Home | Category: New Kingdom (King Tut, Ramses, Hatshepsut)

STUDY OF THE DNA OF KING TUT AND HIS FAMILY

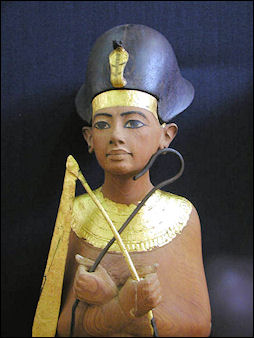

Tutanhkamun Shabti Zahi Hawass wrote in National Geographic, To answer questions about Tutankhamun and his family “we decided to analyze Tutankhamun's DNA, along with that of ten other mummies suspected to be members of his immediate family. In the past I had been against genetic studies of royal mummies. The chance of obtaining workable samples while avoiding contamination from modern DNA seemed too small to justify disturbing these sacred remains. But in 2008 several geneticists convinced me that the field had advanced far enough to give us a good chance of getting useful results. We set up two state-of-the-art DNA-sequencing labs, one in the basement of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and the other at the Faculty of Medicine at Cairo University. The research would be led by Egyptian scientists: Yehia Gad and Somaia Ismail from the National Research Center in Cairo. We also decided to carry out CT scans of all the mummies, under the direction of Ashraf Selim and Sahar Saleem of the Faculty of Medicine at Cairo University. Three international experts served as consultants: Carsten Pusch of the Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen, Germany; Albert Zink of the EURAC-Institute for Mummies and the Iceman in Bolzano, Italy; and Paul Gostner of the Central Hospital Bolzano. [Source: Zahi Hawass, National Geographic, September 2010]

The identities of four of the mummies were known. These included Tutankhamun himself, still in his tomb in the Valley of the Kings, and three mummies on display at the Egyptian Museum: Amenhotep III, and Yuya and Tuyu, the parents of Amenhotep III's great queen, Tiye. Among the unidentified mummies was a male found in a mysterious tomb in the Valley of the Kings known as KV55. Archaeological and textual evidence suggested this mummy was most likely Akhenaten or Smenkhkare.

Our search for Tutankhamun's mother and wife focused on four unidentified females. Two of these, nicknamed the "Elder Lady" and the "Younger Lady," had been discovered in 1898, unwrapped and casually laid on the floor of a side chamber in the tomb of Amenhotep II (KV35), evidently hidden there by priests after the end of the New Kingdom, around 1000 B.C. The other two anonymous females were from a small tomb (KV21) in the Valley of the Kings. The architecture of this tomb suggests a date in the 18th dynasty, and both mummies hold their left fist against their chest in what is generally interpreted as a queenly pose.

Finally, we would attempt to obtain DNA from the fetuses in Tutankhamun's tomb — not a promising prospect given the extremely poor condition of these mummies. But if we succeeded, we might be able to fill in the missing pieces to a royal puzzle extending over five generations.

To obtain workable samples, the geneticists extracted tissue from several different locations in each mummy, always from deep within the bone, where there was no chance the specimen would be contaminated by the DNA of previous archaeologists — or of the Egyptian priests who had performed the mummification. Extreme care was also taken to avoid any contamination by the researchers themselves. After the samples were extracted, the DNA had to be separated from unwanted substances, including the unguents and resins the priests had used to preserve the bodies. Since the embalming material varied with each mummy, so did the steps needed to purify the DNA. In each case the fragile material could be destroyed at every step.

At the center of the study was Tutankhamun himself. If the extraction and isolation succeeded, his DNA would be captured in a clear liquid solution, ready to be analyzed. To our dismay, however, the initial solutions turned out a murky black. Six months of hard work were required to figure out how to remove the contaminant — some still unidentified product of the mummification process — and obtain a sample ready for amplifying and sequencing.

RELATED ARTICLES:

KING TUTANKHAMUN (KING TUT, 1343-1323 B.C.): HIS LIFE, REIGN AND INTRIGUES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

KING TUTANKHAMUN'S FAMILY: HIS WIFE, DAUGHTERS AND DETERMINING THE IDENTITY OF HIS FATHER AND MOTHER africame.factsanddetails.com ;

TUTANKHAMUN’S POOR HEALTH, DEATH AND MUMMIFICATION africame.factsanddetails.com ;

TUTANKHAMUN’S TOMB: LAYOUT, CONTENTS, TREASURES, METEORIC IRON africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DISCOVERY OF THE TOMB OF KING TUTANKHAMUN (KING TUT) africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Discovering Tutankhamun: From Howard Carter to DNA” by Zahi Hawass (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Murder of Tutankhamen: A True Story” by Bob Brier (1998) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun” by T. G. H. James (2000) Amazon.com;

“The Story of Tutankhamun: An Intimate Life of the Boy who Became King” by Garry J. Shaw (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Tutankhamun” by Nicholas Reeves (1990, 2023) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun: A Biography” by Martin Bommas (2024) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass (2005) Amazon.com;

“Amarna Sunset: Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, Ay, Horemheb, and the Egyptian Counter-Reformation” by Aidan Dodson (2009) Amazon.com;

“Pharaohs of the Sun: Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamen” by Rita E. Freed and Yvonne J. Markowitz Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun's Armies” by John Coleman Darnell (2007) Amazon.com; history at time

“Tutankhamun: The Life and Death of a Pharaoh” by David Hamilton Murdoch (1998) Amazon.com;

“King Tutankhamun: The Treasures of the Tomb” by Zahi Hawass (2007) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun, His Tomb and Its Treasures”, lots of images, by I. E. S. Edwards (1976) Amazon.com;

“Egypt's Golden Empire: The Age of the New Kingdom" by Joyce Tyldesley (2011) Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

"The New Kingdom" by Wilbur Smith, Novel (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Temples, Tombs, and Hieroglyphs: A Popular History of Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz (1978, 2009) Amazon.com;

Checking Tutankhamun’s DNA

Getting a sample from a mummy's tooth for DNA testing

Matthew Shaer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Hawass followed up the CT scans with a DNA test of the pharaoh and all the royals that might be related to him. For help, he turned to Yehia Gad, a molecular geneticist at the National Research Centre, in Cairo...In February of 2008, Hawass, Gad, a molecular geneticist named Somaia Ismail and a TV crew from the Discovery Channel, which was funding the study, traveled to Luxor to obtain samples from the mummy. Hawass stipulated that Gad, not any of the visiting scientists, would take the samples. “It’s our country,” Gad recalled to me. “Our ancestry. It made sense that it should be an Egyptian.” [Source: Matthew Shaer, Smithsonian Magazine, December 2014 ~~]

“With the TV team close behind, Hawass’ delegation descended into the burial chamber of tomb KV62. The mummy lay faceup, staring at the murals that swirled across the ceiling. Over the next three hours, using a green-handled biopsy needle, his face hidden by a green mask, Gad painstakingly removed the samples from inside the leg bones. The samples were packed in a sealed container, and Ismail and Gad took it by plane to Cairo. (“I’m absolutely sure I didn’t have one easy breath the entire flight,” Gad told me.) In the capital a multinational team of scientists set about extracting DNA from the samples and comparing it with DNA from ten other purportedly royal mummies. Among them were two unidentified female mummies found in the Valley of the Kings in tomb KV35, and a male mummy, found nearby in tomb KV55, that many believed belonged to Akhenaten, the so-called “heretic king” and the husband of Nefertiti. ~~

“Labs at the Egyptian Museum and Cairo University’s medical school processed the DNA. And two outside scientists—Carsten Pusch, of the University of Tübingen, and Albert Zink, of the EURAC-Institute for Mummies and the Iceman, in Italy—oversaw the study. Hawass’ announcement of the findings in February 2010 coincided with the Discovery Channel’s documentary and a study in the Journal of the American Medical Association, or JAMA. The science was clear, Hawass said: There was almost a hundred percent chance that the male mummy in KV55—the mummy believed to be Akhenaten—was the father of Tutankhamun. The mother, meanwhile, was almost certainly one of the two females in tomb KV35—a woman, the tests showed, who appeared to be Akhenaten’s sister. In other words, Tutankhamun was the product of incest.” ~~

Discovering King Tut’s Father and Mother from the DNA Study

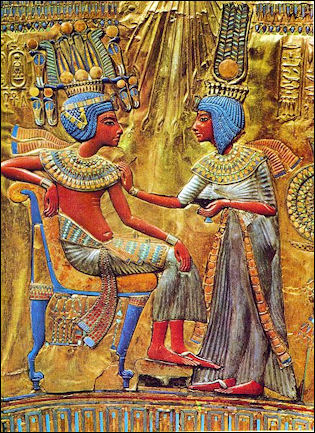

Tutankhamun and his wife Zahi Hawass wrote in National Geographic, “After we had obtained DNA as well from the three other male mummies in the sample — Yuya, Amenhotep III, and the mysterious KV55 — we set out to clarify the identity of Tutankhamun's father. On this critical issue the archaeological record was ambiguous. In several inscriptions from his reign, Tutankhamun refers to Amenhotep III as his father, but this cannot be taken as conclusive, since the term used could also be interpreted to mean "grandfather" or "ancestor." Also, according to the generally accepted chronology, Amenhotep III died about a decade before Tutankhamun was born. [Source: Zahi Hawass, National Geographic, September 2010]

Many scholars believe that his father was instead Akhenaten. Supporting this view is a broken limestone block found near Amarna that bears inscriptions calling both Tutankhaten and Ankhesenpaaten beloved children of the king. Since we know that Ankhesenpaaten was the daughter of Akhenaten, it follows that Tut’ankhaten (later Tutankhamun) was his son. Not all scholars find this evidence convincing, however, and some have argued that Tutankhamun's father was in fact the mysterious Smenkhkare. I always favored Akhenaten myself, but it was only a theory.

Once the mummies' DNA was isolated, it was a fairly simple matter to compare the Y chromosomes of Amenhotep III, KV55, and Tutankhamun and see that they were indeed related. (Related males share the same pattern of DNA in their Y chromosome, since this part of a male's genome is inherited directly from his father.) But to clarify their precise relationship required a more sophisticated kind of genetic fingerprinting. Along the chromosomes in our genomes there are specific known regions where the pattern of DNA letters — the A's, T's, G's, and C's that make up our genetic code — varies greatly between one person and another. These variations amount to different numbers of repeated sequences of the same few letters. Where one person might have a sequence of letters repeated ten times, for instance, another unrelated person might have the same sequence stuttered 15 times, a third person 20, and so on. A match between ten of these highly variable regions is enough for the FBI to conclude that the DNA left at a crime scene and that of a suspect might be one and the same.

Reuniting the members of a family separated 3,300 years ago requires a little less stringency than the standards needed to solve a crime. By comparing just eight of these variable regions, our team was able to establish with a probability of better than 99.99 percent that Amenhotep III was the father of the individual in KV55, who was in turn the father of Tutankhamun.

DNA of King Tut and His Family

We now knew we had the body of Tut's father — but we still did not know for certain who he was. Our chief suspects were Akhenaten and Smenkhkare. The KV55 tomb contained a cache of material thought to have been brought by Tutankhamun to Thebes from Amarna, where Akhenaten (and perhaps Smenkhkare) had been buried. Though the coffin's cartouches — oval rings containing the pharaoh's names — had been chiseled off, the coffin bore epithets associated only with Akhenaten himself. But not all the evidence pointed to Akhenaten. Most forensic analyses had concluded that the body inside was that of a man no older than 25 — too young to be Akhenaten, who seems to have sired two daughters before beginning his 17-year reign. Most scholars thus suspected the mummy was instead the shadowy pharaoh Smenkhkare.

Now a new witness could be called on to help resolve this mystery. The so-called Elder Lady (KV35EL) mummy is lovely even in death, with long reddish hair falling across her shoulders. A strand of this hair had previously been matched morphologically to a lock of hair buried within a nest of miniature coffins in Tut’ankhamun's tomb, inscribed with the name of Queen Tiye, wife of Amenhotep III — and mother of Akhenaten. By comparing the DNA of the Elder Lady with that from the mummies of Tiye's known parents, Yuya and Tuyu, we confirmed that the Elder Lady was indeed Tiye. Now she could testify whether the KV55 mummy was indeed her son.

Much to our delight, the comparison of their DNA proved the relationship. New CT scans of the KV55 mummy also revealed an age-related degeneration in the spine and osteoarthritis in the knees and legs. It appeared that he had died closer to the age of 40 than 25, as originally thought. With the age discrepancy thus resolved, we could conclude that the KV55 mummy, the son of Amenhotep III and Tiye and the father of Tutankhamun, is almost certainly Akhenaten. (Since we know so little about Smenkhkare, he cannot be completely ruled out.)

Our renewed CT scanning of the mummies also put to rest the notion that the family suffered from some congenital disease, such as Marfan syndrome, that might explain the elongated faces and feminized appearance seen in the art from the Amarna period. No such pathologies were found. Akhenaten's androgynous depiction in the art would seem instead to be a stylistic reflection of his identification with the god Aten, who was both male and female and thus the source of all life.

Tutankhamun's most probable genetic lineage

And what of Tutankhamun's mother? To our surprise, the DNA of the so-called Younger Lady (KV35YL), found lying beside Tiye in the alcove of KV35, matched that of the boy king. More amazing still, her DNA proved that, like Akhenaten, she was the daughter of Amenhotep III and Tiye. Akhenaten had conceived a son with his own sister. Their child would be known as Tutankhamun.

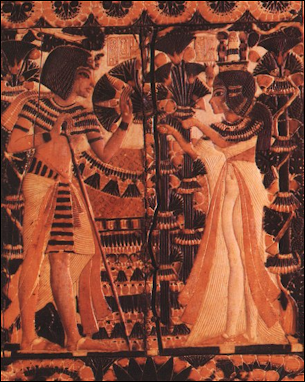

With this discovery, we now know that it is unlikely that either of Akhenaten's known wives, Nefertiti and a second wife named Kiya, was Tutankhamun's mother, since there is no evidence from the historical record that either was his full sister. We know the names of five daughters of Amenhotep III and Tiye, but we will probably never know which of Akhenaten's sisters bore him a child. But to me, knowing her name is less important than the relationship with her brother. Incest was not uncommon among ancient Egyptian royalty. But I believe that in this case, it planted the seed of their son's early death.” The results of the DNA analysis were published in February 2010 in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Critics of Tutankhamun’s DNA Test

There have been many critics of Hawass’s Tutankhamun DNA research. Matthew Shaer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Eline Lorenzen, now a biologist at the University of California, Berkeley, and Eske Willerslev, director of the Centre for GeoGenetics in Denmark, voiced disbelief at the findings. “We question the reliability of the genetic data presented in this study and therefore the validity of the authors’ conclusions,” the two wrote in a letter to JAMA. “Furthermore, we urge a more critical assessment of the ancient DNA data in the context of DNA degradation and contamination.” [Source: Matthew Shaer, Smithsonian Magazine, December 2014 ~~]

“Others also pointed out that Carter and Derry had not exactly been gentle with the mummy; plenty of hands had touched it. So there was ample opportunity for Tut’s DNA (assuming any of it remained intact after 3,000 years) to become contaminated by DNA from other sources. Tom Gilbert, a scientist at the Centre for GeoGenetics, said he has misgivings about the DNA results from Tut. “You must find a way to deal with the contamination issue,” he said, “or else you’ve got nothing.” ~~

“An integral part of the 2010 study was the assertion that the mummy in KV55 was probably Akhenaten—an assertion that allowed Hawass to draw a direct line between one reign and the next. But that, too, has been challenged. The British osteoarchaeologist and forensic anthropologist Corinne Duhig, analyzing published X-rays of the mummy in KV55 and an osteological report by another scholar who had examined the specimen, concluded that the remains cannot belong to Akhenaten; instead, they are possibly those of another royal, the pharaoh Smenkhkare. “Whether the KV55 skeleton is that of Smenkhkare or some previously-unknown prince—and, sadly, recognizing that any proposed lineages leave us with new dilemmas in place of the old—the assumption that the KV55 bones are those of Akhenaten must be rejected before it becomes ‘received wisdom,’” Duhig wrote. In other words, Duhig strongly disputes the incestual ancestry that Hawass and co-workers announced to great fanfare.”

CT Scans of Tutankhamun’s Mummy

“He found the mummy in appalling condition. It had been interred in three coffins, which sat in the sarcophagus like Russian nesting dolls. Over time, resins and ointments used in the mummification process had congealed, sealing the two inner coffins together. Carter had employed increasingly violent maneuvers to remove the mummy from the coffins, and to get at the jewelry and amulets. First, the innermost coffin was left out in the sun to roast, in the hope that the heat would melt down the resins. Next, at Carter’s suggestion, an anatomist named Douglas Derry poured hot paraffin onto the mummy’s wrappings. Later, they pried the body out and yanked various limbs apart, and used a knife to slice the burial mask away from Tut’s head. Carter later reassembled the mummy as best he could (minus the mask and jewelry), and placed it in a wooden tray lined with sand, where it would remain. ~~

“Hawass was looking at a shriveled, broken thing. “It reminded me of an ancient monument lying in ruins in the sand,” he wrote. Still, he and his scientific co-workers walked the mummy, which reclined on the tray, out to the CT scanner. Hawass soon returned to Cairo with roughly 1,700 CT images of Tutankhamun. There, they were examined by Egyptian scientists and three foreign consultants: the radiologist Paul Gostner; Eduard Egarter-Vigl, a forensic pathologist; and Frank Rühli, a paleopathologist based at the University of Zurich.” ~~

King Tutankhamun's Health Determined from CT Scans and DNA Tests

Tutankhamun’s mummy

King Tutankhamun was five feet six inched tall and slightly built and 18 to 20 when he died. In the June 2005 issue of National Geographic, artists and scientists produced striking images of what they believed King Tutankhamun looked like using a CT (computerized tomography) scans and facial reconstruction. The images that were produced showed a fair-skinned young man with a ski-sloped nose, a small cleft planate, an elongated skull, good teeth, and a slight overbite possessed by other members of his family. He had no cavities in his teeth. [Source: A.R. Williams, National Geographic, June 2005]

Tutankhamun age was determined by the maturity of his skeleton (his skull had not closed) and his wisdom teeth (which hadn’t grown in yet). Careful examinations of his head revealed he had a distinctive egg-shaped head, and he lacked the feminine appearance he seems to have in his death mask and other artifacts. He may have fractured his thighbone. CT images, which were part of a study published in the February 2010 of the Journal of the American Medical Association, revealed that Tutankhamun had a club foot and other deformities, meaning he probably had to walk with a cane. DNA analysis of Tutankhamun and his relatives seem to indicate that he had several disorders, some of which ran in his family such as a bone disease and club foot. The authors of the study wrote Tutankhamun was “a young but frail king who needed canes to walk because of the bone-necrotic and sometimes painful Koehler disease II, plus oligodactyly (hypophalangism) in the right foot and clubfoot on the left.”

Zahi Hawass wrote in National Geographic,” When we began the new study, Ashraf Selim and his colleagues discovered something previously unnoticed in the CT images of the mummy: Tutankhamun's left foot was clubbed, one toe was missing a bone, and the bones in part of the foot were destroyed by necrosis — literally, "tissue death." Both the clubbed foot and the bone disease would have impeded his ability to walk. Scholars had already noted that 130 partial or whole walking sticks had been found in Tutankhamun's tomb, some of which show clear signs of use.” [Source: Zahi Hawass, National Geographic, September 2010]

“Some have argued that such staffs were common symbols of power and that the damage to Tutankhamun's foot may have occurred during the mummification process. But our analysis showed that new bone growth had occurred in response to the necrosis, proving the condition was present during his lifetime. And of all the pharaohs, only Tutankhamun is shown seated while performing activities such as shooting an arrow from a bow or using a throw stick. This was not a king who held a staff just as a symbol of power. This was a young man who needed a cane to walk.”

Half of European Men Share King Tut's DNA

In 2011, Reuters reported: “Up to 70 percent of British men and half of all Western European men are related to the Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun, geneticists in Switzerland said. Scientists at Zurich-based DNA genealogy centre, iGENEA, reconstructed the DNA profile of the boy Pharaoh, who ascended the throne at the age of nine, his father Akhenaten and grandfather Amenhotep III, based on a film that was made for the Discovery Channel. [Source: Reuters, Alice Baghdjian, August 1 2011]

The results showed that King Tut belonged to a genetic profile group, known as haplogroup R1b1a2, to which more than 50 percent of all men in Western Europe belong, indicating that they share a common ancestor. Among modern-day Egyptians this haplogroup contingent is below 1 percent, according to iGENEA.

"It was very interesting to discover that he belonged to a genetic group in Europe — there were many possible groups in Egypt that the DNA could have belonged to," said Roman Scholz, director of the iGENEA Centre. Around 70 percent of Spanish and 60 percent of French men also belong to the genetic group of the Pharaoh who ruled Egypt more than 3,000 years ago.

"We think the common ancestor lived in the Caucasus about 9,500 years ago," Scholz told Reuters. It is estimated that the earliest migration of haplogroup R1b1a2 into Europe began with the spread of agriculture in 7,000 BC, according to iGENEA. However, the geneticists were not sure how Tutankhamun's paternal lineage came to Egypt from its region of origin.The centre is now using DNA testing to search for the closest living relatives of "King Tut."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024