Home | Category: Late Dynasties, Persians, Nubians, Ptolemies, Cleopatra, Greeks and Romans / Death and Mummies / Art and Architecture

ROMANIZED MUMMIES

Mummy found in the Valley of the Golden Mummies, now in el-Bawiti museum, el-Bahriya, Libyan desert, Egypt

Egyptians continued to be embalmed, mummified and laid to rest in Egyptian-style tombs during the periods when Ptolemic Greeks and Romans occupied Egypt. The mummies and their tombs showed Egyptian, Greek and Roman influences. The practice of mummification began to disappear around the A.D. 4th century when Christianity began to flourish.

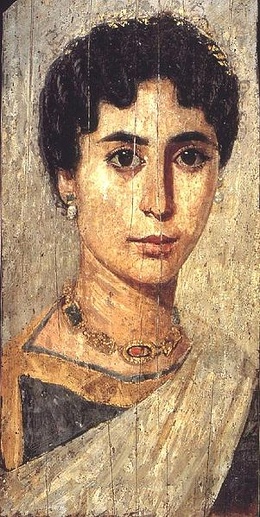

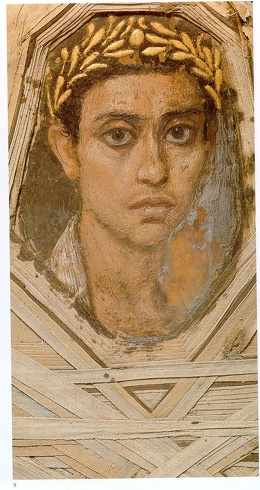

Romanized Egyptians often but more work into the exterior decorations of the mummy coverings than on the mummification process. The dead were embalmed and wrapped as mummies. Painted portraits of the deceased were made on shrouds wrapped around the mummy wrappings. The portraits were sometimes quite beautiful and realistic. They were painted on linen and plaster. Sometimes they were covered with gold.

Mummification was performed on ordinary people but the work was shoddy compared to what was done for pharaohs and noblemen in Pharonic times. The mummification process was done in 40 days instead of 70, there were no canopic jars for organs, and many mummies were buried with coffins or sarcophagi.

The mummies had Roman hairstyles and held Greek or Roman coins used to bribe the ferryman in the other world the but the iconography on the masks and painted deities that showed the way to the afterlife were clearly Egyptian.

RELATED ARTICLES:

STUNNING, ROMAN-ERA, FAIYUM MUMMY PORTRAITS europe.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MUMMIES: HISTORY, PURPOSE, OLDEST AND SPECIAL ONES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MUMMIES AROUND THE WORLD: MUMMIFICATION, SOUTH AMERICA, THE OLDEST ONES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MUMMY-MAKING: EMBALMING, GUIDES, HISTORY africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MUMMY BUSINESS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: PRICES, LABOR, WASTE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MUMMIFICATION WORKSHOPS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: ROOMS, EQUIPMENT AND EMBALMING INGREDIENTS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ANIMAL MUMMIES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

STUDY OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN MUMMIES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MUMMY MANIA: MEDICINES, UNWRAPPING PARTIES, MOVIES africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Golden Mummies of Egypt: Interpreting Identities from the Graeco-Roman Period”

by Campbell Price and Julia Thorne (2023) Amazon.com;

“Mysterious Fayum Portraits” by Euphrosyne Doxiadis (1995, 2025) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Faces: Mummy Portraits from Roman Egypt” by Susan Walker (1997) Amazon.com;

"Mummy Portraits in the J. Paul Getty Museum" (Oxford University Press, 1982).

Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Mummies: Unraveling the Secrets of an Ancient Art” by Bob Brier (1994) Amazon.com;

“The Mummy Makers of Egypt” by Tamara Bower (2016) Amazon.com;

“Mummy in Ancient Egypt: Equipping the Dead for Eternity” by Salima Ikram and Aidan Dodson (1999) Amazon.com;

“Mummies and Death in Egypt” by Françoise Dunand (1998, 2006) Amazon.com;

“Mummies, Magic and Medicine in Ancient Egypt: Multidisciplinary Essays for Rosalie David” (2016) Amazon.com;

“In Search of the Immortals: Mummies, Death and the Afterlife”

by Howard Reid (2014), mummies around the world Amazon.com;

“Roman Egypt” by Roger S. Bagnall (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Roman Egypt” by Christina Riggs (2020) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Greco-Roman and Late Antique Egypt” by Katelijn Vandorpe (2019) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Roman Egypt” by David Frankfurter (2000) Amazon.com;

Funerary Rituals During the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods

Christina Riggs of the University of East Anglia wrote: “Ancient Egyptian rituals for the mummification, burial, and commemoration of the dead are attested by textual sources and visual arts from the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, as well as the evidence of mummified bodies. Some rituals have clear antecedents in Dynastic Egypt. Other rituals, in particular the Ritual of Embalming, are known only from Ptolemaic and Roman source material but almost certainly derive from earlier practices for which comparable evidence is lacking. A number of the textual sources are known by versions of their ancient Egyptian titles, such as the Book of Breathing made by Isis for her brother Osiris. However, long compositions on multiple-column papyri often include several “types” of texts, mostly without titles. Although these text “types” can be identified by comparing their content and form with titled examples, this is only a tool of scholarly classification. To the ancient Egyptians, such distinctions may well have been meaningless, and the combination of several text “types” on one papyrus may imply that they were performed together in a ritual context, though this can never be known with certainty. [Source: Christina Riggs, University of East Anglia, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“During the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, new funerary compositions include the Book of Breathing, the Book of Traversing Eternity, and the Book of the Ba. These compositions gradually supplant the Book of the Dead, the last dated example of which is a copy of BD Chapter 125 inscribed with an excerpt from the Book of Traversing Eternity on a papyrus from CE 64. Regional variation was an important factor in the exact forms that ritual texts took, and the script in which they were written – Demotic at Akhmim, for instance, and bilingual Demotic and hieratic at Thebes. The function of all these books is similar, however: they commemorate the deceased within his or her social group, and secure a good burial, effective transfiguration, and successful rebirth in the afterlife. Another innovation of the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods is that the texts address at length how the deceased’s akh will participate in festivals throughout Egypt, listing major cult sites such as Thebes and Bubastis.

“Any or all such texts can be considered to have a ritual character effected through oral recitation and performance. Some scholars, though, distinguish between “funerary literature” written down and deposited with the body, without performance, which was meant for use by the deceased, and “mortuary liturgy,” referring to texts that survive in written form but were intended to serve as scripts for ritual performance by the living for the benefit of the deceased. Like debates over the titles and typologies of texts, this distinction may reflect scholarly convenience rather than ancient practice, and Baines argues that it is not possible or meaningful to differentiate between “literature” and “liturgy.” Certainly the performance of ritual actions and processions was central to how Egyptians expressed the wish for an ideal burial: “All the rites will be carried out for you by the Xry-Hb (lector priest, Greek taricheutes) at the place of justification, and every procession up to your time” (Papyrus Rhind II, 3 h 3). Continuity, innovation, and regional variation thus characterize trends in both the textual evidence for funerary rituals and the pictorial and material remains associated with ritual performances, such as mummy and tomb decoration. Although there are distinctive traits and developments in the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, shaped in part by wider social trends, funerary rituals retain many of the themes, structures, and practices of earlier periods, and may have been more resistant to change than other areas of Egyptian culture.

“Artistic evidence from tombs, coffins, and mummy masks confirms the central role of ritual performance in the mortuary sphere. Funeral processions featuring sem-priests and lector priests feature in the fourth century B.C. Tomb of Petosiris at Tuna el-Gebel, as well as the Roman Period tomb of a woman or girl (House 21) nearby. In Dakhla Oasis, the first century CE Tomb of Petubastis also depicts an extensive burial procession. The Petosiris funeral scene at Tuna el-Gebel includes the purification of the mummy in front of a pyramid-topped tomb, derived from Dynastic depictions of the Opening of the Mouth ceremony. Processions of deities carry linen and ointments for the mummification of the dead, for instance on a group of first century CE mummy masks from Meir. Decorated and inscribed linen amulets would have been part of the mummification ritual, mirroring the depiction of such wrappings in the Osiris chapels of Ptolemaic and Roman temples and the identification of the dead with Osiris. Similarly, the depiction of the Sokar barque on a group of third century CE masks from Deir el-Bahri may invoke the Khoiak festival.”

Mortuary Service and Opening of the Mouth in the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods

Christina Riggs of the University of East Anglia wrote: “Other ritual texts were composed for performance on the day of burial, sometimes in conjunction with the celebration of a funerary meal. One section of a late Ptolemaic papyrus in Demotic is entitled, “The book which was made in exact accordance with his desire for Hor, the son of Petemin, to cause it to be recited as an Opening of the Mouth document in his presence on the night of his burial feast,” which points to continuity with the Pharaonic Opening of the Mouth ritual performed on the deceased’s mummy at the tomb. P. BM 10507 is also of interest for the fact that it ascribes agency to the deceased himself in the selection and composition of the text. This particular papyrus comes from late Ptolemaic or early Roman Akhmim, where priestly families among the local elite may have been more likely to be buried with such papyri, ritual care, and high quality burial goods. [Source: Christina Riggs, University of East Anglia, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Another Demotic text, Papyrus Harkness, includes a section headed, “The chapters of awakening the ba which they will recite on the night of burial”. This title suggests the time and place of the ritual performance, and “awakening the ba” is another function ascribed to funerary rituals like the “glorification” texts. As in the Dynastic period, the interment of the body, after the ideal 70-day period of mummification, could be marked with a funerary meal, perhaps in a temporary structure near the tomb. In the Ptolemaic Period (304–30 B.C.), agreements among members of professional associations can stipulate that members will contribute to the burial and funeral feast when a member dies. One such agreement specifies that the association will sponsor “two days of drinking at the pr-nfr (embalming place or funeral tent)”.”

30 Mummies Found in a Fire-Scorched, Greco-Roman-Era, Egyptian Sacrificial Structure

In 2022, archaeologists announced that they had discovered mummies inside a unique family tomb hidden that had been ravaged by fire. Live Science reported: Hidden within a fire-scorched structure near the Nile River in Aswan, Egypt, archaeologists discovered the entrance to a 2,000-year-old family tomb. Inside, they found 30 mummies of various ages, including several arthritis-ridden elderly people, as well as children and a newborn. Though the archaeologists have yet to date the tomb, they suspect a single family buried their dead in it over generations spanning the the Ptolemaic and Roman periods (the first century B.C. to the second or third century A.D.), according to Patrizia Piacentini, a professor of Egyptology and Egyptian Archaeology at the University of Milan, who was co-director of the excavation. [Source: Yasemin Saplakoglu, Live Science published January 26, 2022]

This new tomb is one of more than 300 recently discovered surrounding the Mausoleum of the Aga Khan, a pink granite structure built in the 20th century that sits on top of a slight hill along the Nile River. But while most of the other tombs were found underground or dug into rocky hills, this particular tomb was unique in that it was found inside a larger above-ground structure, which the researchers think was likely used as a place of sacrifice. "It seems that, due to its position along a valley of access to the necropolis, this building was used as a sacred enclosure where sacrifices were offered to the god Khnum in the form of aries, creator god and protector of the fertile floods of the Nile, particularly revered in Aswan," Piacentini told Live Science. "Who better than him could have propitiated the eternal life of those who rested in this necropolis?"

Further supporting its use as a place of sacrifice, Piacentini and the team discovered signs of fire on the structure walls possibly from offering ceremonies; but some of the fire marks may have also been made by grave robbers, she added. Either way, inside that burned structure, they discovered animal bones, plant remains and offering tables. At the bottom of a staircase leading to the tomb entrance — which had been dug out of the rock — , they found a broken offering vase that still contained small fruits. The tomb, which was made up of four deeply-excavated chambers, contained the remains of around 30 mummies.

Some of the mummies were very well preserved, such as the remains of a child tucked inside a terracotta sarcophagus, while others had their bandages and cartonnage, a material ancient Egyptians used to wrap mummies, cut by ancient robbers. The researchers also discovered a knife with an iron blade and wooden handle that may have been used by the plunderers. The researchers also say that Nikostratos was likely once inside the tomb with the other 30 mummies, but was taken out by the robbers. The excavation was a joint venture between the Aswan and Nubian Antiquities Zone in Egypt and by the University of Milan in Italy.

Roman Golden Mummies

At the Valley of the Golden Mummies at Bahariya Oasis in the Western Deserts of Egypt, there are believed to be around 10,000 mummies scattered over a six square kilometer area. Some have been fitted with elaborate masks and have waistcoats covered with gold. The mummy of a five-foot-tall woman was adorned with a crown with four decorative rows of curls and a gilded mask that extended over her chest to disks representing breasts. Decorations had images of cobras and children. [Source: Donovan Webster, National Geographic, October 1999]

Archaeologists discovered the mummy cemetery at Bahariya Oasis (200 miles southwest of Cairo) in 1996. The tombs date between the 4th century B.C. and forth century A.D. and were discovered after the leg of a donkey "fell through the sand" into a tomb. In Roman times, Bahariya was a wealthy a wine producing area.

By 2001, 234 mummies at Bahariya Oasis had been excavated. They mostly dated back to Greco-Roman times — from the 6th century B.C. to the A.D. 2nd century — and included people from a range of social statuses. Many were sheathed in gold. Some had beautifully painted masks. Hundreds of golden coins, jewelry, medallions and beads were found. There was talk of it being one of the richest sources of artifacts in Egypt. Little had been touched by looters.

The most spectacular tombs belonged to the governors who ruled the oasis and their families. Some of them were so rich and powerful they believed they were as powerful as the rulers in Alexandria. They were buried in lavish limestone sarcophagi with hundreds of golden objects and “shawabti” statues. Inside the mummy of a wife of one governor was a heavy solid gold heart, placed were her real heart once was.

The dead were mummified and buried in shafts about 15 feet deep. Some of the mummies were gilded and buried in groups of up to 43 in a single tomb. The mummies and their sarcophagi contained Egyptian-style hieroglyphics and Egyptian gods such as Osiris mixed with people with Greco-Roman hairstyles and clothes and god like Aphrodite. Some contained objects linked to Christianity.

Gilded masks were found with landowners, administrators and military officers. Mummies of children have been found that are completely covered in gold. Other have gilded gypsum masks that extend to their midriffs. Some headless mummies were found.

Mummies with Golden Tongues

In November 2022, archaeologists in Egypt announced they had discovered several ancient mummies with golden tongues in an ancient cemetery near Quesna, a city located about 35 miles (56 kilometers) north of Cairo, according to Egypt's Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. Some of the mummies were buried in wooden coffins with grave goods that included necklaces, pottery, and gold artifacts in the shape of lotus flowers and beetles known as scarabs, the ministry reported. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science published December 1, 2022]

The purpose of gold tongues, it has been hypothesized, was to help transform the deceased into divine beings or help them communicate with the gods. Mummies with gold tongues were popular during the Greco-Roman period (332 B.C.-A.D. 395), Salima Ikram, a professor of Egyptology at The American University in Cairo, told Live Science. The gold tongues are a "hallmark of the later Graeco-Roman period funerary preparations, when golden tongues, and sometimes even 'eyes,' were placed on embalmed bodies," said Ikram. Gold tongues and gold eyes are "manifestations of the transformation of the deceased into divine beings," Ikram said, noting that the ancient Egyptians believed that the flesh of the gods was made of gold. During the Greco-Roman period, ancient Egyptians also believed that gold tongues and gold eyes would "allow the deceased to speak, see, and taste in the afterlife," Ikram said.

mummy's golden tongue

Mummies with gold tongues have been found elsewhere in Egypt, including at Taposiris Magna, an archaeological site on the Mediterranean coast, and Oxyrhynchus (El Bahnasa), an archaeological site in Mimya, Egypt, about 174 kilometers (108 mile) south of Cairo. Taposiris Magna Temple is thought to have been constructed by Ptolemy IV, who ruled Egypt from 221 to 204. B.C. Coins bearing the image of Cleopatra (Cleopatra VII) have also been found at the site. Dr Kathleen Martinez headed a team that found 16 mummies with golden tongues at Taposiris Magna. The two most important ones were found alongside the remains of scrolls and parts of their cartonnage – a kind papyrus or linen-based papier-mache used to construct the intricate “face masks” that envelop the mummified bodies inside their sarcophagi.The first of these bore “gilded decorations of the god Osiris … while the other mummy wears a crown decorated with horns and [a] cobra snake at the forehead.” The chest of the mummy, meanwhile “shows a gilded decoration representing the wide necklace from which hangs the head of a falcon, the symbol of the god Horus.” [Source: Daniel Capurro, The Telegraph, February 3, 2021]

Some golden-tongie mummies predate Greco-Roman times. In December 2021, the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities announced that two golden-tongued mummies — one male, one female — had been discovered at the site of El Bahnasa, known in antiquity, the city of Oxyrhynchus, in Mimya, Egypt. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The 2,500-year-old mummies were found as part of an excavation led by the University of Barcelona. The tomb of the male is particularly important because it was still sealed. Esther Pons Mellado, one of the co-directors of the archaeological mission from the University of Barcelona, told the National, that it is extremely rare to find undisturbed tombs. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, December 22, 2021]

The limestone tomb included a scarab amulet, canopic jars used as part of the mummification process, 400 small earthenware figurines, and the golden tongue, which was still in the mummified man’s mouth. The identity of the male has not yet been determined but archaeologists are hopeful that when the accompanying inscriptions are deciphered, they will have a better sense of who he once was. The quartz tomb of the woman had been disturbed and, as a result, the items inside were in poor condition. Her golden tongue, however, was still lodged in her mouth. A third smaller golden tongued amulet, once the property of a 3-year-old child, was also discovered.

Was the Purpose of the Mummy’s Golden Tongues to Talk With the Gods?

The Egyptian Ministry has stated that golden tongues were meant to enable the deceased to speak to the god Osiris in the afterlife. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: They were, in our modern parlance, a kind of prosthetic or technological device that could enable the wearer to be understood by the gods. In ancient Egyptian theories of the afterlife, in which the righteousness of the deceased was assessed by the gods after death, the ability to converse with one’s judges would have been especially important. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, December 22, 2021]

Though the newly discovered prosthetic tongues are garnering a lot of attention, their existence in Greek and Roman era Oxyrhynchus is well known. An excavation report published by the Egypt Exploration Fund in 1891 notes that some “mummies fell to powder on being touched, and nothing of interest was found in them except another gold tongue-plate.” It would be a mistake to say that gold tongue leaves were common (these are costly items, after all) but they weren’t unheard of.

Tongues aren’t the only body parts that receive some technological enhancement in the mummification process. Artificial eyes made of calcite or linen often replaced the soft tissue in the first millennium B.C.. Though these additions are often assumed to be cosmetic, they may have been a kind of replacement for organic eyes in the afterlife. Eye loss was relatively common in antiquity and a variety of diseases and conditions could cause blindness. In some burials gold eyelid covers were found. Perhaps these inorganic items were supposed to serve as functional substitutes in the afterlife. In his book on Ancient Egypt, Scott Steedman writes that “pieces of gold leaf were placed over tongues, eyes and other body parts… in the belief that these would restore various functions in the afterlife.”

Interestingly, prosthetic tongues do not need to be magically transformed to become functional. The 16th-century barber-surgeon Ambroise Paré, the first doctor to identify “phantom limb” phenomenon, describes an “artificial tongue” that could “supply the defect of speech when the tongue was cut off.” The technology was accidentally discovered, he tells us, by a peasant man who had lost a great deal of his tongue and was drinking from a wooden bowl when he realized that he could make sounds. Beginning with individual letters he relearned how to speak. As Katie Chenoweth writes in her extraordinary book The Prosthetic Tongue, for Paré the artificial tongue was thought to restore the entire faculty of speech and language.

In the case of the golden tongue leaves, the tongues might be more about bodily enhancement than about repairing a broken faculty. Communication between deities (assuming you believe in them) and human beings is difficult. For starters, if deities “speak” in a language, which language is it? For those who made the gold tongues the Egyptian language had gone through multiple periods of transition that were accompanied by two different scripts (hieroglyphics and hieratic, a kind of cursive shorthand). Demotic, a cursive form of Egyptian, had been flourishing in the region for 200 years, which was around the time that Greek arrived in the Nile Delta. On purely a local level, which of these languages would the gods speak? How do gods communicate?

Moreover, given that language is inherently limiting, many people hypothesized that gods spoke using symbols or signs. That might mean using written symbols, but it might also mean any aspect of human experience. Nature, weather patterns, the constellations, the human body, and even coincidences were all ripe for interpretation. And because these symbols or signs weren’t governed by syntax or a narrow range of meaning they had a kind of richness and flexibility appropriate for a powerful deity. Speculation about the ways the gods communicated had consequences: if a deity can speak to us using weather patterns, how do we understand them and how do we speak back?

Faiyum Mummy Portraits

Some of the greatest Roman-era paintings were produced by Romanized Egyptians, who embalmed their dead, wrapped them as mummies, and painted portraits of the deceased on small wooden panels attached at the head of the shroud wrapped around the mummy wrappings. Sometimes these mummies were put on display before they were buried.

These so-called Faiyum portraits, named after the Egyptian oasis town where many were found, were created during Egypt's Roman period (30 B.C. to A.D. 395). They often depict individuals with European heritage, who presumably moved to the area following Alexander the Great's rule in Ptolemaic dynasty (305 to 30 B.C.). and the subsequent Roman period, when the empire made Egypt into a province. The portraits were often painted on wooden panels with the two upper corners cut off so they could be easily inserted into the mummy bandages, over the face of the mummified body, Ben van den Bercken, curator of the Collection Ancient Egypt and Sudan at Allard Pierson, told Live Science. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, published October 17, 2023]

Mummy paintings were rendered from life using colored beeswax on wood panels bounded by linen strips on the outside of the mummy. Pigments mixed with hot wax were used by the Greeks to paint their warships. The Romans used this technique to make portraits on mummy cases in the Faiyum region. It is nor clear whether it is the Egyptian influence or the Roman influence that makes the works so exquisite.

See Separate Article: ROMAN-ERA EGYPTIAN MUMMY PORTRAITS africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian,AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024