Home | Category: Death and Mummies

STUDY OF MUMMIES

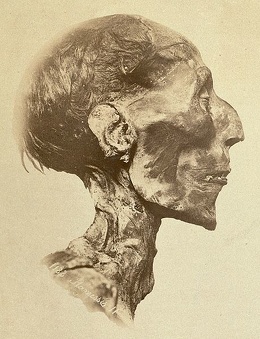

Thutmose II mummy When the first mummy studies began in the early 19th century, those examined were almost always those brought back as souvenirs from wealthy tourists' travels in Egypt. Nowadays mummies are examined with CT scans, X-rays and other modern technology tools.

A number of important discoveries were made by the “German Mummy Project” using the latest scientific tools for analysis. In 2004 German scientist at Tuebingen University and the Munich-based Doerne Institute discovered why mummies have lasted for thousands of years. They found that chemical found in the cedar resins used in the embalming process contained a chemical called guaiacol that was very effective in deterring the growth of bacteria without damaging body tissues.

Edward Rothstein wrote in the New York Times, “Through the analysis of one Peruvian child... it was learned that the mummy’s preservation was more than an accident of climate. The skin bore traces of copal, a tree resin, which was evidence of deliberate embalming. Through CT scans, researchers have learned that in life mummies have suffered many illnesses and indignities as well. [Source: Edward Rothstein, New York Times, June 16, 2011]

One mummy showed evidence of a congenital heart problem. Another had signs of bone malformation. Yet another, of a woman in the Hungarian tomb, showed advanced tuberculosis, which she probably passed on to her husband and son, who are also displayed here. Analysis of hair in some Peruvian mummies found traces of nicotine and coca and signs of a fish- or plant-based diet. Worn teeth in an Egyptian mummy hinted at a diet of hard, coarse grains. DNA analysis has been used to guess at regions of origin.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MUMMIES: HISTORY, PURPOSE, OLDEST AND SPECIAL ONES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MUMMIES AROUND THE WORLD: MUMMIFICATION, SOUTH AMERICA AND THE OLDEST ONES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MUMMY-MAKING: EMBALMING, GUIDES, HISTORY africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MUMMY BUSINESS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: PRICES, LABOR, WASTE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MUMMIFICATION WORKSHOPS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: ROOMS, EQUIPMENT AND EMBALMING INGREDIENTS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN-ERA MUMMIES: RITUALS, GOLD AND STUNNING FAIYUM PORTRAITS OF THE DEAD africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ANIMAL MUMMIES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MUMMY MANIA: MEDICINES, UNWRAPPING PARTIES, MOVIES africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Scanning the Pharaohs: CT Imaging of the New Kingdom Royal Mummies”

by Zahi Hawass and Sahar Saleem (2018) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Mummies and Modern Science” by Rosalie David (2008) Amazon.com;

“Mummies, Magic and Medicine in Ancient Egypt: Multidisciplinary Essays for Rosalie David” (2016) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Mummies: Unraveling the Secrets of an Ancient Art” by Bob Brier (1994) Amazon.com;

“The Mummy Makers of Egypt” by Tamara Bower (2016) Amazon.com;

“Mummy in Ancient Egypt: Equipping the Dead for Eternity” by Salima Ikram and Aidan Dodson (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Encyclopedia of Mummies” by Bob Brier (1998) Amazon.com;

“Mummies and Death in Egypt” by Françoise Dunand (1998, 2006) Amazon.com;

“In Search of the Immortals: Mummies, Death and the Afterlife”

by Howard Reid (2014), mummies around the world Amazon.com;

Examining an Egyptian Mummy with CT Scans, X-Rays and MRI

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: Researchers examined a 2,900-year-old mummy using X-rays, CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. They found that he suffered from Hand-Schuller-Christian’s disease, a very rare condition that left him with lesions in his skull and spine. A large hole on his frontal-parietal bone can be readily seen in this image. His brain appears to have been removed. Hand-Schuller-Christian disease causes so-called Langerhans cells, a type of immune cell found in the skin, to multiply rapidly. These cells tend to replace the normal structure of the bone and other soft tissue in the body. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science published April 28, 2012]

Normally MRI scans can't be used on mummies, because mummy bodies don't have any water in them. A recently developed technique, however, let the researchers use it to study the mummy of an Egyptian man who likely died in his 20s. In this scan it can be seen that the embalmers filled the back of the mummy's head with a resinlike fluid. The recently developed MRI technique allowed the researchers to get an up-close look at the inter-vertebral disks of the mummy's spine.

Curiously the sarcophagus the mummy was put in belonged to that of a woman named Kareset who lived about 2,300 years ago. The tests showed that the mummy is a man and definitely not Kareset. This image shows the mummy's preserved penis on a CT scan. An image of the mummy's pelvic area was taken using the new MRI technique. The researchers think the man also suffered from a type of diabetes that would have left his kidneys unable to conserve water. The result would have been that he was thirsty, hungry and urinating all the time.

What Mummies Tell Us About Ancient Egyptian Health

Mummy expert Dr. Arthur Aufderheide estimates that only 10 percent to 15 percent of mummies show the cause of death. They are more revealing about chronic ailments, the presence of parasites and determining what people ate (if their intestines are still there).

In 1910, Marc Armand Ruffer, a French microbiologist, found dried eggs of the schistosomiasis worm in kidneys of two 3000-year-old mummies. Schistosomiasis remains a disease that is prevalent in Egypt today. In other mummies he found gallstones, inflamed intestines, and a spleen that had apparently been enlarged by malaria. Ruffer looked inside ancient blood vessels and found calcified spots — evidence of hardening of the arteries, surprising considering the ancient Egyptians ate a low-fat high-fiber diet with a lot of grains. Ruffer invented a solution of salts for rehydrating ancient tissues (some researchers today use fabric softener) and popularized the term “paleopathology.”

Over the decades scientists have learned to glean information from ancient bones. Leprosy, anemia, stunted growth, syphilis and tuberculosis leave behind characteristic marks in the eye sockets, spine and other bones. Bones also leave behind clues about arthritis and vitamin deficiencies and can indicate whether a person who died violently such as being struck by an ax or knife or a blunt instrument. Even so 80 percent of ailments — plague, aneurisms, measles and others — leave behind no clues or marks.

CT Scans of Mummies Reveal Tattoos and Unretreived Brain-Scooping Tool

In 2014, the British Museum hosted an exhibition with eight of the museum’s mummies displayed with detailed three-dimensional images of their insides and 3-D printed replicas of some of the items buried with them. Scientists produced the images using CT scans and sophisticated imaging software that probed beneath the bandages, revealing skin, bones, preserved internal organs — and in one case a brain-scooping rod left inside a skull by embalmers. Bio-archaeologist Daniel Antoine said the goal of the exhibition was to present museum’s wrapped corpses “not as mummies but as human beings.”[Source: Associated Press, April 9, 2014 ]

Associated Press reported: “The museum has been X-raying its mummies since the 1960s, but modern CT scanners give a vastly sharper image... Volume graphics software, originally designed for car engineering, was then used to put flesh on the bones of the scans — showing skeletons, adding soft tissue, exploring the nooks and cavities inside. The eight mummies belong to individuals who lived in Egypt or Sudan between 3,500 B.C. and 700 A.D. They range from poor people naturally preserved in sand — the cheapest burial option — to high-ranking Egyptians given elaborate ceremonial funerals. “You got what you paid for, basically,” said museum mummy expert John Taylor. “There were different grades of mummification.”

“Embalmers were exceptionally skilled, extracting the brain of the deceased through the nose, although they sometimes made mistakes. The museum’s scientists were thrilled to discover a spatula-like probe still inside one man’s skull, along with a blob of brain. “The tool at the back of the skull was quite a revelation, because embalmers’ tools are something that we don’t know much about,” Taylor said. “To find one actually inside a mummy is an enormous advance.” The man, who died around 600 B.C., also had painful dental abscesses that might have killed him. Another mummy, a woman who lived in Sudan around 700 A.D. was a Christian with a tattoo of the Archangel Michael’s name on her inner thigh.

“The star of the show is Tamut, a temple singer from a family of high-ranking priests who died in Thebes around 900 B.C. Her brightly decorated casket, covered in images of birds and gods, has never been opened, but the scans have revealed in extraordinary detail her well-preserved body, down to her face and short-cropped hair. Tamut was in her 30s or 40s when she died, and had calcified plaque inside her arteries — a sign of a fatty diet, and high social status. She may well have died from a heart attack or stroke. Several amulets carefully are arranged on her body, including a figure of a goddess with its wings spread protectively across her throat. It’s even possible to see beeswax figurines of gods placed inside her chest to protect the internal organs in the afterlife.

““The clarity of the images is advancing very rapidly,” Taylor said. “As the technology advances, we have hopes that we may be able to read even hieroglyphic inscriptions on objects inside mummies.” MacGregor said the museum plans eventually to scan all 120 of its Egyptian and Sudanese mummies, and to reveal even more about their lives. “Come back in another five years and you will hear Tamut sing,” he said.”

CT Scans of Heart Mummies Don’t Contain Hearts

Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science: When scientists peered beneath the wrappings of two small ancient Egyptian mummies thought to hold human hearts, they were taken aback: Not only were there no noticeable hearts inside, but the remains were not even human. Rather, one of the mummies is tightly packed with grain and mud — a so-called corn or grain mummy — while the other holds the remains of a bird, possibly a falcon, that is missing a body part and several organs, the researchers found. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, July 25, 2020]

The two mummies, both interred in sarcophagi, have been housed at Haifa Museum for about 50 years. However, "records were not kept as diligently as they are now," so not much is known about them except that they're more than 2,000 years old, Ron Hillel, registrar and head of collection management of Haifa Museums, told Live Science.

Over the past few years, the National Maritime Museum in Haifa has been going through its collection and determining the best way to preserve each artifact. When curators came across the two mummies, they realized they didn't know what was inside. The records noted they contained mummified hearts, but "we did the research and it didn't make sense," Hillel said. Often, (but not always) "the hearts were left in the body," of Egyptian mummies, Hillel said, because the ancient Egyptians thought that when people died, their hearts would be weighed against a feather representing ma'at, an Egyptian concept that includes truth and justice, Live Science previously reported. If the heart weighed the same or less than the feather, these people would earn eternal life; if not, they would be destroyed.

The CT scans done at Rambam Hospital revealed that the mummies had very different insides from one another. The roughly 18-inch-long (45 centimeters) human-shaped mummy — designed to look like Osiris, the god of the afterlife, the dead, life and vegetation — contained mud and grains."During Osiris festivals that were held, [the ancient Egyptians] would produce these," Hillel said. "It would be a mixture of a clay or sand with these grains, and then they would dip it in water and the grains would germinate." In effect, this act would tie Osirus to death, life and Earth's fertility. Or, as Javitt put it, "they're not real mummies; they're artifacts."

Face Reconstruction of Egyptian Mummies

Professional forensic artist Victoria Lywood has worked with a team of researchers to create 3D models of ancient Egyptian mummies. One model is from a mummy of the young woman from the Redpath Museum in Montreal. The woman was around 20 when she died in the A.D. 2nd century. According to Live Science: CT scans of the woman revealed that her hair was still intact and dressed in an elaborate style. hair). The information gained from the scans played an important role in reconstructing what this ancient Egyptian looked like when she was alive. [Source: Live Science, January 25, 2013]

Another key find from the scans of the young woman was that she had three punctures, about 3-4 millimeters (1/8 of an inch) in size, on the right side of her abdominal wall. These punctures could be from an event that caused her death leaving Egyptologists with a mystery — how did she get them?

Reconstruction was done on another female mummy from the Redpath Museum. Radiocarbon dating indicate that she lived late in the period of Roman rule, when Christianity was on the rise in Egypt and mummification was soon to go out of fashion. Studies of her mummy revealed her hair to be gray and it's estimated that she died between the ages of 30 and 50. She had severe dental problems including a cavity between two teeth and multiple abscesses.

The reconstruction of a young mummified man, also in the museum's collection, was done. He his twenties or early thirties and lived a few centuries earlier than the other mummies, at a time when Egypt was ruled by a dynasty of Greek kings. He had severe dental problems as well, having multiple cavities including one that caused a sinus infection, possibly killing him. CT scans show that in his last days he had linen packing, dipped in medicine, inserted into one of his cavities to try and ease his pain.

Female Egyptian Mummy Found with Tool in Her Skull

CT scans of a 2,400-year-old female mummy in 2012 revealed a tubular object embedded in its skull between the brain's left parietal bone and the resin filled back of the skull. It would turn out to be a tool used for the removal of the brain. This is only the second time that such a tool has been reported in the skull of an ancient Egyptian mummy. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, December 14, 2012]

According to Live Science: When the object was first discovered researchers were not sure what it was. So they inserted an endoscope into the mummy to get a closer look. When the endoscope clip reached the base of the object the object was cut off and brought to light for the first time in 2,400 years. The object, which measures eight centimeters (three inches) cm) in length, was cut off from resin that it had gotten stuck to (hence the jagged edge). Made of a species Monocotyledon plant, it would have been used to remove the mummy's brain. It was left in the skull by the embalmers by accident, possibly because it broke off.

The object is very brittle and researchers were limited in the forms of analysis they could do on it. When they put it under a microscope they found what are called "vascular bundles" that are each surrounded by a "dark sclerenchymatous ring," indicating it was made from a monocot plant stem of a species from the Poaceae family. This group of plants (which are very common in Egypt) includes forms of cane and bamboo. In the 5th century, Herodotus claimed embalmers used an "iron hook" to remove the brain. The new discovery suggests tools made of organic materials were also used in some cases. The woman was about age 40 when she and had suffered a fracture (that healed) in one of her hands.

CT Scans and X-Rays of Famous Egyptian Pharaohs

The mummy of Ramses the Great has Great has a shock of soft reddish-blonde hair with the texture of peach fuzz. CT scans and studies of tissue material from Ramses II’s body in the 2000s indicate that the Pharaoh had blackheads, arthritis and hardening of the arteries. X-rays of the mummy done in the 20th show he had arthritis of the hip, which forced him to stoop, and gum disease.

Research from 2014 suggests the king had a bone condition called diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis, which causes the ligaments near the spine to harden, reducing flexibility. The mummy is now at Egypt's National Museum of Egyptian Civilization. [Source: Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, July 20, 2022]

Dimitri Laboury of the University of Liège in Belgium wrote: “ Thutmose’s mummy is well preserved and allows comparison between the actual face of the king and his sculpted portraits. “On the one hand, despite a rather important evolution through different chronological types, the iconography of Thutmose III is characterized by a few absolutely constant physiognomic features, i.e., an S- shaped chin when seen in profile, a significant squared maxillary, and low, protruding cheekbones that create a horizontal depression under the eyes. These are the same features that distinguish his mummy’s face, denoting an undeniable inspiration from the actual appearance of the king. However, on the other hand, other physiognomic details varied a lot, sometimes being in obvious contradiction to the mummy: for instance, at the end of his reign, during the proscription of Hatshepsut, Thutmose III decided to straighten his nose—ostensibly hooked on his mummy—in order to look like his father and grandfather, his true and then unique legitimating ancestors. This variability and the revival of his predecessors’ iconography show that the evolution of the king’s statuary cannot be explained solely by aesthetic orientations toward portrait or ideal image, or toward realism or idealization. There is a clear and conscious departure from the model’s outer appearance that allows the introduction of meaning and physiognomically signifies the ideological identity of the depicted person. The same is true for private portraiture.

Mummy of Amenhotep I Digitally Unwrapped

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: The mummy of ancient Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep I was so exquisitely wrapped — decorated with flower garlands and buried with a lifelike face mask — scientists have been hesitant to open up the remains. That is, until now...Some 3,000 years after Amenhotep's burial, a team of researchers used CT scans to digitally unwrap his body for the first time, virtually peering through the many layers to reveal what he would've looked like when alive (he took after his dad it seems). [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, December 28, 2021]

They also found that the pharaoh, who ruled from about 1525 B.C. to 1504 B.C., was 35 years old and 5.5 feet (169 centimeters) tall when he died; he was also circumcised and had good teeth, the researchers said. Beneath the wrappings were 30 amulets as well as "a unique golden girdle with gold beads," study co-author Sahar Saleem, a radiology professor at Cairo University's faculty of medicine, said in a statement. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, December 28, 2021]

This girdle may have had "a magical meaning," and the amulets "each had a function to help the deceased king in the afterlife," Zahi Hawass, Egypt's former minister of antiquities and co-author of the new study published Tuesday (Dec. 28) in the journal Frontiers in Medicine, told Live Science in an email. "Amenhotep I's mummy is wearing a piece of jewellery called a girdle. The ancient Egyptians wore jewellery like this around their waists. Some girdles, as this one, have shell amulets on the side," Saleem told Live Science.

A team led by French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero found Amenhotep's mummy in 1881, along with several other mummies in a tomb on the west bank of Thebes (modern-day Luxor). His mummy had been placed in the tomb sometime during the 21st dynasty (around1070 B.C. to 945 B.C.) after it was robbed in ancient times. Researchers found that the robbers had damaged the pharaoh's body. "The CT images show the extent of damage of the mummy of Amenhotep I that involved neck fractures and decapitation, a large defect in the anterior abdominal wall, and disarticulation of the extremities," including the right hand and foot, wrote Saleem and Hawass in their journal article.

The researchers found that priests had repaired the mummy by placing detached limbs back in their place, using resin to help hold parts of the mummy together and rewrapping parts of the mummy with fresh bandages. "We show that at least for Amenhotep I, the priests of the 21st dynasty lovingly repaired the injuries inflicted by the tomb robbers, restored his mummy to its former glory, and preserved the magnificent jewelry and amulets in place," said Saleem in the statement.

The scans shed light on what the pharaoh looked like when he was alive. "Amenhotep I seems to have physically resembled his father [Ahmose I]: He had a narrow chin, a small narrow nose, curly hair, and mildly protruding upper teeth" said Saleem. What killed the pharaoh is unclear. "We couldn't find any wounds or disfigurement due to disease to justify the cause of death," Saleem said in the statement.

Hatshepsut’s Mummy Reveals She Was a Fat and Balding

Queen Hatshepsut was the only female to rule Egypt as a full pharaoh in a period when Egypt was strong. Often depicted as a man with a false beard, she rose to power after claiming divine birth. Her name means “the first, repeatable lady.”

Describing Hatshepsut’s mummy after it was put on display at the Egyptian Museum, Chip Brown wrote in National Geographic, “her mouth, with the upper lip shoved over the lower, was a gruesome crimp...her eye socket was packed with blind black resin, her nostrils unbecomingly plugged with tight rolls of cloth, her left ear had sunk into the flesh in the left side of her skull, and her head was almost completely without hair...The only human touch was in the bone shine of her nailed fingertips, where the mummified flesh had shrink back, creating the illusion of a manicure.”

The CT scans of Hatshepsut’s mummy also revealed that she was a fat, balding and bearded Meredith F. Small, an anthropologist at Cornell, wrote in Live Science: “Turns out, Hatshepsut...was a 50-year-old fat lady; apparently she used her power over the Upper and Lower Nile to eat well and abundantly. Archaeologists also claim that she probably had diabetes, just like many obese women today. Hatshepsut also suffered from what all women over 40 need—a stylist. She was balding in front but let the hair on the back of her head to grow really long, like an aging female Dead Head with alopecia. This Queen of Egypt also sported black and red nail polish, a rather Goth look for someone past middle age. [Source: Meredith F. Small, Live Science, July 6, 2007]

CT Scans of Tutankhamun’s Mummy

The most recent phase of scientific study of King Tutankhamun (King Tut) began in 2005, when Zahi Hawass, then the head of the Egyptian antiquities service, used the latest technologies to study Egyptian mummies. He began with CT scans on a few royals at the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, in Cairo (a.k.a. the Egyptian Museum), before driving the CT scanner to Luxor, for a test on Tut himself. [Source: Matthew Shaer, Smithsonian Magazine, December 2014 ~~]

“He found the mummy in appalling condition. It had been interred in three coffins, which sat in the sarcophagus like Russian nesting dolls. Over time, resins and ointments used in the mummification process had congealed, sealing the two inner coffins together. Carter had employed increasingly violent maneuvers to remove the mummy from the coffins, and to get at the jewelry and amulets. First, the innermost coffin was left out in the sun to roast, in the hope that the heat would melt down the resins. Next, at Carter’s suggestion, an anatomist named Douglas Derry poured hot paraffin onto the mummy’s wrappings. Later, they pried the body out and yanked various limbs apart, and used a knife to slice the burial mask away from Tut’s head. Carter later reassembled the mummy as best he could (minus the mask and jewelry), and placed it in a wooden tray lined with sand, where it would remain. ~~

Canopic jars

“Hawass was looking at a shriveled, broken thing. “It reminded me of an ancient monument lying in ruins in the sand,” he wrote. Still, he and his scientific co-workers walked the mummy, which reclined on the tray, out to the CT scanner. Hawass soon returned to Cairo with roughly 1,700 CT images of Tutankhamun. There, they were examined by Egyptian scientists and three foreign consultants: the radiologist Paul Gostner; Eduard Egarter-Vigl, a forensic pathologist; and Frank Rühli, a paleopathologist based at the University of Zurich.” ~~

See Separate Article: TUTANKHAMUN’S MUMMY: DNA, CT SCANS, DISCOVERIES africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian,AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024