Home | Category: New Kingdom (King Tut, Ramses, Hatshepsut)

KING TUTANKHAMUN

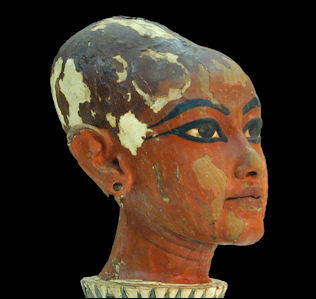

Tut mask King Tutankhamun lived between roughly 1343 B.C. and 1323 B.C. and ruled 1334 to 1323 B.C. Better known as King Tut and lived between roughly 1343 B.C. and 1323 B.C. and often called the "boy-king," he became a pharaoh at age 9 or 10 and died when he was 19. Little is known of his life. Nothing in particular distinguished his career except a few foreign military campaigns, and he probably would not be remembered were it not for the discovery of his unlooted tomb in 1922, which caused a big brouhaha even though relative to other Pharaohs it was not even a particularly grand tomb. Tutankhamun’s name was not even included on the classic “King’s List” at the temples of Abydos and Karnak. Despite all this King Tut is the Pharaoh the public knows best. [Source: Richard Covington, Smithsonian magazine, June 2005]

Tutankhamum is believed to be the son of Akhenaten. Nefertiti, Akhenaten’s first wife, was his stepmother. Tutankhamun’s his reign lasted for 16 years. Sometime during his reign he married Ankhesenpaaten. Apart from the return to Thebes and the cult of Amun, few events of his reign were documented. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

King Tutankhamun was the last heir of a powerful family that ruled ancient Egypt for many centuries. Although his rule was unfilled his death was treated with great fanfare as he was the last of his line. It is astonishing how Tutankhamun continues do fascinate people today. More than 8 million people showed up to see his mask and artifacts from his tomb during the King Tut tour of the United States in the 1977. The comedian Steve Martin gave his career a big boost when he recorded a silly song about the pharaoh around the time of the tour. An exhibit in the mid 2000s called “Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs” — similar to one in 1977 — cleared $10 million in each city it appeared in. The admission fee was as high as $30. More than a million people saw the exhibit in Chicago and Philadelphia and nearly a million saw it in Los Angeles. The tour took place in spite of a ban that had been imposed after a gilt statue from Tut’s tomb was broken during a tour of Germany in 1982.

RELATED ARTICLES:

KING TUTANKHAMUN'S FAMILY: HIS WIFE, DAUGHTERS AND DETERMINING THE IDENTITY OF HIS FATHER AND MOTHER africame.factsanddetails.com ;

TUTANKHAMUN’S POOR HEALTH, DEATH AND MUMMIFICATION africame.factsanddetails.com ;

TUTANKHAMUN’S MUMMY: DNA, CT SCANS, DISCOVERIES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

TUTANKHAMUN’S TOMB: LAYOUT, CONTENTS, TREASURES, METEORIC IRON africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DISCOVERY OF THE TOMB OF KING TUTANKHAMUN (KING TUT) africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Tutankhamun” by T. G. H. James (2000) Amazon.com;

“The Story of Tutankhamun: An Intimate Life of the Boy who Became King” by Garry J. Shaw (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Tutankhamun” by Nicholas Reeves (1990, 2023) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun: A Biography” by Martin Bommas (2024) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass (2005) Amazon.com;

“Discovering Tutankhamun: From Howard Carter to DNA” by Zahi Hawass (2013) Amazon.com;

“Amarna Sunset: Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, Ay, Horemheb, and the Egyptian Counter-Reformation” by Aidan Dodson (2009) Amazon.com;

“Pharaohs of the Sun: Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamen” by Rita E. Freed and Yvonne J. Markowitz Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun's Armies” by John Coleman Darnell (2007) Amazon.com; history at time

“The Murder of Tutankhamen: A True Story” by Bob Brier (1998) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun: The Life and Death of a Pharaoh” by David Hamilton Murdoch (1998) Amazon.com;

“King Tutankhamun: The Treasures of the Tomb” by Zahi Hawass (2007) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun, His Tomb and Its Treasures”, lots of images, by I. E. S. Edwards (1976) Amazon.com;

“Egypt's Golden Empire: The Age of the New Kingdom" by Joyce Tyldesley (2011) Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

"The New Kingdom" by Wilbur Smith, Novel (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Temples, Tombs, and Hieroglyphs: A Popular History of Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz (1978, 2009) Amazon.com;

Tutankhamun: a Star Despite His Relative Unimportance

Tutankhamun's tomb opened

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “It is ironic that the Egyptian king who is most famous today was a little known and unimportant pharaoh in his own time. He had no real power, his impact on Egyptian history was trivial, and the modest works carried out during his short reign were taken and renamed by his successors. We have many of the objects he owned and yet we know almost nothing about what sort of person he was. What we do know is fragmentary. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Matthew Shaer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Since Howard Carter discovered the tomb now known as KV62, in 1922, no pharaoh has inspired more “educated guesses” than Tut. He probably came of age during the reign of Akhenaten, a ruler who famously broke from centuries of polytheistic tradition and encouraged the worship of a single deity: Aten, the sun. Born “Tutankhaten”—literally, “the living image of Aten”—Tut is thought to have become king at age 9, and ruled (likely with the help of advisers) until his death at 19 or 20. [Source: Matthew Shaer, Smithsonian Magazine, December 2014 ~~]

“Compared with the long reigns of powerful pharaohs such as Ramses II, Tut’s rule can seem insignificant. “Considering how much attention we pay to Tut,” said Chuck Van Siclen, an Egyptologist at the American Research Center in Egypt, “it’s as if you wrote a history of the presidents of the United States and devoted three long chapters to William Henry Harrison.”... Of the dozens of tombs that honeycomb the Valley of the Kings, Tutankhamun’s is among the least impressive. It’s low-slung and cramped, and since all the treasure currently resides in the Egyptian Museum, in Cairo, there isn’t much to see in KV62, save for the murals and Tut himself. Still, the tomb remains the Valley of the King’s star tourist attraction.” ~~

“Even so, it doesn’t take a Jungian analyst to understand why Tut has captured the world’s attention for so long. Egyptologists had long been forced to make do largely with scraps and fragments, but Tutankhamun’s tomb was found nearly intact and piled high with fantastical treasures. There was the absurdly beautiful burial mask, with its jutting false beard and coiled serpent, poised to strike. There were the rumors of the “curse” that had supposedly claimed the life of Carter’s deep-pocketed backer, Lord Carnarvon. And above all, there was the mystery of Tut’s death—he perished suddenly, it seems, and was placed in a tomb constructed for another king.” ~~

“Tutankhamun has been a projection screen for theories for almost a hundred years,” the Egyptologist Salima Ikram, co-author of a key 2013 paper that sizes up a long century of Tut theorizing, told me over coffee in Cairo. “Some of that, frankly, is researchers’ egos. And some of it is our desire to explain the past. Look, we’re all storytellers at heart. And we’ve gotten very much addicted to telling stories about this poor boy, who has become public property.” ~~

King Tut’s Place in History

If Act I is about tradition and stability, Act II is revolt. When Amenhotep III dies, he is succeeded by his second son,Amenhotep IV — a bizarre visionary who turns away from Amun and the other gods of the state pantheon and worships instead a single deity known as the Aten, the disk of the sun...The end of Akhenaten's reign is cloaked in confusion — a scene acted out behind closed curtains. One or possibly two kings rule for short periods of time, either alongside Akhenaten, after his death, or both. Like many other Egyptologists, I believe the first of these "kings" is actually Nefertiti. The second is a mysterious figure called Smenkhkare, about whom we know almost nothing.

What we know for sure is that when the curtain opens on Act III, the throne is occupied by a young boy: the nine-year-old Tutankhaten ("the living image of the Aten"). Within the first two years of his tenure on the throne, he and his wife, Ankhesenpaaten (a daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti), abandon Amarna and return to Thebes, reopening the temples and restoring their wealth and glory. They change their names to Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun, proclaiming their rejection of Akhenaten's heresy and their renewed dedication to the cult of Amun.

Then the curtain falls. Ten years after ascending the throne, Tutankhamun is dead, leaving no heirs to succeed him. He is hastily buried in a small tomb, designed originally for a private person rather than a king. In a backlash against Akhenaten's heresy, his successors manage to delete from history nearly all traces of the Amarna kings, including Tutankhamun.

Ironically, this attempt to erase his memory preserved Tutankhamun for all time. Less than a century after his death, the location of his tomb had been forgotten. Hidden from robbers by structures built directly above, it remained virtually untouched until its discovery in 1922. More than 5,000 artifacts were found inside the tomb. But the archaeological record has so far failed to illuminate the young king's most intimate family relationships. Who were his mother and father? What became of his widow, Ankhesenamun? Are the two mummified fetuses found in his tomb King Tutankhamun's own prematurely born children, or tokens of purity to accompany him into the afterlife?

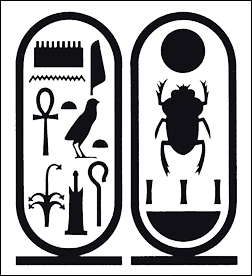

King Tutankhamun's Life

King Tutankhamun was most likely born in 1341 B.C. in Ankhetaten (present-day Tell al-Amarna). He was first called Tutankhaten, meaning “living image of Aten.” He changed his name to Tutankhamun meaning “Living Image of Amun” after he became Pharaoh. His name is perhaps a reference to his perceived duty of restoring the old ways after Akhenaten’s disruptions (Amun was an important god before Akhenaten’s monotheism campaign).

King Tutankhamun was most likely born in 1341 B.C. in Ankhetaten (present-day Tell al-Amarna). He was first called Tutankhaten, meaning “living image of Aten.” He changed his name to Tutankhamun meaning “Living Image of Amun” after he became Pharaoh. His name is perhaps a reference to his perceived duty of restoring the old ways after Akhenaten’s disruptions (Amun was an important god before Akhenaten’s monotheism campaign).

Little is known about Tutankhamun’s childhood. He grew up in Armana, the city established and built by the Pharaoh Akhenaten. Tutankhamun is believed to have received a palace education and probably lived a sheltered and perhaps claustrophobic life. Some have assumed he was raised as a warrior based on weaponry and chariots found in his grave.

It was long thought that he was the son of Lady Kiya, Akhenaten’s second wife, and that she died giving birth to him. He might also have been the brother or half brother of Smenkhkara, his immediate predecessor. Some believe Tut's mother was a commoner and it was great scandal for Tutankhamun's father to marry her. It would have been less scandalous — and in fact the proper thing to do — if he married his mother or sister to keep the royal blood pure.♀

After Akhenaten

The name of Akhenaten’s immediate successor is uncertain. Ann R. Williams wrote in National Geographic History: Nefertiti may have been a co-ruler with her husband at the end of his reign, which lasted about 17 years. She then could have continued to rule in her own right after his death, perhaps even taking a man’s throne name to mask being a female ruler. But there’s another person in the mix here — Smenkhkare. Did he become king upon Nefertiti’s death? Or did Nefertiti not rule at all, and it was Smenkhkare who succeeded Akhenaten? His rise to the top would make sense. He had the right lineage, and he may have been married to Meritaten, the oldest of Akhenaten and Nefertiti’s daughters.[Source: Ann R. Williams, National Geographic History, November 4, 2022]

Akhenaten as a sphinx

Dr Kate Spence of Cambridge University wrote for the BBC: “Akhenaten died in his seventeenth year on the throne and his reforms did not survive for long in his absence. His co-regent Smenkhkare, about whom we know virtually nothing, appears not to have remained in power for long after Akhenaten's death. The throne passed to a child, Tutankhamun (originally Tutankhaten) who was probably the son of Akhenaten and Kiya. The regents administering the country on behalf of the child soon abandoned the city of Akhetaten and the worship of the Aten and returned to Egypt's traditional gods and religious centres. The temples and cults of the gods were restored and people shut up their houses and returned to the old capitals at Thebes and Memphis. [Source: Dr Kate Spence, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Over time, the process of restoration of traditional cults turned to whole-scale obliteration of all things associated with Akhenaten. His image and names were removed from monuments. His temples were dismantled and the stone reused in the foundations of other more orthodox royal building projects. The city of Akhetaten gradually crumbled back into the desert. His name and those of his immediate successors were omitted from official king-lists so that they remained virtually unknown until the archaeological discoveries at Akhetaten and in the tomb of Tutankhamun made these kings amongst the most famous of all rulers of ancient Egypt. |::|

RELATED ARTICLES:

AKHENATEN (1353 B.C. TO 1336 B.C.): HIS LIFE AND MYSTERIES SURROUNDING HIS FAMILY AND DEATH africame.factsanddetails.com ;

AKHENATEN AND MONOTHEISM africame.factsanddetails.com ;

AKHENATEN AND AMARNA africame.factsanddetails.com ;

NEFERTITI: HER LIFE, BEAUTY, BUST AND MARRIAGE TO AKHENATEN africame.factsanddetails.com ;

AKHENATEN'S REIGN (1353 B.C. TO 1336 B.C.) africame.factsanddetails.com

King Tutankhamun Takes the Throne

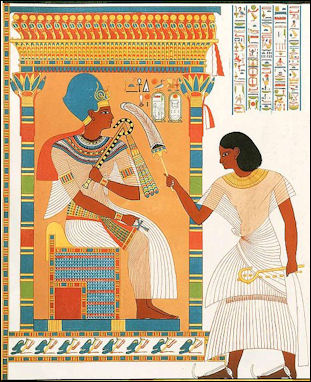

Tutankhamun ascended to throne as the child husband of Akhebaten’s third daughter, a marriage arranged to cement his claim to the throne. He took the throne at age 8 or 9 during a period of great turmoil. It had only been four years since Akhenaten's death. Egypt was on the brink of civil war over monotheism. There was trouble in Syria and with the Hittites. In a limestone bust sculpted after he took the throne, King Tutankhamun wears a khepresh, commonly known as the blue crown.

Tutankhaten was crowned at Memphis about three years after Akhenaten’s death. In his book on finding Tutankhamun’s tomb, Howard Carter wrote the empire under Akhenaten “had crumpled up like a pricked balloon.” Merchants were bitter about the loss of trade. Soldiers “condemned to a mortified inaction were seething with discontent.” Ordinary Egyptians, upset over the loss of their gods, “were changing slowly from bewilderment to active resentment at the new heaven and new earth that had been decreed for them.”

Pharaoh's Palace by Tissot

By the time he took the throne, Tutankhaten who changed his name to Tutankhamun, dropping the Aten and embracing Amun, demonstrating his rejection of Akhenaten’s monotheism and a return to traditional Egyptian religious beliefs. Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “Tutankhamun eventually returned Egypt to its traditional values and Akhenaten’s memory was erased. Later Egyptian historians would refer to him only as “the heretic king.” The city of Akhenaten was abandoned and the court returned to Thebes. Later Horemheb razed the city to the ground and Ramses II reused the stone blocks of its temples for his work at nearby Hermopolis.” [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

It is believed that Tutankhamun was manipulated by the general Horemheb and a courtier named Ay. Some think Ay, who may have been Nefertiti’s father, was responsible for installing Tutankhamun as a puppet pharaoh to heal the divided kingdom. Ay served as a regent while Tutankhamun was growing up. He is believed to have advised Tutankhamun to bring back the pagan religion his father worked so hard to eradicate and move the capital back to Thebes and move the administrative center back to Memphis. Inscriptions say the young king "spent his time making images of the gods.”

Tutankhamun's Rule

Ann R. Williams wrote in National Geographic History: Whoever preceded Tut didn’t rule for long, and the prince became king when he was about nine years old. As an heir apparent, he may have been schooled in all the things a pharaoh would need to do to keep the gods happy and Egypt prosperous. But at such a young age he couldn’t have been ready to rule or to deal with the political and religious chaos left by Akhenaten. Tut must have had advisers, and they apparently were focused on restoring Egypt to what it had been before Akhenaten’s reign. They moved the court back to Thebes, reinstated the old gods, and restored ma’at, the foundational Egyptian concept of order and things as they should be. [Source: Ann R. Williams, National Geographic History, November 4, 2022]

Some scholars credit Tutankhamun with restoring order to the troubled Egyptian kingdom. A stelae raised outside the Amun temple in Karnak apologized for deeds of Akhenaten and boasted of all the things Tutankhamun did to help the kingdom, including “Doubling, tripling and quadrupling the silver, gold, turquoise and lapis lazuli” in the temples.

Egyptologist John Darnell, professor of Near Eastern languages and civilizations at Yale University, told Candida Moss in the Daily Beast that fascination with Tutankhamun is in part due to misconceptions about who he was. “Tutankhamun often appears as the tragic boy king, who died before his reign had really begun” but “in fact, we know he and his administrators were quite active in the south, and his reign sees an at least partially successful military campaign in the northeast.” It’s difficult to say how much of this was down to his advisers, added Darnell, “but his reign is in fact significant, and his tomb — as fantastically rich as it was in never before seen treasures of imperial Egypt — is not the only reason for which we should remember Tutankhamun.” [Source:Candida Moss, Daily Beast, July 21, 2019]

Tutankhamun’s Efforts to Erase Akhenaten’s Monotheistic Reforms

Tutankhamun cartouche Tutankhamun's father is believed to be the pharaoh Akhenaten. According to Live Science: He unleashed a religious revolution that resulted in the Aten, the sun disc, becoming Egypt's main deity. Akhenaten went so far as to destroy images of other gods. Tutankhamun tried to undo his father's changes, turning Egypt's religion back to its traditional focus on multiple gods. [Source: Owen Jarus last updated October 24, 2022]

A study an article published in 2013 in the journal Études et Travaux, suggests that as part of this program of religious normalization Tutankhamun's mummy was prepared so that it literally appeared as the god Osiris. His penis was mummified at a 90-degree angle (recalling Osiris' fertility); his body and coffins were covered with a black goolike liquid that changed the color of the pharaoh's skin; and his heart was removed, recalling the tale of Osiris being cut apart by his brother Seth.

Tutankhamun’s Foreign Military Campaigns

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “During Tutankhamun’s ninth year, Horemheb marched the army into Syria to assist Egypt’s old ally, the Mitannian kingdom of northern Syria, which was embroiled in hostilities with vassals of the Hittites. It was around this time that Tutankhamun died. He was eighteen, and modern medical analysis of his mummy shows that he may have received a blow to the head, but we can only speculate as to whether he was murdered or the victim of an accident such as a fall from his chariot. A number of well-preserved chariots were found in Tutankhamun’s tomb and, like most Egyptian kings, it seems he was an enthusiastic charioteer." [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

Images show Tutankhamun with a pulled bow trampling Nubians under the wheels of his chariot. A Hittite text described an Egyptian attack on Kadesh in present-day Syria during Tutankhamun’s rule. W. Raymond Johnson of the University of Chicago says Tutankhamun “may have led the charge” but most historians discount such claims as propaganda or fiction. More likely Tutankhamun, historians say, spent his time in Memphis with occasional trips to his hunting lodge in Giza and to Thebes for various religion duties at the temples there.

Intrigues After King Tut's Death

Michiko Kakutani wrote in the New York Times, “An emotionally fraught transition from one regime to the next, with no clear-cut successor to the previous ruler. Worries about stability and the maintenance of law and order. Fears about foreign meddling and influence. The army at least temporarily filling the political vacuum and overseeing a transition. This sequence of events — which may sound familiar to those who followed this year’s overthrow of President Hosni Mubarak, Egypt’s ruler of nearly three decades — actually occurred, the scholar Toby Wilkinson said in a recent essay in The Wall Street Journal, more than 3,000 years ago, after the death of the boy-king King Tutankhamen, when the army stepped in to maintain order and act as power broker. [Source: Michiko Kakutani, New York Times March 28, 2011]

After Tutankhamun’s death there was a vacuum of power and major crisis to fill it. Tutankhamuns’s wife Anhesanamun launched a coup and pleaded for help from the Hittites. "My husband is dead, and I have no son," she wrote them. “Send me your son and I will make him king.” The Hittite prince Zannanza was sent to marry her but he was killed — presumably by an assassin — as he entered Egyptian territory. Surviving copies of the correspondence between Anhesanamun and the Hittite king were found over a century ago and the first translation was published in French in 1931, wrote Hans Gustav Güterbock, who was a German-American Hittite expert, in a 1956 article published in the Journal of Cuneiform Studies.

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: The Hittite king, Suppiluliuma I, found it difficult to believe that the Egyptians would allow a Hittite to be pharaoh, but eventually sent one of his sons. Zannanza (also spelled Zananzash)died either along the way or after entering Egypt, Aidan Dodson, an Egyptology professor at the University of Bristol in the U.K., wrote, noting that it's possible Zannanza's death was due to natural causes, as historical records suggest there was an epidemic in the area he would have traveled through. However, it is also possible that Zannanza was assassinated, noting that there may have been a faction in the Egyptian court who opposed a Hittite becoming king that arranged his death. To avoid being sidelined, Ankhesenamun may have tried to get a Hittite husband after Tutankhamun died, Dodson said. "I think it was a means of maintaining her personal power: a foreign husband would be dependent on her," Dodson told Live Science. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, April 1, 2023]

Zahi Hawass wrote in National Geographic, “We know that after Tutankhamun's death, an Egyptian queen, most likely Ankhesenamun, appeals to the king of the Hittites, Egypt's principal enemies, to send a prince to marry her. I believe he was murdered by Horemheb, the commander in chief of Tutankhamun's armies, who eventually takes the throne for himself. But Horemheb too dies childless, leaving the throne to a fellow army commander. The new pharaoh's name was Ramses I. With him begins another dynasty, one which, under the rule of his grandson Ramses the Great, would see Egypt rise to new heights of imperial power.

Tutankhamun had few close relatives left alive when he became pharaoh. Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: He was probably the political puppet of Ay and Horemheb. Under their guidance, he changed his name to Tutankhamun; restored Amenhotep III’s Theban palace; issued a decree restoring the temples, images, and privileges of the old gods; and admitted the errors of Akhenaten’s political and religious policies.” [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

Anhesanamun, Aye and Horemheb had been named as possible murderers of Tutankhamun when such theories were in vogue. Many ruled out Anhesanamun because she seemed to be genuinely close to Tutankhamun and had little to gain from his death since she had not fathered an heir to take his place. Many also rule out Horemheb because he did not seize power after the king’s death. That left Ay he served as a kind of regent when King Tutankhamun was growing up and perhaps got the taste for power and grabbed power by killing the Pharaoh. These theories are highly speculative and been largely thrown out with the latest research on Tutankhamun’s death.

Who Ruled Ancient Egypt after King Tut Died?

Tutankhamen

Ay (ruled 1322-1319) took over as pharaoh after Tutankhamun died by marrying his widow, Anhesanamun, who vanished after the wedding. Ay may have murdered her, perhaps so he could marry another woman. Ay by then was an elderly courtier and possibly Tutankhamun’s uncle. It is not clear whether he chanced into the job or maneuvered his way in. In any case he lasted three or four years and was replaced by army commander Horemheb, who is thought to have trained King Tutankhamun in hunting and fighting and may have killed Ay. Ay was buried in a large tomb, perhaps the one originally built for Tutankhamun. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

Horemheb (ruled 1319-1292) ruled for 27 years and was an able enough leader. It is not clear if he used underhanded methods to achieve power. Whatever the case he took great pains to remove Tutankhamun’s name from the historical record and died childless, paving the way for his army buddy Ramses to take power. Ramses founded a new dynasty.

Tut's death was unexpected, and he left no heirs to the throne. Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: After King Tut died, Ay (also spelled Aya) ascended the throne and ruled for about four years until he died. Ay had been a senior royal official for many years and may have been the father of Nefertiti, the wife of Tut's father, Akhenaten. Evidence of this is found in his title of "God's Father," which may imply that Ay was the father-in-law of Akhenaten, Dodson wrote in his book "Amarna Sunset: Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, Ay, Horemheb, and the Egyptian Counter-Reformation". [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, April 1, 2023]

But Ay wasn't welcomed by the former ruling family. Ancient letters suggest that Tutankhamun's widow, Ankhesenamun, was desperate to prevent Ay from becoming pharaoh and that is why she asked the Hittites for help. Ay may have been related to Ankhesenamun, possibly her grandfather. Even so, if Ay ascended the throne, Ankhesenamun likely understood that he and his son Nakhtmin would relieve her of any power, Dodson said. So her plan to marry a Hittite was "probably pure personal ambition," he said. That said, not everyone agrees that Ankhesenamun actually wrote those letters, said Joyce Tyldesley, an Egyptology professor at the University of Manchester in the U.K. "We have to be very careful not to take the Hittite letter at face value," Tyldesley told Live Science. "Is this really a genuine appeal for a husband — this seems most unlikely." Ankhesenamun "was born royal and could have ruled in her own right," Tyldesley said, noting that it is unlikely Egyptians would have accepted a Hittite prince as pharaoh. "So is the letter perhaps part of a plot, hatched either at the Hittite court or the Egyptian one?"

In any case, with Zannanza dead, Ankhesenamun's plan (hatched by her or someone else) fell through, and Ay took over. Ay's reign was brief, no more than a few years; he built a mortuary temple in Thebes (modern-day Luxor) and had a tomb prepared for himself in the Valley of the Kings. The end of Ay's reign was also controversial. His unrelated successor, Horemheb (also spelled Haremhab), had Ay's tomb desecrated, erasing the names and images of Ay and his wife, Tey (also spelled Tiy), Richard Wilkinson, an Egyptology professor at the University of Arizona, wrote in a chapter of the book "The Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings" (Oxford University Press, 2014). "There seems to have been a power-struggle between Ay's son Nakhtmin and Horemheb, and having won, Horemheb needed to show that Ay had been a 'bad thing,'" Dodson said.Aside from desecrating Ay's tomb, Horemheb released a decree that denounced him. The decree described "the period before his accession as one of disorder and corruption," Dodson said.

Book:"Amarna Sunset: Nefertiti, Tutankhamun, Ay, Horemheb, and the Egyptian Counter-Reformation" by Aidan Dodson, an Egyptology professor at the University of Bristol (American University in Cairo Press, 2009).

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024