Home | Category: Death and Mummies

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MUMMIES

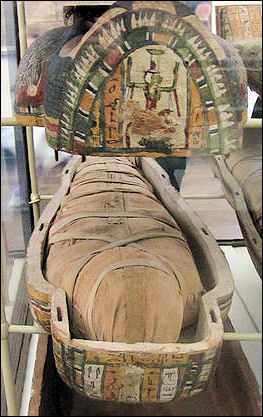

Mummies are dead bodies that went through an elaborate embalming process and then in the case of ancient Egyptians were wrapped in strips of cloth, usually linen. The Egyptian believed that if the body was preserved in a lifelike condition after death it could travel to the afterlife. Mummification was regarded as a temporary phase before eternal life. According to legend the first mummy was the god Osiris, who had been slain by his brother Seth and had his body parts scattered all over the world. Osiris’s wife Isis collected the pieces and wrapped them in linen, allowing Osiris to be reborn as the god of the dead. The word mummy is derived from “mumiya” , an Arabic word for a certain kind of bituminous asphalt found in Persia.Vultures and jackals and gods with their body parts are associated with the dead in part because they ate corpses.

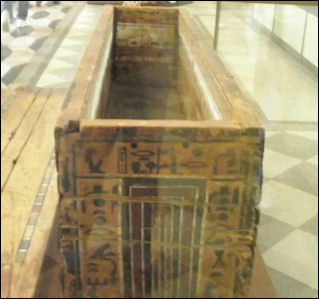

For those that could afford it death was an elaborate endeavor that involved activities that could take up to a year, not including the construction of a tomb which could take several years and which often began long before a person died. Information on funerals and burial customs comes largely from hieroglyphics on tomb walls and funeral papyri. Betsy Bryan of Johns Hopkins University told Smithsonian magazine: “People started preparing for the next world as soon as they could afford to. They bought coffins, statues when they were married and stored them in their homes. When they invited people over, everybody knew what they had and how good the quality was.”

Mummy culture is one of the most interesting and beloved features of Egyptian culture. Every schoolchild knows about them. Many kids have a deep fascination with them, some psychologists have said, partly because they discover them at a time when they first understand the significance of death. Numerous movies have been made about them. There is even a Mummy Congress, an international organization that meets once every three years to discuss mummies, the latest discoveries and research related to mummies not only from Egypt but also from the Andes, Russia, China and other places.

Generally mummies with their arms crossed are believed to be pharaohs. Those with their arms crossed lower on the body date to the period around Ramses the Great. Those with their arms crossed higher up are from a later period. Mummies can be dated by looking at the arm positions and examining the embalming and mummying techniques. Those from around the time of Ramses the Great are made of the finest linens close to the body, with slightly courser ones further out and large amounts of resin in the skull cavity. The linen is folded in a distinct way in the chest cavity.

Yuya and Tuyu are two of Egypt's best-preserved mummies. They are the parents of Amenhotep III’s Queen Tiye — and thus King Tut’s grandparents or great-grandparents. With their royal connections, the couple secured a tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MUMMIES AROUND THE WORLD: MUMMIFICATION, SOUTH AMERICA AND THE OLDEST ONES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MUMMY-MAKING: EMBALMING, GUIDES, HISTORY africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MUMMY BUSINESS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: PRICES, LABOR, WASTE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MUMMIFICATION WORKSHOPS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: ROOMS, EQUIPMENT AND EMBALMING INGREDIENTS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ROMAN-ERA MUMMIES: RITUALS, GOLD AND STUNNING FAIYUM PORTRAITS OF THE DEAD africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ANIMAL MUMMIES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

STUDY OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MUMMIES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MUMMY MANIA: MEDICINES, UNWRAPPING PARTIES, MOVIES africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

Sources: the World Mummy Congress and the Ancient Egyptian Mummy Tissue Bank at the University of Manchester in England. Dr. Arthur Aufderheide of the University of Minnesota is regarded as one of the world’s leading experts on the dissection of mummies and a founder of modern paleopathology — the study of ancient diseases.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Egyptian Mummies: Unraveling the Secrets of an Ancient Art” by Bob Brier (1994) Amazon.com;

“Tombs.Treasures.Mummies. Book Five: The Royal Mummies” by Dennis C Forbes (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Mummy Makers of Egypt” by Tamara Bower (2016) Amazon.com;

“Mummy in Ancient Egypt: Equipping the Dead for Eternity” by Salima Ikram and Aidan Dodson (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Encyclopedia of Mummies” by Bob Brier (1998) Amazon.com;

“Mummies and Death in Egypt” by Françoise Dunand (1998, 2006) Amazon.com;

“Mummies, Magic and Medicine in Ancient Egypt: Multidisciplinary Essays for Rosalie David” (2016) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Mummies and Modern Science” by Rosalie David (2008) Amazon.com;

“In Search of the Immortals: Mummies, Death and the Afterlife”

by Howard Reid (2014), mummies around the world Amazon.com;

History of Egyptian Mummification

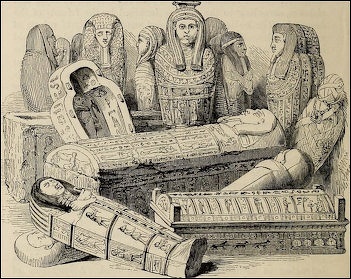

Mummy cover of a temple singer For a long time the oldest mummy was regarded a woman buried near the Great Pyramid of Cheops, dated to 2,600 B.C. (See Below) Initially only pharaohs and royalty were mummified. Later priests, high officials and aristocrats were too, and finally commoners that could afford it. For the most part mummification was simply too expensive for ordinary Egyptians. Commoners sometimes went through a perfunctory mummification. Usually they were rubbed in oil or covered in salt or tree resin and wrapped in a single sheath of linen and deposited in a hole or cave with a few possessions and amulets.

The practice of mummification reached its peak between about 1550 and 1000 B.C., during the reign of such pharaohs as Ramses II and the “boy king” Tutankhamen, better known as King Tut. “The ancient Egyptians believed the survival of the body after death was necessary in order to ‘live again’ in the afterlife and become immortal,” Stephen Buckley, an archaeological chemist at the University of York, told Reuters. “Without the preserved body, this was not possible.”

Mummification continued to be be practiced during the Greek and Roman periods in Egypt. As Christianity spread in Egypt between the second and fifth centuries A.D., the use of artificial mummification declined, according to the Royal Ontario Museum. While ancient Egyptian religion emphasized the importance of preserving the body for the afterlife, Christianity did not, the museum said. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, February 18, 2024]

The Royal Mummy Room on the top floor of the Egyptian Museum contains eleven royal mummies of pharaohs and their wives who ruled Egypt between 1552 and 1069 B.C.”including those of Ramses the Great, Seti I, Amenhotep I, and his wife Meryt-Amon. In 1981 President Anwar Sadat declared "it was undignified to display the bodies of kings" and the mummies were removed. In 1995, the mummies were once again put on display as part of campaign to boost tourism during a period when tourists were attacks by Islamists.

Purpose of Mummification

Mummification in ancient Egypt was deeply intertwined with its religious beliefs. "The ancient Egyptians were obsessed with the afterlife," said Rita Lucarelli, an Egyptologist at the University of California, Berkeley, told Live Science. "They believed that there is another life after the life here on Earth. In order for the spiritual part of the deceased to make this journey, the body needed to stay intact." [Source: Tom Garlinghouse, Live Science, July 15, 2020]

Salima Ikram, an Egyptology professor at the American University in Cairo, wrote: “The ancient Egyptians carried out mummification, the artificial preservation of the body, to ensure the survival of the body after death. They believed that the dead body could be reanimated by the ka (spiritual essence) and that the destruction of the body threatened the survival of the soul and the individual’s identity for eternity. Mummification was used primarily by elites from the early Old Kingdom on, with variations becoming available for those of lesser social and economic standing over time. The word “mummy” is derived from the Persian and Arabic word “mum”, meaning liquid pitch, asphalt, or bitumen, a substance that the Arabs mistakenly thought was used to make mummies and responsible for their dark coloring. [Source: Salima Ikram, American University of Cairo, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

Ba birds, symbols of the soul

“Egyptian funerary beliefs dictated that the body be preserved after death so that the soul— particularly the ka—could use it as a vehicle for reanimation. Without a physical manifestation (the body or images of the deceased), no aspect of the soul (ka, ba, or akh) could function in the eternal realm effectively. Mummification was the way in which the Egyptians attempted to arrest and control the decomposition of the flesh and preserve the body. The principle of mummification is very simple: it focuses on artificially dehydrating the body and preserving it with natron (a form of salt consisting of a mixture of sodium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, a small amount of sodium chloride, and traces of sodium.”

Christina Riggs of the University of East Anglia wrote: “ Encased in linen and wearing a mummy mask with tripartite wig and divine beard, the mummiform figure was no longer a human body made up of separate, movable parts. Instead, like the gods Ptah, Min, and Osiris, the saH had an undifferentiated body whose wrapped or shrouded appearance hid the articulated limbs from view. Similarly, the hieroglyphic sign for a mummiform body could mean twt, “image” or “statue.” The common assertion in Egyptological literature that the chief goal of mummification was to preserve the physical body for the afterlife may be an overstatement, or oversimplification. The process of embalming, anointing, and wrapping the corpse was essential for turning the human body into an “image” and a god-like body that transcended the mortal, physical form. The divine potential of the human body could be activated through funerary rituals and processes, such as the desiccation, anointing, and wrapping of the corpse; the incantation of prayers, hymns, and liturgies; and the performance of rites such as mourning, or the “Opening of the Mouth.” This potential has arguably been under-recognized in academic literature. [Source: Christina Riggs, University of East Anglia, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

Some Argue Ancient Egyptians Didn’t Mummify Bodies to Preserve Them?

It has long been believed that ancient Egyptians mummified the dead in order to preserve their bodies. One group of scholars claims that is not the case — rather mummification was actually a technique used to guide the deceased toward divinity. Researchers from the University of Manchester's Manchester Museum in England highlighted this idea in their 2023 exhibition "Golden Mummies of Egypt". "It's a big 180," Campbell Price, the museum's curator of Egypt and Sudan, told Live Science.

According to Business Insider the Manchester of Egyptologists argue that mummification was meant to restore the pharaoh's body to its rightful shape — the shape of a statue and that statues may have been seen as extensions of the gods on Earth. In this view, "producing a life-like image, recognizable image, actually was never the intention in the first place," but making the body look like an idealized god-like statue was, Price told Business Insider. The approach suggested that Egyptians believed kings and queens were living gods, and that turning their bodies into statues after death was a way to restore their rightful form. [Source: Marianne Guenot, Business Insider, May 5, 2023]

Marianne Guenot wrote in Business Insider: The theory goes, mummification was meant to alter the bodies in a way that didn't rely on the popular theory that the bodies would become reanimated in an afterlife. "This idea that the spirit returns to the body, or in some sense animates the body, is not as explicitly articulated as you might imagine," Price said in an interview with Insider. One of the arguments to support this theory is that mummies of some of the prominent ruling classes do not seem much concerned with preservation. King Tutankhamun's body, for instance, was found stuck to the bottom of his coffin. "It's almost as if, to read modern accounts, the mummification was botched, the ancient Egyptians didn't know what they were doing, and thus he wasn't well preserved," said Price. Under the alternate theory, "producing a lifelike image, recognizable image, actually was never the intention in the first place," Price said [Source: Marianne Guenot, Business Insider December 30, 2022]

The archaeological record suggests ancient Egyptians anointed statues of gods with oils and perfumes. They also sometimes wrapped them in linens, so it could be the bandages were thought to confer some sort of divinity."It seems that there's the world of the living and people who go about their daily lives. And then there's the world of images and representation, statues, reliefs, and paintings. That is not just an idealized version of Egypt — it's an image of gods, a kind of a statue world," Price said. By putting organs in canopic jars — jars adorned with the heads of gods — during the embalming process, Egyptians may have intended to imbue them with the godly spirit of the deceased royal, Price said, rather than keeping them handy for the afterlife.

However, not everybody agrees that the preservation aspect of mummification should be cast away. "The physical preservation of the body was extremely important. There's no question of that," Stephen Buckley, an archaeologist and analytical chemist at the University of York, told Insider. Some mummies do indeed look statue-like, such as Tutankhamun, Amenhotep III, and Akhenaten. But others, Buckley said, like Thutmose III, Thutmose IV, Amenhotep II, and Queen Tiye were mummified to look more "sleep-like," which suggests a closer concern with the physical body inside. The imagery included some imperfections, "perhaps so the soul could recognize themselves and therefore have a 'home' to return to periodically," he said. Buckley conceded that mummification was not only about preservation, but said that discounting it completely would be "to miss the point."

So how this misconception take root and continue so long? Jennifer Nalewicki wrote in Live Science, Price said the Western-led idea began with Victorian researchers who wrongly determined that ancient Egyptians were preserving their dead in a similar fashion as one would preserve fish. Their reasoning? Both processes contained a similar ingredient: salt. "The idea was that you preserve fish to eat at some future time," Price said. "So, they assumed that what was being done to the human body was the same as the treatment for fish." However, the salty substance used by ancient Egyptians differed from salt used to preserve the catch of the day. Known as natron, this naturally occurring mineral (a blend of sodium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, sodium chloride and sodium sulfate) was abundant around lake beds near the Nile and served as a key ingredient in mummification. "We also know that natron was used in temple rituals [and applied to] the statues of gods," Price said. "It was used for cleansing." [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, November 22, 2022]

Mummy-Making Much Older than Previously Thought

skeleton in the remains of a basketwork coffin, 3000 BC

It had long been thought mummification began in Egypt around 2600 B.C. but in 2014 scientists led by Stephen Buckley, an archaeological chemist at the University of York, revealed evidence that mummy-making goes back much further than that. Reuters reported: “Researchers said that a form of mummification was being carried out in Egypt more than 6,000 years ago. They said embalming substances in cloth used to wrap bodies from the oldest-known Egyptian cemeteries showed mummy-making from as early as about 4300 B.C. Linen used to wrap the dead bodies was soaked with the embalming agents to protect them from bacteria. The process was being used more than 1,500 years earlier than Egyptian mummification had been thought to have started. The discovery was found by studying burial cloths retrieved from cemeteries in the 1920s and 1930s and held in Britain’s Bolton Museum. [Source: Reuters, August 16, 2014 ^]

Several mummies that are more than 5,000 years old were found at the site of Gebelein, about 25 miles (40 kilometers) south of ancient Thebes (modern-day Luxor). The oldest known Egyptian mummy that was naturally preserved dates to just over 5,500 years ago, Live Science reported. That mummy was of a young woman whose body was wrapped in linen and fur after she died. [Source: Tom Garlinghouse, Live Science, July 15, 2020]

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: The earliest evidence of mummies in Egypt includes 6,300 year-old mummy wrappings that were found at an ancient Egyptian cemetery at the site of Mostagedda, about 200 miles (320 kilometers) south of Cairo. The burials were excavated in the early 20th century, and the wrappings were brought to the U.K. and are now in the Bolton Museum as Buckley and colleagues noted in the PLOS One study in 2014. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, February 18, 2024]

In the study, the scientists tested the wrappings and found that they contain resins typically used in mummification. The tests indicate that these resins were made from a variety of ingredients such as plant oil, animal fats, wax and plant gum. Similar resins were also used in later time periods by the ancient Egyptians for mummification, the scientists noted. To put the 4,300 B.C. date into context, this is about a millennium before the Egyptians developed hieroglyphs and about 1,500 years before they started building pyramids. It is also about a millennium before Egypt became unified under a single pharaoh.

While the oldest evidence for using artificial means to mummify bodies dates back around 4,300 B.C., Egyptians underwent natural mummification in even earlier times. Natural mummification "is an accidental process caused by favorable burial conditions," such as being buried in hot, dry sand, Buckley said. "The Egyptians didn't start to naturally mummify their dead at any point in time in terms of a conscious act," Buckley said.

Ancient Egyptian Proto-Mummies

The bodies of two women, dated around 3500 B.C., found in a cemetery used by working class people in the site of Hierakonoplis, bear evidence of mummification: parts of their body had been padded with linen bundles and wrapped in resin-soaked linen bandages. Other bodies from this period appear to have been ritually beheaded. Excavations there uncovered the tomb of elephant covered in fine fabrics and oriented to the west like humans. A wrapped arm was found in the tomb of the First Dynasty King Den (circa 2980 B.C.)

Old Kingdom (2686 to 2125 B.C.) proto mummies consisted of defleshed bones with features plastered on them. Each bone was wrapped separately in linen; then the body was assembled. The wrapping was done with great care. Linen was wrapped inside the kneecaps, around each finger joint, and in and out of individual vertebrae. The eye sockets had been filled with balls of paste pressed into linen. The penis was carefully modeled in linen.

Old Kingdom (2686 to 2125 B.C.) proto mummies were first discovered in 1910 by archaeologist W.M. Flinders near where he found an Old Kingdom pyramid text read: "Take you head, collect your bones, gather your limbs, shake the earth from your flesh!...The gatekeeper comes out for you, he grasps your hand, takes you into Heaven."

Some archaeologists believe that the ancient Egyptians and other people that practiced mummification may have been inspired by the natural preservation that takes place when a body is buried in hot desert sand and has its water drawn out, leaving behind an intact body that seems like a better home for a spirit than decayed flesh and bones.

Evidence of Advanced Mummy Embalming From 4,400 Years Old

In 2021, archaeologists announced that a Egyptian mummy embalmed with advanced techniques is believed to be much older than initially thought. Business Insider reported: “The discovery suggests sophisticated mummification skills were used 1,000 years earlier than previously believed, with experts saying it could "turn our understanding of the evolution of mummification on its head." Khuwy's ornate tomb featured hieroglyphics that suggested the burial took place during the Fifth Dynasty period, spanning the early 25th to mid-24th century B.C., The Smithsonian said. [Source: Alia Shoaib, Business Insider, October 30, 2021]

“The discovery centers around a mummy, known as Khuwy, believed to have been a high-ranking nobleman. He was excavated at the necropolis, a vast ancient burial ground of Egyptian pharaohs and royals near Cairo, in 2019. Scientists now believe that Khuwy dates back to Egypt's Old Kingdom (2,700 to 2,200 B.C.), which would make him one of the oldest Egyptian mummies ever to be discovered, The Observer reported.

“Khuwy was embalmed using advanced techniques thought to have been developed much later.His skin was preserved using expensive resins made from tree sap, and his body was impregnated with resins and bound with high-quality linen dressings. The new analysis suggests that ancient Egyptians living around 4,000 years ago were carrying out sophisticated burials. "This would completely turn our understanding of the evolution of mummification on its head," Professor Salima Ikram, head of Egyptology at the American University in Cairo, told The Observer. "Until now, we had thought that Old Kingdom mummification was relatively simple, with basic desiccation — not always successful — no removal of the brain, and only occasional removal of the internal organs," Ikram told The Observer.

“Ikram was surprised by the amount of resin used to preserve the mummy, which is not often recorded in mummies from the Old Kingdom. She added that typically more attention was paid to the exterior appearance of the deceased than the interior. "This mummy is awash with resins and textiles and gives a completely different impression of mummification. In fact, it is more like mummies found 1,000 years later," she said. Ikram told The National that the resin used would have been imported from the Near East, most likely Lebanon, demonstrating that trade with neighboring empires around that time was more extensive than previously thought.

4,300-Year-Old Golden Mummy

In January 2023, archaeologists in Egypt announced that they had uncovered a series of tombs dating back around 4,300 years at Saqqara, including a sarcophagus holding the oldest known ancient Egyptian mummy that is covered with gold. Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: The record-breaking tomb had a sealed sarcophagus containing the mummy of a man that a hieroglyphic inscription identifies as Hekashepes, and whose remains were found covered with gold. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, February 1, 2023]

."When the sarcophagus was examined, it was found to be completely sealed with mortar, just as the ancient Egyptians had left it 4300 years ago. When the lid was raised, we found the mummy of a man covered with gold leaf," the team said in a statement posted on the Facebook page of Zahi Hawass, a former minister of antiquities who led the team that made the discoveries. However, while other news outlets are reporting that this is the oldest Egyptian mummy known to archaeologists, that's not the case. Rather, "This mummy is the oldest complete mummy covered with gold," Hawass told Live Science.

There is little information about Hekashepes, but it appears that "he was wealthy," Hawass said. Hekashepes' mummy was mummified using artificial methods, is intact and is covered with gold. According to images posted online of Hekashepes' remains, it appears that his mummy is wearing clothes and doesn't have bandages, Francesco Tiradritti, an Egyptology professor at the Kore University of Enna in Italy who was not involved with these excavations, told Live Science. The deceased seems like he was buried wearing a tunic with a belt and large necklace. This may be an attempt "to preserve as much as the living appearance of the deceased," Triadritti said, something that might shine light on religious beliefs at the time this man died.

Screaming Mummy May Have Experienced an Agonizing Death

In August 2024, Reuters reported: It is a startling image from ancient Egypt — a mummy discovered during a 1935 archaeological expedition at Deir el-Bahari near Luxor of a woman with her mouth wide open in what looks like an anguished shriek. Scientists now have an explanation for the "Screaming Woman" mummy after using CT scans to perform a "virtual dissection." It turns out she may have died in agony and experienced a rare form of muscular stiffening, called a cadaveric spasm, that occurs at the moment of death. [Source Will Dunham, Reuters, August 2, 2024]

The examination indicated that the woman was about 48 years old when she died, had lived with mild arthritis of the spine and had lost some teeth, said Cairo University radiology professor Sahar Saleem, who led the study published August 2, 2024 in the journal Frontiers in Medicine. Her body was well-preserved, being embalmed roughly 3,500 years ago during the New Kingdom period using costly imported ingredients such as juniper oil and frankincense resin, Saleem added.

It was customary during the mummification process to remove the internal organs, aside from the heart, but this had not occurred with this woman. "In ancient Egypt, the embalmers took care of the dead body so it would look beautiful for the afterlife. That's why they were keen to close the mouth of the dead by tying the jaw to the head to prevent the normal postmortem jaw drop," Saleem said.

But the quality of the embalmment ingredients "ruled out that the mummification process had been careless and that the embalmers had simply neglected to close her mouth. In fact, they mummified her well and gave her expensive funerary apparels — two expensive rings made of gold and silver and a long haired-wig made from fibers from the date palm," Saleem added. "This opened the way to other explanations of the widely opened mouth — that the woman died screaming from agony or pain and that the muscles of the face contracted to preserve this appearance at the time of death due to cadaveric spasm," Saleem said. "The true history or circumstances of the death of this woman are unknown, hence the cause of her screaming facial appearance cannot be established with certainty."

Cadaveric spasm, a poorly understood condition, occurs after severe physical or emotional suffering, with the contracted muscles becoming rigid immediately following death, Saleem said. "Unlike postmortem rigor mortis, cadaveric spasm affects only one group of muscles, not the entire body," Saleem added. Asked whether the woman may have been embalmed while alive, Saleem added, "I don't believe that this is possible." Saleem was unable to determine how the woman died, saying, "We frequently cannot determine the cause of death in a mummy unless there is CT evidence of fatal trauma." Saleem cited evidence of a fatal head injury, slit neck and heart disease in three royal mummies.

The "Screaming Woman" was found at the site of the ancient city of Thebes during excavation of the tomb of a high-ranking official named Senmut, the architect, overseer of royal works and reputed lover of queen Hatshepsut, who reigned from 1479-1458 BC. The mummy was inside a wooden coffin in a burial chamber beneath Senmut's family tomb. Her identity has not been determined but her jewelry — the gold and silver rings with images of scarab beetles, a symbol of resurrection, made of the gemstone jasper — showed her socioeconomic status. "She was likely a close family member to be buried and share the family's eternal resting place," Saleem said. The study revealed details of her wig. Its spiral braids were treated with the minerals quartz, magnetite and albite to harden them and provide the black color indicative of youth. Her natural hair had been dyed with henna and juniper oil.

A number of ancient mummies, in Egypt and the Americas, have been found with facial expressions resembling a scream — eerily similar to Norwegian painter Edvard Munch's "The Scream." "I use this painting in my public lectures about the screaming mummies," Saleem said.

Fetus Mummy: Youngest and Smallest Ancient Egyptian Mummy Ever Found

Sarcophagus with a mummy In 2016, scientists announced the discovery of a fetus mummy said to be youngest and smallest Ancient Egyptian human mummy ever found. Elahe Izad wrote in the Washington Post: “British archaeologists dug up the tiny coffin in Giza, Egypt, nearly 100 years ago, and it's sat in a Cambridge museum ever since. For decades, researchers thought the small bundle inside was nothing more than a bunch of mummified internal organs, the sort of gruesome thing you end up with after a routine adult embalming. But new CT-scans show the remains are actually that of a fetus, the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge said. [Source: Elahe Izadi, Washington Post, May 12, 2016]

“The fetus is the first "academically verified" Egyptian mummy found to exist at 16 to 18 weeks of gestation, according to the museum. Julie Dawson, head of conservation at the museum, called the mummy an "extraordinary archaeological find that has provided us with striking evidence of how an unborn child might be viewed in ancient Egyptian society." The care taken in the preparation of this burial clearly demonstrates the value placed on life even in the first weeks of its inception," Dawson said.

“Researchers believe this fetus was likely the result of a miscarriage. Other mummified ancient Egyptian fetuses have been discovered, but they have been older. Two mummified fetuses, likely 25 to 37 weeks old, were found in individual coffins within King Tut's tomb. This newly discovered mummy likely dates to between 664 and 525 B.C., according to the Fitzwilliam Museum. The package inside of the 17-inch-long, deteriorated cedar coffin had been carefully wrapped and bound with bandages and then covered in molten black resin.

“Initially, efforts to X-ray the contents of the coffin yielded inconclusive results. But during preparations for an upcoming exhibition on ancient Egyptian practices regarding death, the museum decided to have another look. The coffin was re-examined at Cambridge University's Department of Zoology — this time with micro CT-scanning. "The cross-sectional images this produced gave the first pictures of the remains of a tiny human body held within the wrappings, which remain undisturbed," the museum said in a statement. Scans clearly showed five fingers on both hands, five toes on both feet and long arm and leg bones. The fetus had its arms crossed over its chest, which, "coupled with the intricacy of the tiny coffin and its decoration, are clear indications of the importance and time given to this burial in Egyptian society," reads a statement from the museum.”

Mummies of Commoners

In 2019, Archaeology magazine reported: Thirty-six mummies dating to between 600 B.C. and A.D. 100 have been discovered by a team of Polish archaeologists in Saqqara, the ancient cemetery of the city of Memphis in Egypt. These mummies received only the simplest embalming, explains excavation director Kamil Kuraszkiewicz, an Egyptologist at the University of Warsaw. “There are no inscriptions or personal items that would hint at these people’s names or professions,” he says, “but analysis of skeletal remains indicates that they mostly performed hard labor.” Of the very few coffins found with the mummies, one was decorated with a nonsensical hieroglyphic inscription and rough depictions of jackals meant to represent Anubis, the god of death. The designs seem to imitate coffins found in high-status burials. [Source: Zach Zorich, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2019]

Ikram told Live Science that the earliest examples of naturally mummified mummies date from 5000 B.C. if not earlier. Even after artificial mummification was developed, many Egyptians were still naturally mummified because they were unable to afford artificial mummification and so were buried in the desert. The "majority of ancient Egyptians were simply put in a hole in the ground, with no preparation" and could accidentally become naturally mummified, Buckley said. Ikram said that "we don't know what was in the minds of the ancient Egyptians. But, whomever was put into a sandy grave, far from water, and not enclosed with a reed mat/coffin or in a skin, would have been naturally mummified."

On embalming he said he witnessed on a trip to Egypt in 454 B.C., the famous Greek historian Herodotus (c.490-c.425 B.C.) wrote: If persons wish to avoid expense, and choose the second process, the following is the method pursued: Syringes are filled with oil made from the cedar-tree, which is then, without any incision or disembowelling, injected into the abdomen. The passage by which it might be likely to return is stopped, and the body laid in natrum the prescribed number of days. At the end of the time the cedar-oil is allowed to make its escape; and such is its power that it brings with it the whole stomach and intestines in a liquid state. The natrum meanwhile has dissolved the flesh, and so nothing is left of the dead body but the skin and the bones. It is returned in this condition to the relatives, without any further trouble being bestowed upon it. The third method of embalming, which is practised in the case of the poorer classes, is to clear out the intestines with a clyster, and let the body lie in natrum the seventy days, after which it is at once given to those who come to fetch it away.

60 Mummies in Tomb of the Warriors Died 'Bloody, Fearsome Deaths'

mummy case About 4,200 years ago, 60 men who died of terrible wounds were mummified and entombed together at the Tomb of the Warriors in the cliffs of Deir el Bahari near Luxor. Mass burials were exceptionally rare in ancient Egypt — so why did all these mummies end up in the same place? In 2018, researchers under Salima Ikram, a professor of Egyptology at the American University in Cairo, visited the tomb. According to Live Science: After analyzing evidence from the tomb and other sites in Egypt, they pieced together the story of a desperate and bloody chapter in Egypt's history at the close of the Old Kingdom, around 2150 B.C. [Source: Mindy Weisberger, Live Science, April 5, 2019]

Their findings, presented in the PBS documentary "Secrets of the Dead: Egypt's Darkest Hour," paint a grim picture of civil unrest that sparked bloody battles between regional governors about 4,200 years ago. One of those skirmishes may have ended the lives of 60 men whose bodies were mummified in the mass burial, PBS representatives said in a statement.

From the tomb's entrance, a maze of tunnels branched out about 200 feet (61 meters) into the cliff; chambers were filled with mummified body parts and piles of bandages that had once been wrapped around the corpses but had come unraveled, Ikram discovered. The bodies all seemed to belong to men, and many showed signs of severe trauma. Skulls were broken or pierced — probably the result of projectiles or weapons — and arrows were embedded in many of the bodies, suggesting the men were soldiers who died in battle. One of the mummies was even wearing a protective gauntlet on its arm, such as those worn by archers, according to Ikram. "These people have died bloody, fearsome deaths," Ikram said. Evidence from elsewhere in Egypt suggests that they died during a period of extreme social upheaval.

World’s First Pregnant Ancient Egyptian Mummy?

In April 2021, researchers from the Warsaw Mummy Project in Poland released a paper announcing the discovery of the first known pregnant mummy, which they called the Mysterious Lady. The mummy, which dates back to the first century B.C., was found inside a coffin thought to belong to a male Egyptian priest, but X-ray and CT scans of the mummy revealed that the remains belonged to a female. The scans also highlighted a structure in the mummy's abdomen that the researchers believed to be a fetus, which they estimated was around 28 weeks old. [Source: Harry Baker, Live Science, January 27, 2022]

In a study published in January 2022, carried out by the same Polish team, researchers focused on explaining why the fetus had no skeletal bones nor a defined body shape. The Polish team proposed that the mom's uterus would have become acidic over time due to the mummification process and that acidity would have slowly dissolved the fetus's bones, leaving behind a deformed lump of mineralized tissue seen in the mummy scans. The researchers said the process that destroyed the fetus is similar to how an egg might be pickled. "It is not the most aesthetic comparison, but conveys the idea," the team wrote in a blog post.

The Polish team's new proposal is based on the idea that the human body becomes more acidic (or has a lower pH) as it decomposes. Without oxygen input in the body, the chemical reactions that occur produce acidic compounds, such as formic acid. "Blood pH in corpses, including content of the uterus, falls significantly, becoming more acidic," the researchers wrote.The researchers said the acidification process is more severe in mummies because natron, a naturally occurring salt that was packed in and around the body during the mummification process, creates a barrier that traps the acid inside certain places, such as the uterus. "The end result is an almost hermetically sealed uterus containing the fetus," the researchers wrote.

The research team published this study in response to criticism of their initial 2021 paper describing the discovery of the Mysterious Lady. The study's main critic was Sahar Saleem, a mummy expert and professor of radiology at Cairo University in Egypt. Saleem was skeptical that the fetus was legitimate because of a lack of physical evidence, such as bones. And, despite the new paper, Saleem remains unconvinced and questions whether the mummy was pregnant. "In their response, the Polish team failed to address my concerns or identify any evidence of anatomical structures to justify their claim of a fetus," Saleem told Live Science. She thinks that the pickling theory only explains why there is no sufficient physical evidence of the fetus and that it does not provide any additional proof that the structure is a fetus at all.

The acidic conditions inside the mummy's uterus would not have been strong enough to dissolve fully formed human bones. However, they could have dissolved fetal bones because "mineralization [of bones] is very weak during the first two trimesters of pregnancy and accelerates later," the researchers wrote. However, the rest of the soft tissues making up the fetus would have stayed largely intact.

Nor does the new paper explain why the uterus and alleged fetus were left inside the mummy in the first place. That would have been very unusual in ancient Egypt, where removing such structures and organs was part of the mummification process, Saleem said. If the body had become acidic enough to start dissolving the fetus's bones, the rest of the mummy's body, in particular its bones, would not have been so well preserved, she added.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian,AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024