Home | Category: Religion and Gods

THOTH

Thoth

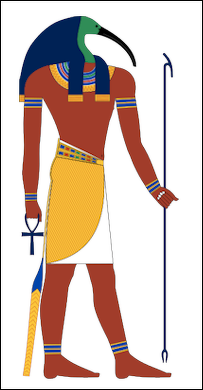

Ibis-headed Thoth was best known as a god of writing and wisdom but was also the god of knowledge, learning, measurement, historical records, science, magic and scribes. Regarded as a cosmic deity, creator god, and warrior, he had a good memory and was involved in the after-life ceremony of the dead in which the heart was weighed against the feather of truth. Thoth was the lord of the moon and was sometimes represented as a baboon. Temples devoted to Thoth were often filled with caged ibises and other birds that were mummified after death. Seshat, the goddess of writing and the divine keeper of royal annals, was represented as a woman.

Thoth was a lunar deity and vizier of the gods. Both the ibis and the ape were sacred to him. Thoth was associated with Hermopolis in Middle Egypt, the home of his main temple, and was considered the inventor of writing. During the judgment of the dead he was the scribe who recorded the confessions and affirmations of the dead on his scrolls, and also kept a record of who went into paradise and who was eaten by the dogs of judgment. He is often seen recording the deeds of the dead at the day of their judgment in the Book of the Dead.. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

Barbara Waterson wrote for the BBC: Thoth “acted as scribe to the gods, his chief activities being to record the verdict on the dead who were tried in the Hall of Judgement; and to inscribe on the sacred mimusops (persea-tree) the number of years a king had allotted to him for his reign. Thoth was believed to have a book containing all the wisdom of the world within it. His chief place of worship was Hermopolis Magna (the modern el-Ashmunein), so called by the Greeks who equated him with Hermes, their messenger of the gods.” [Source: Barbara Waterson, BBC, March 29, 2011]

Mark Millmore wrote in discoveringegypt.com: Thoth was usually depicted as a man with the head of an ibis holding a scribe’s pen and palette, or as a baboon. The Greeks ascribed to him the invention of all the sciences as well as the invention of writing. He is often portrayed writing or making calculations. Thoth was as old as the oldest gods and often acted as an intermediately between gods. He was sometimes shown wearing a moon disk and crescent headdress. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Martin A Stadler of the University of Wuerzburg wrote: “Being one of the oldest deities of the Egyptian pantheon, he is attested in many sources from the earliest periods of Egyptian history up to the Roman Period. The etymology of his name remains unexplained, possibly due to the name’s antiquity. Perhaps it is his age as a divine figure that led to a rather confusing mythology with a series of contradicting traditions concerning his descent and his reputation as a benevolent versus atrocious or mistrusted deity. Under the influence of Hellenism, he transformed into Hermes Trismegistos in Roman times and lived on as such well into the European renaissance. [Source: Martin A Stadler , University o Wuerzburg, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“The ancient Egyptian god Thoth is usually termed “god of wisdom,” “scribal god” or “divine scribe,”as well as “lunar deity” or “divine vizier.” These functions set Thoth apart from most other gods and thus may be regarded as typical for him, but at the same time they are reductionist. Thoth is attested from the earliest historical periods onwards: he already plays a prominent role in the oldest religious texts of Egypt, the Pyramid Texts, and continues to appear almost everywhere in Egypt up to the end of Egyptian religion some 4000 years later, transforming into the Hermes Trismegistos of late antiquity, and living on as such well into the European renaissance. Throughout this long period the god is overwhelmingly present in a vast body of documentation that yields an extraordinarily colorful picture of the god’s nature and functions within the Egyptian pantheon. The more data and sources are collected the more Thoth’s picture becomes blurred and it seems that he embodies almost every possible aspect one could imagine a god to have within Egyptian mythology: in addition to the characterizations mentioned above, he is found acting as a cosmic deity, a primeval creator, and a warlike divinity. From this it may be concluded that Thoth may be one of the oldest deities within the Egyptian pantheon, which may be one of the reasons why his Egyptian name, 9Hwtj, cannot be explained satisfyingly, as the theonym’s etymology may reach back into periods for which no written sources are available.

“Thoth appears virtually everywhere—in the major religious corpora (Pyramid Texts, Coffin Texts, Book of the Dead, and temple inscriptions), literature, and in the visual arts, as pointed out above. One major source not been mentioned so far is a text entitled by the modern editors Book of Thoth, which may be the mysterious and powerful writing often referred to in Egyptian literature. It has survived in numerous manuscripts and is a dialogue between a wisdom-seeking disciple and a master—Thoth according to the editors—and thus it may be a precursor to the Hermetic writings. Quack has disputed such an interpretation and maintained that the text is the ritual for the initiation to the scribal profession and that the disciple speaks with at least four persons, none of whom are Thoth. However, the respondents’ designations can be seen as antonomasias for Thoth. During an initiation rite such as Quack has proposed we can imagine that the participants took on mythic roles, therefore possibly including those of Thoth and a disciple engaged in a dialogue.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

OSIRIS (GOD OF THE DEAD AND THE AFTERLIFE): MYTHS, CULTS, RITUALS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ISIS (EGYPTIAN GODDESS OF MAGIC AND MOTHERLY LOVE): HISTORY, IMAGES, AND SPREAD OF HER CULT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SETH, THE GOD OF CHAOS: HISTORY, MYTHS, CULT CENTERS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

HORUS, THE FALCON-HEADED PATRON OF KINGS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN GODS AND GODDESSES: TYPES, ROLES, BEHAVIOR AND LETTERS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

FORMS AND EPITHETS OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN GODS AND GODDESSES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

LIST OF EGYPTIAN GODS AND GODDESSES africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt” by Richard H. Wilkinson (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses” by George L. Hart (1986) Amazon.com;

“Gods and Myths of Ancient Egypt” by Robert A. Armour Amazon.com;

“Gods and Men in Egypt: 3000 BCE to 395 CE” by F. Dunand, C. Zivie-Coche and translated by David Lorton (2005) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Encyclopedia of Egyptian Deities: Gods, Goddesses, and Spirits of Ancient Egypt and Nubia” by Tamara Siuda (2024) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life of the Egyptian Gods” by Dimitri Meeks (1993) Amazon.com;

“The Gods of Egypt” by Claude Traunecker (1992) Amazon.com;

“The Gods of the Egyptians, Volume 1" by E. A. Wallis Budge (1969) Amazon.com;

“The Gods of the Egyptians, Volume 2" by E. A. Wallis Budge (1969) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt”

by Geraldine Pinch (2004) Amazon.com;

“Uncovering Egyptian Mythology: A Beginner's Guide Into the World of Egyptian Gods, Goddesses, Historic Mortals and Ancient Monsters” by Lucas Russo (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Penguin Book of Myths and Legends of Ancient Egypt” by Joyce Tyldesley (2010) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Mythology: A Traveler's Guide from Aswan to Alexandria” by Garry J. Shaw (2021) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Mythology: An Enthralling Overview of Egyptian Myths, Gods, and Goddesses” by Enthralling History (2022) Amazon.com;

”Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt” by Emily Teeter (2011) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Rites, Rituals and Religion of Ancient Egypt” by Lucia Gahlin (2001) Amazon.com;

“Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt” by Rosalie David (2003) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Ancient Egypt: Gods, Myths,and Personal Practice” by John Baines (1991) Amazon.com;

Images of Thoth

Martin A Stadler of the University of Wuerzburg wrote: “Thoth’s manifestations are of two main types: as an ibis or ibis-headed man, and as a baboon. On Pre- and Early Dynastic palettes the king is accompanied by a series of standards. Often on one of them stands an ibis designated as the Lord of Hermopolis, i.e., Thoth, in his later, canonized form. The typical writing of “Thoth” in the Pyramid Texts is the ibis on a standard ), which suggests that the ibis is already the deity’s normal iconography as early as the Old Kingdom. Therefore these early depictions could also be interpreted as attestations of Thoth. For example, a rock relief from the Sinai, carved during one of the mining expeditions of Khufu’s reign, shows the king smiting an enemy in front of an ibis- headed god. This would be the oldest known depiction of Thoth in ibis-headed form. However, there is no caption specifying identity, which leaves some uncertainty, because in Egypt a deity can take different shapes, or a certain shape can be taken by different deities. Accordingly, in most cases the ibis does denote Thoth, but very rare exceptions do occur. It is hard to say whether the ibis- iconography of deities other than Thoth always aims at assimilating the depicted god to Thoth—for example, the souls (bAw) of Hermopolis are shown as ibis-headed figures. That is certainly not a coincidence, Hermopolis being Thoth’s chief cult-center. Therefore, it may be speculated whether the representation of an ibis-headed goddess should be associated with Thoth, but this remains a hypothesis for which only circumstantial evidence can be adduced. [Source: Martin A Stadler , University o Wuerzburg, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

Thoth

Usually the squatting baboon, its hands on its knees, is to be identified as a theriomorphic transformation of Thoth, sometimes with the lunar disc and crescent on its head. The statue of a baboon in the cult chamber of the baboons at Tuna el-Gebel, the Late to Roman Period necropolis of Thoth’s cult-center in Upper Egypt, shows this iconography. On votive stelae, inscriptions identify the squatting baboon, its hands on its knees, as “Lord of Hermopolis”. Conversely, the baboon is quite often found not to represent Thoth. For instance, baboons adoring the rising sun may be an early manifestation of the Hermopolito- Theban ogdoad. Furthermore, one of Horus’s sons, Hapi, is shown as a man with an ape-head, which is not easily distingushed from a baboon’s head. The depiction of a striding, baboon-headed man in a ritual scene from Tuna el-Gebel does not show Thoth, either, in much the same manner as an ibis- headed mummy represents the deceased sacred ibis.

“Both the ibis-headed man and the baboon are associated with Thoth’s scribal role, whether it be that he records the results of the judgment after death, assigns a long reign to the king, inscribes the king’s name on the ished-tree), or that scribes represent themselves as being under the protection of the deity in the form of a baboon. Whereas Thoth as an ibis- headed man is quite standard, the ape-headed man who presumably stands for Thoth is rather exceptional, as in the judgment scene on the Theban coffin lid BM EA 6705.

“Besides the ibis and the baboon, Thoth can manifest himself in three other forms (excluding derivatives of the aforementioned baboon- and ibis-iconographies, such as an ibis-headed lion). A particular cult image of Thoth, which Thutmose III donated to the temple of Osiris at Abydos, and which bears the epithet sxm nTrw, “power of the gods,” is uniquely worshipped in the guise of a sxm-scepter. There are, additionally, some indicators suggesting that the falcon can also represent the god. Although the falcon tends to be a rather generic symbol for the divine in general, it might also express overlappings with Horus. Finally, Thoth is rarely depicted purely anthropomorphically. One such example is found at Hermopolis from the reign of Sety II . There Thoth is shown, wearing the lunar disc and crescent, on the doorway of the Amun-temple’s pylon. Since the relevant caption calls him “of Ramesses, beloved of Amun”, it has been assumed that this is a personality distinct from the standard Thoth.

“However, a series of anthropomorphic depictions such as that at Karnak suggests that all such representations should be identified as Thoth himself rather than postulating different manifestations of Thoth. Perhaps they serve to emphasize Thoth’s lunar aspect, because both the lunar deity Khons and Iah-Thoth (Moon-Thoth) can also appear as a man wearing the lunar disc and crescent on his head. Considering Thoth of Pnubs in ritual scenes, either striding or enthroned and usually wearing the four- feathered crown above a wig with short curls, the anthropomorphic iconography might sometimes also refer to Thoth in the Myth of the Solar Eye and his role in bringing back the sun-god’s daughter to Egypt.”

Thoth Mythology

Martin A Stadler of the University of Wuerzburg wrote: “Contrary to Osiris, on whom a biography can be written, despite variant traditions, as though he had been a real human being, Thoth does not allow for the establishment of such a mythological biography, because there are highly contradictory sources pertaining to his coming into being , and none of them can be categorized as primary without reservation. Thoth is termed as having been autogenously born, having no mother, but other sources describe him as a son of goddesses (Nut, Neith, Rat-taui, goddess of Imet, or an unspecific “Great One” [wrt]), or having emerged from the cranium of Seth after Seth had been impregnated with Horus’s semen. The Bubastis tradition has it that Thoth is the child born from Seth’s rape of Horit, who subsequently delivers into the water an egg, later found as a baboon by a black ibis. The tradition thus appears as an attempt to bring together various versions and to explain the two forms of Thoth. When Thoth is engaged in activities concerning Osiris’s corpse, and is involved in the world’s creation. Nonetheless, Thoth can act as a creator god, for which a particular iconography—a naked ibis-headed man whose toes are jackal heads—may have been developed , or he can be perceived as the creator’s intellectual capacity and faculty of speech, through which everything is conceptualized and called into being, qualifying Thoth for his intimate relationship with language and texts. [Source: Martin A Stadler , University o Wuerzburg, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“It seems as though Thoth is a deity without a “childhood,” because there is no tradition for his growing up except for indirect hints that refer to his rejuvenation as a lunar deity, but that Osirian funerary rituals, he appears as Osiris’s son. This, however, should be taken as a functional term of kinship, since it was a son’s duty to bury his father. Indeed Thoth shares such a filiation with Anubis. Thoth hatching from an egg is an occasionally repeated Egyptological conjecture that lacks evidence. It goes back to an unproven connection between the two stones from which Thoth emerges, according to Spell 134 of the Book of the Dead, and the egg shells of the primeval egg, which were kept in Hermopolis as relics. Rejuvenation is, of course, a cyclical and cosmic one. Whenever Thoth appears in action there is no reference made to his being, or having been, a child. He is always presented as an adult. Again contrary to Osiris his relationship to a goddess is not essential to his identity—indeed it is even less so than that of Amun to his consort, Mut, in Thebes or Horus of Edfu to Hathor, although in Hermopolis he is coupled with Nehemetaway. His affiliation with Nehemetaway, however, merely seems to somewhat in competition with Anubis as embalmer—and as an archetypical lector priest . One source implies that, according to a Letopolitan tradition, Thoth was not exactly free of blame in the murder of Osiris, whom he, together with Horus, killed accidently during the primordial battle against the cosmic enemies, Thoth actually completing the murder. Such a violent action is not alien to Thoth, surprising though it may seem for the “god of wisdom.” He predominantly appears as a slaughterer of inimical beings in the older sources and this feature was retained follow a general trend of systematizing the gods in triads and has little if any impact on his mythology. Elsewhere Thoth appears with Seshat, who shares with him the characteristic of scribal competence.

Ibis symbolizing Troth from a coffin

“Thoth’s intervention is a necessary component of all the major Egyptian complexes of myths: in the Osiris-myth he participates in the mummification rites— usually reciting the spells, but also being throughout Egyptian history. It is therefore not surprising that Thoth himself is injured during the struggles of Horus and Seth for the succession of Osiris. In this myth, however, most sources describe him as the judicial expert in the lawsuit between the two contenders. Either he is featured as a judge himself, or his knowledge is requested by other deities who ask for his opinion when having to decide who should succeed Osiris. In some texts Thoth is referred to as “chief judge”. This allows his identification with the vizier in the divine sphere, just as on earth the vizier is the chief judge in Egypt. The association does not exclude describing, or identifying, the king’s actions as those of Thoth even in Ptolemaic and Roman captions , nor is it a late development, because already in the Pyramid Texts the king plays the administrative role of Thoth, is his son, or receives his help. It is in the myth of Horus and Seth as reported in Papyrus Chester Beatty I that Thoth exclusively fulfills scribal duties—his most prominent role from the Middle Kingdom onwards. To conclude from this text that Thoth is a divine but subaltern secretary who receives orders rather than acts through his own power overlooks the weight that the other deities assign to his juristic assessments.

“In the course of the battles of Horus and Seth, Horus’s eye is injured. The injured eye is subsequently healed by Thoth. In many of Thoth’s epithetical captions, this mytheme has been associated with his achievement in the Myth of the Solar Eye. There the sun-god sends him out to retrieve his daughter, who is her father’s eye. Having been insulted, she has left Egypt in a rage for Nubia, and it is Thoth’s duty to appease her and convince her to return to Egypt. The myth can be reconstructed from many allusions in a multitude of temple inscriptions and other religious texts—the Pyramid Texts, the Coffin Texts, and the Book of the Dead, among others—and was widely used as a source of metaphors and epithets in later temple inscriptions , but is narrated in its most comprehensive form in a Demotic papyrus.

“Because the sun-god’s daughter appears in the shape of a lion in the Myth of the Celestial Cow , the Egyptians perceived some connections between the Myth of the Solar Eye and the Myth of the Celestial Cow, particularly concerning the leonine goddess. Thoth’s role in the latter myth, however, is quite different from his role in the former. In the Myth of the Celestial Cow, which is one version of the mytheme of a rebellion against the sun-god some time after the world’s creation, the sun-god retires to the sky and appoints Thoth, being the vizier (TAtj), as his representative (stj Ra)—an appointment endowing Thoth with the power to send (hAb) those who are greater (or older) than he to command the primeval gods and to drive back (anan) foreign peoples (HAw-nbw). Thus the sun-god creates the ibis (hbj) and the baboon (anan) of Thoth by means of a pun. In Spell 175a of the Book of the Dead, a dialogue between the solar creator (here named Atum) and Thoth is preserved and best understood in the context of the Myth of the Celestial Cow. Atum complains about the rebels and asks the advice of Thoth, who promises to solve the problem and introduces mortality to mankind.

“Thus, Thoth is not an unequivocally beneficent god, but also a god who was distrusted at times. Possibly connected with his aforementioned lunar aspect and the phenomenon of the lunar month comprising a little less than 30 days, he can be accused of having stolen from the offerings and of having disturbed the cosmic order. Such an accusation was developed for instance in a “hymn” to Thoth found in papyri Chester Beatty VIII and Greenfield and in the charge raised by Baba against Thoth according to Papyrus Jumilhac. This charge of theft is quite delicate, as he is also responsible for ascribing the offerings to the gods.”

Cult and Worship of Thoth

Martin A Stadler of the University of Wuerzburg wrote: “The competing and contradicting traditions of Thoth’s mythological origins as well as his actions at a very early stage of the world’s creation may suggest that the god’s historical roots go very deep. As pointed out above, there are depictions of ibis-deities on Pre- and Early Dynastic objects, but it is not clear whether they actually represent Thoth, although it is highly likely. The search for his original cult center does not yield results that are beyond doubt and based on unequivocal sources. From the Old Kingdom onward there are two principle cult centers, Hermopolis Magna (anciently 2mnw) in the 15th Upper Egyptian nome (Wnw, the hare- nome), and Hermopolis Parva (anciently Pr- 9Hwtj-Wpj-RHwj, “House of Thoth Who Has Divided the Two Companions,” at least in the first millennium B.C.) in the 15th Lower Egyptian nome. This parallelism may indicate an intentional systematization by the Egyptians. Passages in the Coffin Texts (later incorporated in the Book of the Dead) suggest that the ibis-god Thoth may have usurped Hermopolis Magna from a baboon-god, Hedj-Wer, by adopting the baboon as another of his manifestations, yet the reconstruction of such an etiology remains highly speculative. Still, the 15th Lower Egyptian nome has the ibis as its standard, which might point to this area being the true home of the ibis-god. [Source: Martin A Stadler , University o Wuerzburg, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

Thoth Image

“Of the Thoth-temples at Hermopolis Magna and Parva not much has survived. At the end of the eighteenth century, the Napoleonic expedition saw at Hermopolis Magna the remains of a pronaos that disappeared thereafter. Horemheb built a pylon there that was three-fourths of the height of his Ninth Pylon at Karnak—an impressive monument for a presumably provincial town . Merenptah erected a temple of Amun in the sacred precinct, but, surprisingly, according to the dedicatory inscription it is Thoth who gracefully accepts this offering and thus dominates over Amun. Ramesses III built several monuments and an enclosure wall there and also “multiplied the divine offerings”. Nectanebo I subsequently commissioned the restoration of the temple of the goddess Useret-Nehemtawy, Thoth’s consort, as well as a 110-meter-long, 55-meter-wide extension of the Thoth temple. Perhaps this work could not be finished during Nectanebo’s reign and was accomplished in the late fourth century B.C..

“Lacking religious texts from the site, little in specific can be said regarding any cult of Thoth that might have been celebrated there: the tomb inscriptions of the fourth-century B.C. high priest of Thoth, Petosiris, are not very informative on that point. Despite such a dearth of information from Hermopolis Magna, the city was anciently considered one of the chief intellectual centers, possibly because of Thoth’s image as god of writing and wisdom. Yet, a closer examination of the available religious texts does not support the view that Thoth’s cult center dominates other Egyptian cities as a place where holy texts were found .

“In almost any Egyptian sanctuary a “Thoth- area” can be identified, but just two additional temples dedicated to Thoth are selected for discussion here, because they show how their Thoth-mythology is oriented towards their environs. At Qasr el-Aguz an early Ptolemaic temple of Thoth is preserved. His particular form there is that of Thoth “the face of the ibis has said” and of Thoth-setem (9Hwtj-stm). The former designation refers to the deceased sacred ibis at Hermopolis Magna and has both oracular and funerary connotations; the latter is not as easily translated. It might refer to Thoth as the libationer (sTj mw- stm) or Thoth as se(te)m- priest and thus presents Thoth as a ritual performer, especially in his function of libationer. Both epithets point to nearby Medinet Habu, where the Hermopolitan ogdoad was believed to be buried and where regular libation rites were performed. In the Nubian temple of Dakke, Thoth’s role in the Myth of the Solar Eye is prominent. Therefore, in this temple he is associated with Shu and Arensnuphis, the brother gods of the Dangerous Goddess, who is the Solar Eye. Both deities are equally involved in appeasing and bringing back the leonine goddess.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024