Home | Category: Death and Mummies

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN EMBALMING PROCESS

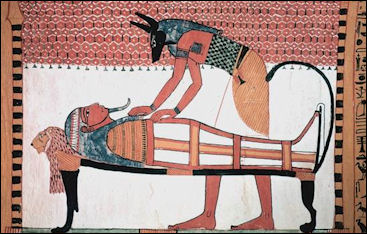

Anubis attending the

mummy of Sennedjem The embalming and mummy-making process took up to 70 days and was practiced well into the Roman period. Embalming and mummification are believed to have been carried out by a caste or family and was passed down from generation to generation. Unfortunately for historians and archaeologists no record of how they did it has survived.

Within two or three days after death all the hair was shaven off and the body was opened with special stone knives from Ethiopia. The intestines, liver and stomach were removed and placed in alabaster jars. The heart was left in place after the internal organs were removed. Sometimes the body was filled with sawdust, linen, and as well as the aromatic spices that Herodotus mentioned. Beeswax was sometimes pored in the brain cavity. Sometimes you see hair on mummies. This is not because hair keeps growing after a person dies as some have said but because dehydration of the body after death can cause retraction of the skin around hair and nails, giving the illusion that they have grown.

The body was covered in natron several days to prevent the body from decaying. The natron drew water out of the body and preserves it as if it were dried fish. Without water bacteria can not cause decay. Sometimes the tree resin of conifers was used. It too sucks out water. There are stories of the body being dried on a bed of animal heads before it is wrapped in linen.

Natron is a naturally-occurring mixture of baking soda and salt that absorbs moisture and fat. One can still buy chunks of the gray crystalline stuff in the suqs of Cairo. It is still mined in southwest of the Nile Delta and usually sold as washing soda. When it is used in mummification it gives off a strong, nasty stench. Other stuff used in mummy-making such as resinosa lumps of frankincense — which seal bandages when melted — and palm wine — which ancient embalmers used to wash out internal cavities after evisceration — are also available in the markets.

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Mummy Makers of Egypt” by Tamara Bower (2016) Amazon.com;

“Mummies, Magic and Medicine in Ancient Egypt: Multidisciplinary Essays for Rosalie David” (2016) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Mummies: Unraveling the Secrets of an Ancient Art” by Bob Brier (1994) Amazon.com;

“Mummy in Ancient Egypt: Equipping the Dead for Eternity” by Salima Ikram and Aidan Dodson (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Encyclopedia of Mummies” by Bob Brier (1998) Amazon.com;

“Mummies and Death in Egypt” by Françoise Dunand (1998, 2006) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Mummies and Modern Science” by Rosalie David (2008) Amazon.com;

“In Search of the Immortals: Mummies, Death and the Afterlife”

by Howard Reid (2014), mummies around the world Amazon.com;

Description of Embalming by Herodotus

The famous Greek historian Herodotus (c.490-c.425 B.C.) said he witnessed the embalming of a mummy on a trip to Egypt in 454 B.C. "In the best treatment," he wrote, "first they draw out the brains through the nostrils with an iron hook, and what the hook cannot reach is dissolved with drugs. Next they make a cut along the flank with a sharp Ethiopian stone, and take out the whole contents of the abdomen, which they then cleanse, washing it thoroughly with palm wine, and again frequently with an infusion of pounded aromatics. After this they fill the cavity with the purest bruised myrrh, with cassia (made from the bark of evergreen trees), and every other sort of spicery except frankincense, and sew up the opening. Then the body is placed in natrum for seventy days, and covered entirely over. [Source: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt, Fordham University]

After the expiration of that space of time, which must not be exceeded, the body is washed, and wrapped round, from head to foot, with bandages of fine linen cloth, smeared over with gum, which is used generally by the Egyptians in the place of glue, and in this state it is given back to the relations, who enclose it in a wooden case which they have had made for the purpose, shaped into the figure of a man. Then fastening the case, they place it in a sepulchral chamber, upright against the wall. Such is the most costly way of embalming the dead.

If persons wish to avoid expense, and choose the second process, the following is the method pursued: Syringes are filled with oil made from the cedar-tree, which is then, without any incision or disembowelling, injected into the abdomen. The passage by which it might be likely to return is stopped, and the body laid in natrum the prescribed number of days. At the end of the time the cedar-oil is allowed to make its escape; and such is its power that it brings with it the whole stomach and intestines in a liquid state. The natrum meanwhile has dissolved the flesh, and so nothing is left of the dead body but the skin and the bones. It is returned in this condition to the relatives, without any further trouble being bestowed upon it.

The third method of embalming, which is practised in the case of the poorer classes, is to clear out the intestines with a clyster, and let the body lie in natrum the seventy days, after which it is at once given to those who come to fetch it away.

Egyptian Mummification, 3,500 Years Ago

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: Linen used to wrap the dead in Egypt more than 6,000 years ago was permeated with a mixture of substances very similar to that used when the art of mummification was at its height 3,000 years later. Analysis of funerary wrappings that have been stored in Britain’s Bolton Museum since the 1930s has established that Egyptians cooked up recipes to mummify the dead as early as 4300 B.C. — 1,500 years earlier than previously thought. The linen wrappings came from cemeteries in the Badari region of Upper Egypt and date to well before the beginning of rule by pharaohs. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2015]

“Stephen Buckley, an archaeological chemist at the University of York, found that the wrappings were permeated with a mixture of pine resin, an aromatic plant extract, a plant gum or sugar, a plant oil or fat, and a natural petroleum source. “The recipes being used were essentially the same embalming recipes that were used 3,000 years later,” says Buckley, “when the art of mummification was at its height.” Buckley’s analysis also revealed that early Egyptians were part of a far-reaching trade network. The chemical signature of the pine oil in the embalming mixture suggests that its closest source would have been in modern-day Turkey.

Intriguingly, the earliest wrappings include chemical components typical of sea sponges. Buckley argues that sponges may have been included in the recipe because they have the ability to regenerate after a part is removed, and Egyptians likely had observed that. Rebirth was the goal of mummification in the pharaonic period, and it seems that it was in earlier times as well. “Interestingly, these early attempts at mummification only involved wrapping the head, hands, and feet. Later on, to improve preservation, it became common practice to wrap the entire body after removing the internal organs and adding natron, a salt that helped dry out the remains.

World’s Oldest Guide to Mummification — on a 3,500-Year-Old Papyrus

In 2021, scientists announced the discovery of the oldest known instructions for embalming mummies on a medical papyrus from ancient Egypt. Mindy Weisberger wrote in Live Science: How-to descriptions of the mummification process are exceptionally rare in the archaeological record — only two other such "manuals" are known. This newest example, found in an ancient scroll dating to around 1450 B.C., predates other mummification texts by more than 1,000 years. The guide contains many helpful suggestions, such as how to make herbal insect repellent and using red linen wrappings to reduce facial swelling. [Source: Mindy Weisberger, Live Science March 4, 2021

Sofie Schiødt, a research assistant in the Department of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies at the University of Copenhagen, discovered the embalming manual while translating a papyrus for her doctoral thesis, published in 2022. Half of the papyrus scroll is in the university's Papyrus Carlsberg Collection, and the other half is in the Louvre Museum in Paris. Prior to that, each piece was privately owned, and they were acquired by the university and the Louvre in 2015 and 2006, respectively, Schiødt told Live Science. It wasn't until 2018 that experts learned that the two pieces were part of the same scroll. In its entirety, the papyrus measures nearly 20 feet (6 meters) long and is inscribed on both sides. It is the second-longest medical papyrus from ancient Egypt, and Schiødt's translation project relies mostly on high-resolution photographs of the precious artifact. "This way we can move displaced fragments around digitally, as well as enhance colors to better read passages where the ink is not so well-preserved," Schiødt said. "It also aids in reading difficult signs when you can zoom in on the high-res photos."

There are five sections in the medical papyrus. In the first are short medical recipes, followed by a section on herbs. Next is a long section on skin diseases, followed by the embalming manual, "and finally another section of succinct medical recipes," Schiødt said.Only a small portion of the papyrus — just three columns of text — covers embalming. Though the mummification section is brief, it's packed with details, many of which were absent from later embalming texts."Several recipes are included in the manual describing the manufacturing of various aromatic unguents," Schiødt told Live Science, referring to substances used as ointments. However, some parts of the embalming process, such as drying the corpse with natron — a desiccating compound made of sodium carbonate and sodium bicarbonate (salt and baking soda) — aren't described at length.As such, the text reads mostly as a memory aid, helping the embalmer remember the most intricate parts of the embalming process," she said.

According to the manual, embalming a person took 70 days, and the task was performed in a special workshop near the person's grave. The two main stages — drying and wrapping — each lasted 35 days. Schiødt said that one of the exciting new pieces of information from the text involves a procedure for embalming a dead person's face. The instructions include a recipe that combines plant-based aromatics and binders, cooking them into a liquid "with which the embalmers coat a piece of red linen," she said. "The red linen is then applied to the dead person's face in order to encase it in a protective cocoon of fragrant and anti-bacterial matter," and this was repeated every four days, according to the study. On days when the embalmers were not actively treating the body, they covered it with straw infused with aromatic oils "in order to keep insects and scavengers away," according to Schiødt. Work on the mummy typically wrapped up by day 68, "after which the final days were spent on ritual activities allowing the deceased to live on in the afterlife," Schiødt wrote.

According to The Nerdist: The text “reads like a memory aid” that was intended for “specialists who needed to be reminded of these details,” rather than as an ancient step-by-step guide. Anyone using this manual would have known the basics of the embalming process already. The manual alone wouldn’t be enough to help you preserve a body in the same method. [Source: Michael Walsh, Nerdist, March 6, 2021]

Embalming and Mummification Rituals in Ancient Egypt

bandage from Tutankhamun's embalming cache

Harold Hays of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “Corresponding in length to the annual period of obscurity of the stars just south of the ecliptic, the ritualized process of embalming and mummification is usually stated as lasting seventy days. First, purification of the corpse was conducted over a period of about three days in a tent called the jbw or zH-nTr. The mummification proper was carried out in a separate structure, called the wabt, “pure place,” or pr-nfr, “good house,” of which Anubis is said to be the Hrj-sStA, “master of secrets,” therein. As a matter of decorum, representation of the ceremonial anointing and wrapping conducted there is avoided in the Pharaonic period, but the recitations accompanying these acts are attested in Roman-era papyri. The ritual instructions of these sources are late in idiom, but the recitations themselves are largely classical in phraseology. From them, one finds at the anointing that the deceased already has qualities of an akh, or exalted spirit. The Coffin Texts and “Book of the Dead” include copies of several spells for the charging and application of amulets like those discovered within mummy bindings, although these copies are often formulated as if the deceased himself is the ritualist. Since at least the New Kingdom, the preparation of the coffin was ritualized and was evidently parallel to mummification, as it also involved anointing, wrapping, and recitation. [Source: Harold Hays, Universiteit Leiden, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Since the Middle Kingdom or even earlier, the mummified corpse appears to have been the object of a set of rites associated with the night hours. In part, this Hour Vigil resumed the rites of embalming, and vignettes like that of Book of the Dead spells 1B and 151 could be understood as emblematic of this aspect of it. The god Seth, nemesis of Osiris, was warded off from the deceased, and a ritualized judgment of the dead may have been enacted during the Hour Vigil, with officiants filling the roles of the gods Isis, Nephthys, Horus, Anubis, and Thoth.

“In addition to the Hour Vigil, a set of ritual processions and voyages were conducted within the local necropolis. Just as the Hour Vigil appears to resume the events of embalming and mummification, a ritualized journey to the Delta city of Sais appears to be a re-enactment of the major funeral processions, including those to the necropolis, embalming place, and tomb. The journey to the sacred city of Abydos is regularly displayed in connection with other funerary rituals beginning in the 18th Dynasty. The point of traveling there was for the deceased himself “to ferry the god (sc. Osiris) in his ceremonies” . Notably, husband and wife are sometimes depicted together in this journey, with both described at this point as having been vindicated at the judgment of the dead (mAa xrw “true of voice”). A further and more enigmatic waterborne journey is represented in New Kingdom tombs alongside the journeys to Sais and Abydos.”

Embalming and Mummification Rituals in the Ptolemaic, Roman Periods

bronze knives used in mummification

Christina Riggs of the University of East Anglia wrote: “The Ritual of Embalming is known from two hieratic papyri with a Theban provenance, probably dating to the early first century CE. The ritual was performed by the Hry- sStA (“master of secrets,” stolist), the Xry-Hb (lector priest), and the xtmw-nTr (“divine chancellor” or seal-bearer), assisted by the wt- priests, or embalmers. The text alternates a practical instruction, such as anointing the head or wrapping the feet, with a divine invocation elucidating the action’s magical effect. The special treatment of the head, hands, and feet adduced in the Ritual of Embalming corresponds to evidence from contemporary mummies, many of which are elaborately embalmed, with anointed and gilded skin, and special wrapping or padding in the areas of the head, hands, feet, and genitals. [Source: Christina Riggs, University of East Anglia, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Common among Ptolemaic and Roman funerary texts are both lamentations and glorifications (sAxw) performed after the embalming and mummification of the dead. Lamentations and glorifications were clearly intended for recitation leading up to and surrounding the burial. In lamentation texts, family members or the goddesses Isis and Nephthys mourn and praise the deceased, while glorification texts proclaim – and thus enable – the dead person’s successful transition to a transfigured state of being. The lamentations and glorifications also make references to a vigil being kept over the body of the deceased, like the guarding of Osiris’s body recorded in the Stundenwachen texts of Ptolemaic and Roman temples. For example, two Demotic funerary papyri, Papyrus British Museum 10507 and Papyrus Harkness, contain passages that are related to the Stundenwachen spells attested in temples. Such texts may point to a similar ritual being performed for the dead, alongside the mourning rites and sAxw. The correct performance of all these rituals enabled the deceased to become like Osiris, acquiring a transfigured state among the followers of the god.

“A number of papyri, like the Rhind Papyri and the Book of Traversing Eternity, further attest to the close interrelationship between funerary rituals and temple performances by stating that the deceased will take part in temple festivals throughout the year, especially the Sokar festival during the month of Khoiak. The text on a Roman Period mummy mask refers to the rites of the Khoiak festival. Although this probably expresses an ideal, rather than an actual, day of burial, it is possible that funerary celebrations could be timed optimally to coincide with other rituals and festivities. Some papyri bear temple ritual texts that originated in the temple pr-anx (house of life, scriptorium) and were used in the cult of Osiris before they were adapted for use as private funerary papyri by the expedient of adding the deceased’s name.”

Removing the Organs from Ancient Egyptian Mummies

Canopic jars The ancient Egyptians believed that dead would use their organs in the next life and thus a great effort was made to preserve them. Embalmers removed internal organs, taking out the liver, lungs, stomach and intestines through a cut in the body and placed them in four sacred, alabaster canopic jars. Early canopic jars had human heads on them. Later ones had the heads of a human, falcon, jackal and ape. Sometime the male sexual organ was also cut off and preserved.

The internal organs were removed with minimal damage to the body through a three-inch incision made with an obsidian blade, which was considerably sharper than bronze and copper tools. The kidneys were ignored, and often left inside the body. There isn’t a word for kidney in the ancient Egyptian language. The chest, abdomen and pelvis cavities were stuffed with tightly rolled linen bundles. This was done to keep the body from collapsing.

The heart was often left in place because the Egyptians believed it was the most important aspect of the person in that it contained the intellect. Sometimes it was removed, wrapped, and placed back in the body because it was believed to be the "medium of spiritual understanding" and "the organ of thought and emotion." Egyptians believed that the heart was required for final judgement. Only if the heart was as light as the feather of truth would the god of Osiris receive its owner into the afterlife. The brain was thrown out. It had no special significance to the Egyptians.

Recreating the Organ Removal Process of Ancient Egyptian Mummies

In 1994, Bob Brier, a professor of Egyptology at Long Island University and Ronn Wade, an anatomy specialist at the University of Maryland Medical Center, attempted to replicate the embalming and mummy-making process of the ancient Egyptians — using only ancient Egyptian-era tools and Herodotus’s description — on a 187-pound Baltimore man who died of heart attack in his seventies and donated his body to science. [Sources: Wendy Marston, Discover, March 2000; Bob Brier, Archaeology, January/February 2001]

Brier and Wade used an obsidian blade to make three-inch incision for removing the internal organs and found the obsidian was sharper than a modern scalpel. The organs were then pulled through the incision, using the fingers and a copper knife. The first organs removed were the upper intestinal tract and pancreas, followed by the spleen, kidneys, and bladder. The intestines posed some difficulties because they were connected to other organs. The stomach was next, followed by the liver and lungs and the heart.

The liver was biggest obstacle and the slit had to extended to five inches to make room for it, and even then Wade said “it like delivering a small child through a tiny opening.” The heart was cut from the lungs with a bronze knife, which sharper than a copper one.

At this point the body weighed 157 pounds. When all the organs were removed, the body cavity was disinfected with palm wine and 29-linen-wrapped packets of natron were placed in the body. They absorbed water and unpleasant smells and aided dessication. The organs were placed on ceramic platters and covered with natron.

Removing the Brain from Ancient Egyptian Mummies

cranial crochets used to remove the brain

The Egyptians apparently did not appreciate the significance of the brain. After it was drawn through the nose it was thrown away and liquid resin was poured in the skull. Brier and Wade tried to remove the brain through the nose with a hook on two donated heads. Brier told Discover: “The tissue just doesn’t adhere to the tool...It’s too moist; it won’t come out. We had to put the hook and rotate it like a whisk...The brain poured out pink with a little blood, like a strawberry milk shake.”

In Archaeology Brier wrote: “We inserted a long bronze instrument shaped like a miniature harpoon, inside the naval passage and hammered it through the cribiform plate [a thin bone between the eyes] into the cranium with a wooden block. Then we inserted the coat hanger-shaped instrument into the cranium and rotated it for ten minutes on each side, breaking down the brain enough so it would run out when the cadaver was inverted.” To clean the skull they wrapped linen around a thin bronze tool and swabbed out the leftover tissue.

Materials such as mud and sand were placed in the face to prevent the head from having a shrunken appearance and make it look as lifelike as possible.

Is It a Myth That Egyptians Pulled Mummy Brains Out of the Nose

Marianne Guenot wrote in Business Insider: Contrary to what you learned in school, ancient Egyptian embalmers likely didn't pull out chunk of brains using hooks when they were preparing a dead body for the afterlife. Experiments suggest that they likely used a much more effective method, albeit one that's more unpleasant, said Stephen Buckley, an expert studying mummification. [Source: Marianne Guenot, Business Insider December 25, 2022]

Buckley, an archaeologist and analytical chemist at the University of York, told Insider he did experiments on sheep to test ways in which the brain could be removed. The work formed part of a 2008 History Channel documentary "Mummy Forensics" taking inspiration from a 1969 academic paper by British Egyptologist Filce Leek. He found that digging out the brain in chunks was not very easy. "'Hooking it out in pieces is not particularly efficient/successful," he told Insider.

It could be "slowly removed as small parts of the brain adhered to the metal hook through repeated insertions and removals", he said. But, even better "liquifying the brain makes the removal of it fairly straightforward.If you whisk the brain with a hook for about 20 minutes, the brain liquidizes and you can just pour it out," Buckley said in a later interview. It's not very nice, but that's a much more effective way of removing the brain."

There are some times when the brains were left in, Buckley said. "Particularly with the earlier, still quite well-preserved royal mummies, they actually left the brain in place in situ, so you didn't have to remove them," he said.Egyptians at that time would not have known about microbes, but they definitely understood that removing organs had a profound effect slowing the body's decay. If they could afford it, Egyptians would always have their guts, lungs, and other internal organs removed and treated to preserve them. In some cases they were put in jars, in others they were placed back in the body. The brain, however, could be left in the body to mummify inside the skull during the embalming process. For instance, Pharaoh Thutmose I, Queen Tiye, the main wife of pharaoh Amenhotep III, and Pharaoh Amenhotep I were all found with brain tissue still in place.

Ancient Egyptian Mummy-Making Process

Herodotus wrote that after the after the body was covered in natron for “70 days, never longer” the “body is washed and wrapped from head to feet in linen which has been cut into strips and smeared underside with gum, which is commonly used by the Egyptians as glue. In this condition the body is returned to the family.”

Thirty-five to 70 days after death the salt had drawn the water out of the body, which was then drained and dried. The body was washed with perfumed water and wrapped in linen soaked in preservative ointment. Prayers were said while the body was being wrapped. One such prayer went: “O doubly wonderful powerful, eternally young, and very mighty lady of the west and mistress of the east, may breathing take place in the head of the deceased in the netherworld!”

Amulets, fetishes, and pieces of papyrus with magic texts were placed with the mummy wrappings. The most important one was scarab placed on the chest. The pieces of linen was sometimes more than half a meter wide and 60 meters long. An entire mummy might be wrapped in 150 yards or more of linen. Ramses II was wrapped in about 350 yards of linen. With male mummies the penis was often separately wrapped.

Mummies from the Old Kingdom had their arms at their side. Later mummies had their arms crossed over their chest. Royals had the right arm over the left. Onions were sometimes stuffed in the eye sockets of mummies and peppers were sometimes shoved up the nose. As the embalmers became more skilled they inserted artificial eyes, golden tongues, added metal sheaths to hold the fingers in place and used resinous paste to give the corpse some color. In later dynasties the linen strips were often painted bright colors. Sometimes peppercorns were stuffed in the nose to keep it from being flattened during the wrapping.

Recreating the Mummy-Making Process

After Wade and Brier put the packets of natron in the body the placed it on a wooden platform and placed a huge bag of natron on it and placed it in a room whose temperature ranged between 90 degrees and 107 degrees F. Brier has earlier collected 580 pounds of natron from “salt fields” 60 miles outside of Cairo

After 35 days, the body was retrieved. The natron was wet and clumped around the body and smelled like “wet sand.” The body was rigid and , blackened and had shrunk from 157 pounds to 79 pounds, meaning it had lost 77 pounds of water. For all intents and purposes it was a mummy without strips of cloth.

In the next to last stage the body was rubbed with strips of linen that had been soaked in an oil containing frankincense, myrrh, cedar, lotus and palm wine. Then the body was wrapped in linen strips secured in places with a laquer made of cedar resin. The body was then left to dry out further for 140 days as opposed to 35 more as suggested by Herodotus). Afterwards it weighed 70 pounds. In the final stage the entire body was wrapped with linen, with each limb, toe and finger wrapped individually.

Five years after the mummy was made it remained virtually unchanged from the day the process was complete. There was no bacterial decay and the skin was intact.

Aufderheide has mummified a dog that was going to be put to sleep anyway and did come CT scans to spot lesions, swelling and other abnormalities that could be used in determining ailments in real mummies. Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024