Home | Category: Death and Mummies

HERODOTUS ON EMBALMING AND MUMMIFICATION

mummy bandaging

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”:“They mourn and bury the dead like this: whenever a man of note is lost to his house by death, all the women of the house daub their faces or heads with mud; then they leave the corpse in the house and roam about the city lamenting, with their garments girt around them and their breasts showing, and with them all the women of their relatives; elsewhere, the men lament, with garments girt likewise. When this is done, they take the dead body to be embalmed. 86. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

If they do the embalming in the most perfect way, they first draw out part of the brain through the nostrils with an iron hook, and inject certain drugs into the rest. Then, making a cut near the flank with a sharp knife of Ethiopian stone, they take out all the intestines, and clean the belly, rinsing it with palm wine and bruised spices; they sew it up again after filling the belly with pure ground myrrh and casia and any other spices, except frankincense. After doing this, they conceal the body for seventy days, embalmed in saltpetre; no longer time is allowed for the embalming; and when the seventy days have passed, they wash the body and wrap the whole of it in bandages of fine linen cloth, anointed with gum, which the Egyptians mostly use instead of glue; then they give the dead man back to his friends. These make a hollow wooden figure like a man, in which they enclose the corpse, shut it up, and keep it safe in a coffin-chamber, placed erect against a wall. That is how they prepare the dead in the most costly way.

“Those who want the middle way and shun the costly, they prepare as follows. The embalmers charge their syringes with cedar oil and fill the belly of the dead man with it, without making a cut or removing the intestines, but injecting the fluid through the anus and preventing it from running out; then they embalm the body for the appointed days; on the last day they drain the belly of the cedar oil which they put in before. It has such great power as to bring out with it the internal organs and intestines all dissolved; meanwhile, the flesh is eaten away by the saltpetre, and in the end nothing is left of the body but hide and bones. Then the embalmers give back the dead body with no more ado.

“The third manner of embalming, the preparation of the poorer dead, is this: they cleanse the belly with a purge, embalm the body for the seventy days and then give it back to be taken away. Wives of notable men, and women of great beauty and reputation, are not at once given to the embalmers, but only after they have been dead for three or four days; this is done to deter the embalmers from having intercourse with the women. For it is said that one was caught having intercourse with the fresh corpse of a woman, and was denounced by his fellow-workman.

“Anyone, Egyptian or foreigner, known to have been carried off by a crocodile or drowned by the river itself, must by all means be embalmed and wrapped as attractively as possible and buried in a sacred coffin by the people of the place where he is cast ashore; none of his relatives or friends may touch him, but his body is considered something more than human, and is handled and buried by the priests of the Nile themselves.”

Tia Ghose wrote in Live Science: A systematic analysis of ancient Egyptian mummy evisceration has found that historical descriptions of the techniques may have been off-base. Researchers Andrew Wade and Andrew Nelson wanted to see whether Herodotus accounts matched practices we actually see in mummies. They analyzed mummies described in the literature, and performed CT scanning on several others. They found that contrary to Herodotus' accounts, the upper and lower classes alike tended to get the trans-abdominal slit, with a cut through the anus restricted to elites. Mummies didn't show evidence of cedar oil enemas. In addition, the mummies didn't always have their hearts left in place and their brains removed. Here, a 3D reconstruction of a mummy, with an oval indicating the incision site. [Source: Tia Ghose, Live Science, March 23, 2013]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MUMMIES: HISTORY, PURPOSE, OLDEST AND SPECIAL ONES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MUMMIES AROUND THE WORLD: MUMMIFICATION, SOUTH AMERICA AND THE OLDEST ONES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MUMMY-MAKING: EMBALMING, GUIDES, HISTORY africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MUMMIFICATION WORKSHOPS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: ROOMS, EQUIPMENT AND EMBALMING INGREDIENTS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN-ERA MUMMIES: RITUALS, GOLD AND STUNNING FAIYUM PORTRAITS OF THE DEAD africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ANIMAL MUMMIES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

STUDY OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MUMMIES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MUMMY MANIA: MEDICINES, UNWRAPPING PARTIES, MOVIES africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Egyptian Mummies: Unraveling the Secrets of an Ancient Art” by Bob Brier (1994) Amazon.com;

“The Mummy Makers of Egypt” by Tamara Bower (2016) Amazon.com;

“Mummy in Ancient Egypt: Equipping the Dead for Eternity” by Salima Ikram and Aidan Dodson (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Encyclopedia of Mummies” by Bob Brier (1998) Amazon.com;

“Mummies and Death in Egypt” by Françoise Dunand (1998, 2006) Amazon.com;

“Mummies, Magic and Medicine in Ancient Egypt: Multidisciplinary Essays for Rosalie David” (2016) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Mummies and Modern Science” by Rosalie David (2008) Amazon.com;

“In Search of the Immortals: Mummies, Death and the Afterlife”

by Howard Reid (2014), mummies around the world Amazon.com;

Was Mummy-Making a Business?

The Ancient Egyptians believed, Ann R. Williams wrote in National Geographic History: To arrive in the afterlife in one piece required a preserved body. To that end, most people wished to have their corpse mummified, which preserved the body in the most lifelike state. Depending on finances, there were different degrees of mummification. The poor were simply washed and placed directly into the desert sand. Some were packed in salt to help desiccation. Those of higher status might receive an enema of juniper oil to liquefy internal organs and scent the body before salting.[Source: Ann R. Williams, October 19, 2022]

In ancient Egypt, embalmers had guild-like organizations and their methods were closely guarded secrets. "Embalming was carried out in a well-organized, institutional way," biochemist Mahmoud Bahgat of the National Research Center in Cairo, told Reuters. "They knew how to select and mix antimicrobial substances which enabled perfect skin preservation," Philipp Stockhammer of the Ludwig Maximilian University Munich said. Sticky resins were applied to make sure the bandages adhered to the body.[Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, February 2, 2023]

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: ““There are men whose sole business this is and who have this special craft. When a dead body is brought to them, they show those who brought it wooden models of corpses, painted likenesses; the most perfect way of embalming belongs, they say, to One whose name it would be impious for me to mention in treating such a matter; the second way, which they show, is less perfect than the first, and cheaper; and the third is the least costly of all. Having shown these, they ask those who brought the body in which way they desire to have it prepared. Having agreed on a price, the bearers go away, and the workmen, left alone in their place, embalm the body...The corpse is then handed over to the relatives, who enclose it in a hollow wooden coffin crafted to resemble a human which they have made for this purpose, and once the coffin is closed, they stow it away in a burial chamber." [Source: Tom Garlinghouse, Live Science, July 15, 2020] [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

Greek historian Diodorus Siculus (30–90 B.C.) traveled to Egypt and wrote about the mummification process in his book, "Library of History." Siculus said that the embalmers who performed the mummification were skilled artisans who learned the skill as a family business. He wrote that they were "considered worthy of every honor and consideration, associating with the priests and even coming and going in the temples without hindrance." He described the work of these embalmers as so meticulous that "even the hair on the eyelids and brows remains, the entire appearance of the body is unchanged, and the cast of its shape is recognizable." [Source: Tom Garlinghouse, Live Science, July 15, 2020]

Jason Treat and Ben Scott wrote in National Geographic: The business of mummification by the 26th dynasty in the 7th century B.C. was an established industry, and a costly one: Sourcing ingredients from the far reaches of the ancient world took time and money. Residues found in the discarded embalming vessels at Saqqara included many from trees and shrubs that were not native to the Nile River Delta — and, in some cases, might have originated thousands of miles away. These materials were precious: The dammar found buried in one tomb could have come from Southeast Asia. Mummification may have shaped life — and death — in ancient Egypt, but the afterlife industry that grew along the banks of the Nile likely had repercussions far and wide. Trade routes that moved people and goods over land and sea connected Egypt to other ancient civilizations. How exactly embalming ingredients reached Saqqara is not known; these routes represent likely pathways. [Source: Jason Treat and Ben Scott, National Geographic, July 10, 2023]

Prices for Mummy Services

cranial crochets used to remove the brain

Embalmers charged different rates depending in the services performed. Deluxe mummification often featured things like artificial eyes and hair extensions. For the poor, the bodies were simple allowed to dry ray and were wrapped in coarse linen bandages. Ken Johnson wrote in the New York Times, “Middle-income people had their innards liquefied by injected cedar-tree oil and drained through the rectum, also after 70 days in saltwater. The cheapest method was to give the body an enema before its 70-day immersion.”

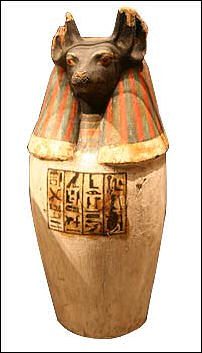

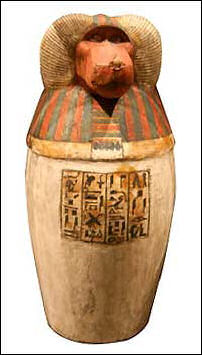

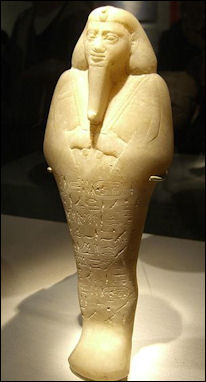

In an essay called “How Much Did a Coffin Cost — The Social and Economic Aspects of the Funerary Arts in Ancient Egypt,” the Egyptologist Kathlyn M. Cooney analyzes data to show that every element in a tomb — including the sarcophagus, canopic jars, shabties, baskets, chests and much more — had its conventional price. [Source: Ken Johnson, New York Times, March 11, 2010]

On the essay Johnson wrote in the New York Times, “A larger point made by Ms. Cooney is that contrary to the impression given by major museum collections, very few Egyptians could afford a coffin, much less a tomb and related accouterments. Because of the expense there was a thriving market in secondhand coffins, obtained most likely from grave robbers. An example in the exhibition is identified as “Coffin of the Lady of the House, Weretwahset, Reinscribed for Bensuipet” (from about 1292 to 1190 B.C.). The painted wooden container’s lid is carved in the form of a regal young woman. Examination of its hieroglyphic inscriptions proves that Bensuipet’s name was written over Weretwahset’s.” Ms. Cooney likens Egyptian funerals to modern weddings as events designed to display the power and prestige of the celebrants. Religion may have determined iconography, she notes, but “social and economic factors dictated the quality, size, materials and style of every funerary object produced in ancient Egypt.”

Mummification: a Costly, Labor-Intensive Industry?

Dr Joann Fletcher of the University of York wrote for BBC: “Certainly in Egypt mummification was very much a growth industry, with levels of service depending on cost. In the deluxe version, the brain was generally extracted down the nose and the entrails removed before the hollow body was dried out with salts. The dried skin was then treated with complex blends of oils and resins whose precise nature is now being studied using the latest analytical techniques. [Source: Dr Joann Fletcher, BBC, February 17, 2011. Fletcher is an Honorary Research Fellow at the University of York and part of the University’s Mummy Research Group |::|]

With hairdressers and beauticians called in to restore a groomed, lifelike appearance, the finished body was then wrapped in many metres of linen; one estate manager called Wah (c.2000 B.C.) had been wrapped in an amazing 375 square metres of material, although this could often be recycled household linen as well as that purpose-made for mummification. |::|

“Covered in a range of protective amulets and placed in its coffin, elaborate funeral ceremonies designed to reactivate the soul within the mummy were accompanied by the words 'You will live again for ever. Behold, you are young again for ever', before the mummy was buried with generous supplies of food, drink and everything the soul of the deceased would need for a comfortable afterlife. |::|

“The Egyptians buried their dead in the great expanses of desert away from the cultivation on the banks of the River Nile, but whereas the wealthy were artificially mummified and placed in specially built tombs, the majority were simply buried in hollows in the sand. Yet here they too were mummified by natural means, as corrosive body fluids drained away into the same hot dry sand which desiccated and preserved their skin, hair and nails. Accidentally uncovering such bodies must have had a profound effect upon those able to recognise individuals who had died sometimes years before, quite literally witnessing eternal life in action.

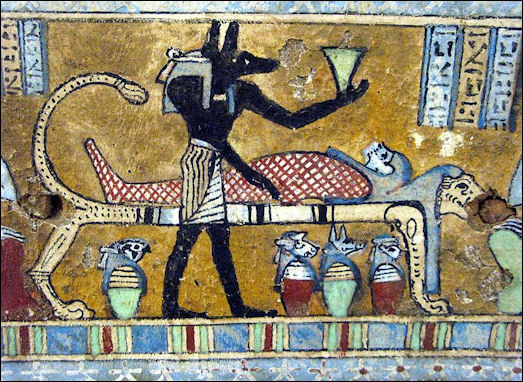

Mummy Workshops in Egypt

In May 2023, Egyptian archaeologists announced that they had discovered two workshops for mummification at the Saqqara necropolis near Cairo and the ancient city of Memphis. The workshops date to the 30th dynasty (380 to 345 B.C.) and the Ptolemaic period (305 to 30 B.C.). One of the workshops at Saqqara features stone beds meant for the preparation of human bodies, while the other has smaller beds that archaeologists think were used to mummify animals. The researchers also found instruments for mummification, clay jars for entrails, and ritual vessels for embalmed organs, as well as supplies of natron — a type of soda ash, sourced from dry lake beds in the desert, that was a key ingredient in the embalming process. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, National Geographic, December 6, 2023]

The human mummification workshop is made of mud brick and was found near Djoser's Step Pyramid, the oldest stone pyramid. It is a rectangular building divided from the inside into a number of rooms containing two embalming beds. The beds were approximately two metres long and one meter wide. They were made of stone blocks and covered with a layer of mortar that sloped down to a gutter," said Mostafa Waziri, secretary general of Egypt’s supreme council of antiquities. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, June 2, 2023; Magdy Samaan, The Telegraph, May 29, 2023]

The beds were used to embalm people. The remains of linen rolls, canopic jars, tools used to extract body organs and resin used in the embalming process were discovered inside, representatives from the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism & Antiquities said in a statement. "The mummification beds were used to prepare the body by extracting the human organs, which were placed in canopic jars that were discovered." Each bed ended in gutters to facilitate the mummification process, with a collection of clay pots nearby to hold entrails and organs, as well as a collection of instruments and ritual vessels.

See Separate Article: MUMMIFICATION WORKSHOPS AND INGREDIENTS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Mummification of King Tutankhamun

Dorothea Arnold of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The mummification of King Tutankhamun's body may have been more careful than that of his higher status subjects—and his burial was certainly immeasurably more lavishly equipped—but in essence it was not different from the embalmment of any person of reasonable means at his time. Indeed, although people of lesser means and status had to be content with only parts (sometimes very rudimentary parts) of the treatment repertoire available for kings, the difference was for the most part in the amount of time, material, and expertise expended. In principle, the mummification of a king concerned his human body, a part of his identity that he shared with all other human beings. [Source: Dorothea Arnold, Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2010, metmuseum.org \^/]

Canopic jar “After a deceased's body was washed and its organs were removed through an abdominal incision to be treated separately, the body was packed during several weeks (70 and 40 days are mentioned in the sources) in natron, a compound of sodium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, sodium sulphate, and sodium chlorite (most recently described as sodium sesquicarbonate Na2CO3.NaHCO3.2H2O), which occurs naturally in Egypt, especially in the Wadi Natrun, west of the Nile Delta. Natron is a desiccating agent. Dozens of small sacks containing natron were found in the pottery containers from KV 54. The small amount of powder contained in these bags indicates that this was most probably not the way in which the major supply of natron was delivered to the embalmers. More likely, these were bags used to stuff the body cavities during and after the dehydration process. \^/

“After the tissues were dehydrated and the body had been treated with resins, herbs, and ointments, some of which may have had antibacterial properties, linen pads, sawdust-filled linen bags, and possibly small bags with natron were placed inside the body cavities to maintain its shape. Then the long process of wrapping started. Layers upon layers of linen sheets and bandages were used to produce the characteristic figure of a mummy. \^/

“About twenty sticks, mostly reeds between 2 inches (5 cm) and 13 3/4 inches (35 cm) long, may have been used for certain probing jobs during the mummification process. Some of them have sharpened and burnt ends, raising the question whether Egyptians had a vague idea about the sterilizing effect of heat. \^/

“Since ancient times, people have wondered about the Egyptian custom of mummification. The Greek historian Herodotus, for instance, has written at length about it. According to the understanding of the ancient Egyptians themselves, the preservation of the human body was necessary so that the soul had a place on earth to which it could return in order to receive offerings and thus survive eternally. It is, however, important to realize that it was not just the preservation of the human bones and tissues that was intended. The wrapping with linen changed forever the shape of the human body and created a new being of divine character that was believed to be able to live forever.” \^/

Trash Leftover From Mummification of King Tutankhamun

Dorothea Arnold of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “In the winter of 1907–8, the young British archaeologist Edward R. Ayrton, working for the retired New York lawyer and amateur archaeologist Theodore M. Davis, discovered a pit in the Valley of the Kings about 360 feet (110 m) across from the mouth of the (then still undiscovered) tomb of Tutankhamun (KV 62). The Ayrton-Davis pit is today identified as KV 54. It had been cut in antiquity through the surface gravel covering the hillside and into the bedrock on the eastern slope bordering the Valley of the Kings. Measuring approximately 6 x 4 feet (1.90 x 1.25 m), the pit was in the 1920s still about 4 feet 6 inches (1.4 m) deep at the uphill south end and 3 feet 4 inches (1 m) at the downhill north end. Crowded into this fairly small space, Ayrton found more than a dozen gigantic pottery jars, 28 inches (71 cm) high with bulging bodies and necks.[Source: Dorothea Arnold, Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2010, metmuseum.org \^/]

“When removed from the pit, they turned out to be filled with a multitude of at first sight unintelligible objects, such as bundled-up linen sheets, bandages, and headscarves ; broken mud seals that had once been attached to strings closing boxes and bundles; sacks of various shapes containing powdery white natron and brownish sawdust; faded floral collars; and a great amount of mostly broken pots that were later joined by Metropolitan Museum conservators into whole vessels. There were also considerable amounts of animal bones and other bits and pieces such as vessel covers of reed material, sticks, and little basins of unfired clay. Rather disappointed with this discovery of what looked like scrap, Theodore Davis donated the whole lot to the fledgling Metropolitan Museum collection of Egyptian Art in 1909. \^/

Canopic jar “However, the name of King Tutankhamun on some of the mud seals and torn linens in the Ayrton-Davis pots caused knowledgeable archaeologists to take notice. Indeed, Howard Carter and Arthur Mace stated in The Tomb of TutankhAmen: Discovered by the Late Earl of Carnarvon and Howard Carter (London, 1923) that the Davis discovery had served as one of the leads by which the intact tomb of the king was finally located in 1922. \^/

“In the meantime, Herbert E. Winlock, the Metropolitan Museum's curator and long-time excavator, had discovered assemblages of rather similar objects and materials in the neighborhood of several nonroyal tombs in western Thebes. He was thus able to identify the linen sheets and bandages and sacks of chaff and natron from the large jars as leftovers from the embalming of King Tutankhamun's body. It appears that the ancient Egyptians did not simply discard the remains from the mummification process but collected them in pottery containers or coffins and buried them in the neighborhood of a deceased's tomb. This was not a simple matter of trash disposal but reflected the belief that even traces of a person's physical remains contain something of his or her identity. The objects from the Davis pit became thus a means to reconstruct some real activities that took place at a royal funeral more than 3,000 years ago. \^/

“Three especially interesting pieces found in KV 54 were most probably headscarves worn by the embalmers. They were made of very fine linen, folded double and cut to a roughly semicircular shape. Linen tapes were sewn into the straight upper edge that served as the front of the kerchief. "When being put on," Winlock wrote, "the front of these kerchiefs was probably held between the forefinger and thumb of each hand while the back was thrown up over the head, and the tapes were then carried back under the kerchief and tied." Creases along the corners show that these corners were tucked under the fastened edges above or behind the ears. Repeated laundering, wear on the fronts, and clear signs of darning indicate that these were cherished pieces of clothing that had been used repeatedly before they were buried with Tutankhamun's mummification material. The kerchief was died blue with indigo. \^/

“The German Egyptologist cum botanist Renate Germer determined from the seasonal selection of the flowers in the Museum collars and their counterpart on the king's innermost coffin that Tutankhamun's funeral took place between the end of February and mid-March. A slightly later date of March to April was advocated by Rolf Krauss.” \^/

Ancient Egyptian Mummy Preservation

The preservation of the mummies has as much to do with the dry climate of Egypt as the embalming of the mummies. The tarlike unguents used on many mummies bodies caused chemical reactions that carbonized the bones and tissues. The best preserved mummies were embalmed with dry natron salts rather than salts applied in a solution.

The exact ingredients of the embalming materials has long been a mystery. In the early 2000s, Richard Evershed at the University of Bristol in Britain took samples from 13 mummies and analyzed them using gas chromatography and mass spectrometry and found out found that most embalming concoctions were a mixture of fats, resins, perfumes and waxes.

The exact ingredients of the embalming materials has long been a mystery. In the early 2000s, Richard Evershed at the University of Bristol in Britain took samples from 13 mummies and analyzed them using gas chromatography and mass spectrometry and found out found that most embalming concoctions were a mixture of fats, resins, perfumes and waxes.

All the mummies studied by Evershed had been smeared with fat, mostly plant oils although fat from cattle, sheep and goats was also used. As the fats dried they hardened and formed a barrier that kept humidity, moisture and bacteria out. Sometimes the fats formed a shiny coating that was like varnish. They were also often coated with beeswax and resins from coniferous trees from Lebanon, Syria and Turkey

There was little evidence of palm wine, which would have evaporated away. There was no evidence of bitumen, which is ironic considering that is the material that gave mummies their name. The most probable explanation of why there was a link to the Arabic word for bitumen is that mummies blackened by age or exposure to air looked like bitumen was applied to them. Sometimes when animal mummies are being studied gases combine and the mummy explodes.

Secret of Preventing Mummy Rot: Removing the Internal Organs

Dr Joann Fletcher of the University of York wrote for BBC: “As burial practices for the wealthy became more sophisticated, those once buried in a hole in the ground demanded specially built tombs more befitting their status. Yet here they were no longer in direct contact with the sand so their bodies rapidly decomposed. This meant that an artificial means of preserving the body was required, and so began a long process of experimental mummification, and a good deal of trial and error! [Source: Dr Joann Fletcher, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Although recent excavations at the site of Hierakonpolis suggest that the Egyptians were wrapping their dead in linen as early as c.3400 B.C., with linen impregnated with resin or even plaster to retain the contours of the body used by c.3000 B.C., it wasn't until around 2600 B.C. that the Egyptians finally cracked it by removing the internal organs where putrefaction actually begins. And for the next three millennia they refined and perfected their techniques of embalming both humans and animals to become the greatest practitioners of mummification the world has ever seen.” |::|

Ancient Egyptian Mummy Objects

Nubian shabti Various object were wrapped with the mummies. These included amulets, bangles, armbands, rings and pectorals made of gold and lapis lazuli. In some cases the toes were protected with thimbles of gold. Some objects seem unlikely to be worn in real life and must have been worn by mummies only.

Many of them were amulets expected to help the mummies’ owners in the afterlife. The mysterious eye warded off evil spirits. Scarabs were associated with the rising sun and regeneration. Bird represented “ ba” , an aspect of the mummy’ soul and was thought to keep the mummy in contact with the world by flying out the burial shaft into the sunlight in the day and returning to the mummy at night.

Amulets were carried by the living and wrapped with mummies. The mummy of King Tut had 143 of them. Their primary purpose was to attract “sympathetic magic” that would protect the wearer from misfortune and maybe bring some good luck. Amulets were inserted in different stages of the embalming process, each with special spells and incantations to go along with it. Some bore inscriptions and were made of materials, such as gold, faience (a blue stone), lapis lazuli, carnelian, green feldspar, and green jasper.

Amulets with protective cobras, “ ba” (winged symbols of the soul), “ re” (sun disk), ankhs, and scarabs were popular. There were amulets for limbs, organs and other body parts and ones derived from the hieroglyphics for “good,” “truth,” and “eternity.” Hearts, hands and feet were often found on mummies in places where the real body parts were normally found, the idea being that they could be offered as substitutes if the real ones were coveted by demons.

There were amulets for at least 50 principal gods and a countless number of local ones. These amulets took the form of the gods themselves or their symbols. Popular ones included Anabus (a jackal), Horus (a falcon), Thoth (an ibis) and Hathor, the Egyptian goddess of love and fertility. The old amulets were found in simple burials dating to 3100 B.C.

The amulet symbolizing udjat (health) — the eye of Horus — connected the wearer with the god Horus, who lost his eye in a cosmic battle with the god Seth and later had the eye restored. The udjat is regarded as one of the most powerful of all amulets, preserving the wearer and making him strong in the afterlife. Tyet amulets of Isis are red in color, symbolizing her blood. They also brought strength and good health to the wearer.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024