Home | Category: New Kingdom (King Tut, Ramses, Hatshepsut)

KING TUTANKHAMUN' S FAMILY

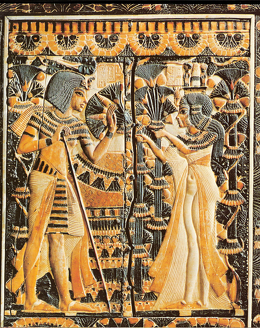

Tutankhamun and his wife

King Tutankhamun (ruled 1334 to 1325 B.C.), better known as King Tut, became a pharaoh at age 9 and died when he was 19. Tutankhamum is believed to be the son of the great pharaoh Akhenaten. Nefertiti, Akhenaten’s first wife, was his stepmother. Tutankhamun’s reign lasted for 16 years. Sometime during his reign he married Ankhesenpaaten. Apart from the return to Thebes and the cult of Amun, few events of his reign were documented. King Tutankhamun was the last heir of a powerful family that ruled ancient Egypt for many centuries. Although his rule was unfilled his death was treated with great fanfare as he was the last of his line. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

For a long time scholars were not even sure who Tutankhamun’s parents were. They believed his father or grandfather was Akhenaten (also known as Amenhotep IV) and his mother was Akhenaten’s beloved secondary wife Kiya. It was also plausible for Tutankhamun to be Akhenaten’s half brother. In February 2010, researchers from Egypt, Italy and Germany — using DNA analysis — determined Tutankhamun’s father was Akhenaten and his mother was Akhenaten’s sister. The DNA analysis also determined that Tutankhamun’s father Akhenaten was the son of Amenhotep III and identified Queen Tiye as the mother of both Akhenaten and his sister-wife.

RELATED ARTICLES:

KING TUTANKHAMUN (KING TUT, 1343-1323 B.C.): HIS LIFE, REIGN AND INTRIGUES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

TUTANKHAMUN’S POOR HEALTH, DEATH AND MUMMIFICATION africame.factsanddetails.com ;

TUTANKHAMUN’S MUMMY: DNA, CT SCANS, DISCOVERIES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

TUTANKHAMUN’S TOMB: LAYOUT, CONTENTS, TREASURES, METEORIC IRON africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DISCOVERY OF THE TOMB OF KING TUTANKHAMUN (KING TUT) africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Story of Tutankhamun: An Intimate Life of the Boy who Became King” by Garry J. Shaw (2022) Amazon.com;

“Amarna Sunset: Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, Ay, Horemheb, and the Egyptian Counter-Reformation” by Aidan Dodson (2009) Amazon.com;

“Pharaohs of the Sun: Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamen” by Rita E. Freed and Yvonne J. Markowitz Amazon.com;

“The Lost Queen: Ankhsenamun, Widow of King Tutankhamun” by Cheryl L. Fluty (2009) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun” by T. G. H. James (2000) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Tutankhamun” by Nicholas Reeves (1990, 2023) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun: A Biography” by Martin Bommas (2024) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass (2005) Amazon.com;

“Discovering Tutankhamun: From Howard Carter to DNA” by Zahi Hawass (2013) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun's Armies” by John Coleman Darnell (2007) Amazon.com; history at time

“The Murder of Tutankhamen: A True Story” by Bob Brier (1998) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun: The Life and Death of a Pharaoh” by David Hamilton Murdoch (1998) Amazon.com;

“King Tutankhamun: The Treasures of the Tomb” by Zahi Hawass (2007) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun, His Tomb and Its Treasures”, lots of images, by I. E. S. Edwards (1976) Amazon.com;

“Egypt's Golden Empire: The Age of the New Kingdom" by Joyce Tyldesley (2011) Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

"The New Kingdom" by Wilbur Smith, Novel (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Temples, Tombs, and Hieroglyphs: A Popular History of Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz (1978, 2009) Amazon.com;

Archaeological Record on Tutankhamun's Parentage

The archaeological record on Tutankhamun's parentage is ambiguous. Zahi Hawass wrote in National Geographic:In several inscriptions from his reign, Tutankhamun refers to Amenhotep III as his father, but this cannot be taken as conclusive, since the term used could also be interpreted to mean "grandfather" or "ancestor." Also, according to the generally accepted chronology, Amenhotep III died about a decade before Tutankhamun was born. [Source: Zahi Hawass, National Geographic, September 2010]

Many scholars believe that his father was instead Akhenaten. Supporting this view is a broken limestone block found near Amarna that bears inscriptions calling both Tutankhaten and Ankhesenpaaten beloved children of the king. Since we know that Ankhesenpaaten was the daughter of Akhenaten, it follows that Tut’ankhaten (later Tutankhamun) was his son. Not all scholars find this evidence convincing, however, and some have argued that Tutankhamun's father was in fact the mysterious Smenkhkare. I always favored Akhenaten myself, but it was only a theory.

Dr. Marc Gabolde, wrote in for the BBC: “ Until recently, it was thought that the six daughters of Akhenaten and Nefertiti were the couple's only offspring. However, in one chamber of the Royal Tomb, just outside the room devoted to the funeral vigil for Akhenaten's second daughter, Meketaten, a small child is depicted in the arms of a wet-nurse. It has long been believed that Meketaten died in childbirth and that this infant was hers. However, she was only about nine years old at the time of her death and her sarcophagus proves that she was scarcely taller than one metre. [Source: Dr. Marc Gabolde, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“What remains of the inscription referring to the child reads: '(1) [...] born of (2) [...] Neferneferua[ten] Nefertiti, who lives now and forever more' [(1) and (2) indicate two columns; [...] indicates missing text.] Given the length of the missing parts of the inscription and the similarity in composition to the titles given to other royal offspring at Amarna it is clear that we are dealing with a child of Nefertiti. And given that by the time of the birth of this child, we know that the six daughters of Akhenaten and Nefertiti were already born and that, moreover, three of them were dead, the baby is necessarily different from any of the known princesses. So we must be dealing with a seventh child of Nefertiti. |::|

“The most likely candidate is Tutankhamun, known during this period as Tutankhaten. Indeed, a block, now split in two, from the nearby site of Hermopolis still bears the insignia of the prince Tutankhaten accompanied by that of a princess whose name, unfortunately, is missing. Another block at Hermopolis confirms that Tutankhaten had at least one sister and probably two. On this block, a prince, identifiable by his loincloth, can be seen sitting on an adult's lap, together with traces of the figures of two other children. It was a rule in the official monuments of Amarna, that Nefertiti's children should never be shown alongside those of any other wife of Akhenaten. As Nefertiti is the only one of his wives known to have had more than one child, it is probable that Akhenaten and Nefertiti were the parents of Tutankhamun. |::|

Tutankhamun's Father

Akhenaten

Ann R. Williams wrote in National Geographic History: Clues uncovered in Tut’s tomb — KV62, the 62nd burial complex found in the valley — confirm that he was one of the successors of heretic king Amenhotep IV. The latter chose a new name, Akhenaten, meaning “effective for the Aten,” the god that the king decided to worship to the exclusion of all others. In the distinctive art of the era, the Aten appears as a sun disk whose rays deliver blessings and eternal life. [Source: Ann R. Williams, National Geographic History, November 4, 2022]

Tut’s original name was Tutankhaten, “living image of the Aten.” He was surely born in Akhenaten’s new capital, Akhetaten — “horizon of the Aten” — today the archaeological site of Amarna. Everyone at court, government officials and bureaucrats, and thousands of artisans and laborers had moved to Akhetaten with the king, abandoning the traditional capital of Thebes, modern Luxor. That occurred in the midst of a religious revolution in which Akhenaten made the Aten the country’s one official god. As centuries of polytheistic tradition were suddenly upended, with the old gods falling out of favor, confusion and terror must have gripped the country.

According to the results of DNA tests published in 2010, a decayed mummy found in tomb KV55 was Tut’s father. Some Egyptologists believe that it was Akhenaten, based largely on royal epithets on the coffin, but other experts have their doubts. They wonder if the bones might belong to someone else — perhaps a shadowy figure named Smenkhkare, who may have been Akhenaten’s brother.

Tutankhamun's Mother

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Perhaps one of the most surprising mysteries still surrounding the family of King Tutankhamun is the identity of his mother. She is never mentioned in an inscription and, even though the pharaoh’s tomb is filled with thousands upon thousands of personal objects, not a single artifact states her name. Two female mummies found in 1898 in a side chamber of the Valley of the Kings’ tomb of Amenhotep II, referred to as the “Elder Lady” and the “Younger Lady,” provide some tentative answers. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2022]

At some point, these two mummies, along with those of nine kings, including Tut’s grandfather Amenhotep III, had been moved to the tomb. By comparing DNA taken from the Elder Lady’s mummy with that from a lock of brown hair found in a miniature coffin inscribed with the name Tiye — Tut’s grandmother, the wife of Amenhotep III — inside Tut’s tomb, Egyptologist Zahi Hawass was able to identify the Elder Lady as Tiye. Tutankhamun, whose mother died when he was very young, is thought to have been particularly close to Tiye, so perhaps the lock of hair served as a memento.

The Younger Lady’s mummy is badly damaged. According to Hawass, she was 5 feet 1 inch tall, and lived to between 25 and 35. CT scans of the mummy performed by radiologists Sahar Saleem and Ashraf Selim of Cairo University suggest she had a serious injury on the left side of her face that was most likely inflicted before mummification. As Hawass explains, the subcutaneous embalming packs and filling were not disturbed, and the fractured fragments of her left jawbone were missing. “This may denote that the broken bone fragments were removed by the embalmers, who also partly cleaned the region of the injury,” says Hawass.

Although the Younger Lady is not named, she is thought to be Tut’s mother, a daughter of Amenhotep III and Tiye, and wife to her brother Akhenaten, Tut’s father. “We know that it is unlikely that either of Akhenaten’s known wives, Nefertiti or Kiya, was Tutankhamun’s mother, as there is no evidence from the sources that either was Akhenaten’s sister,” says Hawass. (Tut’s mother is known to have been one of Akhenaten’s sisters.) “Just which of his many sisters the Younger Lady is may never be known — he seems to have had almost forty sisters.”

Discovering King Tut’s Father and Mother from the DNA Study

Zahi Hawass wrote in National Geographic, “After we had obtained DNA from the three other male mummies in the sample — Yuya, Amenhotep III, and the mysterious KV55 — we set out to clarify the identity of Tutankhamun's father. Once the mummies' DNA was isolated, it was a fairly simple matter to compare the Y chromosomes of Amenhotep III, KV55, and Tutankhamun and see that they were indeed related. (Related males share the same pattern of DNA in their Y chromosome, since this part of a male's genome is inherited directly from his father.) But to clarify their precise relationship required a more sophisticated kind of genetic fingerprinting. [Source: Zahi Hawass, National Geographic, September 2010]

Along the chromosomes in our genomes there are specific known regions where the pattern of DNA letters — the A's, T's, G's, and C's that make up our genetic code — varies greatly between one person and another. These variations amount to different numbers of repeated sequences of the same few letters. Where one person might have a sequence of letters repeated ten times, for instance, another unrelated person might have the same sequence stuttered 15 times, a third person 20, and so on. A match between ten of these highly variable regions is enough for the FBI to conclude that the DNA left at a crime scene and that of a suspect might be one and the same.

Reuniting the members of a family separated 3,300 years ago requires a little less stringency than the standards needed to solve a crime. By comparing just eight of these variable regions, our team was able to establish with a probability of better than 99.99 percent that Amenhotep III was the father of the individual in KV55, who was in turn the father of Tutankhamun.

See Separate Article: TUTANKHAMUN’S MUMMY: DNA, CT SCANS, DISCOVERIES africame.factsanddetails.com

King Tutankhamun and Royal Incest

The various maladies discovered on Tutankhamun's mummy are thought to have been the result of inbreeding between his father and mother — his father’s sister. Zahi Hawass wrote in National Geographic, “In my view...Tutankhamun's health was compromised from the moment he was conceived. His mother and father were full brother and sister. Pharaonic Egypt was not the only society in history to institutionalize royal incest, which can have political advantages. (See "The Risks and Rewards of Royal Incest.") But there can be a dangerous consequence. Married siblings are more likely to pass on twin copies of harmful genes, leaving their children vulnerable to a variety of genetic defects. Tut’ankhamun's malformed foot may have been one such flaw. We suspect he also had a partially cleft palate, another congenital defect. Perhaps he struggled against others until a severe bout of malaria or a leg broken in an accident added one strain too many to a body that could no longer carry the load. [Source: Zahi Hawass, National Geographic, September 2010]

There may be one other poignant testimony to the legacy of royal incest buried with Tutankhamun in his tomb. While the data are still incomplete, our study suggests that one of the mummified fetuses found there is the daughter of Tutankhamun himself, and the other fetus is probably his child as well. So far we have been able to obtain only partial data for the two female mummies from KV21. One of them, KV21A, may well be the infants' mother and thus, Tutankhamun's wife, Ankhesenamun. We know from history that she was the daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, and thus likely her husband's half sister. Another consequence of inbreeding can be children whose genetic defects do not allow them to be brought to term.

So perhaps this is where the play ends, at least for now: with a young king and his queen trying, but failing, to conceive a living heir for the throne of Egypt. Among the many splendid artifacts buried with Tutankhamun is a small ivory-paneled box, carved with a scene of the royal couple. Tutankhamun is leaning on his cane while his wife holds out to him a bunch of flowers. In this and other depictions, they appear serenely in love. The failure of that love to bear fruit ended not just a family but also a dynasty.

Tutankhamun's most probable genetic lineage

Did King Tut's Sisters Take the Throne Before He Did?

Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science: Archaeologists have known that a "mystery female pharaoh" ruled ancient Egypt before the renowned King Tutankhamun ascended the throne. Though they knew the royal name of this female king — Neferneferuaten Ankhkheperure — her true identity has remained elusive; however, Tut's famed tomb was originally meant for her. Now, a researcher says the mystery woman might be none other than King Tut's two older sisters, according to the investigator's new, and controversial, research. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, October 24, 2022]

It's possible that after King Tut's dad, King Akhenaten, died, his youngest surviving daughter, Neferneferuaten, began ruling Egypt at age 12, likely at first disguised as a male. During this time, Neferneferuaten's older sister Meritaten served as her great royal spouse.But Meritaten didn't keep that "great royal spouse" title for long. "It looks like after one year, Meritaten had herself crowned as pharaoh, as well," said researcher Valérie Angenot, professor of art history and specialist in visual semiotics at the University of Quebec in Montreal. "They actually ruled as two queen pharaohs, instead of this more traditional view of one pharaoh and one queen." [In Photos: The Life and Death of King Tut]

However, Angenot's idea about the "two queen pharaohs" is controversial among Egyptologists, many of whom think that the mystery queen is none other than Nefertiti, the principal wife of King Akhenaten and stepmother to King Tut.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see King Tut's Sisters Took the Throne Before He Did, Controversial Claim Says, Live Science livescience.com

Ankhesenamun, Tutankhamun’s Wife

Tutankhamun married Ankhesenamun, who may have also been his half sister as she was Akhenaten and Nefertiti’s daughter. Ann R. Williams wrote in National Geographic History: By the time Tut and his wife were married they had changed their names to reflect the country’s religious reset after Akhenaten's effort to introduce monotheism and the rehabilitation of Amun, a powerful god based in Thebes. They were Tutankhamun, “living image of Amun,” and Ankhesenamun, “she lives through Amun.” [Source: Ann R. Williams, National Geographic History, November 4, 2022]

Ankhesenamun was around the same age as Tutankhamun, or older and had been married to her own father. A scene on gilded wooden shrine from his tomb show her handing Tutankhamun an arrow to shoot some ducks hiding among papyrus reeds. The couple produced two children, both girls but they died in the womb.

Princess Ankhesenamun (also known as Anknespaaten, Enkhosepaaton or Ankhesenaton Ankhesenamon) was the third daughter of Pharaoh Akenaton and Queen Nefertiti. According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: Following the deaths of her two older sisters, Meritaton and Meketaton and Akenaton, Ankhesenamun was forced to marry her half-brother Tutankhaton (Nefertiti's son) in order to sustain the control of the throne. Ankhesenamun carried two children to term, but they were both stillborn.” After Tutankhamon’s early death Ankhesenamon became while still in her twenties. Tutankhamon died before an heir to the throne was born or even conceived. Because of the unpopularity of her father's idealism, Ankhesenamon didn't have the public or political support to hold the throne herself. The throne of Egypt was threatened and she was on her own. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Ann R. Williams wrote in National Geographic History: Although incest may have been an attractive strategy for keeping power in the family, it was genetically risky. In this instance the risk did not pay off. Two fragile, mummified fetuses were discovered in King Tut’s tomb, each with her own tiny nested inner and outer wooden coffins. They were his daughters with Ankhesenamun. The young couple tried to do their duty and produce an heir, but couldn’t. The shared genes they inherited probably made it impossible for them to conceive a healthy baby, thus setting up the inevitable end of the 18th dynasty. [Source: Ann R. Williams, National Geographic History, November 4, 2022]

Tutankhamun’s Daughters

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: For three years after his 1922 discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb, archaeologist Howard Carter did not think much about an undecorated wooden box that turned out to contain two small resin-covered coffins, each of which held a smaller gold-foil-covered coffin. Inside these coffins were two tiny mummies. Preoccupied, Carter numbered the box 317 and did little to study it or its contents, only unwrapping the smaller of the two mummies, which he called 317a. The larger mummy he called 317b. The mummies were not carefully examined until 1932, when they were autopsied and photographed, at which time they were identified as stillborn female fetuses. But the most recent work on these two tiny girls, undertaken by radiologist Sahar Saleem of Cairo University, tells more of their story. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2022]

A decade ago, as head radiologist of the Egyptian Mummy Project, Saleem CT scanned the two fetuses, the first time any mummified fetus was studied using this technology. Though there is no evidence of the babies’ personal names — they are identified only by gold bands on the coffins calling them Osiris, the Egyptian god of the dead — they were, in fact, the daughters of Tutankhamun and his wife, Ankhesenamun, and were buried alongside their father after his death. Although both mummies were badly damaged, Saleem found that the girls died at 24 and 36 weeks’ gestation. It was previously known that the older girl, 317b, had had her organs removed as was typical to prepare the deceased for mummification. Saleem found an incision used to remove the organs on the side of 317a, as well as packing material of the sort placed under the skin of royal mummies to make them appear more lifelike. This contradicted the long-held belief that, unlike her sister, the younger girl had not been deliberately mummified.

Similarly, by scanning the mummies, Saleem was able to definitively disprove previous claims that the girls had suffered from congenital abnormalities such as spina bifida. “They got it wrong,” she says. “The damage to their skeletons is a result of postmortem fractures and poor storage. For example, 317b’s elongated head is not a result of cranial abnormalities as has previously been said, but because she has a broken skull.” For Saleem, though, what she has learned about Tutankhamun’s daughters goes beyond these scientific questions. “I try to feel the person as a human in their journey of life,” she says. “Regardless of their age at death, Tut’s daughters were seen as worthy of receiving the most expert mummifications, of a royal burial with their father, and of an afterlife.”

Ankhesenamun After Tutankhamun’s Death

Because of the unpopularity of her father Akhenaten and his iconoclastic monotheism, Ankhesenamon — Tutankhamun’s wife — didn't have the public or political support to hold on to power after Tutankhamun’s death. the throne herself. The throne of Egypt was threatened and she was on her own. According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“She feared that once the public was informed of the death of the young pharaoh the country might fall apart. Also, she was worried about the growing political powers that wanted to take control of the throne. The two leaders of these political powers were Aye, the grand vizier and Ankhesenamon's grandfather, and Horemhab (or Harmhab), the general of the army. Ankhesenamon wrote to Suppliliumas, the Hittite King, in northern Egypt for help. “My husband is dead, and I have no son,” she wrote.

She asked the Hittite king to send one of his sons to be her husband. If she was successful in her plan, she would have a husband with enough power to keep the enemies away, but she would still also have some control over the throne. However, Suppliliumas was suspicious and delayed sending one of his sons. This insulted the young queen and she wrote back to Suppliliumas in urgency. +\

The Hittite king sent one of his sons, Zannanza, but he was murdered before he could reach her. Time ran out for Ankhesenamon and her last and only hope to sustain her power was dashed. She was forced to marry her grandfather Aye, who was over forty years older than her. With her fate sealed, she was finally able to give proper respect to her late husband, Tutankhamon. At his funeral, the conquered queen placed a wreath of flowers on his head.

Ankhesenamun married Ay eight months after the death of Tutankhamun. Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “Traditionally a king was buried seventy days after his death, but it is possible that Tutankhamun lay unburied for eight months while the political plotting and maneuverings were being played out. Ankhesenamun rapidly disappears from the records after her marriage to Ay and her name was hacked out of some monuments and we can only imagine her fate after her attempt to bring a foreigner to rule Egypt. DNA testing suggests that she may be one of the two female mummies found in KV21. Ay was king for only four years then succeeded by Horemheb and although the records state the eighteenth dynasty ended with Horemheb, Tutankhamun was in fact the last member of his family to rule” Egypt. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

Did Tutankhamun Connect with His Ancestors by Using Their Cream Vessels

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine: By studying some of the more unassuming items in Tutankhamun tomb’s inventory — a set of 11 alabaster vessels — Egyptologist Martin Bommas of Macquarie University has found evidence that Tutankhamun himself also took a keen interest in his country’s past. Bommas says these vessels were originally used by some of Tutankhamun’s illustrious predecessors, whose names are inscribed on them: the pharaoh Thutmose III, who reigned more than a century before Tutankhamun, as well as the boy king’s grandparents Amenhotep III and Tiye. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2022]

The vessels held emulsions, creams, and oils, residues of which were still present when Carter opened the tomb in 1922. “These were not artifacts that you put on your mantelpiece, they were in daily use,” says Bommas. “The interesting thing is they were restored over a period of time, perhaps even in Tutankhamun’s lifetime.” Given that such vessels could have been made quite cheaply, the question is why Tutankhamun didn’t request new pots inscribed with his own name. Bommas believes the young pharaoh opted to use these antiquated objects as a way of surrounding himself with the aura of history. “At some point, as part of his education, Tutankhamun would have asked, ‘Who were my forefathers? Who was my granddad?’” says Bommas. “And they would have looked through the palaces and collected the vessels and said something like, ‘This is the pot that Thutmose III used after his Euphrates campaign.’ This would have been a wonderful way for Tutankhamun to link with his past.”

In particular, Bommas suggests, the vessels may have been a way for Tutankhamun to reconnect with traditions that held sway before his father, the pharaoh Akhenaten, shifted Egypt’s religious focus from the creator god Amun-Ra to the god of light, Aten. As Tutankhamun made clear in the so-called Restoration Stela, found in the Karnak Temple, Akhenaten’s religious experiment had been a disaster for the country. “The temple and cities of the gods and goddesses…were fallen into decay and their shrines were fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass,” he writes. According to Bommas, “The problem for Tutankhamun was to reconnect with the time before Atenism. There was no other way for him but to study history, and these vessels informed him about the importance of the Egyptian past

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024