Home | Category: Religion and Gods

FOREIGN DEITIES IN EGYPT

Egyptian seal impression with the Persian winged god Ahuramadza

Christiane Zivie-Coche of the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes in Paris wrote: “The presence of foreign deities in the Egyptian pantheon must be studied in the light of the openness of Egyptian polytheism and as a reflection on cultural identity. Even if Egyptian self-identity was defined as intrinsically opposed to the Other, i.e. the foreigner, Egypt always maintained contact with its neighbors, particularly Nubia and the Near East. These intercultural contacts had an effect on the religion. Since the earliest times, deities like Dedoun, Ha, or Sopdu formed an integral part of the Egyptian pantheon, so much so that their likely foreign origin is not immediately perceptible. Particularly important is the introduction of a series of Near Eastern deities into the established pantheon at the beginning of the New Kingdom, under the reign of Amenhotep II. Receiving cult from both the state and private individuals, these deities were worshiped under their foreign name while depicted in Egyptian fashion. Their principal function was providing protection. It is the very nature of Egyptian polytheism that allowed for foreign divinities to acquire the same status as the indigenous gods. [Source: Christiane Zivie-Coche, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Paris, translated from French by Jacco Dieleman, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“One could qualify a deity as foreign to the Egyptian pantheon when it has a well-established, non-native origin and is known to have been introduced into Egypt at a specific point in time. Deities that were always associated with Egypt’s frontier zones and formed part of the Egyptian pantheon since the earliest times are not considered foreign. Such deities are the Nubian Dedoun attested since the Pyramid Texts; Ha, god of the West, who is likely Libyan in origin; and also Sopdu, Lord of the East and the eastern borders, whose symbol spd, which serves to write his name in hieroglyphs, bears a resemblance to the Near Eastern betyles or sacred stones. There were also deities of truly Egyptian origin that held power over these marginal regions. Min of Coptos was the Lord of the Eastern Desert and Hathor, besides being a goddess of love and sexual desire, was very much an itinerant deity, honored at the mining sites in the Sinai and Byblos in the Lebanon. This state of affairs reveals, even without considering the principles of interculturality, that Egypt was not the self-contained and closed-off country some scholars make it to be.

“The border crosser par excellence was Seth, who embodies this role in all his ambiguity, being the protector of the sun god in the solar bark, the murderer of his brother Osiris, and the god of the deserts, disturbing and threatening—a trickster. His Otherness led to assimilation with the Near Eastern deity Ba’al in the New Kingdom. At the end of the Third Intermediate Period or the beginning of the Late Period, his “demonization” led to almost complete exclusion from the Egyptian pantheon, when he was regarded solely in his role as fearful enemy of Osiris, and even more so of Egypt as a unified state and society through his identification with foreigners in general. The dangerous Other was thus not necessarily located outside the group of Egypt’s familiar deities, but could be found in their very midst.

“Contacts with foreign cultures, however well established, did not necessarily lead to the introduction of foreign deities on Egyptian soil. The most striking example is that of the Libyan immigration, which eventually brought the 22nd and 23rd Dynasties to power. These kings were descendants of families coming from the west, and later the “great chiefs” of the Ma or the Libou, who governed principalities of different size after the disintegration of Pharaonic rule in the first quarter of the first millennium B.C.. Even if contemporary proper names attest to the popularity of theophoric names composed with, for example, the name of the Libyan goddess Shehededet, no trace of a cult for this deity has been recovered. In fact, the Libyans seem to have had no influence on Egyptian religious practices; on the contrary, they adopted them. The same applies to the Kushite Dynasty and the Persian invaders. They both showed great piety toward the Egyptian deities, with the exception of the Second Persian Domination (343 - 332 B.C.), and did not “import” their own gods. The Ptolemaic and Roman Periods witnessed the creation of a deity of Egyptian origin represented in Greek style, Serapis, a combination of Osiris with Apis. Traditional Egyptian deities could thus undergo the effects of acculturation under the influence of foreign domination, in particular on the level of iconography. Other examples are Harpocrates (Horus the Child) and Isis, who, as terracotta figurines, are always represented in Greek style.

“The deities that can truly be considered foreign in the Egyptian pantheon are primarily deities of Near Eastern, west-Semitic origin, most notably Reshep, Hauron, Ba’al, Astarte, Anat, Qadesh, and a few others. They were introduced in the New Kingdom, more precisely in the reign of Amenhotep II, with the exception of Anat who did not appear, according to the documents at our disposal, before the reign of Ramesses II. Despite historical changes, they remained in the Egyptian pantheon up into the Roman Period.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN GODS AND GODDESSES: TYPES, ROLES, BEHAVIOR AND LETTERS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

FORMS AND EPITHETS OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN GODS AND GODDESSES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

LIST OF EGYPTIAN GODS AND GODDESSES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN CREATION GODS AND MYTHS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CREATION OF MANKIND AND THE MYTH OF THE HEAVENLY COW africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CHILD DEITIES AND DEIFIED HUMANS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

DEMONS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: HISTORY, TYPES, ROLES africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Syro-Palestinian Deities in New Kingdom Egypt: The Hermeneutics of Their Existence” by Keiko Tazawa (2009) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Foreign And Animal Gods” by Lewis Spence (2010) Amazon.com;

“Gods and Men in Egypt: 3000 BCE to 395 CE” by F. Dunand, C. Zivie-Coche and translated by David Lorton (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt” by Richard H. Wilkinson (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses” by George L. Hart (1986) Amazon.com;

“Gods and Myths of Ancient Egypt” by Robert A. Armour Amazon.com;

“The Complete Encyclopedia of Egyptian Deities: Gods, Goddesses, and Spirits of Ancient Egypt and Nubia” by Tamara Siuda (2024) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life of the Egyptian Gods” by Dimitri Meeks (1993) Amazon.com;

“The Gods of Egypt” by Claude Traunecker (1992) Amazon.com;

“The Gods of the Egyptians, Volume 1" by E. A. Wallis Budge (1969) Amazon.com;

“The Gods of the Egyptians, Volume 2" by E. A. Wallis Budge (1969) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt”

by Geraldine Pinch (2004) Amazon.com;

“Uncovering Egyptian Mythology: A Beginner's Guide Into the World of Egyptian Gods, Goddesses, Historic Mortals and Ancient Monsters” by Lucas Russo (2022) Amazon.com;

”Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Emily Teeter (2011) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Rites, Rituals and Religion of Ancient Egypt” by Lucia Gahlin (2001) Amazon.com;

“Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt” by Rosalie David (2003) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Ancient Egypt: Gods, Myths,and Personal Practice” by John Baines (1991) Amazon.com;

Historical and Cultural Context of Foreign Deities in Egypt

Christiane Zivie-Coche of the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes wrote: “During the periods preceding the New Kingdom, interaction with people from the Near East was mainly with those who had settled more or less permanently in Egypt, primarily in the north of the country. The most significant episode was that of the Hyksos, “rulers of foreign lands,” who, for about one century, ruled in the Delta with Avaris (Tell el-Dabaa) as their capital. Excavations at the site have revealed obvious Near Eastern cultural influences, particularly in the funerary domain. As regards cult, however, there is no evidence to affirm, as certain scholars do, that the Near Eastern Ba’al or Anat received cult there. The epigraphic documents, few in number, mention Seth but never Ba’al, whereas Anat occurs only once as a component in a theophoric name . One can only conclude that Seth was the principle deity, if not the sole one, adopted by the Hyksos. [Source: Christiane Zivie-Coche, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Paris, translated from French by Jacco Dieleman, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“After the reconquest of the territory and the installation of the 18th Dynasty, Egypt rapidly opened up to the Near East, the Mediterranean coast, Ugarit, and Mitanni; this was at first achieved primarily through military conquest and subsequent subjugation of the Near East to Egypt, but eventually also through marriage alliances with the Mitanni and the Hittites, as well as economic and linguistic exchange. As much as the Egyptians erected cult places for their own deities in the foreign cities they dominated, most likely to serve soldiers stationed in these posts or functionaries on mission, they also brought back deities encountered abroad. These new cults installed at several locations in Egypt have often been taken as initiatives of foreigners—prisoners of war serving in the estates of temple or king, who continued their own cults.

“The available documentation indicates otherwise. The first mentions of Reshep, Hauron, and Astarte occur in royal documents dating to the beginning of the reign of Amenhotep II (1425 - 1399 B.C.): the Victory Stela of Memphis, a rock stela of year 4 in a quarry at Tura, the Sphinx Stela at Giza from the beginning of his reign, foundation plaques of the chapel of Harmachis at Giza, and the so-called Astarte Papyrus mentioning his regnal year 5. As for Qadesh, the earliest attestation dates to the reign of Amenhotep III (1389 - 1349 B.C.) occurring on a statue of Ptahankh, an associate of the high priesthood of Ptah. All these documents share another particularity: they come from Memphis and make frequent allusions to Peru-nefer, the port of Memphis with an important military and economic function. Peru-nefer had a pantheon that was quite unique, comprising the majority of known foreign gods under the aegis of Amun “Lord of Peru-nefer,” whose membership has recently been established. Far from signaling the presence of foreigners, these documents translate an all too clear willingness, political and religious, on the part of the state to put new cults in place. If this were not the case, how can the presence of foreign deities on royal monuments be explained? The same maneuver can be seen in the 19th Dynasty, when Ramesses II (1290 - 1224 B.C.) declares himself protected and beloved by the goddess Anat and lets himself be represented at her side in two monumental dyads, or even figures as a child underneath the throat of the Hauron-falcon—all statues erected at Pi-Ramesses. The same pharaoh erected a stela commemorating the 400th year of rule of Seth depicted as Ba’al. Once officially adopted, these deities became widespread in Egypt, occasionally as far south as Nubia.”

“Deities of the ancient Near East were thus introduced through official channels into the Egyptian pantheon from the 18th Dynasty onwards, which is not so surprising given the close relations between centralized government and religion in ancient Egypt. The question remains, though, if there is a clear answer to why these deities were adopted, enabling them eventually to play a role in all domains of Egyptian religion. Theologically, nothing prevented the presence of foreign deities in the Egyptian pantheon. After a period of occupation followed by reconquest of its territory, Egypt affirmed its supremacy over its neighbors, while appropriating some of their practices and technical innovations, thus showing a certain degree of permeability to other cultures. In this process, foreign deities, at least some of them, were able to be “imported” into Egypt’s imaginary world. They represented an additional, new, and beneficial force, which could be claimed by the king and, following his example, by priests and private individuals alike, either in an official setting or as refuge in private life. The validity of Egyptian religion was neither measured by the rejection of deities of other peoples nor by the denial of their existence and veracity. On the contrary, the principle of polytheism allowed for integrating new deities without challenging its conception of the world of the divine, but instead enriching and diversifying it.”

Polytheism, Otherness and Foreign Deities in Egypt

Nubian statue

Christiane Zivie-Coche wrote: “Like so many other traditional societies, Egypt defined itself ethnocentrically as the center and origin of civilization. Egyptians are “humans” (rmT), whereas foreigners are called by their ethnic name. The foreigner is the Other; a being that does not speak Egyptian and is a source of danger and disorder. This explains the innumerable representations, from the Old Kingdom up into the Roman Period, that depict the king holding several foreign enemies by their hair, ready to sever their heads. If only symbolic in meaning, this violent image lays bare how the Other is viewed in Pharaonic ideology. The cosmic, political, and social order, embodied in Maat and upheld by the king, is perpetually menaced by the Other. This Other can be an earthly enemy, like a foreigner, but also a divine enemy, like Apep, the snake that each day threatens the journey of the bark of Ra along the sky and through the duat. This fragile equilibrium can only be maintained by the daily performance of rituals. [Source: Christiane Zivie-Coche, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Paris, translated from French by Jacco Dieleman, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“In contrast with this ideology, there was a practical reality, which, since the earliest times, encouraged Egyptians to interact with foreigners, and not only in a military context, to learn foreign languages and to use translators, and to increase foreign trade. This opening up to the world eventually led to changes in religious beliefs. Hymns written during the New Kingdom evoke the demiurge as creator of all peoples, distinguished by the color of their skin and speaking in different tongues since the time of creation (Great Aten Hymn). The cosmographic books, found in the royal tombs of the New Kingdom, depict the four races—Egyptian, Nubian, Libyan, and Asiatic—as participating in the afterlife in the Egyptian duat (Book of Gates, 5th hour). The demiurge is now recognized, in a non-theoretical way, as the creator of all humanity.

“What is the status of foreign deities in such a worldview? The existence of foreign gods or the gods of foreigners, despite evident ethnocentric tendencies, could easily be accepted into the framework and worldview of Egyptian religion, because it is polytheistic. Egyptian polytheism accepts every other deity, every new deity, as such, based as it is on the principle of plurality of divine beings, forms, and names. Not based on the principles of truth and exclusion, the existence of no deity can be refuted on the ground of falsity. This is not a matter of what one calls today religious tolerance, but a fundamentally different concept of the divine, which allows for the addition, if the need is felt, of a new deity in a long-established pantheon—irrespective of the deity’s origin, as it is of the same nature as those deities with which it will be integrated.”

Names and Epithets of Foreign Deities in Egypt

Christiane Zivie-Coche wrote: “When introduced into the Egyptian world of the divine, foreign deities were qualified as netjer, “god,” like indigenous deities. In every case, their original name was preserved, transcribed into Egyptian hieroglyphic or hieratic with so-called syllabic-writing, a common method to transcribe words of Semitic origin into Egyptian. One can therefore not speak of an interpretatio aegyptiaca: foreign deities were not simply equated with Egyptian deities of a similar nature, but fully adopted into the pantheon. There are, however, some particular cases. Hauron was so closely associated with Harmachis, name of the Great Sphinx of Giza in the New Kingdom, that one addressed him indifferently as Harmachis, Hauron, or Hauron-Harmachis. [Source: Christiane Zivie-Coche, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Paris, translated from French by Jacco Dieleman, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“As regards Ba’al, his name is often written with the Seth-animal as its determinative, a sign that could also serve as an ideogram for writing the name of Seth. One could consider reading the name as Ba’al-Seth; whatever the case, it reveals that Egyptians felt a close association between the two deities. Moreover, in documents of the Ramesside Period there is an image of an easternized god with exotic clothing that is always accompanied by the name of Seth. Two aspects are combined here: a Seth-Ba’al, an Egyptian deity made eastern to convey Egyptian power across the borders, and a Ba’al-Seth, an eastern deity installed at Memphis and later elsewhere in Egypt. The goddess Qadesh, who is not a simple hypostasis of Astarte and Anat, represents a unique case, because her name is an Egyptian invention. Using the Semitic root q-d-š, Egyptians created the theonym, “the Blessed,” which was otherwise unknown in the ancient Near East.

“The epithets associated with these deities only rarely give information about the deity’s geographical origin. For example, an epithet on a sphinx statuette indicates that Hauron is originally from Lebanon, and a private stela records that Astarte is from Kharou. Their origin was neither forgotten nor unknown but held little importance in the new Egyptian setting. Most epithets are rather commonplace, expressing the power of the divinity (“great god”) and its celestial role (“lord/lady of the sky”); goddesses were often called “Mistress of the Gods” or “Mistress of the Two Lands.” Occasionally, family ties are specified: Astarte is the daughter of Ptah of Memphis, or of Ra, as is Anat. These two goddesses are frequently associated, without their sisterhood being clearly stated. They may also play a role in an Egyptian myth. For example, in the Harris Magical Papyrus, Anat and Astarte appear to be pregnant by Seth, but are unable to deliver the baby.”

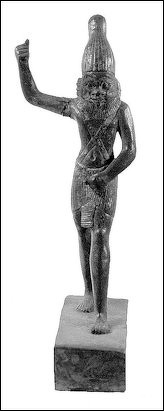

Images of Foreign Deities in Egypt

Egyptain god Min with a Bes-like face standing in a position like the Middle Eastern god Baal

Christiane Zivie-Coche wrote: “Upon their adoption into Egypt, a visual image had to be developed for the newcomers, whose iconography was neither well established nor often represented in their region of origin. The preserved documents, statues, stelae, and temple reliefs show that their visual form followed the Egyptian model and its stringent rules of representation. Foreign deities can be recognized by attributes, which serve less to mark their “foreignness” than their function and character. Thus, Reshep, who may be dressed with an Egyptian loincloth or a Syrian kilt with shoulder strap, is shown with an Egyptian divine beard or with the Asiatic pointed goatee while wearing a crown similar to the Egyptian white crown. The crown is often adorned with two floating ribbons and a gazelle head in place of a uraeus. This symbol is by no means characteristic of the Asiatic god: Shed, the child archer god, is equipped with it likewise. Reshep is generally represented with shield, quiver, and arrows, which do not mark him as a god of war but a god ensuring protection of those who invoke him. [Source: Christiane Zivie-Coche, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Paris, translated from French by Jacco Dieleman, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“The image of Ba’al or rather of Seth-Ba’al is not very different, except that he is unarmed and wears a slightly different crown. Hauron is the only foreign deity to have adopted a mixed form of half animal, half human body. He is represented as a sphinx or a human with falcon head, which both are Egyptian forms of old and closely associated with the deity Harmachis. Astarte, mistress of horses, is represented as a young woman, sometimes androgynous, on horseback. Qadesh is recognizable by the fact that she is represented frontally, generally nude, while standing on a lion, holding serpents and a bouquet of papyrus in her hands and donned with a Hathor wig that is occasionally surmounted by different crowns.

“Frontal representation and nudity are rare in Egyptian iconography, though not unique to Qadesh; they can also be observed in child deities, such as Horus on the Crocodiles, and Bes, the deformed dwarf with prophylactic power. In conclusion, the attributes serve to identify the deities in the same way as indigenous gods without marking them as foreign per se. Once created in Egypt, this imagery exerted in return a strong influence on the iconography of the Near East in the second millennium B.C., which was largely Egyptianized. The iconographic motifs found at Ugarit, on Cyprus, and later in Phoenicia testify to the impact of Egyptian culture in these regions.”

Foreign Deity Cults in Egypt

Christiane Zivie-Coche wrote: “The cult rendered to these deities, once integrated in Egypt, appears to have been Egyptian in form, with Egyptians as devotees and cult specialists. It cannot be excluded that immigrants from the Near East rendered cult to them as well. However, neither proper names nor professional titles in private documents allow the conclusion, as has often been stated, that these cults testify to the presence of foreign communities that maintained their deities and customs. For example, in the Memphite region and in Deir el-Medina, where several foreign deities were worshipped, the devotees were fully integrated into Egyptian society. [Source: Christiane Zivie-Coche, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Paris, translated from French by Jacco Dieleman, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“It is true that no major temples were ever dedicated to these deities, as their significance was never big enough, but in this respect they resemble indigenous deities of limited local importance. Being protectors of the king, private individuals turned to them for help and protection, in conformity with the principles of personal piety, a religious phenomenon that became prevalent in the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.). The scribes of the Houses of Life, who composed formularies like the Magical Papyrus Harris, Papyrus Chester Beatty VII, and Papyrus Leiden I 348, often invoked foreign deities as an efficacious cure against scorpion stings, serpent bites, and various diseases and illnesses, in the same way they invoked Seth, Isis, or others. In other words, these deities had acquired an identity proper to Egypt, which only partially depended upon their original characteristics.”

Herodotus on Egyptian and Greek Gods

Isis temple in Delos, Greece

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “In fact, the names of nearly all the gods came to Hellas from Egypt. For I am convinced by inquiry that they have come from foreign parts, and I believe that they came chiefly from Egypt. Except the names of Poseidon and the Dioscuri, as I have already said, and Hera, and Hestia, and Themis, and the Graces, and the Nereids, the names of all the gods have always existed in Egypt. I only say what the Egyptians themselves say. The gods whose names they say they do not know were, as I think, named by the Pelasgians, except Poseidon, the knowledge of whom they learned from the Libyans. Alone of all nations the Libyans have had among them the name of Poseidon from the beginning, and they have always honored this god. The Egyptians, however, are not accustomed to pay any honors to heroes. 51. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2 English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“These customs, then, and others besides, which I shall indicate, were taken by the Greeks from the Egyptians. It was not so with the ithyphallic images of Hermes; the production of these came from the Pelasgians, from whom the Athenians were the first Greeks to take it, and then handed it on to others. For the Athenians were then already counted as Greeks when the Pelasgians came to live in the land with them and thereby began to be considered as Greeks. Whoever has been initiated into the rites of the Cabeiri, which the Samothracians learned from the Pelasgians and now practice, understands what my meaning is. Samothrace was formerly inhabited by those Pelasgians who came to live among the Athenians, and it is from them that the Samothracians take their rites. The Athenians, then, were the first Greeks to make ithyphallic images of Hermes, and they did this because the Pelasgians taught them. The Pelasgians told a certain sacred tale about this, which is set forth in the Samothracian mysteries. 52.

“Among the Greeks, Heracles, Dionysus, and Pan are held to be the youngest of the gods. But in Egypt, Pan [Egyptian Khem] is the most ancient of these and is one of the eight gods who are said to be the earliest of all; Heracles belongs to the second dynasty (that of the so-called twelve gods); and Dionysus to the third, which came after the twelve. How many years there were between Heracles and the reign of Amasis, I have already shown; Pan is said to be earlier still; the years between Dionysus and Amasis are the fewest, and they are reckoned by the Egyptians at fifteen thousand. The Egyptians claim to be sure of all this, since they have reckoned the years and chronicled them in writing. Now the Dionysus who was called the son of Semele, daughter of Cadmus, was about sixteen hundred years before my time, and Heracles son of Alcmene about nine hundred years; and Pan the son of Penelope (for according to the Greeks Penelope and Hermes were the parents of Pan) was about eight hundred years before me, and thus of a later date than the Trojan war. 146.

“With regard to these two, Pan and Dionysus, one may follow whatever story one thinks most credible; but I give my own opinion concerning them here. Had Dionysus son of Semele and Pan son of Penelope appeared in Hellas and lived there to old age, like Heracles the son of Amphitryon, it might have been said that they too (like Heracles) were but men, named after the older Pan and Dionysus, the gods of antiquity; but as it is, the Greek story has it that no sooner was Dionysus born than Zeus sewed him up in his thigh and carried him away to Nysa in Ethiopia beyond Egypt; and as for Pan, the Greeks do not know what became of him after his birth. It is therefore plain to me that the Greeks learned the names of these two gods later than the names of all the others, and trace the birth of both to the time when they gained the knowledge. 147.”

Herodotus on Heracles in Ancient Egypt

Textile with Hercules from AD 4th century Egypt

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “Concerning Heracles, I heard it said that he was one of the twelve gods. But nowhere in Egypt could I hear anything about the other Heracles, whom the Greeks know. I have indeed a lot of other evidence that the name of Heracles did not come from Hellas to Egypt, but from Egypt to Hellas (and in Hellas to those Greeks who gave the name Heracles to the son of Amphitryon), besides this: that Amphitryon and Alcmene, the parents of this Heracles, were both Egyptian by descent26 ; and that the Egyptians deny knowing the names Poseidon and the Dioscuri, nor are these gods reckoned among the gods of Egypt. Yet if they got the name of any deity from the Greeks, of these not least but in particular would they preserve a recollection, if indeed they were already making sea voyages and some Greeks, too, were seafaring men, as I expect and judge; so that the names of these gods would have been even better known to the Egyptians than the name of Heracles. But Heracles is a very ancient god in Egypt; as the Egyptians themselves say, the change of the eight gods to the twelve, one of whom they acknowledge Heracles to be, was made seventeen thousand years before the reign of Amasis. 44.[Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“Moreover, wishing to get clear information about this matter where it was possible so to do, I took ship for Tyre in Phoenicia, where I had learned by inquiry that there was a holy temple of Heracles.27 There I saw it, richly equipped with many other offerings, besides two pillars, one of refined gold, one of emerald: a great pillar that shone at night; and in conversation with the priests, I asked how long it was since their temple was built. I found that their account did not tally with the belief of the Greeks, either; for they said that the temple of the god was founded when Tyre first became a city, and that was two thousand three hundred years ago. At Tyre I saw yet another temple of the so-called Thasian Heracles. Then I went to Thasos, too, where I found a temple of Heracles built by the Phoenicians, who made a settlement there when they voyaged in search of Europe; now they did so as much as five generations before the birth of Heracles the son of Amphitryon in Hellas. Therefore, what I have discovered by inquiry plainly shows that Heracles is an ancient god. And furthermore, those Greeks, I think, are most in the right, who have established and practise two worships of Heracles, sacrificing to one Heracles as to an immortal, and calling him the Olympian, but to the other bringing offerings as to a dead hero. 45.

“And the Greeks say many other ill-considered things, too; among them, this is a silly story which they tell about Heracles: that when he came to Egypt, the Egyptians crowned him and led him out in a procession to sacrifice him to Zeus; and for a while (they say) he followed quietly, but when they started in on him at the altar, he resisted and killed them all. Now it seems to me that by this story the Greeks show themselves altogether ignorant of the character and customs of the Egyptians;for how should they sacrifice men when they are forbidden to sacrifice even beasts, except swine and bulls and bull-calves, if they are unblemished, and geese? And furthermore, as Heracles was alone, and, still, only a man, as they say, how is it natural that he should kill many myriads? In talking so much about this, may I keep the goodwill of gods and heroes! 46.”

Temple Dedicated to Zeus-Kasios

In March 2022, archaeologists in Egypt announced that had found the remains of an ancient temple built to honor Zeus-Kasios, a deity merging characteristic of the Greek gods Zeus and the weather-god Kasios, the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities said. [Source Laura Geggel, Live Science, April 27, 2022]

Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science: The ruins were unearthed at the Tell el-Farama archaeological site on the northwestern Sinai Peninsula. In Greco-Roman times (332 B.C. to A.D. 395), this area was known as the city and harbor of Pelusium, which sat on the far eastern mouth of the Nile River. Due to its strategic location, people used Pelusium for various functions, including as a fortress during the time of the Egyptian pharaohs; and artifacts dating to the Graeco-Roman, Byzantine, Christian and Islamic periods suggest it was in use in various ways then as well, according to a 2010 paper presented at a the Sinai International Conference for Geology and Development.

The archaeological team zeroed in on the temple after excavating around the remains of two pink granite columns lying on the ground's surface, Mostafa Waziri, secretary-general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities, said in the statement. These columns once formed the temple's front gate, but collapsed in ancient times when a mighty earthquake rocked the city.

Researchers have been aware for several decades that there might be a Zeus-Kasios temple at the site. In the early 1900s and later in the 1990s, archaeologists ascertained that the granite columns were likely brought on barges via the Nile from Aswan in southern Egypt to Pelusium, according to the 2010 paper. Moreover, the late French Egyptologist Jean Clédat found Greek inscriptions at the site, indicating that a temple for Zeus-Kasios had been built there in Graeco-Roman times. However, archaeologists never did a formal excavation at the site, which is near an ancient fort and a church.

Now, archaeologists have discovered previously unknown remains of the temple, including granite blocks that were likely part of a staircase leading to the temple's entrance on the eastern side of the building, Ayman Ashmawy, head of the Egyptian Antiquities sector at the Supreme Council of Antiquities, said in the statement.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024