at the time of Gudea to test this notion.“From the Sumerian texts, we know that the stars were extremely important in their religious rituals,” says Rey. One example of this is the goddess Nanshe’s interpretation of the dream that inspired Gudea to build the Eninnu, in which she suggested that a bright star foretold that the project would be a success. Perhaps through the cones’ arrangement, Gudea was calling on the stars to help his dream project flourish once he had labored to make it a reality.

On the math behind the project, Craig Simpson wrote in The Telegraph: The measuring “ruler” appeared like a tally going up in marks from one line to six lines before stopping, in a system that has perplexed experts for more than a century. Dr Rey’s team worked on a theory that, unlike distance where numbers keep going, the Sumerian system worked more like time on a clock, getting so far before the measuring began again. The ancient architectural plan would therefore be divided into repeating fractions of distance.They then mapped on to the newly unearthed site the fractional measuring system they had been theorising, and realised that it worked perfectly and the site was divided into distances of “one to six” in the Sumerian system, whose terminology is unknown, with each unit corresponding to around eight modern meters. [Source: Craig Simpson, The Telegraph, November 20, 2023]

The thickness of the temple walls is four meters, which maps perfectly on to half a Sumerian unit. Dr Rey said that the system would have been flexible, and other measurements could have been inputted into turn system of units which could be scaled up or down. The modelling proved the Sumerians appeared to work from precise plans, like the one immortalised on the Gudea statue, that they could scale up to the huge dimensions of a temple.

Sumerian Temple Rituals and Activity

Sumerians continued a tradition of constructing temple after temple to a given god at the same spot. “There would have been a daily ritual of waking the god, clothing him, feeding him, and basically looking after him throughout the day,” says archaeologist Ashley Pooley, a supervisor of the Girsu excavation told Archaeology magazine. “Then they would put him to bed at night and close up the temple.” [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2020]

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: The cella’s layout ensured that visitors did not directly face the statue of Ningirsu when entering. “The statue is considered to be imbued with energy, what the Sumerian texts call ‘radiance,’” says Rey. “It was so intensely powerful that it would burn your eyes, like looking at the sun for too long.” The temple was not seen as an inert structure, but as an entity that performed the functions of the god—it was the White Thunderbird. This explains, for Rey, why its walls were so thick, far thicker than would have been necessary for structural reasons. “It’s like a nuclear reactor,” he says, “which has extremely thick walls to contain the extremely powerful energy inside.”

Entry to the temple was limited to those in the religious hierarchy. Several times each year, however, during festivals held in honor of Ningirsu, the energy of the Eninnu spilled beyond its confines and swept up the general populace. These festivals are believed to have lasted three or four days, and to have consisted of a procession in which the god’s statue was paraded in a sacred chariot from the Eninnu, out of the city, into the countryside, and then back to the holy precinct, where a religious feast was held.

Rey has found evidence of one of these feasts dating to the mid-third millennium B.C., and similar rituals are believed to have continued during Gudea’s reign several centuries later. Near thick layers of ash left behind by ritual fires, Rey excavated an eight-foot-deep pit containing more than 250 broken ceremonial goblets, along with the bones of sheep and other animals thought to have been sacrificed during the feast. “Looking at these orderly heaps of broken ceremonial beer mugs, you feel so close to these people who lived more than 4,000 years ago,” says Pooley. “Though rather tipsy from all the beer they’d been drinking, they seem to have queued up in a very orderly manner and chucked their ceremonial mugs into the pit. The larger population is mute to us because they didn’t write anything down, but there in that section you see them acting as a mass, and I find that quite amazing.”

Did the Sumerians Practice Human Sacrifice?

During Sir Charles Leonard Woolley’s excavation of Ur from 1922 to 1934, any burial without a tomb chamber was given the name ‘death pit’. The most impressive was PG 1237, which Woolley dubbed as ‘The Great Death Pit’, due to the number of bodies that were found in it. It is commonly believed that these individuals were sacrificial victims who accompanied their masters or mistresses in the afterlife.

According to the University of Pennsylvania: “PG1237 included 6 men and 68 women. The men, near the tomb’s entrance, had weapons. Most of the women were in four rows across the northwest corner of the death pit; six under a canopy in its south corner; and, six near three lyres near the southeast wall. Almost all wore simple headdresses of gold, silver, and lapis; most had shells with cosmetic pigments. Body 61 in the west corner was more elaborately attired than the others. Half the women (but none of the men) had cups or jars, suggestive of banqueting. Body 61 held a silver tumbler close to her mouth. The neat arrangement of bodies convinced Woolley the attendants in the tombs had not been killed, but had gone willingly to their deaths, drinking some deadly or soporific drug. He suggested that in so doing they were assured a “less nebulous and miserable existence” than ordinary men and women.

Manuel Molina Martos wrote in National Geographic History: The archaeologists’ discoveries revealed much about royal Sumerian burial rituals. There could be no doubt that the Sumerians practiced human sacrifice: Twenty-five sacrificed bodies were found in the tomb of Queen Puabi and 75 in the tomb of her husband. Another chamber dubbed the Great Death Pit, tomb PG1237, contained 74 bodies . Many theorize that these people poisoned themselves before burial, but some bodies bear evidence of trauma. By the end of the dig Woolley had enough evidence to describe in some detail the macabre funeral rites of the kings and queens of ancient Ur. [Source: Manuel Molina Martos, National Geographic History, May 22, 2019]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, Archaeology magazine, Live Science, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Natural History magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024