Home | Category: Themes, Early History, Archaeology / New Kingdom (King Tut, Ramses, Hatshepsut)

UNLOOTED TOMB OF KING TUTANKHAMUN

Tutankhamun's tomb Excavations of the rock-cut tombs in the Valley of the Kings area began at least in the early 1800s. All were thoroughly looted in antiquity except for one — the four richly appointed chambers of King Tutankhamun. [Source: Ann R. Williams, National Geographic History, November 4, 2022]

The discovery of King Tutankhamun's Tomb is regarded as perhaps the most spectacular archaeological find of all time. This is somewhat surprising because Tutankhamun was by no means one of the great pharaohs. He didn't build a pyramid and he died when he was 18. It just so happened that the room of his tomb where the treasures were found was one of the few in the Valley of the Kings unmolested by looters. The tomb of Ramses II, the greatest pharaoh of all, probably contained a greater horde of treasures but we will probably never know what those treasures were — his tomb was looted only 150 years after his death.

How did Tutankhamun's tomb escape the looting that occurred to every other major tomb. For one it was relatively small and may not have attracted the attention of looters. A grander room with long corridors was being prepared for him but it was never used, perhaps because he died so young, and he was buried in a tomb prepared for someone else. In addition, 200 years after his death, the tomb was covered over by huts of laborers digging the crypt for Ramses , for all intents and purposes hiding it from potential plunderers.

Tutankhamun's tomb can be visited and the treasures found in it are on display in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Book: “In the Valley of the Kings” by Daniel Myerson (2009) recants the story of King Tutankhamun and describes Carter's hunt for his tomb in fairly compelling terms.

RELATED ARTICLES:

TUTANKHAMUN’S TOMB: LAYOUT, CONTENTS, TREASURES, METEORIC IRON africame.factsanddetails.com ;

KING TUTANKHAMUN (KING TUT, 1343-1323 B.C.): HIS LIFE, REIGN AND INTRIGUES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

KING TUTANKHAMUN'S FAMILY: HIS WIFE, DAUGHTERS AND DETERMINING THE IDENTITY OF HIS FATHER AND MOTHER africame.factsanddetails.com ;

TUTANKHAMUN’S POOR HEALTH, DEATH AND MUMMIFICATION africame.factsanddetails.com ;

TUTANKHAMUN’S MUMMY: DNA, CT SCANS, DISCOVERIES africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Tutankhamun: Egyptology's Greatest Discovery” by Jaromír Málek (2009) Amazon.com;

“King Tutankhamun: The Treasures of the Tomb” by Zahi Hawass (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamen” by Howard Carter (1923, 2012) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun, His Tomb and Its Treasures”, lots of images, by I. E. S. Edwards (1976) Amazon.com;

"The Tomb of Tutankhamun Volume 1: Search, Discovery and the Clearance of the Antechamber” by Howard Carter Amazon.com;

“The Tomb of Tutankhamun: Volume 3: The Annex and Treasury” by Howard Carter Amazon.com;

“In the Valley of the Kings: Howard Carter and the Mystery of King Tutankhamun's Tomb” by Daniel Meyerson (2009) Amazon.com;

“Howard Carter: The Path to Tutankhamun” by T. G. H. James (1992) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun's Tomb: The Thrill of Discovery” by Susan J. Allen (2006) Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt” by Kathryn A. Bard Amazon.com;

“Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt” by Steven Blake Shubert and Kathryn A. Bard (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of Egyptology” by Ian Shaw and Elizabeth Bloxam (2020)

Amazon.com;

“Treasures of Egypt: A Legacy in Photographs from the Pyramids to Cleopatra” by National Geographic (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“Egyptology: Search for the Tomb of Osiris” by Dugald Steer (2004) Novel Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com; Wilkinson is a fellow of Clare College at Cambridge University;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

Almost-Discovery of King Tutankhamun’s Tomb

Ann R. Williams wrote in National Geographic History: The story of the discovery of King Tut’s final resting place begins in 1902, two decades before its discovery, when Egypt granted permission to American lawyer and businessman Theodore Davis to dig in the Valley of the Kings. Davis would go on to fund excavations there for more than a decade, discovering and excavating some 30 tombs. He also unearthed tantalizing clues about the young king, whose name was mostly absent from historical records. [Source: Ann R. Williams, National Geographic History, November 4, 2022]

Davis came across two minor deposits containing artifacts with Tutankhamun’s name. One was an embalming cache; the other held embossed, decorative gold from chariots. Davis believed he had found the mysterious pharaoh’s burial, but he was disappointed with the artifacts. Other underwhelming discoveries that he made subsequently convinced him that it was finally time to quit.“I fear that the Valley of the Tombs is now exhausted,” he explained.

According to one report, Davis had come within six feet of Tutankhamun’s tomb. His pivotal decision to give up his concession in the valley on the very brink of success allowed Lord Carnarvon, a wealthy Englishman, to step in in 1914.

Howard Carter, Discovery of Tomb of King Tut

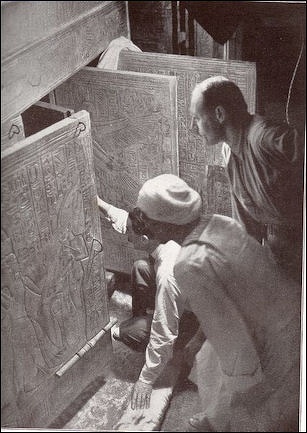

Moment Carter opens Tutankhamun's tomb

The tomb of King Tutankhamun-was discovered by British explorer Howard Carter.The son of a British painter, Carter was born in Norfolk, England and began his career in Egypt at the age 17 copying wall paintings and hieroglyphic inscriptions. In 1899 was appointed the Inspector-General of Monuments in Upper Egypt. The Washington Post described him as — a low-born, little-educated, lonely and slightly-crazed British artist who became one of the greatest Egyptologists of his day."

Carter had no formal training in archaeology but was a talented artist. His keen eye for artifacts helped home earn his position appointed one of two chief inspectors of antiquities in the Egyptian Antiquities Service in 1899. Before that Carter had been scratching out a living selling watercolors to well-heeled tourists. [Source: Tom Mueller, National Geographic, November 2022]

In 1905 the Earl of Carnarvon, who spent the English winters in Egypt, hired Carter to direct archaeological digs. David Kamp wrote in Vanity Fair magazine: “George Herbert, the fifth Earl of Carnarvon. Lord Carnarvon had begun spending winters in Egypt at the turn of the century for health reasons. An early motoring enthusiast, he had a habit of driving too fast and getting into car crashes; as a result, he had damaged his lungs, making it harder for him to endure the cold, damp winters at Highclere, his huge, drafty estate in England. (Highclere now doubles as the title character in television’s Downton Abbey.) An intellectually curious man, Carnarvon took up Egyptology as a hobby and, upon meeting Carter, agreed to finance his digs. [Source: David Kamp, Vanity Fair, March 19, 2013]

Early Archeological Work by Carter

World War I delayed a full-scale search for Tutankhamun’s tomb until the fall of 1917, when improving news from the war allowed resumption of excavations in Valley of the Kings near Luxor . Over the next five years, Carter and a team of Egyptian laborers moved an amazing 150,000 to 200,000 tons of rubble. The work was hard and dirty and especially tough in the scorching desert sun. [Source: Tom Mueller, National Geographic, November 2022 ^^]

By 1922, Carter had been working in Egypt for more than 30 years and had been searching for eight years for something significant — five of them looking for Tutankhamun's tomb. At that time Carter had found a faience cup, a piece of gold foil, and a cache of funerary items which all bore the name of Tutankhamun which raised his hopes that there was still an undiscovered royal tomb in the Valley of the Kings. He had done a systematic search but only found some ancient workmen’s huts at the foot of Rameses VI tomb and 13 calcite jars at the entrance to the tomb of Merenptah.

With little else to show for his efforts after five years of excavating in the Valley, Carnarvon decided it was time to end the search and cut off Carter’s funding . But Carter persuaded Carnarvon to finance just one last season in 1922. Tom Mueller wrote in National Geographic: Five years of pain produced little gain, and Carter’s benefactor grew disillusioned. Perhaps the valley was indeed picked over and played out. In June 1922 Lord Carnarvon summoned Carter to Highclere and announced he was giving up on the valley. Carter pleaded for one more season of digging, even offering to pay for it himself. Lord Carnarvon reluctantly agreed. When Carter arrived back in Luxor on October 28, 1922, the clock was ticking down. Seven days later, a chance discovery lifted his hopes — and soon upended his world.

Discovery of Tomb of King Tut

The tomb of King Tutankhamun was discovered by Carter on November 26, 1922 in the Valley of the Kings. According to one story an opening to the tomb was discovered by a water boy who had dug a hole on a barren hillside under three feet of debris under an ancient workman's hut to keep his personal water bottle cool. The water-carrier stumbled on the corner of a door that was almost completely buried in sand. It opened up to a steep flight of stairs that led to what became known as KV62 (Valley of the Kings 62). A total of 61 royal tombs had been found up until that time, all of them looted.

David Kamp wrote in Vanity Fair magazine: In 1922, Carter, now 49 years old, set out to re-explore a parcel of land in the Valley of the Kings that he had examined two seasons earlier, close to the tomb of Ramses VI, a 20th Dynasty pharaoh who had lived and died roughly 200 years after Tut. The original excavation of this tomb had left an area piled high with ancient rubble, and, near it, a series of huts built by and for the tomb’s laborers. Carter had uncovered the huts, but it had not occurred to him until 1922 that the huts and excavated rock for Ramses VI’s tomb might themselves be covering up an older tomb. [Source: David Kamp, Vanity Fair, March 19, 2013]

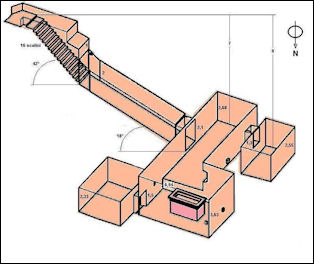

Tutankhamen's tomb map Carter removed the workmen’s huts, which sat at the base of Rameses VI’s tomb. On November 4, just a few days into the new digging season, Carter’s crew of Egyptian workmen, digging near the huts, found a staircase descending into the earth, and, at its base, a sealed door. After four days they found a step that had been cut into the rock and a staircase leading to a blocked entrance. Recalling the member who first laid eyes on the sealed door Carter wrote in his diary, “With excitement growing to a fever he searched the seal impression on the door for evidence of the identity of its owner but could see no name...I needed all my self-control to keep from breaking down the doorway and investigating then and there." Later when the pit was dug deeper, Tutankhamun's name appeared, raising the excitement level another notch.

After Carter made the discovery, he showed incredible restraint and patience. Instead of entering the tomb, he ordered the stairs filled in, to hide the the discovery, placed some of his most trusted workmen as guards and he sent a famous cable to Carnarvon: “At last have made wonderful discovery in Valley a magnificent tomb with seals intact recovered same for your arrival congratulations.” Carter waited for three weeks for Carnavon to arrive from his castle in Hampshire England. It took Carnarvon and his daughter, the 21-year-old Lady Evelyn Herbert, two and a half weeks to reach Luxor by train and boat. To reach the Valley of the Kings, the earl and his daughter crossed the Nile by ferry and rode donkeys to Carter’s excavation site.

Opening of the Tomb of King Tut

The day after Carnarvon arrived the workers again cleared the staircase completely exposing the doorway and revealing several intact seals bearing Tutankhamun’s name. The upper part of the doorway had been damaged, most likely by looters, but the damage appeared to have been repaired. Carnarvon and Carter descended down the stairway and passed through an entrance gallery to the sealed door. When the door was pulled down and all they saw was broken jars and vessels and piles of limestone chips, their hearts sank at the sight of “clear evidence of plundering.” But there was also hole had been refilled with larger, darker rocks, suggesting that the tomb itself had not been disturbed. The passageway was cleared exposing another sealed door and again, there were signs that a hole had been made in the doorway and then resealed.

Carter wrote “With trembling hands I made a tiny breach in the upper left-hand corner. Darkness and blank space, as far as an iron testing-rod could reach, showed that whatever lay beyond was empty, and not filled like the passage we had just cleared. Candle tests were applied as a precaution against possible foul gases, and then, widening the hold a little, I inserted the candle and peered in, Lord Carnarvon, Lady Evelyn and Callender standing anxiously beside me to hear the verdict.

When the second door was taken down and the tomb was entered Carter said he heard "strange rustling, murmuring, whispering sounds" as humidity and new air moved in and began destroying the art and objects. He wrote: “At first I could see nothing, the hot air escaping from the chamber causing the candle flame to flicker, but presently, as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, and gold – everywhere the glint of gold. For the moment – an eternity it must have seemed to the others standing by – I was struck dumb with amazement, and when Lord Carnarvon, unable to stand the suspense any longer, inquired anxiously, “Can you see anything?” it was all I could do to get out the words, “Yes, wonderful things.”“

Inside the Tomb of King Tut

Inside Tutankhamun's tomb, Carter's team found a great treasure, which included gold couches, four gold chariots, a golden throne, alabaster vases and scores of personal items of the king, piled haphazardly as if the room was a mini-storage space. David Kamp wrote in Vanity Fair magazine: “Tutankhamun’s buriers had filled the room with furnishings from his life: beds, baskets, sculpture, games, weapons, chariot wheels. It would take several weeks, with Harry Burton capturing the process moment by moment on film, for the antechamber’s contents to be painstakingly untangled, catalogued, and put into safe storage. A smaller room off the antechamber, which Carter called the annex, was found to contain a similar jumble of objects. [Source: David Kamp, Vanity Fair, March 19, 2013]

The room that Carter had discovered was only the anteroom. Against one end of the chamber stood two life-size statues made of dark wood and gold. Each held a gilded mace and a long gilded staff. Between them was a plastered over door with royal seals. It took two months to clear the treasures out of the tomb and make preparations to open the plastered door.

In the meantime, Kamp wrote: “Word of the “Tut-Ankh-Amen” discoveries, as they were called in the papers, spread quickly around the globe, triggering daily reports from a ravenous press corps, Egyptianchic collections from fashion houses, and the first American wave of Tut-related kitsch, including Tut-branded California lemons, a Hollywood two-reeler comedy called Tut-Tut and His Terrible Tomb, and the Tin Pan Alley ditty “Old King Tut Was a Wise Old Nut,” which contained the couplet “He got into his royal bed, three thousand years B.C. / And left a call for twelve o’clock in nineteen twenty-three.”

Tutankhamun’s tomb included four rooms, now known as the antechamber, annex, treasury, and burial chamber. The tomb was unusually small for a pharaoh, but the rooms were packed with everything he would need to live like a king for all eternity — some 5,400 objects in all.

See Separate Article: TUTANKHAMUN’S TOMB: CONTENTS, ITEMS, TREASURES africame.factsanddetails.com

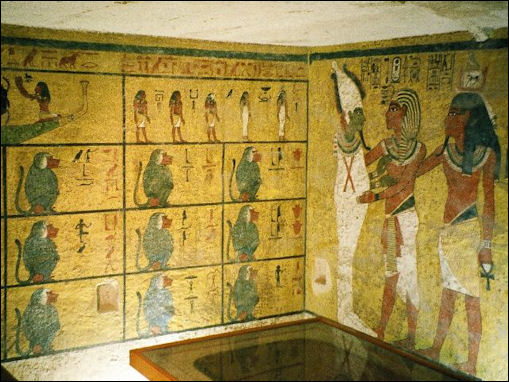

Inside the underground tomb of King Tut

Howard Carter's Team and Careful Archaeological Work

Tom Mueller wrote in National Geographic: Carter had the tomb’s artifacts numbered and photographed, including the life-size statues that guarded the burial chamber. After breaking through the plastered doorway, he found the chamber nearly filled by an ornate, gilded box — Tut’s burial shrine. It was an archaeologist’s dream — and nightmare. Unpacking, cataloging, preserving, and moving the hoard of artifacts — many of which were damaged and fragile — would take a decade of painstaking work and involve an interdisciplinary team of specialists, including conservators, architects, linguists, historians, experts in botany and textiles, and others. The project signaled a new era of scientific rigor in Egyptology. [Source: Tom Mueller, National Geographic, November 2022]

Carter’s friend Arthur “Pecky” Callender, an engineer, built a pulley system to lift heavy objects, installed electric lights, and, when necessary, sat at the tomb entrance with a loaded gun to fend off intruders. Alfred Lucas, a chemist and forensics expert, analyzed the tomb as a crime scene and concluded that two break-ins had occurred in antiquity, soon after Tut was laid to rest. The robbers ransacked some rooms but managed to get away only with smaller, portable items. (Scholars now believe the thieves made off with more than half the royal jewelry.) Harry Burton, who, like Carter, had been an English country lad of modest background, was by 1922 widely recognized as the world’s preeminent archaeological photographer. He set up a makeshift darkroom in a nearby tomb, and his evocative images helped make the discovery and excavation a global media event.

Ann R. Williams wrote in National Geographic History: Howard Carter’s team kept meticulous visual records as it worked in the tomb, including a revealing overhead look at Tutankhamun’s burial chamber that preserves the placement of objects where they were found. After slowly, carefully removing and cataloguing many hundreds of dazzling funerary artifacts, Carter was finally able to open Tut’s nested coffins in late 1925 and gaze upon the mummy. “The youthful Pharaoh was before us at last: an obscure and ephemeral ruler, ceasing to be the mere shadow of a name,” he wrote. “Here was the climax of our long researches.” [Source: Ann R. Williams, National Geographic History, November 4, 2022]

It turns out that looters had broken into the tomb at least twice in ancient times and made off with jewelry and other small objects from the antechamber and had penetrated the burial chamber and treasure room but made off with very little of value. After each occasion the tomb was sealed off by necropolis guards. Comparing what was found with what was listed on inventories, looters made off with about 60 percent of the jewelry. Many of the pieces that were recovered were found in Tutankhamun's sarcophagus, inserted into his mummy wrappings. Most of the furniture, food and drinks jars, games and other artefacts were left untouched.

Opening of the Burial Chamber of King Tut

Tom Mueller wrote in National Geographic: A second great discovery came in February 1923. Carter chipped a hole in the wall of Tut’s burial chamber, held up a flashlight, and peered through. “An astonishing sight its light revealed,” he later wrote, “a solid wall of gold.” The golden wall was, in fact, part of a large, gilded box, or funeral shrine, inside of which were three more shrines and a quartzite sarcophagus. Inside the sarcophagus, Carter would later discover, were three mummy-shaped coffins nested one within the other. Lord Carnarvon joined Carter in the tomb for the much anticipated opening of the burial chamber. Less than two months later he died. [Source: Tom Mueller, National Geographic, November 2022]

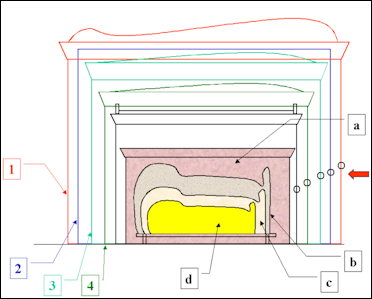

On February 17, 1923, Carter's team broke through sealed, plastered-over door and found the burial chamber itself, almost entirely filled by a golden shrine — 9 feet high, 10¾ feet wide and 16½ feet long — inlaid with panels of brilliant blue faience depicting special symbols that protected the dead. The shrine was actually four shrines, one inside the other. Inside the forth shrine was the sarcophagus made of yellow quartzite with a sculpted goddess spreading protecting arms and wings over its foot.

Inside the sarcophagus was a coffin with a golden effigy of the king in low relief on the lid. On top of that was a wreath of withered flowers that had been placed there almost 3300 years before. Inside the coffin was an undefiled mummy wrapped with 143 pieces of jewelry and the famous blue and gold funerary mask. Inside the tomb were more than 30 golden statuettes of Tutankhamun and various deities. Other treasures included a mirror case in the shape of an ankh and gold pectoral inlaid with semiprecious stones.

Carter later wrote: “It was a sight surpassing all precedent, and one we never dreamed of seeing. We were astonished by the beauty and refinement of art displayed by objects surpassing all we could have imagined — the impression was overwhelming...Three thousand, four thousand years maybe, have passed and gone since human feet last trod the floor on which you stand, and yet, as you note the signs of recent life around you — the blackened lamp, the finger-mark upon the freshly painted surface — you feel as if it might have been but yesterday...Time is annihilated by little intimate details such as these, and you feel an intruder."

“That is perhaps the first and dominant sensation, but others follow thick and fast — the exhilaration of discovery, the fever of suspense, the almost overmastering impulse, born of curiosity, to break down seals and lift lid of boxes, the thought — pure joy to the investigator — that you are about to add a page to history, the strained expectancy — why not confess it? — of the treasure seeker."

Prying King Tut's Mummy From Its Coffin

Undaunted by Lord Carnarvon’s death Carter pressed ahead with the excavation, now supported by Lord Carnarvon’s widow, the Dowager Countess Almina Carnarvon. Tom Mueller wrote in National Geographic: But when Egyptian authorities began taking a more active role in the excavation, Carter stopped work in protest — spurring his new overseers to bar him from the tomb. It would take nearly a year for him to regain access, and only after he and his patroness had renounced all claims to Tut’s burial goods. When work resumed in 1925, Carter focused on disassembling the nested coffins, a herculean task that required clever engineering. The innermost coffin was made of solid gold and weighed almost 250 pounds. Inside lay Tut’s mummified remains, with a stunning mask of gold covering his head and shoulders — an artifact destined to become the symbol of Egypt’s proud past. Yet the man behind the mask would be slow to give up his secrets. [Source: Tom Mueller, National Geographic, November 2022]

Tutankhamun's tomb Carter carefully recorded and catalogued everything he found. He didn't open the third and final coffin, the one containing the mummy and the famous funerary mask, until two years and eight months after the tomb had been discovered. A total of three weeks was spent just cutting away the resin-encrusted wrapping from around the mask. In February 1932, nearly a decade after opening the tomb, Carter finished photographing and cataloguing all the treasures and artifacts he found in Tutankhamun tomb: 5,398 items.

Despite the slow, careful effort, King Tutankhamun's mummy was badly damaged by Carter when he tried to pry off the golden mask and remove the mummy from the coffin. Carter found that the mummy's hardened resins glued it to the bottom of its coffin. Determined to remove it Carter tried prying it out and leaving it in the hot sun. Finally he wrote “the consolidated material had to be chiseled away beneath the limbs and trunk." The head and all the major joints were severed and reassembled on a layer of sand inside a wooden box, where they continue to lie today."

The removal process broke the mummy into 18 pieces. Between 2005 and 2007 the mummy was restored and with great fanfare the face of Tutankhamun was revealed to the public for the first time in November 2007 as he was carefully lifted from a quartz sarcophagus and placed in climate-controlled glass case with his unwrapped head on display for all the world to see.

Curse of the Mummy and the Tomb of King Tut

Carnarvon and Carter became instantly famous after they discovered the tomb. Carter died in 1939, at the age of 64, after having retired full-time to England. Stories about the "Curse of King Tut" materialized shortly after the tomb’s discovery when Carnarvon — and purportedly several members of the expedition — mysteriously died. There were stories that the mummy’s bandages were soaked with cyanide extracted from peach pits, poisoning anyone who touched them, and that an array of booby traps surrounded the tomb.

Carnarvon was bitten by mosquito while relaxing on a Nile riverboat not long after the tomb was discovered. While shaving, he cut open the bite, which became infected. He died in Cairo of sepsis-abetted pneumonia six weeks later. Carnarvon’s death became worldwide news—and the source of the “mummy’s curse” that befalls anyone who disturbs the tomb of an ancient pharaoh. Some scientists suggested that a long dormant disease — perhaps a fungus found in bat guano — might have been released when the tomb was opened. At the moment of Carnarvon's death, it is said, the lights went out in Cairo, and Carnarvon's canary in Egypt and his dog in England died.

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Other deaths attributed to the curse of Tutankhamun include those of Carnarvon’s half-brother, the radiologist who x-rayed the boy-king’s mummy, a member of the excavation tomb who died of arsenic poisoning, and even Prince Ali Kamel Fahmy Bey of Egypt, who was shot to death by his wife on July 10, 1923. For all the speculation, there was no curse on the lintel or walls of the tomb itself. And we should note that Howard Carter himself lived a full decade after the opening of the tomb. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast. January 15, 2017]

Story Behind the Curse of the Mummy

The curse was invented by journalist Arthur Weigalll who was angry that Carnarvon gave the exclusive right of his story to a rival paper. The curse increased the pharaoh's fame and inspired the Boris Karfloff film The Mummy. Of the ten major diggers two were alive 40 years later and another five lived an average of 20 years after the opening. Despite this the story of the curse lives on. Egyptologist Zahal Hawass said that on the day his team did a CT scan of King Tut's mummy he almost had a car accident, a powerful wind suddenly blew up in the Valley of the Kings and the CT machine stopped working for two hours after extraordinary precautions had been made to make sure it was set up properly.

Tutankhamun shrines and sarcophagos Dr Joann Fletcher of the University of York wrote for BBC: “Although ancient Egyptian curses featured in horror fiction dating back to the 19th century, the death of Lord Carnarvon in 1923 following the discovery of Tutankhamen's tomb fixed the belief in such curses' powers firmly in the public's imagination. This was largely fuelled by reports of the 'curse of Tutankhamen' in the press, which was said to claim that 'death shall come on swift wings to him that toucheth the tomb of pharaoh'. [Source: Dr Joann Fletcher, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Although the tomb had contained no such curse, with the story made up simply to sell newspapers, rumours inevitably began to grow. It was reported that various people including Egyptologist Arthur Weigall, novelist Marie Corelli and even the famous medium Cheiro had each warned Carnarvon of impending doom if he continued with the work, whilst crime-writer Arthur Conan-Doyle announced his death to have been caused by unseen 'elementals', put in place by the ancient priests to guard the tomb. |::|

“In the years that followed the discovery, every death with even the most tenuous connection with the tomb was attributed to the curse, although statistics drawn up by American Egyptologist Herbert Winlock in 1934 tell rather a different story. Of the 26 people who had witnessed the opening of the tomb, he noted that only 6 had died over the decade. Only 2 of the 22 who watched the opening of the sarcophagus had since died, and of the 10 present at the unwrapping of the mummy, all were still alive. Nor could anyone explain why Howard Carter remained unaffected by any such curse, a man who had not only 'touched the tomb of pharaoh', but every object in it! Carter himself simply brushed off the idea, adding that 'all sane people should dismiss such inventions with contempt'. |::|

The publication Big Think has attributed the curse of various mummies and dead people to Aspergillus flavus, a fungal mold present within tombs that can infect human lungs. In 1973 10 of the 12 visitors to the tomb of King Casimir IV in Poland (originally sealed in the 15th century) die over the course of the next few months. Popular Science reported: An investigation into the site by a microbiologist unearthed Aspergillus flavus in the tomb, a fungus that can enter the lungs and harm the immune system before potentially spreading throughout the body. A subsequent study explained that the fungus can remain dormant for hundreds of years without losing the ability to infect. That’s a dangerous proposition for those entering a tomb sealed for hundreds of years. [Source: Tim Newcomb, Popular Mechanics, May 9, 2023]

Tutmania in the 1920s

Tom Mueller wrote in National Geographic: The new power of media in a world desperate for diversion after the draining horrors of World War I unleashed a modern wave of Egyptomania that made the boy king a pop-culture celebrity. There were King Tut lemons from California, King Tut cigarette cards and biscuit tins, even a board game called Tutoom in which little metal archaeologists on donkeys searched for treasures. Songs such as “Old King Tut” were Jazz Age hits danced to by flappers wearing cobra headpieces and eye of Horus kohl eyeliner. Egyptian symbols flowed into art deco. Hieroglyphs and cartouches invaded wallpaper, clothing, and furniture fabrics. Egyptian-themed movie theaters opened in some 50 U.S. cities, adorned with gods and sphinxes, papyrus columns, and faux tomb frescoes.[Source: Tom Mueller, National Geographic, November 2022]

When Lord Carnarvon returned to England, he was invited to Buckingham Palace for a personal audience with King George V and Queen Mary, so eager were the royal couple for Tut news. Carnarvon gave the London Times exclusive rights to the unfolding story in return for 5,000 pounds sterling and a percentage of future sales. The deal enraged Egyptian journalists and the international press, whose reporters had to scramble for any scrap of news.

Ann R. Williams wrote in National Geographic History: People wanted to read books and see movies about ancient Egypt, photographs of artifacts recovered from the tomb’s chambers. The jewelers Tiffany & Company, Cartier, and Van Cleef & Arpels created Egypt — themed collections that featured ancient elements such as hieroglyphs, scarabs, and sphinxes. Paris designer Paul Poiret paid homage to Tut by creating couture that highlighted colors, cuts, and patterns from ancient Egyptian works of art. Cosmetics queen Helena Rubinstein — creator of the Valaze Egyptian Mask, which promised to rejuvenate “aging, relaxed faces” — even wore one of Poiret’s Egyptian — themed frocks in a 1923 advertisement for her products. These Egyptian motifs would become an integral part of art deco, the iconic visual language of the Roaring Twenties. [Source: Ann R. Williams, National Geographic History, November 4, 2022]

Tutmania in Egypt and Its Political Impact There

Tom Mueller wrote in National Geographic: Nowhere was Tutmania more powerful than in the pharaoh’s homeland. Egyptians flocked to the Valley of the Kings to see the excavation. Schoolchildren performed plays celebrating the young pharaoh, with props inspired by Burton’s photographs. Political leaders and poets greeted Tutankhamun as a national hero. “He reminds them of their past greatness,” says historian Christina Riggs, “and what their new nation, which only months before had won its independence from Britain, may achieve in the future.” [Source: Tom Mueller, National Geographic, November 2022]

Egyptians saw Tutankhamun’s return to the world as a message from their glorious past. Ahmad Shawqi, the muse of Egyptian independence, addressed Tutankhamun in his poems as the spiritual leader of the Egyptian people. “Pharaoh, the time of self-rule is in effect, and the dynasty of arrogant lords has passed,” Shawqi wrote. “Now the foreign tyrants in every land must relinquish their rule over their subjects!”

Egyptians were claiming sovereignty not only over their laws and economy but over their antiquities as well. Archaeology and empire had long been tightly interwoven, with major excavations funded by European and North American museums, universities, and wealthy collectors such as Lord Carnarvon. In return, funders expected to receive up to half the antiquities discovered, in keeping with a decades-old tradition known as partage, from the French partager, “to share.”

But Egypt’s new leaders would soon insist that all of Tutankhamun’s treasures were part of Egypt’s patrimony and would remain in Egypt. “The new Egyptian government’s decision to keep the collection of Tutankhamun all in Egypt was an important statement of cultural independence,” says Egyptologist Monica Hanna. “This was the first time that we the Egyptians actually started to have agency over our own culture.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2024