Home | Category: Religion and Gods

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN GODS AND GODDESSES

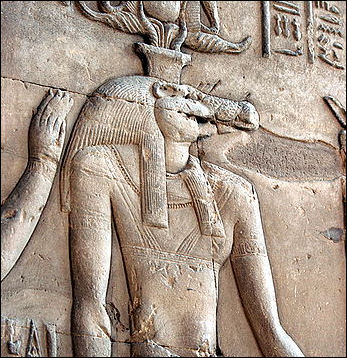

Sobek at Kom Ombo The Egyptians had over 2,000 gods. There were supreme gods, subsidiary ones. There were gods with specific duties, gods associated with specific tasks, gods worshiped in certain areas, gods enshrined in homes and gods associated with natural manifestations such as water and air. Many had totemist and animal elements. Grasping the pantheon of Egyptian gods and their symbols is a difficult task. Gods can be local or universal. Favored gods and their symbols often changed from year to year and region to region.

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: The pantheon of Egyptian gods is filled with mighty human-animal hybrid deities such as Horus, the falcon-headed god of kingship; Anubis, the jackal-headed god of mummification; and the warrior goddess Sekhmet, a divine lioness who possessed healing powers. Ancient priests and scribes left behind millions of textual references to these gods, and their names and titles fill many modern scholarly volumes. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, May/June 2022]

The ancient Egyptians visualized their deities in many ways and these deities took a variety of forms. Some were major deities with great powers and religious significance. Others were demons or genies, or living creatures chosen by ordinary Egyptians as their personal gods. Egyptian goddesses were sometimes pictured topless with a red dress. Goddesses are often distinguished from one another by their headdresses and jewelry around their neck.

The ancient Egyptians practiced polytheism: the worship of many gods. Polytheists have traditionally been looked down upon by practitioners of the great monotheistic religion which worship only a single god — Judaism, Christianity, Islam — as primitive and barbaric pagans. But who knows maybe they had it right. Mary Leftowitz, a classics professor at Wellesley College, argues that a lot of world’s troubles today can be blamed in monotheism. In the Los Angeles Times she wrote, Polytheists “didn’t advocate killing those who worshiped a different gods, and they did not pretend that their religion provided all the right answers.

RELATED ARTICLES:

FORMS AND EPITHETS OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN GODS AND GODDESSES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

LIST OF EGYPTIAN GODS AND GODDESSES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

OSIRIS (GOD OF THE DEAD AND THE AFTERLIFE): MYTHS, CULTS, RITUALS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ISIS (EGYPTIAN GODDESS OF MAGIC AND MOTHERLY LOVE): HISTORY, IMAGES, AND SPREAD OF HER CULT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SETH, THE GOD OF CHAOS: HISTORY, MYTHS, CULT CENTERS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

HORUS, THE FALCON-HEADED PATRON OF KINGS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

THOTH — THE IBIS-HEAD GOD OF WISDOM AND WRITING africame.factsanddetails.com

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN CREATION GODS AND MYTHS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CREATION OF MANKIND AND THE MYTH OF THE HEAVENLY COW africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CHILD DEITIES AND DEIFIED HUMANS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DEMONS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: HISTORY, TYPES, ROLES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

FOREIGN GODS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many” by Erik Hornung (1982) Amazon.com;

“The Search for God in Ancient Egypt” by Jan Assmann (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt” by Richard H. Wilkinson (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses” by George L. Hart (1986) Amazon.com;

“Gods and Myths of Ancient Egypt” by Robert A. Armour Amazon.com;

“Gods and Men in Egypt: 3000 BCE to 395 CE” by F. Dunand, C. Zivie-Coche and translated by David Lorton (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Encyclopedia of Egyptian Deities: Gods, Goddesses, and Spirits of Ancient Egypt and Nubia” by Tamara Siuda (2024) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life of the Egyptian Gods” by Dimitri Meeks (1993) Amazon.com;

“The Gods of Egypt” by Claude Traunecker (1992) Amazon.com;

“The Gods of the Egyptians, Volume 1" by E. A. Wallis Budge (1969) Amazon.com;

“The Gods of the Egyptians, Volume 2" by E. A. Wallis Budge (1969) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt”

by Geraldine Pinch (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Penguin Book of Myths and Legends of Ancient Egypt” by Joyce Tyldesley (2010) Amazon.com;

”Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Emily Teeter (2011) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Rites, Rituals and Religion of Ancient Egypt” by Lucia Gahlin (2001) Amazon.com;

“Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt” by Rosalie David (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Religion an Interpretation” by Henri Frankfort (1948, 2011) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Gods Speak: A Guide to Egyptian Religion” by Donald B. Redford (2002) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Ancient Egypt: Gods, Myths,and Personal Practice” by John Baines (1991) Amazon.com;

Purpose and Organization of Ancient Egyptian Gods

The gods were ordered in a hierarchy. As was true in Mesopotamia local gods also had following in other towns and cities. Most important gods began as local deities and attracted more followers as the influence of their hometowns rose. When a region was conquered, its local gods were often assimilated into the Egyptian cosmological scheme.

The Egyptians believed that gods controlled every aspect of their lives and temples were built to honor them. Gods could be both benevolent and malevolent, good and evil, at the same time. Gods are often pictured holding an ankh and a wassat (a staff) — signifying power. Egyptians believed that gods could die and be reborn. There were even god cemeteries.

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: “Most Egyptian gods represented one principle aspect of the world: Ra was the sun god, for example, and Nut was goddess of the sky. The characters of the gods were not clearly defined. Most were generally benevolent but their favor could not be counted on. Some gods were spiteful and had to be placated. Some, such as Neith, Sekhmet, and Mut, had changeable characters. The god Seth, who murdered his brother Osiris, embodied the malevolent and disordered aspects of the world. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Transformation from Local Gods to Egyptian Gods

some Horuses on a Ramses II relief

Each town, and indeed each village, possessed its own particular divinity, adored by the respective inhabitants, and by them alone. Thus the later town of Memphis was faithful to Ptah, of whom they said, that as a potter on his wheel he had turned the egg from which the world was hatched. The god Atum was the " town god " of Heliopolis; in Hermopolis (Khemenu) we find Thoth, in Abydos Osiris, in Thebes Amun, in Hermonthis Mont, and so on. The goddess Hathor was revered in Dendera, while in Sais the people adored the warlike Neit, who was probably of Libyan origin. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The names of many of these deities show them to be purely local gods, many being originally called after the towns, as, " him of Ombos," " him of Edfu," " her of Bast "; they are really merely the genii of the towns. Many were supposed to show themselves to their worshippers in the form of some object in which they dwelt, e.g. the god of the town Dedu in the Delta (the later Busiris) in the shape of the wooden pillar.

The form chosen was generally that of some animal : Ptah manifested himself in the Apis bull, Amun in the ram, Sobek of the Faiyum in a crocodile, and so on. The Egyptians believed that each place was inhabited by a great number of spirits, and that the lesser ones were subject to the chief spirit; in some instances they formed his suite, his divine cycle; sometimes the\were considered as his family, thus Amun of Thebes had the goddess Mut for his consort, and the god Chons for his son.

As the Egyptian peasants of the different nomes began to feel that they belonged to one nation, and as the intercourse increased between the individual parts of this long country, the old religion gradually lost its disconnected character. It was natural that families traveling from one nome to another should take the gods they had hitherto served to their new homes, and that, like every novelty, these divinities should win prestige with the inhabitants. It is conceivable that the god of a particularly great and mighty town should be believed to exercise a sort of patronage, either politically or agriculturally, over that part of the country dependent upon that centre. When any god had attained this prominent position, and had become d. great god, his worship would spread still farther.

The evolution of Egyptian religion described above took place in prehistoric times. In the oldest records we possess, the so-called pyramid texts, the development was complete, and the religion had essentially the same character as in all after ages. We find a very considerable number of divinities of each rank, the greater with their sanctuaries in various towns, one being always acknowledged as pre-eminent; individual gods are sometimes expressly distinguished the one from the other, sometimes considered as identical; we find a mythology with myths which are absolutely irreconcilable existing peacefully side by side; in short, an unparalleled confusion. This chaos was never afterwards reduced to order; on the contrary, we might almost say that the confusion became even more hopeless during the 3000 years that, according to the pyramid texts, the Egyptian religion " flourished."

Pharaohs and the Gods

The pharaohs were considered to be gods — incarnations of falcon-head Horus, children of the sun god Re. They were descendants of the Amun, regarded as the first Egyptian king, who in turn descended from the sun-god Ra and the falcon god of kingship Horus. Egyptians believed they were given their authority to rule when the world was created.

Referred to as the "lord of all the sun disk encircles," the Pharaoh was believed to be one with the universe and the gods and was regarded as an intermediary between the gods and people on earth. Through them the life force was conveyed from the gods to the people.

A Pharaoh’s coronation was viewed not as "the making of a god but the revealing of a god." According to the ancient Egyptians, the pharaohs were the link between heaven and the earth and their breath kept the two worlds separate.♣

Nile and Ancient Egyptian Gods

There were a number of local Nile gods, including Hapy, the God of the Nile. Sebek (Sobek) was a local crocodile god popular in southern Egypt. He was honored as a god of fertility because the Nile floods brought fertile soil to the farmlands. Live crocodiles were kept at temples honoring Sobek and priests there may have bred crocodiles for ritual use.

John Baines of the University of Oxford wrote: “The Nile, so fundamental to the country's well-being, did not play a very prominent part in the religious life of Egypt. The Egyptians took their world largely for granted and praised the gods for its good features. There was no name for the Nile, which was simply the 'river' (the word 'Nile' is not ancient Egyptian). The bringer of water and fertility was not the river but its inundation, called 'Hapy', who became a god. Hapy was an image of abundance, but he was not a major god. [Source: John Baines, BBC, Professor of Egyptology at the University of Oxford, February 17, 2011 |::|]

cat mummies “Kings and local potentates likened themselves to Hapy in their provision for their subjects, and hymns to Hapy dwell on the inundation's bountiful nature, but they do not relate him to other gods, so that he stands a little apart. He was not depicted as a normal god but as a fat figure bringing water and the products of abundance to the gods. He had no temple, but was worshipped at the start of the inundation with sacrifices and hymns at Gebel el-Silsila, where the hills meet the river, north of Aswan. |::|

“The major god most closely connected with the Nile was Osiris. In myth Osiris was a king of Egypt who was killed by his brother Seth on the river bank and cast into it in a coffin. His corpse was cut into pieces. Later, his sister and widow Isis succeeded in reassembling his body and reviving it to conceive a posthumous son, Horus. |::|

“Osiris, however, did not return to this world but became king of the underworld. His death and revival were linked to the land's fertility. In a festival celebrated during the inundation, damp mud figures of Osiris were planted with barley, whose germination stood for the revival both of the god and of the land. |::|

Ancient Egyptian Gods and Animals

While the pharaohs were described as “half man and half god” the gods were described as “half man and half animal.” Many were depicted with human bodies and animal heads. There were animal cults that venerated bulls and crocodiles.

Some gods were defied animals. Characteristics of gods often matched the characteristics of the animals they were associated with. Storks were connected with soul perhaps because dwelt in the sky. Serpents were associated with deceit. The Hippopotamus god was associated with fertility and safe childbirth. Sekhmet was the lion goddess—“the one who is powerful” — the embodiment of the fiery eye of the sun god Ra. Bes was a goddess who was part dwarf and part lion. She guarded pregnant women and newborn children. Bastet, the cat goddess, was associated with pleasure and was a favorite god who was honored with festivals.

Live animals were often kept in temples. One temple in Saqqara had 60,000 ibises. Symbols of the god Troth, ibises were mummified in greater numbers than any other animal. When these animals died they were mummified, and given funerals, sometimes with elaborate processions. In some cases, animals mummies were placed inside statues of the gods they were connected with.

Anthropomorphic Deities in Ancient Egypt

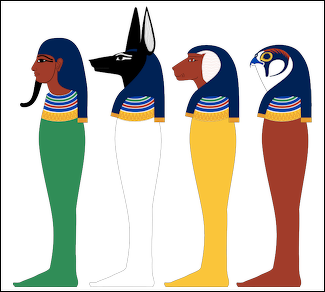

Four sons of Horus

Anthropomorphic deities are gods that have a human form. Richard H. Wilkinson of the University of Arizona wrote: “Although they all shared the common characteristic of exhibiting primarily anthropomorphic identity in their iconographic form and mythological behavior, deities of this class might take fully human, hybrid (“bimorphic”), or composite form. They could include deifications of abstract ideas and non-living things, as well as deified humans—living, deceased, or legendary (such as Imhotep). While a category of “anthropomorphic deities” was not one that the Egyptians themselves differentiated, deities of this type included many of Egypt’s greatest gods and goddesses, and the anthropomorphic form was used more than any other to depict the interactions of humans and the gods in religious iconography.[Source: Richard H. Wilkinson, University of Arizona, Egyptian Expedition, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“Deities manifested in fully human form appear at a fairly early date. Decorated vases from the Naqada II Period (c. 4000 - 3300 B.C.) display a number of apparent divine emblems including two that have been connected with anthropomorphic deities worshipped in the Pharaonic Period: the god Min and the goddess Neith. Thus, both male and female anthropomorphic deities seem to have played a role in Egyptian religious thought before the establishment of the earliest known dynasties, though many clearly originated in the Dynastic Period. It has been suggested that this “anthropomorphization of powers” was associated with a fundamental change in human perception of the world occurring between the time when Predynastic kings still had animal names and a time in which humans began to impose their own identity upon the cosmos.

“While a rigidly fixed iconography for a given god was uncommon, and many deities appeared in several guises, deities with primary anthropomorphic identities (usually those deities whose earliest representations are anthropomorphic) are less frequently depicted in other forms, though exceptions occur. As time progressed, the goddess Isis (depicted anthropomorphically in her earliest representations) was depicted as a serpent, a bird, a scorpion, or other creature, based on her particularly rich mythology.”

Nature of Anthropomorphic Deities

Richard H. Wilkinson of the University of Arizona wrote: “Despite the prevalence of zoomorphic deities in Egyptian thought and the fact that these forms appear to have represented the earliest of Egypt’s divinities, anthropomorphic gods and goddesses were of great importance and embraced a greater number of deities than any other form in developed Egyptian religion. The fluid manner in which anthropomorphic deities were represented in different forms argues against the notion that the human-formed gods were viewed as more important, yet they were nevertheless of fundamental significance in terms of the developed concept of deity itself. It is perhaps not coincidental that anthropomorphic forms were routinely utilized for the generic representation of “god” or “gods” from the Old Kingdom onward, and representations of enneads—which suggest the totality of the gods by their nature and numerical significance— most frequently depict gods anthropomorphically. Deities of this type included many of Egypt’s greatest gods and goddesses and the anthropomorphic form was that in which deities were most frequently depicted in their interactions with humans in religious iconography. [Source: Richard H. Wilkinson, University of Arizona, Egyptian Expedition, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

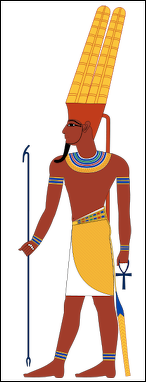

Amun

The preponderance of deities of anthropomorphic form may also have historical implications. Although there were numerous reasons why the nature of Amarna religion was inimical to Egyptian religious orthodoxy, the fact that the greatest of Egypt’s established deities were anthropomorphic, or portrayed as at least partly so in developed Egyptian religion, may have made it less likely that the non- anthropomorphic nature of the Aten would have been widely accepted as a supreme deity. It is certainly clear that the anthropomorphic deities of other ancient Near Eastern cultures were readily absorbed into Egyptian religion, whereas non-anthropomorphic foreign deities usually were not.

“In many cases, the anthropomorphic form was applied to deities whose original identities and roles were abstract or not easily symbolized in the natural world. Thus the so-called “cosmic” gods and goddesses of the heavens and earth such as Shu, god of the air or light, and Nut, goddess of the sky, were generally anthropomorphic in form, as were “geographic” deities, i.e., deities representing specific topographical and geographic features or areas such as mountains, cities, estates, and temples. Though in some cases attributes—such as blue skin for the marsh gods and for Hapi, god of the Nile inundation—might be given to these deities, they are often only identified iconographically by their names. Fecundity figures representing personifications of aspects of non-sexual fertility are minor deities of this type. Other deities—some of them very ancient, such as the fertility god Min—do not fit precisely within these general categories but were also usually manifested in human form. In addition, this category includes elevated humans such as deified living kings, deceased kings— and to some extent their royal kas—as well as some other notable individuals

The essential identity of many anthropomorphically depicted deities can be difficult to ascertain, however. A number of important gods and goddesses were given different names and epithets suggesting multiple identities. Some, such as the deity Neferhotep, clearly fulfilled several distinct roles, sometimes without exhibiting any single identity that could be said to be clearly “primary”. Generally, and often as a result of the fusion of multiple deities, the greater the god or goddess, the wider the range of associations and identities the deity might have.”

Human Characteristics of Anthropomorphic Deities

Richard H. Wilkinson of the University of Arizona wrote: “Not only were deities perceived as taking human forms, but they were also imagined to take on human roles, characteristics, and behavior. The Memphite Theology, which describes the god Ptah as creating with his heart and his tongue (i.e., through deliberative thought and executive speech), underscores the essentially anthropomorphic nature of the god’s actions at even the most transcendent level. Like their human subjects, the Egyptian gods were said to speak, to hear, and to perceive smells and tastes. They could eat and drink (sometimes to excess), they could work, fight, lust, laugh, and cry out in despair. Anthropomorphic deities were clearly viewed as having human needs, and this was, of course, the basis of many aspects of their cults . They could also interact well or poorly and could express anger, shame, and humor— sometimes exhibiting distinctive personality traits as part of their identities. [Source: Richard H. Wilkinson, University of Arizona, Egyptian Expedition, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

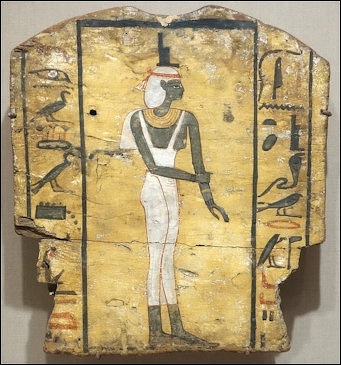

Isis

“The “humanness” of anthropomorphic deities also embraced human social structures: the social relationships inherent in human pairs and family groups were just as much a part of the divine as the human sphere. As time progressed, many of the cults of the major deities were organized into triads of a “father,” “mother,” and “son”— such as that of Amun, Mut, and Khons at Thebes, or Ptah, Sakhmet, and Nefertem at Memphis—and “child deities” such as Horus the child and Ihy were also independently venerated, especially in the first millennium. Many deities were also organized into generational groups, and a great deal of Egyptian religious thought was developed within the parameters of these familial structures.

“The anthropomorphic deities of the Egyptian pantheon also reflected non-kinship societal relationships. Just as the Egyptians were ruled by a king, so there was also a “king of the gods.” Although Ra (or Amun-Ra) was usually given this epithet, the god Osiris could be said to fulfill this role in terms of the afterlife realm and Ptah was often said to be “King of Heaven.” Several deities were given monarchial attributes. Likewise, the essential roles of some deities (for example, Thoth the scribe, and Montu the warrior) reflected aspects of human society. Although such roles bound the respective deities to specific mythological situations, they were not exclusive and did not limit the gods’ power in other settings.Indeed a wide range of roles and powers is particularly associated with anthropomorphic deities, as noted above.

“Ultimately, the very categorization of Egyptian deities as “anthropomorphic” must be mediated through an understanding of the multiple ways in which these deities could be envisioned and depicted, as well as the divine roles and associations that were shared by deities of different forms. The category was, after all, not one that the Egyptians used themselves. Yet the importance of this type of deity in understanding Egyptian religion is not only found in the development of humanity’s view of itself and its gods that seems to have occurred in the earliest stages of Egyptian history (the “anthropomorphization of powers”), but perhaps also in the underlying possibility that at some level the ancient Egyptians may have felt an increasing identification with their anthropomorphic gods—especially in periods of Egyptian history when the phenomena of personal piety and communication with the gods seem to have been more pronounced.”

Ancient Egyptian Letters to Gods

Edward O.D. Love wrote: The “Letters to Gods” comprise an etic analytical category of Egyptian- and Greek-language texts in which individuals petitioned deities, seeking divine intervention in their lives to bring about certain outcomes. Attested from the Late to Roman Periods, from Saqqara to Esna, and inscribed upon papyri, linen, ostraca, wooden tablets, and ceramic vessels, these textual sources are the written testament to ritual practices through which individuals were able to interact directly with the divine to effect change in their lives. Petitioning about a variety of matters (from physical abuse to theft or embezzlement, from cursing people to healing them), the Letters to Gods reveal multiple aspects of the lives of their petitioners — not only their hopes and fears but also their conceptualization of justice and of the divine. [Source: Edward O.D. Love, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2023]

Of the 41 published Letters to Gods, 36 are written in Demotic, four in Greek, and one in Old Coptic. There are also 16 further unpublished manuscripts in Demotic that have been suggested by at least one observer to be Letters to Gods: 10 of these have been confirmed to be Letters to Gods, whereas the remaining six have not, and three of those have since been lost and so cannot be confirmed either way. The Letters to Gods date from the Late to Roman Periods (seventh century B.C. to second century CE) and are attested from Saqqara in the north to Esna in the south .

Maat

Letters to Gods that petitioned deities served by animal cults were deposited in the catacombs and cemeteries of those sacred animals, while those that petition deities without such a cult were deposited in their temple sanctuaries. Three manuscripts in Demotic to Thoth were found in the Ibiotapheion at Hermopolis. Three manuscriptsin Greek to Athena-Neith were found in the Nile perch (lates niloticus) necropolis at Esna. The one example in Demotic to Amenhotep-son-of-Hapu was found in a niche of the main sanctuary used as a chapel for that god at Deir el-Bahri.

It is unclear what proportion of petitioners wrote their own texts, and whether all petitions were commissioned and inscribed at the site where they were subsequently deposited by priests who would have had access to those catacombs, cemeteries, and temple sanctuaries. It is also unclear whether the petitioners were local, or traveled from afar; whether those individuals petitioning particular deities were doing so because they worked within the temple institutions of that particular deity; whether the deity petitioned was the petitioner’s local deity; or whether the deity’s cult center was a center of pilgrimage. Three different petitioners do refer to themselves as holding priestly titles (albeit not necessarily titles relating to the deity they petitioned), and three groups of petitioners refer to themselves as the “servants” of a particular deity (and thereby as individuals working for their cult).

Very little can be said with certainty about the ritual practices that accompanied the deposition of Letters to Gods. As with letters and petitions to worldly recipients, at least the terminology and formulae found in the Letters to Gods suggest that they were written testaments to oral practices, and also that they were brought to their recipients before being recited. There is limited direct evidence of where deities were petitioned. Oracle questions were asked before a divine manifestation, whether cult statue or sacred animal, such as the “Living Apis” (1p anH) at Saqqara, i.e., the Apis Bull, whereupon attending priests would “answer” the questions orally, "interpret" a sacred animal's movements and gestures, or manipulate a deity's cult statue

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Letters to Gods by Edward O.D. Love escholarship.org

Content of Ancient Egyptian Letters to Gods

Edward O.D. Love wrote: A variety of textual characteristics are found within the corpus through which it seems justified to construct and maintain that category. Some examples refer to themselves: two as an an-smy “report”. In around 30 percent of cases the text is described as the xrw-bAk“voice of the servant/humble voice” (i.e., of the petitioner), while nearly 60 percent of cases describe how their petitions are being made “before” the petitioned deity. With the exception of Sa.t nSll, all these terms are found in other types of textual culture, especially in: letters to worldly recipients; petitions to worldly recipients; and oracle/oracular questions/petitions. There is also some overlap in textual characteristics with documents of self-dedication. [Source: Edward O.D. Love, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2023]

Rather at odds with the conventional term “Letters to Gods,” barely a simple majority utilize a direct address to a deity, while only three examples have anything inscribed on their verso, and in only one case does this resemble an address. More specific to the human-divine interaction they evidence, around 30 percent of petitioners supplicate before a deity by describing that deity as “my (great) lord” and nearly 25 percent as “his (wise) master” while several petitioners also refer to themselves as “the” or “your” “servant”.

When described, the practices undertaken by the petitioners encompass Srr “pleading,” Dd “speaking,”smj “petitioning”), and tbH “entreating” before the deity, “petitioning,” “supplicating,” “entreating,” and perhaps “praying”. The circumstances the petitioners find themselves in are also usually described, most commonly utilizing the tropes of “misery” and “suffering” — among a host of other terms describing abuse and deprivation. In order to overcome such circumstances, petitioners commonly entreat the deity for “protection” against, “mercy” regarding, or “rescue” from the aforementioned threat — i.e., future abuse, thefts, and the like. In more specific cases of dispute, petitioners instead entreat that the deity “fulfill” ) their “right” and “deliver” ) “judgment” for them to the accused. A notable subset of Letters to Gods is one in which individuals are cursed, enumerating the retributive rather than restitutive punishment to be delivered upon the accused — disgrace, illness, and deprivation of livelihood. Another subset seeks to heal patients, specifying that they should not die from the suffered illness.

Ultimately, the structure and content of these petitions can vary substantially. This variation ranges from elaborate examples encompassing 30 lines of supplication before a deity with a host of flattering epithets, rhetorical pleas, and a detailed elaboration of the petitioner’s case, to relatively terse addresses and declarations of the outcome sought that span only a few lines. L. BM EA 73786, dating to the Late Period (664 – 332 B.C.) and presumably from Hermopolis (given provenanced comparanda), highlights some of the principal aspects of these petitions: Our great lord, O, Thoth, may you punish WAH-jb -ra -mn retributively! Hear(?) the suffering (of [?]) 6A-tj- pA-Hwtj-nfr with WAH-jb-ra -mn. Suffering, O, Thoth, at the hand of WAH-jb -ra -mn. (I) gave him wheat (and) barley (but) he has not given itback to me, saying: “(I) have protection!” There is no protection for a small man other than Thoth. In this short example, an opening address to the god Thoth is followed by the request to “punish” a named accused “retributively.” The petitioner complains that he gave wheat and barley to the accused, WAH-jb-ra-mn, but that it has not been returned. The accused is cited as shrugging off this charge because he “has protection,” whereas the petitioner, being a “small man,” has no such protection, and therefore only Thoth can protect him.

In many cases the concern that is petitioned about is one and the same as the outcome sought, while in others the outcome is notably different. In the 502 B.C. P. Chicago OI E. 19422 from Hermopolis, the petition first describes the physical abuse and theft suffered: “He has been doing me violence since year 17. He has stolen my money and my wheat. He has had my servants murdered. He has taken for himself everything that (I) have.” Subsequently, the petitioner implores: “Let (me) be protected from PA-Srj-tA-jH(.t)!”.

In P. BM EA 10845, dating to the late Ptolemaic Period and from Hermopolis or Saqqara, the two “underage children” petitioning the Ibis, the Falcon, and the Baboon about their father, who threw them out of their family home after their mother’s death and his subsequent remarriage, entreat: “You should judge us with him” and ultimately “Have our right be fulfilled!”. Their “right” concerns the maintenance they are entitled to from the dowry of their deceased mother, yet they are receiving neither “rations, clothes, nor oil” from their neglectful father. By comparison, petitions concerning embezzlement and/or theft rarely appear to concern restitution, that is, the return of the stolen property, but ratherretribution, that is, the punishment of the accused. This is demonstrated in L. BM EA 73784, dating to the Late Period and presumably from Hermopolis in response to Nx.tj-xnsw-r=w partitioning land from the feeding place of the ibises at Hermopolis — thereby stealing from Thoth by embezzling from his cult — 1r-wAH-jb-rapetitions: “Give his livelihood to me! ... May you have his enemy (i.e., him) fall (and) his livelihood cut off!” What’s more, justification is not always provided in Letters to Gods that enact a curse, with the unnamed petitioner of P. Cairo 31045, dating to the second half of the sixth century B.C. and excavated at Saqqara, almost commanding Osiris-Apis simply to “Protect (me)! Enact retribution against him!”; “Protect me! Have

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024