Home | Category: Religion and Gods

DEMONS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

ram-headed demon

Ancient Egyptian demons were supernatural beings that took many — mainly animal — forms and were thought to live in the twilight zone between divine and real worlds, able to move between them if called upon by either gods or humans. They included protective cobra spirits and knife-wielding turtles who guarded ancient Egyptians in life and death

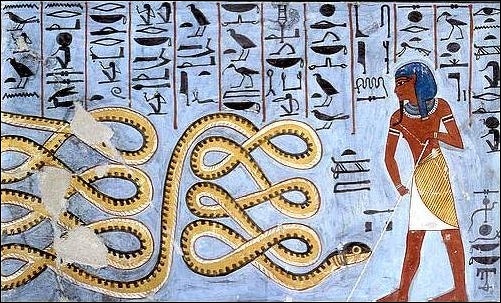

Demons in ancient Egypt could be both malevolent and benevolent. Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: They “were more powerful than human beings but not as powerful as gods. They were usually immortal, could be in more than one place at a time, and could affect the world as well as people in supernatural ways. But there were certain limits to their powers and they were neither all-powerful nor all knowing. Among demons the most important figure was Ammut – the Devourer of the Dead – part crocodile, part lioness, and part hippopotamus. She was often shown near the scales on which the hearts of the dead were weighed against the feather of Truth. She devoured the hearts of those whose wicked deeds in life made them unfit to enter the afterlife. Apepi, another important demon, (sometimes called Apophis) was the enemy of the sun god in his daily cycle through the cosmos, and is depicted as a colossal snake. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Egyptologists know very little about these entities, though it is clear that while demons were capable of causing great harm, they could also be a benevolent force and help maintain maat, or the cosmic order. “They could be something like genies,” says Egyptologist Kasia Szpakowska. “They would come to one’s aid as often as they acted as fearsome, dangerous creatures.” [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2022]

Szpakowska and her colleagues at Swansea University recently completed a project that cataloged as many of these overlooked demons as possible by analyzing figurines and other artifacts that depict the strange beasts. They recorded some 4,000 unique magical beings whom Egyptians worshipped and feared for at least two millennia. It’s possible these demons — who likely numbered far more than 4,000 — were more important to Egyptians’ everyday experience than were the remote gods venerated in the land’s great monuments. “An Egyptian demon is really any divine being not worshipped in a temple,” says Szpakowska. “And they were everywhere.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN GODS AND GODDESSES: TYPES, ROLES, BEHAVIOR AND LETTERS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

FORMS AND EPITHETS OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN GODS AND GODDESSES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

LIST OF EGYPTIAN GODS AND GODDESSES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN CREATION GODS AND MYTHS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CREATION OF MANKIND AND THE MYTH OF THE HEAVENLY COW africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CHILD DEITIES AND DEIFIED HUMANS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

FOREIGN GODS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Daemons and Spirits in Ancient Egypt” by Carolyn Graves-Brown (2018) Amazon.com;

“Gods and Men in Egypt: 3000 BCE to 395 CE” by F. Dunand, C. Zivie-Coche and translated by David Lorton (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt” by Richard H. Wilkinson (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses” by George L. Hart (1986) Amazon.com;

“Gods and Myths of Ancient Egypt” by Robert A. Armour Amazon.com;

“The Complete Encyclopedia of Egyptian Deities: Gods, Goddesses, and Spirits of Ancient Egypt and Nubia” by Tamara Siuda (2024) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life of the Egyptian Gods” by Dimitri Meeks (1993) Amazon.com;

“The Gods of Egypt” by Claude Traunecker (1992) Amazon.com;

“The Gods of the Egyptians, Volume 1" by E. A. Wallis Budge (1857-1934) Amazon.com;

“The Gods of the Egyptians, Volume 2" by E. A. Wallis Budge (1857-1934) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt”

by Geraldine Pinch (2004) Amazon.com;

“Uncovering Egyptian Mythology: A Beginner's Guide Into the World of Egyptian Gods, Goddesses, Historic Mortals and Ancient Monsters” by Lucas Russo (2022) Amazon.com;

”Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Emily Teeter (2011) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Rites, Rituals and Religion of Ancient Egypt” by Lucia Gahlin (2001) Amazon.com;

“Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt” by Rosalie David (2003) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Ancient Egypt: Gods, Myths,and Personal Practice” by John Baines (1991) Amazon.com;

Defining Ancient Egyptian Demons

Rita Lucarelli of the University of Bonn wrote: “Of all Egyptian religious concepts, the notion of “demon” has always been one of the most difficult to interpret for modern scholars. The first difficulty lies in the fact that Egyptian terminology and iconography usually do not distinguish ontologically between demon and deity. In fact, no ancient Egyptian term exists that would translate into “demon” and mark an obvious distinction between deity (nTr) and demon. Nonetheless, the scribal habit to often write the names of inimical beings in red ink and to add the evil or slain enemy determinative to their name shows that Egyptians recognized “malevolent demon” as an ontological category in its own right. It is only by comparing demons and deities with respect to their function, appearance, and status in the created world that we can come to an appreciation of demons in ancient Egyptian thought.” [Source: Rita Lucarelli, University of Bonn, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“According to ancient Egyptian belief, the created world was populated by humans, spirits of deceased humans, deities, and a host of supernatural beings whose identities were never precisely defined. The Egyptian language refers to the first three categories as, respectively, rmT, Ax or mwt, and nTr, but lacks a proper term for the fourth class...Instead of defining “demons” as a uniform group, the Egyptians gave specific names and occasionally physical attributes to its individual classes and members. These names and associated iconography do not so much characterize what these demons are as identify what they do. From the perspective of humans, their behavior can be benevolent and malevolent. Two main classes of demons can be recognized: wanderers and guardians. Wandering demons travel between this world and the beyond acting as emissaries for deities or on their own accord. They can bring diseases, nightly terrors, and misfortune and are therefore basically malevolent. Guardian demons are tied to a specific locality, either in the beyond or on earth, and protect their locality from intrusion and pollution; as such, their function is rather benevolent. In the Late andcPtolemaic and Roman Periods, they came to be regarded as deities in their own right and received cult.”

History of Demons in Ancient Egypt

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Images of demons first began to appear in the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.). Before this time, worship of the gods was highly centralized and mediated by the pharaoh, but during the second millennium B.C., all Egyptians were able to directly participate in religious life. When demons began to appear in documents and depictions officials, as well as the kingdom’s general population, were already actively participating in the worship of the gods. A series of funerary spells known as the Coffin Texts, which were derived from earlier royal funerary texts, became increasingly common in the tombs of ordinary Egyptians. By this time they had as much right to access the afterlife as did the pharaoh. But the journey to the realm of the dead was an arduous one overseen by a bewilderingly diverse set of human-animal hybrid demons. Egyptians imagined the long route to the afterlife as marked by a series of gates over which these demons watched. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2022]

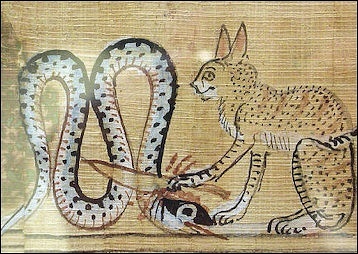

Swansea University Egyptologist Zuzanna Bennett has studied more than 400 demons described in Middle Kingdom Coffin Texts, particularly in one known as the Book of Two Ways. Scenes from these texts are depicted on coffins and act as a map to the underworld. According to the Coffin Texts, in order to pass to the afterlife the deceased was required to recite magical formulas, which served as a kind of password, at each gate. Demons would judge the spells successful — or not. Bennett found that while the forms these demons took may seem strange and monstrous, it’s likely they corresponded to the roles the creatures played at the gates. Baboons, who were thought to be able to talk, were often shown as demons who would render judgment on the deceased. Demons who took the form of animals regarded as stealthy, such as snakes, turtles, or scorpions, would attempt to trip up the deceased as they recited the formulas. Felines and cows, thought of as nurturing creatures, would aid a person in their effort to pass through a gate. Thus, demons were not just obstacles to be overcome, but played an essential role in the divine assessment of each person’s journey to the afterlife.

The 18th Dynasty pharaoh Akhenaten (r. ca. 1349–1336 B.C.) is known for radical religious reforms that elevated the sun god Aten to the status of Egypt’s paramount deity. The pharaoh also ordered a new capital city to be built at the site of Amarna, giving workers only a few years to complete this massive undertaking. Akhenaten’s religious reforms did not outlive him. They were soundly rejected by his successors, who also abandoned Amarna. But Egyptologist Kasia Szpakowska has found that one religious innovation that occurred during Akhenaten’s reign did endure for hundreds of years. She has discovered that clay cobra figurines that became common during the New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1070 B.C.) first appeared in the homes of workers living in Amarna.

Excavations of workers’ cemeteries in the short-lived capital city show that common people living there endured grim conditions. Their bones show evidence of repetitive stress injuries, malnutrition, and trauma that suggest they had been victims of severe punishment. “They must have been suffering from intense anxiety,” says Szpakowska. “Firstly, they were moved to a new capital city, and then they seem to have been subjected to harsh working conditions and corporal punishment.” She suggests that these people, grinding out an existence in a forbidding new location where their traditional beliefs were suppressed, turned to the cobra as a divine protector.

Demons, Deities and Spirits in Ancient Egypt

genie of the Nile flood

Rita Lucarelli of the University of Bonn wrote: “The main difference between demon and deity seems to be that demons received no cult, at least until the New Kingdom. Within the hierarchy of supernatural beings, demons are subordinate to the gods; although they posses special powers, these powers are not universal but rather limited in nature and scope. In general, their influence is circumscribed to one single task, and in certain cases they act under the command of a deity. The available sources do not elaborate on the origin of demons; nor are they explicitly mentioned in creation accounts. However, as they often act as emissaries of deities and are subjected to their will, we may deduce that demons are a creation of the gods. This hypothesis may find support in a formulation in one of the Oracular Amuletic Decrees, referring to protection against certain malevolent “gods who make a wrt- demon against a man”. [Source: Rita Lucarelli, University of Bonn, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“To be distinguished from demons are the roaming dead (mwt) and disembodied spirits (Ax). Although occasionally showing a demonic nature, they are the manifestations of deceased humans in the netherworld. They acquired their supernatural status only after a metaphysical transformation generated by death and ritual. While mwt beings are always malevolent, Ax spirits can be either benevolent or malevolent. Demons, however, are entities in their own right. Nevertheless, demons and spirits of the dead are often listed together in apotropaic spells, because both can be hostile to humans. “Common understanding of the notion of demon, following the Christian reception of the Greek term daimôn in Late Antiquity, sees evil as the main essence of demonic entities as opposed to the notion of angels. Ancient Egyptian religion also relates the existence of demons to “evil”, which is believed to be the realm of chaos outside the created world. However, although this negative connotation cannot be denied in light of the magical texts, the role of demons vis-à-vis the human world remains ambivalent and dependent on their specific context of appearance. In general, it can be stated that demons always act on the borders between order and chaos, maat and isfet. Therefore, in order to define the ancient Egyptian conception of demons, we may call them “religious frontier-striders”, in reference to the apt German term Grenzgängerkonzepte . Some demons bring chaos into the ordered world or act upon the world of the living by command of the divine (e.g., the “wanderers”), whereas others mediate between order and chaos or the sacred and the profane by protecting liminal and sacred places on earth and in the netherworld from impurity (e.g., the “guardians”). In this sense, the Platonic definition of daimôn as an “intermediate being” between gods and mortals also fits the overall picture.”

Snake demons were among the most feared ones. Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: As an animal that fiercely defends its own life, the cobra may have been considered a powerful demon that workers could invoke to protect their own ka, or divine spirit. Some 125 fragments of cobra figurines have been found in laborers’ homes at Amarna and in buildings there such as bakeries. It’s possible many more were discarded by excavators who did not initially recognize the significance of the clay objects, which are often simply made and do not always retain their shape. The tradition of revering these humble idols eventually spread throughout Egypt. Judging by the frequency with which the figurines are found in border forts, it seems soldiers had a special connection to the cobra demon. They may have called upon its support when they found themselves living in strange conditions, far from the familiar comforts of home. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2022]

Types of Demons in Ancient Egypt

Rita Lucarelli of the University of Bonn wrote: “As regards their origin, locality, and forms of appearance, their multifaceted character and the general lack of uniform descriptions in the sources make it impossible to identify a single ontological category of demon. On the basis of nature and location, we can recognize two main classes of demons, which have similar appearance and behavior towards humans: the wanderers and the guardians.[Source: Rita Lucarelli, University of Bonn, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Demons can manifest themselves and act as a single individual but also appear in pairs, in threes, or in a gang. A main distinction exists between demons traveling between the earth and the beyond, so-called “wanderers”, and those that are tied to, and watch over, a place, namely “guardians”.

“Among the wanderers we find many gangs, often of unspecified number, which are controlled by major deities such as Ra and Osiris and act as the executioner of their divine will. They can be agents of punishment on earth and in the netherworld, like the wpwtjw, “the messengers”, which are mentioned in magical and ritual texts from the Middle Kingdom through the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods. In other cases, they cause ineluctable misfortune to humans without orders from the gods. As such they are agents of chaos that persists outside the order of the creation.

“The evil influence of the wanderers can be warded off and kept at the borders of the human world by means of magic. However, it can never be fully destroyed. How exactly their nature was understood remains difficult to establish: they are divine emissaries but occasionally also act independently from the divine will. Moreover, it cannot be stated that these demons are truly subordinate to the gods, since as divine messengers they gain the authority of their senders. In fact, gods can also act as intermediaries or messengers of other deities, for example, Thoth and Hathor, who occasionally serve as messengers of Ra.”

“Guardians represent the second class of demons. Their demonic activity is topographically defined, and their function can be rather benevolent towards those who have the secret knowledge of their names and know how to face them. They are usually attached to a specific place, where their power is truly effective, as, for example, the wrt-demons mentioned in the so-called Oracular Amuletic Decrees of the late 21st Dynasty and later attested in Demotic texts as wry—although in this later form the only reference to a specific place is related to an astrological house. The wrt- demons are often connected to a natural place, which they inhabit, like a pool, a river, a mountain, etc., and from where they assault the passerby. Demons that can be defined by location have also been recognized in other systems of belief, among others in the Hellenistic world.

“The generally aggressive nature of the guardian demons is motivated by the need to protect their abode and is therefore sensible in some measure; as such, they are fundamentally different from disease demons, who invade the human body and other places they do not belong to. They abound in the beyond as guardians of gates and regions of the realm of the dead. They are described and depicted in detail in the spells 144 to 147 of the Book of the Dead and in the netherworld books. The dreadful nature of the guardian demons makes them also suitable for protecting sacred places; accordingly, they took on the role of temple genii in the Late and Ptolemaic Periods. The common Egyptological interpretation of demons as minor deities derives from these protective figures, which are often depicted with an animal head on an anthropomorphic or mummified body and holding knives or other weapons in their hands.”

Diety slaying the demon Apep

Ancient Egyptian Gate Guardians and Demons with Knives

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: When they were first depicted in the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.), demons were often shown gripping fearsome knives to ward off malevolent forces. They not only held these weapons with their hands or forepaws, but, also, in rare instances, with one foot. Egyptologist Kasia Szpakowska has found that by the New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1070 B.C.), a few demons seem to have acquired a new means of wielding these weapons. Szpakowska has identified at least 30 depictions of demons brandishing knives with both of their feet or hindpaws. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2022]

None of the artifacts identify the demons’ names or explain what, exactly, they are doing. But, by studying the placement of the figures, Szpakowska concluded that at least half seem to be engaged in some kind of dance. She believes the dance may be similar to the haka performed by the Maori of New Zealand. The haka, sometimes presented as an intimidating war dance, involves simple steps — stomp to the side, face forward, and then stomp to the other side. The New Kingdom demons may have been engaging in similar moves. Perhaps, thinks Szpakowska, the Egyptians were trying to show these demons as warrior dancers ready to protect their charges with knives bristling from every available limb.

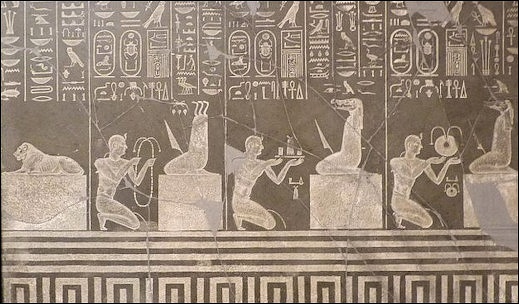

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: A set of rare depictions of demons guarding a gate was discovered at a Saite Period (688–525 B.C.) tomb at the necropolis of Abusir. Belonging to a general named Menekhibenekau, the tomb also contains an enormous sarcophagus that depicts guardian demons. These creatures are often shown on objects or in tomb decorations standing guard by gates to the afterlife, but images of them acting as physical guardians of a tomb are uncommon. Charles University Egyptologist Renata Landgrafova recently analyzed reliefs that decorate the passage entrance to Menekhibenekau’s tomb chamber. She has found that they depict six gates to the underworld, each guarded by three demons acting as a team watching over the portals that Menekhibenekau has to travel through as he makes his way to the afterlife. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2022]

Underworld gate guardians were probably also commonly understood as guardians of the tomb itself. “The fact that the demons are guarding metaphorical gates as well as an actual passage is significant,” says Landgrafova. “This is the only place we have them so obviously serving a dual function.” The demons depicted on the gate to Menekhibenekau’s tomb are the human-animal hybrids common in the Egyptian imagination. One gate is guarded by a turtle-headed demon named “eater of his own excrement,” a lion figure called “he with alert heart,” and a baboon demon known as “great one.” As Menekhibenekau journeyed to the underworld, he would have been required to show himself worthy to pass through these demons’ gates, even as they stood guard over his sarcophagus for eternity.

Ghosts in Ancient Egypt

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Perhaps the most common Egyptian demons were the ghosts of one’s immediate family members. Often the spirits of the recently deceased were invoked in ritual texts that asked for their blessings — what Egyptologists call “letters to the dead.” These texts were likely read aloud during certain rituals, and were inscribed on bowls or other objects left in tombs. The vast majority of these letters were addressed to the dead men, but Leiden University Egyptologist Renata Schiavo has identified a handful of such letters addressed to women. “These letters are rare,” she says, “but they are important documents that give us a sense that women also played an important role in ancestor worship.” [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2022]

One such text Schiavo studied came from the village of Deir el-Medina, the home of artisans who worked in the Valley of the Kings, where pharaohs of the New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1070 B.C.) were buried. The letter was written on a piece of limestone as a rough draft of a text that was perhaps later inscribed on another object. It was written by a scribe named Butehamun and was addressed to the coffin of his dead wife Ikhtay. The text intimates that Butehamun is suffering from some kind of problem that he attributes to the spirit of Ikhtay. He asks the coffin to remind his wife that he has done nothing wrong, that his other deceased relatives still support him, and that she should do so as well.

Other documents discovered at Deir el-Medina record that Butehamun remarried after Ikhtay died. “It’s reasonable to posit that women were invoked in the so-called letters to the dead in order to appease their anger, perhaps because their husbands remarried, or because these women died in dramatic circumstances, for example during childbirth,” says Schiavo. She notes that other rituals are known that involved exorcizing the malevolent spirits of the dead, but this letter, and others like it, suggests a ritual that was intended to heal the relationship between the living and an angry spirit. Despite having remarried, the senders of these letters may have sought to restore the role of these deceased women as protectors of the household, and to invoke their powers as benevolent demons who could help guide their families, even from the afterlife.

The notion that the ka or double of man wandered about after death added to the Egyptian belief in ghosts. E. A. Wallis Budge observed as follows: "According to them a man consisted of a physical body, a shadow, a double, a soul, a heart, a spirit called the khu, a power, a name, and a spiritual body. When the body died the shadow departed from it, and could only be brought back to it by the performance of a mystical ceremony; the double lived in the tomb with the body, and was there visited by the soul whose habitation was in heaven. The soul was, from one aspect, a material thing, and like the ka, or double, was believed to partake of the funeral offerings which were brought to the tomb; one of the chief objects of sepulchral offerings of meat and drink was to keep the double in the tomb and to do away with the necessity of its wandering about outside the tomb in search of food. It is clear from many texts that, unless the double was supplied with sufficient food, it would wander from the tomb and eat any kind of offal and drink any kind of dirty water which it might find in its path. But besides the shadow, and the double, and the soul, the spirit of the deceased, which usually had its abode in heaven, was sometimes to be found in the tomb. There is, however, good reason for stating that the immortal part of man which lived in the tomb and had its special abode in the statue of the deceased was the 'double.' This is proved by the fact that a special part of the tomb was reserved for the ka, or double, which was called the 'house of the ka, ' and that a priest, called the 'priest of the ka, ' was specially appointed to minister the therein." [Source: Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology, The Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Roles, Influences and Manifestations of Demons in Ancient Egypt

Rita Lucarelli of the University of Bonn wrote: “Gods and demons alike, when playing the role of messengers, act with a single, precise aim, which can be directed against humankind. Besides wpwtjw, other gangs of wandering demons acting as divine emissaries are the xAtjw, “the slaughterers”, and the SmAjw, “the wanderers”, attested as early as the Old Kingdom until the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods. They are sent as death- and plague-carriers by furious goddesses like Sakhmet and Bastet. At the end of the year, during the epagomenal days, their influence was considered especially strong on earth, as attested in the Calendars of Good and Bad Days. Starting in the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.), but especially in the temple texts of the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, xAtjw can also be manifestations of the dead decans , whose stars were also seen as disease-bringers. In the Late Period and Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, astrology gained prominence in ancient Egyptian religious thought, and, as a result, certain stars were demonized. For instance, certain astral bodies of the northern constellations, depicted on the astronomical ceilings of temples and tombs, find correspondences in the representations of the demonic inhabitants of the so-called “mounds (jAwt) of the netherworld” described in Spell 149 of the Book of the Dead. [Source: Rita Lucarelli, University of Bonn, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Wandering demons were also considered the cause of certain internal and mental diseases or symptoms, whose pathology was not understood; accordingly, many are mentioned in the magico-medical texts of the Middle Kingdom and later. Among others, the demon Sehaqeq (shAqq) is seen as the cause of headache; he appears in a few Ramesside spells from Deir el-Medina and is once depicted as a young man covering his face. The nsj-demon and his female counterpart nsjt can affect various body parts and even bring death.

“Nightmares (literally rswt Dwt, “bad dreams”) were also understood as caused by demons. Like the disease demons, nightmare demons were believed to enter a human body from the outside and are as such a sub-category of wandering demons. They are said to “descend upon a man in the night”; in this sense, they can be considered the Egyptian equivalent of the Medieval incubi and succubi, although the characterization of sexual assault associated with the latter is not explicit in the Egyptian spells. Depictions of these roaming spirits are nonexistent except for the sketch of the headache demon Sehaqeq mentioned above. Occasionally, spells allude to their evil glance and warn them to turn their face backwards.

“Demonic possession did not only occur during sleep at night; demons could attack or enter the human body also by day when the unlucky passerby approached their abode. Wandering demons also entered and haunted houses, as is evident in a list of the parts of a house to be defended against malevolent influences in a New Kingdom magical spell. They could also move between the earth and the beyond. In the beyond, when acting as guardians of the regions or gates of the netherworld, they could be benevolent towards the deceased, provided the latter possessed the magic to face them. On earth, their actions were mostly malevolent and connected to accidents and plagues—wreaking havoc without distinguishing among the virtuous and wicked.

“In sources dating to the Late Period (712–332 B.C.), and even more so in sources from the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, we notice an increased tendency to interpret daily life accidents and misfortune as resulting from demonic influence. Consequently, to appease them, demons started to receive local and private cults, as did Great-of-Strength (aA pHtj), the first of the seven demons controlled by the god Tutu. Similarly, the xAtjw-demons seem to have received a cult in Ptolemaic Thebes ; they even feature in Demotic personal names with protective and apotropaic meaning. Conversely, certain gods are demonized as they absorb the essence of the creatures they control, like the sphinx god Tutu, who bears the epithet of “master of demons”.

“Much later, in a corpus of Coptic magical spells, we find mention of a real demonic pantheon, consisting especially of demons of the underworld. They are invoked to harm personal enemies. Their punitive function and their specific tasks may well be reminiscent of the demons of Pharaonic times, who were sent to earth from the beyond and belonged to a peripheral world outside creation.”

Nectanebo making offerings to demons

What Ancient Egyptian Demons Looked Like

Rita Lucarelli of the University of Bonn wrote: “The guardians of the netherworld are often provided with an iconography. The other categories of demons, like the already mentioned wrt, are never depicted or physically described. The demonic guardians, on the other hand, are described in much detail and precision, because the deceased must be able to recognize them and know their name in order to overcome their aggression. [Source: Rita Lucarelli, University of Bonn, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Guardian demons have a hybrid human- animal appearance as in other ancient civilizations (Mesopotamia and Greece). In ancient Egypt, the theriomorphic traits of supernatural beings recall their wildest and most fearful aspects, stressing their “otherness” in contrast to the anthropomorphic forms, which denote humanization and membership of the civilized world. Animals often included in the composite bodies of demons are reptiles (especially snakes), felines, and canids; other mammals (donkeys, baboons, hippos, goats, bulls), insects, scorpions, and birds (falcons, vultures) can also be part of a demonic or divine body. This iconography does in essence not differ from the way deities are depicted in their animal and hybrid forms. The similarity is especially striking in the case of apotropaic entities that fight malevolent forces, for example, those represented on the so-called magic wands.

“More typical of demonic iconography are fantastic animals. Sometimes they also show monstrous and grotesque iconographies combining two or more animals or animals and humans into one body. The most popular example is that of Ammut, “the devourer of the dead”, of Spell 125 of the Book of the Dead, who has a crocodile head, a leonine body, and the hindquarters of a hippo. It is indeed in the netherworld that the creativity of the ancient Egyptian theologians in regard to the iconography of demonic beings reached its peak. Especially abundant in the funerary compositions are composite figures of demonic snakes with anthropomorphic legs, multiple heads, and wings, which serve as benevolent and malevolent guardians, like Nehebkau and Rerek. The gigantic python Apep is their archetypal model; however, because of his central and unique role as cosmic enemy of the sun god, Apep stands outside of the categories of gods and demons.

“In the case of gods, hybrid and grotesque iconography symbolizes efficacious apotropaic qualities, as in the case of Bes, the hippo goddesses Ipet and Taweret, and the sphinx god Tutu. This sort of evidence can be compared to the worldwide religious symbolism according to which supernatural beings who were able to transform into animals, like the werewolves and vampires of the Western folklore, were considered “border crossers” and therefore menacing entities for humankind.

“Besides fantastic and composite creatures, the netherworld was also the abode of animals who were considered dangerous (reptiles, insects) or impure on earth (pig, donkey). These belonged conceptually to the manifestation sphere of potentially destructive gods like Seth. A group of spells in the Pyramid Texts aims at warding off snakes, which could be considered enemies of the sun god. Similar spells occur in the Coffin Texts; spells 31 to 42 of the Book of the Dead are devoted to repelling dangerous and impure animals, including snakes. Magical and ritual objects and statues show demonic animals being submitted and controlled by anthropomorphic deities in a protective role; the most wide-spread examples are the New Kingdom ex-votos devoted to Horus-Shed and their later derivation, the Horus-stelae and healing statues, which represent deities that subject a host of dangerous animals. The subordinate role that theriomorphic demons play versus anthropomorphic deities or major humanized demons finds correspondences in other religious traditions, as in the iconography of the Mesopotamian demonic goddess Lamashtu, “mistress of animals”, who is often depicted while holding snakes in her hands and with a scorpion between her legs.”

Male and Female Ancient Egyptian Demons

cat killing Apep

Rita Lucarelli of the University of Bonn wrote: “Most demonic beings are male; female demons occur only rarely in the sources. In general, gender does not give information about the behavior and function of demons, but a few remarks can be made in relation to female demons. They are generally hybrid or animal in form, such as the already mentioned Ammut and the Two Meret snakes, which are the demonic forms of two goddesses mentioned in the Coffin Texts and Spell 37 of the Book of the Dead. An epithet that may refer specifically to female demons is the above mentioned wrt of the Oracular Amuletic Decrees. Although the etymology and precise meaning of the term is unclear, it is remarkable that the same form occurs in combination with the definite article in the phrase tA-wrt, “The Great One”, which is the name for the hippo goddess Taweret and also an epithet for goddesses like Sakhmet or Isis, especially in the Late Period and later. This evidence would confirm the female nature of the wrt-demons and also suggest that the demonic epithet originated from a euphemistic use of the divine one. [Source: Rita Lucarelli, University of Bonn, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“In the Oracular Amuletic Decrees as well as in other apotropaic spells, demonic beings are listed in pairs of male and female as Ax and Axt (“male and female spirit of a deceased”), mwt and mwtt (“male and female dead”), or DAy and DAyt (“male and female opponent”). However, instead of signaling the significance and uniqueness of female demons, such lists are in fact standard formulae that aim to capture the totality of possible dangers and do not really stress the gender issue. Occasionally, spells include the names of the father and mother of a demon, as, for example, the headache demon Sehaqeq, whose parents have names of foreign origin. This suggests that kinship could serve as a classification system for demons; in this respect, Egypt differs from Mesopotamia, where demons are said to have no gender and no families.

“In general, gender does not seem to be relevant with respect to the role demons play on earth and in the netherworld. Perhaps the rare appearance of female demons may reflect the idea that the dynamic, active power of demons is a typically male characteristic. Be this as it may, it must be kept in mind that most gangs of demons were controlled by angry goddesses like Sakhmet or Bastet, who incarnate the power and wild aspect of femininity. Magical texts also mention demons hiding themselves in females, for instance, in an Asiatic woman in the Spell for Mother and Child or in a “dead female who robs as a wailing woman” in a Ramesside spell for protecting different parts of the body.”

Demons and Ancient Egyptian Medicine

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: The ancient Egyptians were sophisticated practitioners of medicine and understood that many contagious diseases could be cured. However, they also realized that some epidemics resulted in symptoms that could not be treated. These illnesses, they believed, were the work of demons controlled by the goddess Sekhmet, who took the form of a lioness and was thought to be responsible for human health. Fayoum University Egyptologist El Zahraa Megahed has recently analyzed a variety of ancient sources, including a New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1070 B.C.) horoscope known as the Calendars of Lucky and Unlucky Days. She has found that Egyptians believed epidemics were caused by demons sent by Sekhmet that manifested as pestilential winds. “Winds are invisible, just as demons were,” says Megahed. “But warm or cold winds can be felt, they can carry a scent, and they can make frightening noises. These winds took on demonic aspects for Egyptians.” [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2022]

Because Sekhmet’s demons were linked with winds and the spread of incurable diseases, individuals suffering during epidemics turned to the goddess’ priests for relief. They prayed to Sekhmet to stop her minions from spreading disease, which was sometimes envisioned, particularly at certain times of the year, as arrows let loose from the mouths of the wind demons. This explanation might have had a real-world basis, as certain diseases are more likely to spread through the air during some months than others. For instance, winds could have carried contagions from the cadavers of animals drowned during the annual Nile flood. The Egyptians may have imagined these winds as arrows sent by Sekhmet’s demon archers that were dangerous to breathe in.

Egyptologist Frank Vink notes that some Middle Kingdom spells intended to be recited during pregnancy and throughout early childhood include a word that scholars interpret as “amulet.” Perhaps, Vink suggests, magic wands were the amulets being cited in these spells. Tauret, the powerful hippopotamus goddess, was associated with childbirth, and the fact that most of the wands were made from hippopotamus tusks might link them to her special role as the protector of mothers and young children. One example of a Middle Kingdom magic wand has a cord still attached to it that could be worn around the neck. It’s possible that mothers and children alike wore these objects as amulets to call upon knife-wielding demons to protect them during the most vulnerable periods of their lives. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2022]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024