Home | Category: Religion and Gods

CHILD DEITIES IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Child Horus standing on crocodiles

Dagmar Budde of the University of Mainz wrote: “Child deities constitute a unique class of divinities in Egyptian religion. A child deity is the child member (usually male) in a divine triad, constituting a family of father, mother, and child. The theology of child deities centered on fertility, abundance, and the legitimation of royal and hereditary succession. Child deities grew in importance in temple cult and popular worship in the first millennium B.C. and became particularly prominent in the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods. [Source: Dagmar Budde, University of Mainz, translated from the German by Jacco Dieleman, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Child deities are the child members of divine families, which usually consist of a father, mother, andson. They are represented in human form. Certain other deities occur occasionally in child-form outside family constellations; in these cases, the child imagery serves to emphasize the deity’s potential for cyclical regeneration.

“Child deities were depicted (in text and in visual representation) as infants, toddlers, children, and adolescents. Their birth was believed to secure legitimate royal and hereditary succession, and their subsequent thriving, to manifest a period of prosperity and well-being, in which abundance and continual renewal were guaranteed. A Roman Period ritual scene from Esna, in which the king receives the symbols of regnal years, captures these ideas in the epithets of the local child deity Heka-pa-khered (“Heka-the- child”): “The perfect youth, sweet of love, who repeats the births again and again.” Heka-pa-khered promises the king a long reign and physical regeneration. Thus, despite their child status, these deities became the object of cult, which manifested itself—no earlier than the end of the New Kingdom and particularly in the late Ptolemaic and Roman Periods—in temples dedicated to them, priesthoods, theophoric personal names, ritual and other learned texts, stelae, bronzes, terracotta figurines, scarabs, gems, and other small objects.

“The life-cycle of the sun god provides the basis for the concept of young deities: Ra ages into an old man by day, traverses the nightly darkness in the body of the sky goddess, and is reborn from her body as a child at dawn. Accordingly, a divine child appears sitting on the horns of the Heavenly Cow or, according to other cosmogonies, in the lotus flower.

“In principle, all deities that appear as, or are likened to, children can be linked with such religious imagery. For example, a text in the Roman Period mammisi at Dendara describes the small Ihi-Horus as “perfect lotus flower of gold in the morning, whose sight is as pleasing as that of Ra”. Likewise, Khnum-Ra of Elephantine is characterized in a Roman Period text as a solar child auguring fertility, at whose appearance vegetation. Daughters, unlike mothers, played no distinctive role in these conceptualizations. Even if Hathor acquired power as daughter of Ra and could be addressed as “girl” (Hwnt, sDtjt), she is not to be considered a child goddess.”

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN GODS AND GODDESSES: TYPES, ROLES, BEHAVIOR AND LETTERS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

FORMS AND EPITHETS OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN GODS AND GODDESSES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

LIST OF EGYPTIAN GODS AND GODDESSES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN CREATION GODS AND MYTHS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CREATION OF MANKIND AND THE MYTH OF THE HEAVENLY COW africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DEMONS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: HISTORY, TYPES, ROLES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

FOREIGN GODS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Gods and Men in Egypt: 3000 BCE to 395 CE” by F. Dunand, C. Zivie-Coche and translated by David Lorton (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt” by Richard H. Wilkinson (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses” by George L. Hart (1986) Amazon.com;

“Gods and Myths of Ancient Egypt” by Robert A. Armour Amazon.com;

“The Complete Encyclopedia of Egyptian Deities: Gods, Goddesses, and Spirits of Ancient Egypt and Nubia” by Tamara Siuda (2024) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life of the Egyptian Gods” by Dimitri Meeks (1993) Amazon.com;

“The Gods of Egypt” by Claude Traunecker (1992) Amazon.com;

“The Gods of the Egyptians, Volume 1" by E. A. Wallis Budge (1969) Amazon.com;

“The Gods of the Egyptians, Volume 2" by E. A. Wallis Budge (1969) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt”

by Geraldine Pinch (2004) Amazon.com;

“Uncovering Egyptian Mythology: A Beginner's Guide Into the World of Egyptian Gods, Goddesses, Historic Mortals and Ancient Monsters” by Lucas Russo (2022) Amazon.com;

”Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Emily Teeter (2011) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Rites, Rituals and Religion of Ancient Egypt” by Lucia Gahlin (2001) Amazon.com;

“Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt” by Rosalie David (2003) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Ancient Egypt: Gods, Myths,and Personal Practice” by John Baines (1991) Amazon.com;

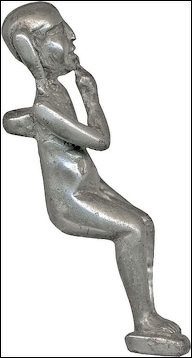

Iconography of Child Deities in Ancient Egypt

Dagmar Budde of the University of Mainz wrote: “The most significant iconographic markers of child deities are the index finger held to the mouth (which Plutarch interprets as a gesture of silence) and the side lock (usually pleated into a braid) at the temple of the head. As a hieroglyphic sign, this lock represents the sound Xrd (“child,” “being young,” “to rejuvenate”), but can by association also be read as rnpj (“to regenerate”) and thus refer again to the principle of cyclical regeneration, which child deities guarantee. Further markers are nudity, possibly symbolizing renewal and fertility, and rolls of belly fat to denote abundance. The child hieroglyph, attested since the Old Kingdom, combines these markers with the seated posture. [Source: Dagmar Budde, University of Mainz, translated from the German by Jacco Dieleman, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

Horus child pendant

“Various crowns identify child deities as legitimate heirs, providers of food and fertility, and cosmic deities. Most frequently occurring are the double crown, the double- feather crown, the hemhem crown, the nemes head-cloth, the atef crown, as well as sun- and moon-disk and skullcap, a uraeus often protruding from the forehead. In the Roman Period, a long, open mantle lies frequently over the shoulders. It occasionally appears to be made of feathers and covers the juvenile body only partially. Some child deities wear a heart amulet that identifies them as heirs and protects them. In their hands they hold the life sign, scepters, musical instruments, or, like human children, a lapwing.

“In sculpture, especially in the Greco- Egyptian terracotta figurines, appear further attributes, often adopted from the Greek cultural sphere, such as cornucopia, grapes, a vessel, or amphora. Like the texts and scenes on temple walls, the attributes of the terracotta figurines express functions and characteristics of the child deities.

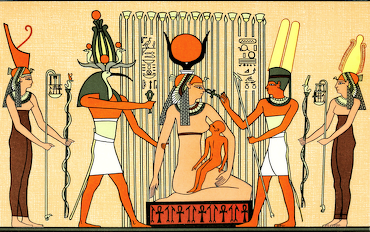

“The child deity appears in a tremendous array of configurations and motifs, the following being particularly popular in relief and sculpture: drinking from mother’s breast and sitting on her lap ; on a lotus flower; between marsh plants; on a block throne or a lion bier; between the horns of the Heavenly Cow: 9); between a pair of snakes; on a potter’s wheel; on the emblem of Uniting the Two Lands; as restrainer of dangerous animals; in the ouroboros (“the snake that bites its tail”); in the solar disk, carried in a bark; in a bark; riding horseback; riding an elephant; in the temple. Many types and motifs are inventions of the Late and Ptolemaic and Roman Periods. With a few exceptions, they have their equivalent in the contemporary hieroglyphic repertoire.”

Functions and Epithets of Child Deities in Ancient Egypt

Dagmar Budde of the University of Mainz wrote: “The functions of child deities were diverse. Apart from their above-mentioned roles— modeled on solar mythology—as providers of life and food and as guarantors of fertility, eternal renewal, and the continuity of legitimate royal and hereditary succession, they also vouchsafed protection against enemies, diseases, and other dangers. They guaranteed a successful birth, regeneration, and, by extension, victory over death. Accordingly, they were popular in afterlife imagery and funerary art—in particular the image of the newborn child on the lotus flower, due to its symbolism of regeneration. They were also believed to possess wisdom and have the power of foresight, because of which they were consulted in oracular procedures. [Source: Dagmar Budde, University of Mainz, translated from the German by Jacco Dieleman, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

Isis suckling Horus

“In temple cult and private devotion, child deities were a source of joy. A Roman Period text in the temple of Esna refers to Heka-pa- khered as “[one] over whom all people rejoice, when they see him; at whose sight all gods and goddesses exult”. The goddess Hathor was particularly appeased by the sight of her child Ihi playing music.

“Epithets bestowed on child deities describe their functions and are furthermore concerned with genealogies, cult places, and iconography. Most epithets consist of an Egyptian term for “child,” such as jnpw, jd, aDd, wnw, wDH, ms, nww/nn, nmHw, nxn, HaA, Hwn, x, Xrd, sA, sfj, sDtj, or Srj, often qualified by adjectives like Sps (“venerable”), nfr (“good, beautiful”), or wr (“great”), and followed by the name of one of the parents. The epithet formula aA wr tpj (“the great, eminent, and first one”) signals the deity’s first position in the hereditary succession. “He with the beautiful braid” refers to the deity’s iconography, while descriptions like “lord of the throne” and “lord of sustenance” refer to the divine child’s qualities as heir and food-provider, respectively. The deity’s functions in cult, particularly in appeasement rituals, are addressed in epithets like “he with sweet lips.” Such epithets are characteristic for Ihi, the musician and dancer, who is also often designated as “the great god”. For the moon child Khons-pa-khered, temple scribes composed epithets such as “who repeats the births of Horus as regenerated boy (Hwn rnp)”, while the solar child could be described poetically as the offspring of Ra, “towards whose sight all plants turn upward”.

“The designation pa khered (“the child”) functions as epithet, but also as component in name formations such as, for example, Horus- pa-khered, Khons-pa-khered, and Heka-pa- khered. In the case of Horus-pa-khered (“Horus-the-child”)—the mythical model and most prominent of child deities—the Egyptian name was transcribed in Greek as Harpokrates. It is important to note that this Graecized name has often been understood by modern scholars, and probably by classical authors, as a generic term for child deities. The use of the Late Egyptian definite article pA signals that the designation was coined relatively late, which demonstrates that Horus-pa-khered, like the other child deities, did not develop into an independent deity before the end of the New Kingdom.”

Theological Development of Child Deities in Ancient Egypt

Dagmar Budde of the University of Mainz wrote: “Already in the Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom, Horus is described as the “young boy with his finger in his mouth”. Here the Horus child defeats the dangers posed by snakes and, in order to benefit from these protective powers in the afterlife, the deceased king identifies with him. Contemporary inscriptions mention a child god from Buto (Nb-Jmt, Jmtj), the writing of whose name includes, as a determinative the hieroglyph of the seated child wearing the Red Crown of Lower Egypt. [Source: Dagmar Budde, University of Mainz, translated from the German by Jacco Dieleman, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Ihi is already mentioned in the Coffin Texts, which begin to appear at the end of the Old Kingdom. His iconography as a child holding musical instruments is first attested at Deir el-Bahri, in the reign of Queen Hatshepsut. He acquired significance at Dendara as the child of Hathor (in addition to Harsomtus-pa-khered) and, cross-regionally, as divine musician and solar child. In accordance with the Egyptian principle of duality, the notion of moon child was conceived in opposition to that of solar child; it was first associated with Khons- pa-khered. The young Heka was invoked in the Judgment after Death and became the child member in the divine triads of Memphis and especially Esna. He is occasionally depicted with the characteristics of a child on stelae of the Libyan and Kushite Periods, but it is not before the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods that he is called Heka-pa-khered in inscriptions.

Pantheistic Bes, god of children

“Religious texts testify that the concept of the child deity goes back as early as the Old Kingdom. Nonetheless, the worship of child deities did not become prominent in temple cult and private devotion before the Third Intermediate Period. The first developments in their theology can be observed at Thebes, where Khons in particular, but also child forms of Horus, such as Horus-pa-khered and Harpara-pa-khered, were worshipped as sons of Amun. Apart from Harpokrates, Ihi, Khons, Heka and Harpara, the following child deities are known: Harsomtus, Somtus, Horus-oudja, Horus-hekenu, Horus-Shu, Ra, Kolanthes, Neferhotep, Shemanefer, Panebtawy, Mandulis, and Tutu. In all these cases, pa-khered (“the child”) can occur as a name component. As an epithet, it is attested for Harsiese, Horus-nefer, and Neper. Ad hoc formations are Sa-menekh-pa-khered and Horakhty-pa-khered. The name component is not attested for Nefertem, the son in the divine triad of Memphis. Moreover, although Nefertem is associated with the lotus, he is never provided with the attributes of a child deity. He is therefore not to be considered a child deity.

“No child deity possessed an iconography unique to that deity alone, but several acquired certain specialized spheres of activity. For example, Harpara-pa-khered, as the child of Rat-tawy and either Amun or Montu, was associated with the sun, and because of his additional association with Thoth, he was, by extension, associated with wisdom as well. Horus-Shed, who is properly to be regarded as an outlier, was particularly popular as vanquisher of ailments and other dangers. In ritual scenes on temple walls, child deities appear as companions to their parents, or by themselves as recipients of offerings—especially food offerings, such as milk, as we see in a libation scene in Esna. Their complexity and popularity is underscored by the existence of groups of seven child-deities, as in the mammisi in Armant and similarly in Dendara, where seven emanations of a single deity, Ihi, occur. In the major temples, particularly in the mammisis, hymns are addressed to them.

“Decisive factors in the development and spread of child-deity theology may have been the pursuit of legitimacy by Egypt’s foreign rulers of the first millennium B.C., and also the hope for blessings (perhaps that of rejuvenation in particular), which private individuals projected onto them. The birth legend provided an important point of departure: whereas in the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.) it was the queen who, by the god Amun, conceived the crown prince, it was, in the first millennium B.C., a goddess who gave birth to a divine child, in whom hope for an ordered cosmos and society was placed. His birth was celebrated every year in the mammisis (his identity depending on the local theology), with the local populace participating in the festivities and revelry. The texts and wall scenes in these buildings concern the modeling of the divine child on the potter’s wheel by Khnum and the young deity’s subsequent enthronement and procession, thus providing insight into the theology of conception, birth, and transfer of rule of child deities and the practices associated with their cults. Priestly titles such as “prophet of the diapers of Khons-pa- khered” and terracotta figurines showing the child deity carried on the shoulders by priests also evoke a general idea of the cultic practices performed in the sanctuaries.”

Deified Humans in Ancient Egypt

Alexandra von Lieven of Freie Universität Berlin wrote: “In ancient Egypt, humans were occasionally the recipients of cult as saints or even deities after their death. Such deified humans could be private persons as well as royalty, men as well as women. The cults were usually of local significance but in certain cases, they rose to national prominence. The phenomenon of human deification is well attested in ancient Egypt and appears to have become more prominent and diversified over time. There existed a hierarchy within the group of deified humans. Local patrons and “wise” scribes seem to have been favored objects of deification. Nevertheless, it remains virtually impossible in most cases to determine why one individual was deified and another was not. [Source: Alexandra von Lieven, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

the pyramid architect Imhotep, a deified human

“The closest analogy in contemporary religions are saints. However, as ancient Egyptian religion was polytheistic, some of these persons were called “gods” or even “great gods” just like the other “real” deities. Nevertheless, there was a hierarchy within the group of deified humans. In some cases, it is quite evident that individuals rose within the hierarchy with the elapse of time after their death. At the beginning, the particular individual only received a slightly more elevated rank than the normal dead. In the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.), such persons were called Ax jqr n Ra, “efficient spirit of Ra”. In the Late Period (712–332 B.C.), they were called Hrj, “superior,” or Hsj, “praised one”. These terms already seem to convey a notion of sainthood. In many cases, the cult never evolved further. However, in more than a few cases it did. The saint developed into a lesser category of god, who was venerated as a local patron. These cults are usually very much connected to a single village or region. More rarely, they developed even further to supraregional and even national scope. The latter was only possible with royal patronage, while the smaller cults seldom attracted any royal attention. The most prominent of these deified persons, who in the end was considered almost on a par with the real gods, was Imhotep— coincidentally, historically the oldest example.

“With this hierarchical development, the historical evolution of deification itself somehow correlates. True deification is first attested in the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.), with Heqaib of Elephantine as prominent examples. While, for example, Isi is called nTr anx, “living god,” it seems that there was still some reluctance to call non-royal deified persons nTr aA, “great god.” Later, however, there is no clearly established hierarchical differentiation in terminology. Thus a Hsj can at the same time be called a nTr aA.

“Deification becomes more and more widespread until in the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods nearly every village seems to have had its deified human (or several of them). In this period, it is not unusual to call a deified human nTr aA or in Greek theos megistos. Therefore, it has been proposed that deification of humans increased in later periods. The phenomenon has been compared to the increase in animal cults.

“In fact, the indigenous terminology shows a clear development. However, there is a certain danger that the seeming dramatic increase in importance and number is somewhat misleading. This is due to the type of sources, which typically survive in larger quantities from the later periods. Unless a cult secured royal patronage, impressive stone monuments are not to be expected. Most temples and shrines of deified humans consisted only of mud-bricks and did not survive into the present. A relatively well-preserved example is the temple of Piyris in Ain Labakha from the Roman Period. Most temples are only attested textually. Again, the textual sources are often not religious documents but administrative texts like inventories of temples or sale contracts of land plots, which mention a temple to pinpoint the location of the sold plot in relation to its neighboring plots.

“In one way or another, the Egyptian cults of deified humans may have influenced subsequent ideas of and practices related to Coptic Christian saints and later Muslim sheiks in Egypt. Even relic veneration seems to have occasionally been part of such cults at least in the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods.”

Human Deity Cults in Ancient Egypt

Alexandra von Lieven of Freie Universität Berlin wrote: “Another major source for deified humans is onomastics. Many such cults can only be deduced from theophoric personal names where the theophoric element is again a proper personal name. The careful study of all the sources suggests that also in the earlier periods, deification of persons was much more widespread than hitherto known. [Source: Alexandra von Lieven, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“While often being inconspicuous in the preserved records, these cults were nevertheless of major social importance and appeal to the respective local population. Deified humans had their own rituals and feasts like other gods and provided help in everyday affairs of their adherents. There is, for example, evidence for processional feasts with barks and palanquins from the New Kingdom. Such processions must have been an important setting for oracles, one of the main functions of deified humans. They decided, for instance, who had stolen a chisel, who rightfully possessed a tomb, or whether a mummification had been performed correctly. They were also called upon to heal and provide children. In the case of Amenhotep I, a sort of mystery play seems to have been celebrated possibly focusing on his death during the feast Preparing the Bed for Amenhotep in the New Kingdom. A list of feast data related to incidents in the life and around the death of Imhotep is attested from the Ptolemaic Period (304–30 B.C.). The reference to beds in a temple inventory in connection with another deified figure speaks in favor of a more widespread prominence of such rites. Equally widespread seems to have been the custom to light torches or lamps in front of a deified person, i.e., his or her statue. A fragmentary calendar from Elephantine gives the dates for “the days of illumination in front of Osiris (of) Nespameti” , archaeological evidence comes from the temple of Piyris in Ain Labakha.

“Statues of deified humans as well as two- dimensional representations can show them either as normal human beings, a good example being the statues of Satabous and Tesenouphis from the Fayum, or with special regalia demonstrating their divine status, for example, the depictions of Petese and Pihor of Dendur in their temple. A third possibility is the depiction of a deified human as another normal deity. This is an iconographic expression of a theological construct clearly attested in a few cases and quite probable in a few others. A good example of this tendency to identify a local deified human with a deity from the established pantheon is the god’s wife of Neferhotep Wedjarenes. Textually well-dated, it is possible to understand how she evolved from a local saint to a hypostasis of Isis within barely 150 years. One might see in such identifications the absorption of the Little Traditions by the Great Tradition.”

“While often being inconspicuous in the preserved records, these cults were nevertheless of major social importance and appeal to the respective local population. Deified humans had their own rituals and feasts like other gods and provided help in everyday affairs of their adherents. There is, for example, evidence for processional feasts with barks and palanquins from the New Kingdom. Such processions must have been an important setting for oracles, one of the main functions of deified humans. They decided, for instance, who had stolen a chisel, who rightfully possessed a tomb, or whether a mummification had been performed correctly. They were also called upon to heal and provide children. In the case of Amenhotep I, a sort of mystery play seems to have been celebrated possibly focusing on his death during the feast Preparing the Bed for Amenhotep in the New Kingdom. A list of feast data related to incidents in the life and around the death of Imhotep is attested from the Ptolemaic Period (304–30 B.C.). The reference to beds in a temple inventory in connection with another deified figure speaks in favor of a more widespread prominence of such rites. Equally widespread seems to have been the custom to light torches or lamps in front of a deified person, i.e., his or her statue. A fragmentary calendar from Elephantine gives the dates for “the days of illumination in front of Osiris (of) Nespameti” , archaeological evidence comes from the temple of Piyris in Ain Labakha.

“Statues of deified humans as well as two- dimensional representations can show them either as normal human beings, a good example being the statues of Satabous and Tesenouphis from the Fayum, or with special regalia demonstrating their divine status, for example, the depictions of Petese and Pihor of Dendur in their temple. A third possibility is the depiction of a deified human as another normal deity. This is an iconographic expression of a theological construct clearly attested in a few cases and quite probable in a few others. A good example of this tendency to identify a local deified human with a deity from the established pantheon is the god’s wife of Neferhotep Wedjarenes. Textually well-dated, it is possible to understand how she evolved from a local saint to a hypostasis of Isis within barely 150 years. One might see in such identifications the absorption of the Little Traditions by the Great Tradition.”

Amenhotep I, a deified human

Who Became Deified Humans in Ancient Egypt and Why

Alexandra von Lieven of Freie Universität Berlin wrote: “A major question is who was deified by whom and why. At least in the earlier periods, it seems that the deification of a person was a grassroots movement with no higher central authority regulating the process. However, in the Ptolemaic Period, a decree by Ptolemy VIII specifies that deified humans were to be buried at the cost of the state treasury. This implies certain rules according to which one could be sanctified. [Source: Alexandra von Lieven, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“As to the types of persons concerned and the reasons for their deification, there is a major problem. Of many of the attested deified persons nothing or at least not enough is known about them as individuals. Furthermore, only one text ever gives an explicit reason for the deification, thus one can only speculate. Interestingly, the text in question, a hymn to Pramarres inscribed on a temple door in Medinet Madi, is written in Greek. One of the reasons given is Pramarres’ ability to talk to animals. Clearly, this is not something one would have expected. It must be a reference to a historical romance like those well attested in Demotic from contemporary temple libraries from Tebtunis and Soknopaiou Nesos, respectively.

“At least for the social groups concerned, it is possible to give some rough indications. Apart from royalty, they were typically wise people, for example, authors of wisdom literature and the like or local leaders like nomarchs. The special deification of individual kings and queens like Amenhotep I and Ahmose- Nefertari is not to be confused with the general idea of a semi-divine status of the king or his ka as part of the royal ideology. “Finally, persons who died a special death by “divine agency,” for example, by drowning or being killed by a snake or crocodile, could also be deified. The latter category is the one labeled “praised ones” (Hsj.w) by the Egyptians themselves. It seems that death by a divine creature like a crocodile was regarded as a special grace. In that respect, the cult of Antinoos was not an anomaly, but indeed keeping within Egyptian tradition.

“Apart from a few rare royal cases of self- deification during lifetime, deification is usually conferred only as a posthumous honor. While the majority of deified humans are men, a certain number of women, both royal as well as private persons, are attested. In a few exceptional cases, even small children seem to have been deified, for example, the New Kingdom prince Ahmose Sapair, or possibly also Nespameti from Elephantine, who is labeled “the child born in Elephantine” in Papyrus Dodgson. However, in the latter case, it is not exactly clear whether this really indicates death as a child or just local derivation.

“At any rate, deified humans were often provided with divine parents. For example, Imhotep and his sister Renpetneferet were regarded as children of Ptah; Amenhotep I was a son of Amun and Mut, Amaunet, or his earthly, but similarly deified mother Ahmose-Nefertari, respectively; Nespameti was considered a son of Khnum and Satet. In that respect, even an adult like Amenhotep I could be represented as a small child in relation to his divine parents.”

Attendant Divinities in Ancient Egypt

On domestic attendant divinities,Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “There arose, from at least the Middle Kingdom, a set of attendant divinities who specialized in the concerns of everyday life: Bes, Taweret, Hathor in her role especially as fertility goddess, and a range of minor protective spirits, as found on the “magic” wands and rods. Though sometimes regarded as peripheral and “popular,” these deities and demons were worshiped and supplicated by individuals of all social classes over most periods of Egyptian history. The Bes images and Taweret figures that appear within New Kingdom palace decoration probably reflect the participation of royalty. The spread of material relating to domestic deities across houses of varying sizes at el-Amarna supports its use across a broad range of socio-economic spectra. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Local divinities were also worshiped in and around the house. Deir el-Medina, in particular, offers abundant evidence of this. The cobra goddess Meretseger was especially popular here, worshiped not only in houses but also in nearby chapels, some on and around the mountain overlooking the Valley of the Kings. Also attested in Deir el-Medina households are Hathor, Ptah, Amun, and Anukis, and local ancestors. In the Ramesside Period, personal experiences of deities, in addition to their supplication in problem-solving, seem to have found prominent expression here in household settings. It is tempting to read the occasional appearance of divinities such as Amun and Ptah within the slightly earlier New Kingdom assemblage at el-Amarna, and the apparent absence of similar figures among Middle Kingdom settlement material, as stages in the gradual growth of personal relationships with state and local deities. It may be, of course, that in these periods expressions of such relationships were embedded in words and actions that only found articulation—material or written—later in history.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024