Home | Category: New Kingdom (King Tut, Ramses, Hatshepsut)

KING TUTANKHAMUN’S DEATH

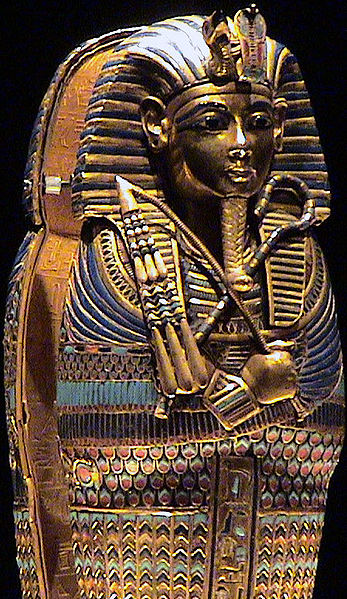

Tutankhamun coffinette King Tutankhamun died in 1324 B.C., nine years into his reign, when he was 19. Some think he died of tuberculosis. Others have argued because he died so young maybe he died in an accident such as falling from a chariot or getting kicked by a horse and died from complications such as septicaemia (a fat embolism) linked with such an accident. Others claim he was poisoned, killed or died fighting or hunting. To support such claims the claimants have pointed to paintings in his tomb that show he received military training and participated in hunts as evidence that such claims were possible. Inside Tutankhamun mummy much of the Pharaoh’s chest is mangled, his breastbone is missing and much of the rib cage has been cut out.

In a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in February 2010, researchers from Egypt, Italy and Germany — using DNA testing, blood type analysis and CT scans — determined that King Tutankhamun mostly likely died of complications from a broken leg exacerbated by malaria. Genetic testing found that the Pharaoh had been infected with the malaria parasite and his immune system was not in good shape. The authors of the study wrote Tutankhamun sustained a “sudden fracture, possibly introduced by a fall” which snowballed into a life-threatening condition when he contacted malaria. Some scholars question the theory based on the reasoning that if he had survived to 19 he probably had some kind of resistance to malaria.

Some scholars believe that Tutankhamun was murdered by Ayem, an advisor to Akhenaten, by a blow to the head. The claim is based on a 1968 X-ray that showed a bone sliver in Tut's skull from some wound and some historical data. This theory was disproved by CT scans in 2005 which showed no evidence of a blow to the head and determined the bone sliver was most likely caused by rough treatment of the mummy in the 1920s by Howard Carter, the the British archaeologist who discovered of King Tutankhamun’s tomb.

RELATED ARTICLES:

KING TUTANKHAMUN (KING TUT, 1343-1323 B.C.): HIS LIFE, REIGN AND INTRIGUES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

KING TUTANKHAMUN'S FAMILY: HIS WIFE, DAUGHTERS AND DETERMINING THE IDENTITY OF HIS FATHER AND MOTHER africame.factsanddetails.com ;

TUTANKHAMUN’S MUMMY: DNA, CT SCANS, DISCOVERIES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

TUTANKHAMUN’S TOMB: LAYOUT, CONTENTS, TREASURES, METEORIC IRON africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DISCOVERY OF THE TOMB OF KING TUTANKHAMUN (KING TUT) africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Discovering Tutankhamun: From Howard Carter to DNA” by Zahi Hawass (2013) Amazon.com;

“The Murder of Tutankhamen: A True Story” by Bob Brier (1998) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun” by T. G. H. James (2000) Amazon.com;

“The Story of Tutankhamun: An Intimate Life of the Boy who Became King” by Garry J. Shaw (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Tutankhamun” by Nicholas Reeves (1990, 2023) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun: A Biography” by Martin Bommas (2024) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass (2005) Amazon.com;

“Amarna Sunset: Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, Ay, Horemheb, and the Egyptian Counter-Reformation” by Aidan Dodson (2009) Amazon.com;

“Pharaohs of the Sun: Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamen” by Rita E. Freed and Yvonne J. Markowitz Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun's Armies” by John Coleman Darnell (2007) Amazon.com; history at time

“Tutankhamun: The Life and Death of a Pharaoh” by David Hamilton Murdoch (1998) Amazon.com;

“King Tutankhamun: The Treasures of the Tomb” by Zahi Hawass (2007) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun, His Tomb and Its Treasures”, lots of images, by I. E. S. Edwards (1976) Amazon.com;

“Egypt's Golden Empire: The Age of the New Kingdom" by Joyce Tyldesley (2011) Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

"The New Kingdom" by Wilbur Smith, Novel (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Temples, Tombs, and Hieroglyphs: A Popular History of Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz (1978, 2009) Amazon.com;

Tutankhamun’s Poor Health Determined from CT Scans of his Mummy

Tutankhamun was frail and slight of build, He stood about five feet five and may have had ailments that impeded his ability to walk normally. In 2005 — for the first time since it was removed from its subterranean burial chamber — Tutankhamun’s mummy was taken out of the plain wooden box Carter placed it in. The mummy was taken outside the tomb to a trailer where the entire mummy was canned with a CT machine, generating 1,700 x-ray images in .62-millimeter-wide cross sections. Three hours later the mummy was returned to its box. There was no evidence of lethal trauma to the skull. The bone slivers that appeared in the 1968 X-ray appear to have been embedded in the packing material stuffed in his skull cavity and may have go there during the embalming process or broken off when Carter handled the body. Tutankhamun skeleton revealed a fracture above the left knee. Some think this may have been the result of mishandling by Carter team.

Zahi Hawass wrote in National Geographic in 2010,” By carrying out CT scans of King Tutankhamun's mummy, we were able in 2005 to show that he did not die from a blow to the head, as many people believed. Our analysis revealed that a hole in the back of his skull had been made during the mummification process.” [Source: Zahi Hawass, National Geographic, September 2010]

Tutankhamun's bone disease was crippling, but on its own would not have been fatal. To look further into possible causes of his death, we tested his mummy for genetic traces of various infectious diseases. I was skeptical that the geneticists would be able to find such evidence — and I was delighted to be proved wrong.

Tutankhamun Injuries

Tutankhamun’s mummified head

Tutankhamun was buried with more than 100 walking sticks and canes. Several paintings show him hunting in his chariot from a seated position. In their 2010 JAMA study, Hawass and co-authors had speculated, based on a reading of the CT scans, that Tut was afflicted by club foot or a similar disability in his left foot, as well as a disorder known as Köhler disease, which can cause pain and swelling and lead to a pronounced limp. [Source: Matthew Shaer, Smithsonian Magazine, December 2014 ~~]

Matthew Shaer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Analyzing the CT scans, Hawass and his colleagues had found a fracture of the lower left femur. “This fracture,” the press release read, “appears different from the many breaks caused by Carter’s team: it has ragged rather than sharp edges, and there are two layers of embalming material present inside.” Perhaps Tutankhamun had been injured in battle or while hunting and the wound had become mortally infected, and he was mummified while the wound was still fresh. And thus the broken femur theory, splashed across newspapers and newscasts worldwide, came to be regarded as something close to fact. ~~

“Yet two scientists who were present for the CT examination told me there was expert disagreement about the fracture at the time, with some arguing that it had led to Tut’s death and others arguing there wasn’t enough data to conclude that. As Jo Marchant notes in her 2013 book The Shadow King: The Bizarre Afterlife of King Tut’s Mummy, “interpreting the clues inside a three-thousand-year-old body isn’t easy, especially one that has been gutted by ancient embalmers, dismembered by modern archaeologists, and thrown about by looters.” ~~

Did Malaria Kill Tutankhamun

The 2010 test results showed that King Tutankhamun suffered from chronic malaria, the result of living near the mosquito-filled Nile marshes. Zahi Hawass wrote in National Geographic: Based on the presence of DNA from several strains of a parasite called Plasmodium falciparum, it was evident that Tutankhamun was infected with malaria — indeed, he had contracted the most severe form of the disease multiple times.

Did malaria kill the king? Perhaps. The disease can trigger a fatal immune response in the body, cause circulatory shock, and lead to hemorrhaging, convulsions, coma, and death. As other scientists have pointed out, however, malaria was probably common in the region at the time, and Tutankhamun may have acquired partial immunity to the disease. On the other hand, it may well have weakened his immune system, leaving him more vulnerable to complications that might have followed the unhealed fracture of his leg we evaluated in 2005.

Researchers in Hawass team found evidence of malaria tropica, a particularly nasty form of the mosquito-borne disease, in DNA samples extracted from the Tut mummy. Hawass speculated that the effects of the malaria, combined with a degenerative bone condition, had killed Tutankhamun.”

Doubts About the Conclusions Made on Tutankhamun’s Health

X-ray of Tutankhamun’s head

In 2013, Egyptologist Salima Ikram and Frank Rühli, a paleopathologist based at the University of Zurich, published an article in a journal of human biology titled “Purported Medical Diagnoses of Pharaoh Tutankhamun.” In regard to the possibility that Tut had suffered from severe epilepsy—a hypothesis put forward by Hutan Ashrafian, a surgeon at Imperial College London, based on his close reading of murals and ancient texts and other sources—Ikram and Rühli said: “There is no hard evidence to support this hypothesis.” [Source: Matthew Shaer, Smithsonian Magazine, December 2014 ~~]

Matthew Shaer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Of the idea that Tut might have been done in by a horse kick to the chest, or by an injury sustained while handling a chariot, or by a furious “rogue hippopotamus” (proposals aired as recently as 2006), the scholars were dismissive: “Although all these dramatic ends to the king’s life are appealing, there remains little proof for these on his body or in the artifacts and texts from that time.” As for the role of malaria, an idea advanced by Hawass and colleagues, Ikram and Rühli said “the claim of malaria being a primary cause of death is disputed by various authors.”~~

“Ikram and Rühli were more willing to entertain the argument that Tut suffered from syndromes affecting his feet. But Ikram wasn’t so sure. “I think part of what was interpreted as club foot could be due to the positioning of the foot during mummification—that could give an impression of distortion,” said Ikram, who, as it happened, was herself walking with a cane, troubled by a pelvis injury, sustained while working in Egypt’s western desert, and a knee ailment. Ikram has conducted experiments in mummifying rabbits, sheep and cats, and in many cases, she said, “bones don’t break, but they certainly curve.” ~~

“In addition to the murals depicting Tut sitting in a chariot, she pointed out, there are paintings in which he was standing. “You can’t pick and choose your evidence,” she said. (In a separate conversation, Yasmin el-Shazly, a scholar at the Egyptian Museum, concurred. “Ancient artwork can be symbolic, or it can be exaggerated in ways that we don’t yet fully understand. It’s dangerous to read it all as realism.”

Rühli initially believed that the leg fracture might have contributed to Tut’s death. But he has grown more skeptical of the idea. “I still think it’s the most likely diagnosis,” he said. “But eight or nine years have passed, and I’ve become much more experienced with the science. I’ve had a lot of time to think about how much pressure we were under.”“The conclusion of Ikram and Rühli’s paper reads: “As time progresses and medical technology improves, tests might be developed that could be carried out on soft tissue that might indicate the presence of diseases that leave no sign on bones—perhaps even a viral disease such as influenza. However, even with the best medical and Egyptological forensic work, it is doubtful that all aspects of Tut’s health and possible causes for his death will ever be known.”“

Tutankhamun’s Mummification

A mural from Tutankhamun’s burial chamber shows the king between Anubis and a goddess identified as either Isis or Nephthys. Ann R. Williams wrote in National Geographic History: The heart believed to be the center of intelligence in ancient Egyptian cosmology, played a crucial part in the afterlife. The god Anubis would weigh the deceased’s heart to determine their fate after death. To protect the organ, it was common for the heart to be separately embalmed and then returned to the body during mummification. But Tut’s mummy has no heart. Perplexed scholars puzzle over why it is absent. One theory is that priests wanted to connect Tutankhamun to the god Osiris, who lost his heart after being murdered and cut to pieces by his brother. Tut’s restoration of the old gods and ending his father’s heresy could have motivated priests to strengthen the association by burying Tut’s heart separately from the mummy. [Source: Ann R. Williams, National Geographic History, November 4, 2022]

Tutankhamun’s Akhenaten tried to introduce monotheism to Egypt and went so far as to destroy images of other gods. Tutankhamun tried to undo his father's changes, turning Egypt's religion back to its traditional focus on multiple gods. A study an article published in 2013 in the journal Études et Travaux, suggests that as part of this program of religious normalization Tutankhamun's mummy was prepared so that it literally appeared as the god Osiris. His penis was mummified at a 90-degree angle (recalling Osiris' fertility); his body and coffins were covered with a black goolike liquid that changed the color of the pharaoh's skin; and his heart was removed, recalling the tale of Osiris being cut apart by his brother Seth. [Source: Owen Jarus last updated October 24, 2022]

David Kamp wrote in Vanity Fair magazine: Tutankhamun’s heart was left intact, but other vital internal organs—his liver, lungs, stomach, and intestines—were removed, preserved, wrapped in cloth, and placed in four mini-coffins, each about a foot and a quarter long and made of gold inlaid with carnelian stone and colored glass. The pharaoh’s body was washed, anointed with herbs and unguents, adorned with more than a hundred amulets, rings, and bangles, and then carefully wrapped in strips of linen. [Source: David Kamp, Vanity Fair, March 19, 2013]

NBC News reported: King Tut appears to have caught fire after his body was mummified and his tomb sealed. Experts who have studied the mummy believe that King Tut's linen wrappings, which were soaked in flammable embalming oils, may have reacted with oxygen in the air to start a chain reaction that ignited the king's corpse, "cooking" it at about 390 degrees Fahrenheit (200 degrees Celsius). A rushed burial was likely behind the botched embalming job that caused the fire. But the hasty burial of this royal figure also gives rise to another mystery: It's possible that King Tut's tomb was originally built for someone else, and there may be other, undiscovered mummies buried in the same tomb. [Source Marc Lallanilla, NBC News, November 5, 2013]

Tutankhamun’s Entombment and Funeral

Tutankhamun tomb “ David Kamp wrote in Vanity Fair magazine: The mummy was laid in a coffin of solid gold, the delicate face on its lid fashioned in Tutankhamun’s image and framed by the customary pharaonic nemes, or striped headdress. Before the lid went on, the pharaoh’s undertakers gently placed over his head a magnificent 22-pound portrait mask in burnished gold: the nose pointed, the cheeks smooth, and the lips and chin fleshy, with wide eyes outlined in lapis lazuli.

[Source: David Kamp, Vanity Fair, March 19, 2013]

“The gold coffin was placed inside a larger coffin of gilded wood, which was housed, nesting-doll-style, inside a still-larger coffin, also of gilded wood. The nested coffins were then lowered into a heavy, rectangular sarcophagus of yellow quartzite, its sides etched with hieroglyphs, its corners featuring relief carvings of the protective goddesses Isis, Nephthys, Selket, and Neith. For good measure, the sarcophagus was itself nested in four ornately decorated chests known as shrines, each bigger than the last. The outermost shrine, made of gilded cedar, was 16 1/2 feet long and 9 feet high. Tutankhamun’s preserved viscera got their own gilded shrine, its four sides guarded by the same four goddesses—this time spectacularly rendered as fully three-dimensional sculptures of gold-painted wood, each about three feet high, with arms outstretched and heads turned sideways, as if on the lookout for intruders.

“The pharaoh’s remains were carried down into a tomb west of the Upper Nile, in the vast royal necropolis known as the Valley of the Kings. So, too, were all manner of mementos and goods from Tutankhamun’s life: disassembled chariots, a childhood gaming board, furniture, lamps, sculpture, weapons, jewelry. The tomb, a mini-labyrinth of tunnels, chambers, and blocked passageways, was sealed. And that was that. Tutankhamun’s followers had done what they could to equip the pharaoh for a safe journey through the underworld to a joyful afterlife.”

Did King Tutankhamun Have A Funeral Meal?

Dorothea Arnold of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “In 1941, Herbert Winlock proposed that the floral collars and most of the above-described pottery vessels were used at a meal. In reconstructing this event, Winlock was much influenced by the ubiquitous depictions of banquets in Dynasty 18 Theban tombs. But the German Egyptologist Siegfried Schott demonstrated that these images in fact illustrate not a funeral feast but a festival that was celebrated annually in ancient Thebes (present-day Luxor). During this feast—called "The Beautiful Feast of the Valley"—an image of the god Amun was conveyed from his temple at Karnak on the east bank of the Nile to the cemeteries and temple area on the west bank. While the image rested overnight in the sanctuary, people feasted in and in front of the tombs of their ancestors. This "Feast of Drunkenness" was not a celebration at a funeral but a religious festival that included the dead of the community. The objects and vessels in KV 54 cannot have anything to do with this occasion, since they were buried together with mummification leftovers. [Source: Dorothea Arnold, Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2010, metmuseum.org \^/]

“New Kingdom Theban reliefs and paintings reveal, however, that another meal, this one of a more sedate character, took place at a funeral in connection with rites performed for the deceased's statue, another important item in Egyptian funerals that provided a place of materialization for a dead person's soul. These statue rites are repeatedly depicted to have been enacted in a garden setting, with food offerings set out on tables and drinks in large jars like some found in KV 54 resting under canopies. \^/

“Interestingly—and importantly for an interpretation of the objects from KV 54—some representations of statue rites also show that after the conclusion of these rites, all vessels used for offerings were smashed. Almost all pots in the KV 54 find were found broken into pieces. It can, therefore, be suggested that the above-described vessels and other remains of food (such as animal bones) from KV 54 were part of a display of food offerings set out at the consecration of a statue of King Tutankhamun. As was customary in antiquity, the participants in the offering ritual would have consumed the food after the ceremonies were concluded. Communal meals in the presence of a deceased's effigy are, moreover, known to have taken place in many cultures and are certainly attested to have taken place in Roman Egypt. \^/

“Winlock assumed that the floral collars were worn by the participants of a funeral meal. It is, however, more probable that a number of floral collars were created to adorn the various coffins—and maybe images—of the king. One large example made of a very similar choice of plants as the one found on the three Museum collars was eventually placed on Tutankhamun's innermost coffin and found there by Howard Carter; the others would then have been stored away among the leftovers of the embalming process.” \^/

Tutankhamun's Mortuary Temple, the Site of His Mummification and Statue Rites?

Dorothea Arnold of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The mummification and statue rites for a king were held, not in front of the king's tomb in the Valley of the Kings, but more likely at the site of the king's mortuary temple. Mortuary temples were built by the pharaohs of the New Kingdom for the daily celebration of their cult after death as well as the worship of Amun, the supreme god of Thebes, and other deities; and all of these temples were situated close to the agricultural land east of the Valley of the Kings. [Source: Dorothea Arnold, Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2010, metmuseum.org \^/]

King Tut's throne

“We do not know where Tutankhamun’s mortuary temple stood and whether it was ever fully completed. A relief in the Museum (05.4.2) depicting a man called Userhat, who is said to have served at Tutankhamun's mortuary temple, is the only evidence extant that a cult ever took place there. A site for the temple, however, must certainly have been chosen and prepared by the time of the king's funeral, and it is there that both his mummification and statue rites most probably took place.\^/

“This explains not only why the leftovers of the king's mummification were packed up together with the remains of offerings dedicated to his statue, but is also congruent with the garden settings in which the statue rites are depicted. In the end, the whole lot (mummification leftovers and food offering remains) were then conveyed in their large containers from the mortuary temple site to the Valley of the Kings together with all the other articles that would fill the king's tomb.” \^/

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024