Home | Category: Religion and Gods

ANIMAL VERSUS HUMAN FORM OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN GODS

Four sons of Horus

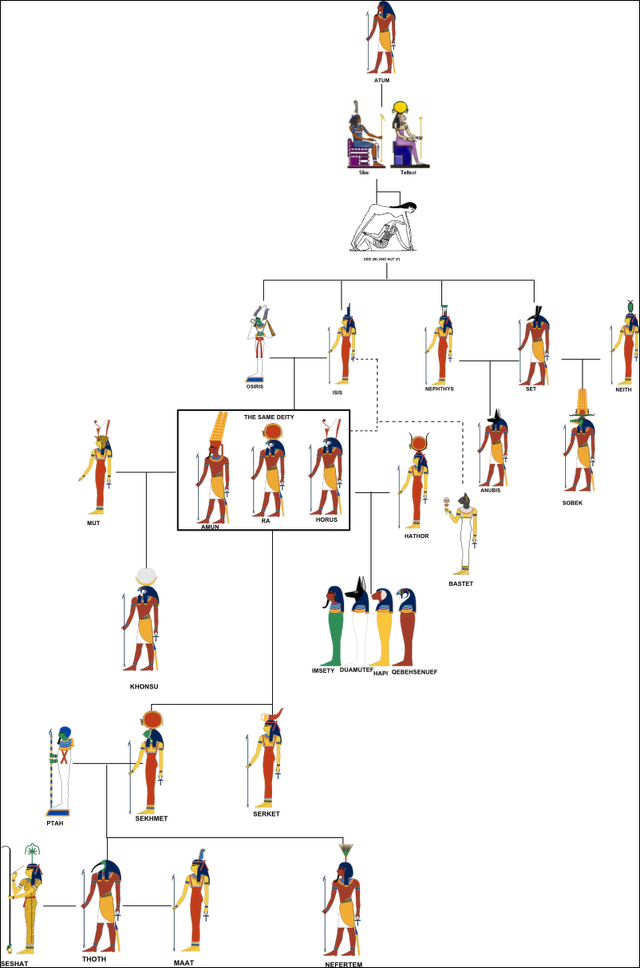

Richard H. Wilkinson of the University of Arizona wrote: “ The visualization of deities in Egyptian culture was manifold and could include a great many different forms ranging from strictly human, to hybrid (or “bimorphic”) and composite varieties. [Source: Richard H. Wilkinson, University of Arizona, Egyptian Expedition, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: ““The physical form taken on by the various Egyptian gods was usually a combination of human and animal, and many were associated with one or more animal species. And an animal could express a deity’s mood. When a god was angry, she might be portrayed as a ferocious lioness; when gentle, a cat. The convention was to depict the animal gods with a human body and an animal head. The opposite convention was sometimes used for representations of a king, who might be portrayed with a human head and a lion’s body, as in the case of the Sphinx. Sphinxes might also appear with other heads, particularly those of rams or falcons.” [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com ^^^]

“Many deities were represented only in human form. Among these were such very ancient figures as the cosmic gods Shu of the air, Geb of the earth, the fertility god Min, and the craftsman Ptah. There were a number of minor gods that took on grotesque forms, including Bes, a dwarf with a mask-like face, and Taurt, a goddess whose physical form combined the features of a hippopotamus and a crocodile.” ^^^

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN GODS AND GODDESSES: TYPES, ROLES, BEHAVIOR AND LETTERS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

LIST OF EGYPTIAN GODS AND GODDESSES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

OSIRIS (GOD OF THE DEAD AND THE AFTERLIFE): MYTHS, CULTS, RITUALS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ISIS (EGYPTIAN GODDESS OF MAGIC AND MOTHERLY LOVE): HISTORY, IMAGES, AND SPREAD OF HER CULT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SETH, THE GOD OF CHAOS: HISTORY, MYTHS, CULT CENTERS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

HORUS, THE FALCON-HEADED PATRON OF KINGS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

THOTH — THE IBIS-HEAD GOD OF WISDOM AND WRITING africame.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN CREATION GODS AND MYTHS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CREATION OF MANKIND AND THE MYTH OF THE HEAVENLY COW africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CHILD DEITIES AND DEIFIED HUMANS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DEMONS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: HISTORY, TYPES, ROLES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

FOREIGN GODS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Search for God in Ancient Egypt” by Jan Assmann (2001) Amazon.com;

“Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many” by Erik Hornung (1982) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt” by Richard H. Wilkinson (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses” by George L. Hart (1986) Amazon.com;

“Gods and Myths of Ancient Egypt” by Robert A. Armour Amazon.com;

“Gods and Men in Egypt: 3000 BCE to 395 CE” by F. Dunand, C. Zivie-Coche and translated by David Lorton (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Encyclopedia of Egyptian Deities: Gods, Goddesses, and Spirits of Ancient Egypt and Nubia” by Tamara Siuda (2024) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life of the Egyptian Gods” by Dimitri Meeks (1993) Amazon.com;

“The Gods of Egypt” by Claude Traunecker (1992) Amazon.com;

“The Gods of the Egyptians, Volume 1" by E. A. Wallis Budge (1969) Amazon.com;

“The Gods of the Egyptians, Volume 2" by E. A. Wallis Budge (1969) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt”

by Geraldine Pinch (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Penguin Book of Myths and Legends of Ancient Egypt” by Joyce Tyldesley (2010) Amazon.com;

”Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Emily Teeter (2011) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Rites, Rituals and Religion of Ancient Egypt” by Lucia Gahlin (2001) Amazon.com;

“Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt” by Rosalie David (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Religion an Interpretation” by Henri Frankfort (1948, 2011) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Gods Speak: A Guide to Egyptian Religion” by Donald B. Redford (2002) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Ancient Egypt: Gods, Myths,and Personal Practice” by John Baines (1991) Amazon.com;

Egyptian Gods with Animal Forms

Richard H. Wilkinson of the University of Arizona wrote: “Hybrid,” or perhaps more accurately “bimorphic” (half-human, half-animal), deities could have the head of either a human or an animal and the body of the opposite type. The head is consistently the essential element of bimorphic deities. Such deities are only partly anthropomorphic in nature as well as in form. They are “the product of a compromise between anthropomorphic thought aimed at abstraction and the appearances of natural forces”. Technically, one might argue that representations of goddesses with wings (Isis, Nephthys, etc.) are hybrid forms, though these are usually classified as fully anthropomorphic. [Source: Richard H. Wilkinson, University of Arizona, Egyptian Expedition, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

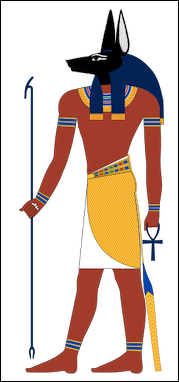

Jackal-headed Anubis

“Composite deities differed from the hybrid or bimorphic forms in that they embodied a combination of several deities or parts thereof, rather than an individual god in a particular guise. They could thus be made up of numerous anthropomorphic or zoomorphic deities and include, in the former case, beings such as multiple-headed and many-armed deities that may have incorporated a combination of as many as a dozen different gods. Yet despite their bizarre appearances, there remains a degree of logic to many of these polymorphic deities.

“This is perhaps most obvious in zoomorphic examples such as the fearsome Ammit and the more benign Tawaret, which were both part hippopotamus, crocodile, and lion, but fused to very different effect. It also seems probable that fused anthropomorphic deities of this type shared some connection or suggested a specific kind of divine identity to the ancient Egyptians, though the connections may not be clear to us today. Syncretized deities such as Ra-Horakhty, Ptah- Sokar-Osiris, and Amun-Ra may also be classified as deities of this type, though they are usually viewed as one deity simply residing within another, and their iconography may stress the characteristics and attributes of only one of the component deities.

“A rigidly fixed iconography for a given god was uncommon, and many deities appeared in several guises....When individual gods or goddesses were depicted in multiple forms, the various forms often reflected the original nature of the deity (for example, Hathor, who could be represented as a cow, as a woman with the head of a cow, or as a woman with a face of mixed human and bovine features). It was also theoretically possible for all deities to be depicted in human form—at least from the New Kingdom—and representations of groups of anthropomorphically depicted gods (including such traditionally zoomorphic or hybrid deities as Anubis) do occur, for example, in some temple settings.”

Epithets of Egyptian Gods

Dagmar Budde of the University of Mainz wrote: “The almost infinite number of epithets applied to Egyptian deities attests to the complex and diverse nature of Egyptian gods. In general, epithets outline a deity’s character, describe his/her physical appearance and attributes, and give information about the cult. Epithets immediately follow the deity’s name and can be made up of several distinct components. In hymns and ritual scenes, epithets often occur in long strings. It is useful to distinguish between epithets that identify a unique aspect of a deity’s personality (“personal epithets”) and epithets that refer to a particular situation or activity (“situational epithets”); in the latter case, the epithet can be applied to multiple deities. [Source: Dagmar Budde, University of Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“Egyptian deities carried epithets that give informationvabout their nature, forms of manifestation, and spheres of influence, as well as genealogical relations and connections with particular locations. In most cases, epithets immediately followed the name. In the course of time, particularly in the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, they grew in complexity. Their length and meaning varied according to context and text medium.

“Whereas a name was normally associated with one deity only, epithets could be transferred to other deities allowed for the creation of new deities. “Personal epithets” (for definition, see below) could be combined with names and titles into a titulary (nxbt, rn-wr). Like the royal titulary, names and epithets of gods were occasionally written in cartouches. This was often the case with Isis, the God’s mother (mwt-nTr), Osiris-Onnophris, and Horus “Who decides the battle of the Two Lands” (wpj-Sat- tAwj). The location of the inscription, a deity’s position and function within the pantheon, and the situational context were crucial factors in the formation of epithets.

“The numerous epithets of Egyptian deities encompass in principle the following three domains : 1) nature and function, 2) iconography (physical characteristics, posture, and attributes), and 3) provenance and local worship; to which can be added the following subdomains: 4) genealogy, 5) status and age, and 6) myths and cosmogonies.”

Nature and Function of Egyptian Divine Epithets

Dagmar Budde of the University of Mainz wrote: “A deity’s nature can be expressed in his/her name, e.g., Amun (“the hidden/secret one”), Khons (“the traveler”), Sakhmet (“the mighty one”), but epithets usually give more information about his/her character and spheres of influence. In the formation of epithets, an ideal image of humans was partly projected onto the world of the gods. Epithets can therefore refer to human traits like wisdom, friendliness, honesty, and a sense of justice. Further themes are the ability to change shapes, to regenerate, and to create, as well as physical strength and weaknesses, freedom of movement, and the closeness to humans. [Source: Dagmar Budde, University of Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“This is illustrated by the following examples: as sun god, Ra is the “Lord of rays” (nb-HDDwt); in his role of moon deity, Khons appears as he “Who repeats rejuvenation” (wHm-rnp). Osiris, the dying and eternally reborn god, was worshipped as “Lord of life” (nb-anx), “Weary of heart” (wrD- jb), and “Who wakes up complete” (rs-wDA), as well as “Master of the course of time (nb-nHH, HqA-Dt). Due to her intelligence, Isis is “Great of magic” (wrt-HkAw) and all-knowing, “Without whose consent no king ascends the throne” (nj-aHa-Hr-nst-m-xmt.s). Horus, the falcon deity and son of Isis and Osiris, is the “Lord of the sky (nb-pt), dappled of plumage, who appears from the horizon”, “Beautiful of face, who shines in the morning and brightens the sky and earth at his rising”. Thoth is the “Judge” (wp), “Who does not accept bribes” (bXn-Snw) and “Who separates the Two Contestants” (wp- rHwj); the latter refers to Horus and Seth as they fight over who will succeed Osiris in office. Foremost, Amun dispenses the breath of life (dj-TAw), but he is also a deity who—like the sun god or Hathor and Maat—“hears prayers” (sDm(t)-sprw/snmHw) and thus serves as a contact for humans. “Epithets generally describe deities in a positive light. Gods act in accordance with maat, are hence “Lord or Lady of Maat” (nb(t)- MAat), overcome chaos and enemies (dr- jsft/sbjw/xftjw), loathe lies (bwt.sn-grg), and everyone rejoices at their sight (Haa-Hr-nb-n- mAA.f/.s). However, Seth is an example of how negative traits can also be expressed. This happens, for instance, when Seth is called “unsuccessful” (wh or wh-sp.f).”

Iconography, Origin and Myths of Egyptian Divine Epithets

ring with the epithet "beloved Amen"

On the iconography (physical characteristics, posture, and attributes) of Egyptian divine epithets, Dagmar Budde of the University of Mainz wrote: “The outer appearance of Hathor is addressed in her epithet “Whose eyes are festively painted”(sHbt-mnDtj), while for child deities, especially in the Roman Period, the epithet “With a beautiful side lock” (nfr/an-dbnt) is characteristic. Posture is addressed in epithets like “With extended arm” (fAj-a, awt-a), which are characteristic for Amun-Min, who is depicted with a raised arm, and for the vulture goddess Nekhbet, who extends her wing in protection. Amun-Min is also “Tall of two plumes” (qA- Swtj), a reference to his double-plumed crown. Amun-Min’s epithet “Who boasts of his perfection” (ab-m-nfrw.f) demonstrates that the transition between domains 1 and 2 can be fluid. It refers on the one hand to the ithyphallic representations of the deity, but on the other hand also to his fertility and potency traits. [Source: Dagmar Budde, University of Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“Origin and local worship. Epithets that establish a connection with a cult site usually consist of two parts and are constructed with “Lord/Mistress (of)” (nb/t), “Ruler (of)” (HqA/t), “Foremost (of)” (xntj/t), or “Dwelling in” (Hrj/t-jb) followed by the name of a location. The formulations Hrj/t-jb and xntj/t generally signal that the deity is the recipient of a local guest cult, whereas nb/t is reserved for the main deity of the area.

“Genealogy. Epithets can also refer to kinship relations. This is most often expressed in a genitival construction with the words “Father (of)” (jtj), “Mother (of)” (mwt), “Son, Daughter (of)” (zA/t), “Brother, Sister (of)” (sn/t), “Child (of)” (nxn, Hwn, xj, Xrd, sfj, etc.), and “Heir (of)” (jwaw) followed by the deity’s name or characteristic epithets.

“Status and age. With adjectives like “great,” “small,” and “first” (wr/t, aA/t, nDs/t, Srj/t, tpj/t), epithets can indicate the status of a deity or his/her position within a hierarchy. Many label the deity as “unique” (wa/t), others distinguish the deity with formulations such as “Whose like does not exist (among the gods)” (jwtj-sn.nw.f/.s, jwtj-mjtt.f/.s, n-wnn-mjtt.f, nn-Hr- xw.s-m-nTrw) and “Beyond whom nobody exists” (jwtj-mAA-Hrj-tp.f/.s), or establish a relationship with a comparative construction like “Who is greater than all other gods” (wr-r- nTrw-nbw). Expressions referring to age such as “Small child” (Xrd-nxn) and “Eldest one” (jAw/smsw) also belong in this category.

“Myths and cosmogonies. Phrases constructed with the lemma SAa (“to begin”) designate creator gods and label the deity as primeval. Others refer to myths (e.g., “Eye of Ra,” jrt-Ra) and cosmogonies (“Who creates sky, earth, water, and mountains,” jr-pt-tA-mw-Dww) and can further be of a very general nature when they characterize the deity as “Great god” (nTr/t- Aa/t, nTr/t-wr/t), “Beneficent god” (nTr/t-mnx/t), or “Noble god” (nTr/t-Sps/t).”

Formation Principles and Sources of Egyptian God Epithets

Aten epithets

Dagmar Budde of the University of Mainz wrote: “Various principles were applied in the formation of epithets. In most cases, epithets consist of two parts. Most common are two nouns in a genitive construction such as “Lord of the sky” (nbt-pt) or “Mistress of all gods” (Hnwt-ntrw-nbw). Other constructions include noun with adjective (e.g., “Great goddess,” nTrt-aAt, “Great sovereign,” jtj-wr, “Perfect youth,” Hwn-nfr), participle with direct object (e.g., “Who breastfeeds her son,” pnqt-zA.s, “Who strikes the foreign lands,” Hw- xAswt), and adjective with object (e.g., “Who has great strength,” wr-pHtj). [Source: Dagmar Budde, University of Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“In comparison, epithets were rarely construed with definite articles like, for example, “The child” (pA-Xrd) as a designation of several child deities or “The menit (necklace)” (tA-mnjt) as an epithet of Hathor. Sporadically, demonstrative pronouns occur, most often for Horus and Seth, who can be designated as “This one” (pn) and “That one,” respectively.

Epithets can be found in almost all text genres, in particular in the religious text corpora such as the Pyramid Texts, Coffin Texts, the Book of the Dead, the underworld books, but also in literary texts, on funerary objects (e.g., stelae, sarcophagi, and coffins), in administrative documents (e.g., inventory lists), legal documents, correspondence, as part of priestly titles and proper names, etc. On stelae, tomb and temple walls, and in papyri, hymns, cult songs, litanies or lists of deities, and mythological texts offer a comprehensive characterization of the addressed deities.

“In the temples, ritual scenes on the walls provided ample room for new, occasionally very long formations and combinations. In particular in the elaborate formulae of the ritual scenes of the Egyptian temples of the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, the redactors devised chains of epithets, which, following a trend in contemporary royal titularies, increased successively in length and variety. The designation aSA/t-rnw, “She/He with many names,” which was associated particularly with Amun, Ra, Osiris, and other creator deities since the New Kingdom.”

Personal and Situational Divine Epithets

Dagmar Budde of the University of Mainz wrote: :In addition to the categories listed above, there exists a distinction between epithets that express the unique personality of the deity irrespective of context or medium, in other words, that establish the deity’s identity, and those that refer to the immediate context. The latter occurs primarily in ritual scenes in which the deity adopts a scene-specific role. Dieter Kurth has coined such epithets “personal” and “situational” epithets, respectively.

element with reliefs pf ears and the epithe Lady of Dendara and the names Taweret and Hathor

“Situational epithets are often ad hoc formations, which could yet develop into formulaic sequences of epithets, for example, in a scene with Hathor in which she is offered a menu-jar with an intoxicating beverage: “Hathor, the Great, Lady of Dendera, Eye of Ra, Lady of the sky, Ruler of all gods, Lady of the Two Lands, Lady of bread, who brews beer, Lady of dance, Ruler of the jba- dance, Lady of drunkenness, Lady of jubilating, Lady of making music, Lady of jubilation, Ruler of joy”. In this case, the personal epithets end with “Ruler of all gods” and are followed by the situational epithets. The same happens in a scene in the Roman Period mammisi in Dendera in which emperor Trajan symbolically offers the horizon to Hathor of Dendera and Horus of Edfu. Following a listing of her personal epithets, the goddess is called here “Powerful one, Daughter of Atum, Rait in the sky, Ruler of the stars, who rises in gold together with him who shines in gold”.

“In ritual scenes, the possibilities are nearly unlimited; multiple relations to the subject matter of the scenes and the offering items are established in the epithets. The deity is oftentimes called their possessor (nb/t, jtj/t, HqA/t, Hnwt), conceiver (SAa), distributor (rdj/t, sSm/t), etc.

“Personal epithets tend to follow the name immediately in apposition, are often of ancient origin, and remain basically unchanged in their structure and predication, as the nature of deities changed little over time even if their sphere of influence could be extended. Examples are Anubis, who as god of the necropolis always carried the epithet “Lord of the sacred land” (nb-tA-Dsr), and Seshat. Moreover, in the latter case the falcon god, the child god, and the goddesses Hathor and Isis incorporate the names and personal epithets of Horus-the- Behdetite (“Great god, Lord of the sky,” nTr-aA nb-pt). The example illustrates that knowledge of mythological connections is often demanded for the reading and correct understanding. This is also required when the appellation “Eye of Ra” (jrt-Ra) is written with a seated falcon god holding a wedjat-eye on his lap. Similarly subtle writings of god names have been discussed by Junker and more recently.

“A phenomenon of late texts is the use of epithets as autonomous names This led to the creation of new, independent, usually locally worshipped deities, as in the Theban region in the temples in El-Qala and Shenhur where “The great goddess” (tA-nTrt-aAt) and “The lady of joy” (nbt-jhj) were worshipped as manifestations of Isis and Nephthys.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024