Home | Category: Death and Mummies

MUMMY WORKSHOPS IN EGYPT

In May 2023, Egyptian archaeologists announced that they had discovered two workshops for mummification at the Saqqara necropolis near Cairo and the ancient city of Memphis. The workshops date to the 30th dynasty (380 to 345 B.C.) and the Ptolemaic period (305 to 30 B.C.). One of the workshops at Saqqara features stone beds meant for the preparation of human bodies, while the other has smaller beds that archaeologists think were used to mummify animals. The researchers also found instruments for mummification, clay jars for entrails, and ritual vessels for embalmed organs, as well as supplies of natron — a type of soda ash, sourced from dry lake beds in the desert, that was a key ingredient in the embalming process. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, National Geographic, December 6, 2023]

The human mummification workshop is made of mud brick and was found near Djoser's Step Pyramid, the oldest stone pyramid. It is a rectangular building divided from the inside into a number of rooms containing two embalming beds. The beds were approximately two metres long and one meter wide. They were made of stone blocks and covered with a layer of mortar that sloped down to a gutter," said Mostafa Waziri, secretary general of Egypt’s supreme council of antiquities. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, June 2, 2023; Magdy Samaan, The Telegraph, May 29, 2023]

The beds were used to embalm people. The remains of linen rolls, canopic jars, tools used to extract body organs and resin used in the embalming process were discovered inside, representatives from the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism & Antiquities said in a statement. "The mummification beds were used to prepare the body by extracting the human organs, which were placed in canopic jars that were discovered." Each bed ended in gutters to facilitate the mummification process, with a collection of clay pots nearby to hold entrails and organs, as well as a collection of instruments and ritual vessels.

Few mummification workshops have been found in Egypt, Ikram said. Historical texts and archaeological finds suggest that there was "probably some degree of mass production" at the animal mummification workshops, whereas human mummification workshops likely worked at a slower pace, she said. Entire families appear to have worked as embalmers, and there were probably different prices for different levels of embalming.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MUMMIES: HISTORY, PURPOSE, OLDEST AND SPECIAL ONES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MUMMIES AROUND THE WORLD: MUMMIFICATION, SOUTH AMERICA AND THE OLDEST ONES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MUMMY-MAKING: EMBALMING, GUIDES, HISTORY africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MUMMY BUSINESS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: PRICES, LABOR, WASTE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN-ERA MUMMIES: RITUALS, GOLD AND STUNNING FAIYUM PORTRAITS OF THE DEAD africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ANIMAL MUMMIES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

STUDY OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MUMMIES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MUMMY MANIA: MEDICINES, UNWRAPPING PARTIES, MOVIES africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Embalming: History, Theory, and Practice” by Sharon Gee-Mascarello (2022) Amazon.com;

“Unwrapping a Mummy: The Life, Death, and Embalming of Horemkenesi” an Ancient Egyptian Priest by John H. Taylor (1996) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Mummies: Unraveling the Secrets of an Ancient Art” by Bob Brier (1994) Amazon.com;

“The Mummy Makers of Egypt” by Tamara Bower (2016) Amazon.com;

“Mummy in Ancient Egypt: Equipping the Dead for Eternity” by Salima Ikram and Aidan Dodson (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Encyclopedia of Mummies” by Bob Brier (1998) Amazon.com;

“Mummies and Death in Egypt” by Françoise Dunand (1998, 2006) Amazon.com;

“Mummies, Magic and Medicine in Ancient Egypt: Multidisciplinary Essays for Rosalie David” (2016) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Mummies and Modern Science” by Rosalie David (2008) Amazon.com;

“In Search of the Immortals: Mummies, Death and the Afterlife”

by Howard Reid (2014), mummies around the world Amazon.com;

Underground Embalming Workshop at Saqqara

In 2016, another human mummification workshop was found near the pyramid of Unas at Saqqara. This underground facility was accessible through a 12-meters (40-foot) deep shaft and dates to Egypt's 26th dynasty, or Saite period, from 664-525 B.C., a time of Assyrian and Persian regional influence and waning Egyptian power. The facility's layout revealed the meticulousness of the embalmers, with "one room being used to clean the bodies and the other for storage [and for the actual embalming]," Susanne Beck, a lecturer in the Department of Egyptology at the University of Tübingen in Germany. The Unas underground workshop was discovered by a team led by archaeologist Ramadan Badri Hussein and is smaller than the ones discovered in 2023.

Jason Treat and Ben Scott wrote in National Geographic: The underground workshop, called a wabet, was found connected to a separate shaft over 40 feet underground. The subterranean chamber was significantly cooler than the ground above. Shafts connected to the surface kept air flowing through the chamber, freshening the room. The cooler chamber might have been used for disemboweling the body and applying oils and resins. The surface of the facility likely featured an ibu, a sacred tentlike structure used for funerary rites. Here bodies were ritually washed and bathed in natron, a mineral salt critical to the mummification process.[Source: Jason Treat and Ben Scott, National Geographic, July 10, 2023]

After being washed in the ibu, Hussein believed the body was relocated to the wabet for preparation. Embalmers used a hooked iron tool inserted into the left nostril or back of the skull to remove the brain, which was discarded. The entrails were then extracted, dried, anointed with oils and resins, and placed in special containers called canopic jars. The disemboweled body was washed and desiccated with natron for 40 days before being oiled and wrapped in linen bandages.

Multiple vessels found at Saqqara provided two valuable clues: the hieroglyphs that spelled out what the contents of each jar were used for and the residues inside that helped scientists determine ingredients through biomolecular analysis. That analysis showed that many of these mixtures were made from plants that would have been impossible to source directly from Egypt.

The main feature of the room was a sloped platform cut from stone. A carved channel allowed blood and other bodily fluids to flow to the floor. Excavators discovered a large brazier, or pan, with remnants of charcoal incense in this corner. Burning incense would have invoked the gods. It also served to keep insects away and deodorize the chamber.

Ingredients Used in a Mummy Workshop

The workshop discovered near the pyramid of Unas in Saqqara in 2016 showcased the different ingredients ancient Egyptians used for embalming. In February 2023, in an article published in Nature, archaeologists said they finally identified what many embalming ingredients were and worked out how those different ingredients — many of which came from far away places. The workshop — a complex of rooms — held approximately 100 ceramic vessels dating to the 26th dynasty of Egypt (664 to 525 B.C.). Some of the vessels had inscriptions identifying their contents. Other contained substances remained a mystery. Researchers were able to identify the contents of these using chemical analysis of the resins coating the vessels. [Source:Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, February 2, 2023]

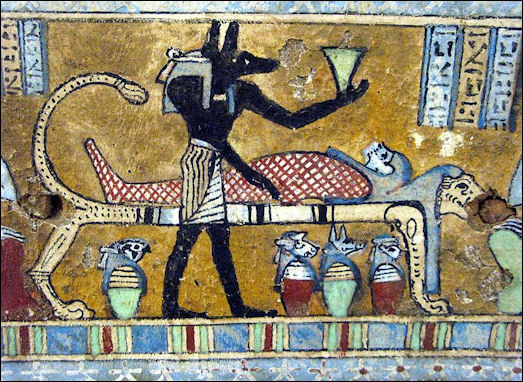

depiction of a priest during an embalming process in an underground chamber in Saqqara; Image from Nikola Nevenov

The substance labeled as "antiu" by ancient Egyptians has been translated previously as myrrh or frankincense, said Maxime Rageot, an archeologist at the University of Tübingen who oversaw the analysis. But gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis revealed the substance as a blend of cedar oil, juniper/cypress oil and animal fats, he said. [Source: Mike Snider, USA TODAY, February 2, 2023]

Jennifer Nalewicki wrote in Live Science: The researchers discovered that certain vessels were labeled with embalming instructions such as "to put on the head" or "bandage/embalm with it," while others included the names of the different substances found inside, according to a statement. But by analyzing the residues coating the pottery, they identified ingredients on 31 of the vessels coming from locations near and far. Those included resin from the elemi tree (Canarium luzonicum), which is native to the Philippines; resin from Pistacia, a genus of flowering plants in the cashew family that grow in parts of Africa and Eurasia; and beeswax.

When the researchers compared the different identified mixtures with the inscriptions on the labels, they found several inaccuracies. For one, the ancient Egyptian word "antiu," which translates to "myrrh" or "incense," was often mislabeled. In fact, none of the analyzed residues represented a single substance but rather a blend of multiple ingredients, according to the statement. "We were able to identify the true chemical makeup of each substance," study co-author Philipp Stockhammer, professor in the Department of Archaeogenetics at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, said during the conference. "Often [embalming vessels become contaminated over time], but in this case they're not. A lot of the vessels in this case were in good condition."

However, not all of the contents found in the workshop were used to preserve the dead. Instead, they likely "helped remove unpleasant smells" and prepared the bodies for embalming by "reducing moisture on the skin," study lead author Maxime Rageot, an assistant lecturer in archaeological science at the University of Tübingen, said during the news conference. "It's fascinating the chemical knowledge [the embalmers] had, since they knew bare skin would immediately be endangered by microbes," Stockhammer said. "They knew what substances were antifungal and could be applied to help stop the spread of bacteria on the skin."

Most surprising was that embalmers relied on elaborate trade networks that crisscrossed the globe to source ingredients not native to the region. "[We were] surprised to find tropical resins," Stockhammer said. "This shows that the industry of embalming was a driving trade and that ingredients were transported from large distances. What we're learning goes far beyond what we know about embalming."

Egyptian Mummies Embalmed with Substances That Smelled like Vanilla and Larch

According to Archaeology magazine: It’s difficult to imagine the myriad smells that once wafted through ancient cities. However, researchers were able to reproduce one aroma from pharaonic Egypt that has been dubbed the “scent of eternity.” By analyzing residues from canopic jars that once held the lungs and liver of a noblewoman named Senetnay, it was possible for the first time to re-create the scents of the mummification process from 3,500 years ago. The recipe included beeswax, plant oils, fats, bitumen, and various tree resins. [Source: Archaeology magazine, November 2023]

Senetnay worked as the wet nurse for the Pharaoh Amenhotep II during his infancy around 1450 B.C. Jennifer Nalewicki wrote in Live Science: Archaeologists discovered her burial in 1900 in the Valley of the Kings, a royal cemetery reserved for pharaohs and other elites. Alongside her mummy, researchers unearthed four lidded jars shaped like human heads that contained her organs, including her lungs and liver, according to a study published in August 2023 in the journal Scientific Reports. [Source: By Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science September 1, 2023

While the organs have been lost to time, two of the jars are now part of the collection at the Museum August Kestner in Germany and were available for scientists to collect samples from by scraping residue off of the pottery. After conducting chemical analysis of the swabs, researchers uncovered a complex mix of ingredients that ancient Egyptians used to create the balms, some of which weren't native to the region. "Many of the ingredients they used were unusual for that area, since they weren't readily available in ancient Egypt," lead author Barbara Huber, a doctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology in Germany, told Live Science. "They most likely acquired these ingredients through trade networks."

The balm ingredients included things like beeswax, plant oils and animal fats — all common embalming substances. But the researchers also identified coumarin and benzoic acid in the samples swiped from both jars. Coumarin is a scent similar to vanilla that's found in cinnamons and pea plants, while benzoic acid is present in resins and gums from balsam-type plants, the researchers said in a statement. In the jar used to store Senetnay's lungs, the scientists also found traces of two other exotic ingredients: larixol, a resin found in larch trees; and what they believe to be dammar, a fragrant gum from the wood of Pistacia trees. Their presence in the jars surprised the researchers because neither ingredient was growing in ancient Egypt at that time. Instead, larch trees were abundant in northern and central Europe and Pistacia trees were found across Southeast Asia, according to the study.

However, the exotic ingredients have a number of properties that would have made them attractive to ancient Egyptians. "Larch has loads of bioactive properties and is antibacterial and antimicrobial — plus it has a strong scent that can help mask decay and keep any insects away," Huber said. "It's also helpful to preserve the body in the afterlife where it can remain for an eternity. Ancient Egyptians believed that the soul could only come back if the body was intact."

The researchers noted that the ratios of the ingredients were different in both jars, but this could be the result of the "balms being unevenly mixed," Huber said. With the list of ingredients in hand, the researchers reverse-engineered the balms. Their creation was part of an exhibition at the Moesgaard Museum in Denmark in October 2023 called "Egypt Obsessed with Life."

Some Egyptian Mummification Ingredients Came From Far Away

While some of the substances – including the tar-like material bitumen – were acquired regionally, “the bulk of the substances used for embalming were not from Egypt itself," said Philipp Stockhammer, an archaeologist at the Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich, lead author of the study on the subject published in the journal Nature. [Source: Mike Snider, USA TODAY, February 2, 2023]

Many came from the eastern Mediterranean region, including cedar oil, juniper and cypress oil, and olive oil. But the resin of the elemi tree would have come from tropical Africa or Southeast Asia, he said. And dammar gum comes from trees still only found in tropical Southeast Asia.

According to Popular Science: It’s also possible this resin could have belonged to the Pistacia trees that are normally found in the Mediterranean coastal region. Additionally, there was evidence of larch resin, based on the presence of the medicinal ingredient larixol in the embalming jar. This substance, used in ancient Rome, comes from a plant species native to an area north of Egypt, across the Mediterranean. [Source: Jocelyn Solis-Moreira, Popular Science, September 1, 2023]

Stockhammer said, "This points to the fact that these resins were traded over very large distances and that Egyptian mummification was somehow a driver towards early globalization and global trade." That these substances are found in Egypt at this time in history suggests an already-established international trading network stretching from Indonesia to India through the Middle East, Mesopotamia to Egypt and to Africa, Stockhammer said. "That was already established and Egyptian embalming that requested more and more of these kinds of resins really instigated the intensification of this exchange," Stockhammer said. [Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, February 2, 2023]

Ancient Egyptian Embalming Equipment

Jason Treat and Ben Scott wrote in National Geographic: Internal organs were extracted from the body and placed in four containers, each decorated with the head of the organ’s protective god. The deities were collectively known as the Four Sons of Horus. Two canopic jars were found in the wabet and included resins used to treat the eviscerated internal organs. Bandages, called wyt or wenkhyt, were dipped in resins and fragrant oils before being wrapped around the body. A priest wearing a mask of jackal-headed Anubis, god of funerary rites, is thought have presided over the embalming. [Source: Jason Treat and Ben Scott, National Geographic, July 10, 2023]

Archaeology magazine reported: On the western side of the ancient necropolis of Abusir, a team of archaeologists led by Miroslav Bárta of Charles University has unearthed the largest cache of embalming equipment ever found in Egypt. More than 370 vessels were buried in clusters during the second half of the sixth century B.C. in a 46-foot-deep shaft, which seems to be associated with an adjacent, as-yet-unexcavated tomb. [Source: Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2022]

In the top layer of the cache, the researchers discovered four canopic jars, which were typically used to store the embalmed viscera and organs that were removed during mummification. “These jars should have been buried with the deceased in his tomb, but they were discovered clean and empty in the cache,” says Egyptologist Jiří Janák of Charles University. “We are still trying to determine whether they were copies, used only symbolically, or used for storage during the embalming process.” Inscriptions on the jars identify the deceased, Wahibre-mery-Neith, who is likely interred in the unopened tomb, and his mother, Lady Irturu. Janák suggests Wahibre-mery-Neith and Irturu may have been relatives of two individuals buried in a tomb within 165 feet of the embalming cache. He says this may be evidence that this area of Abusir was an elite family cemetery.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024