Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

FAMILY RELATIONS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Nakht family outing

Herodotus reported that 'sons never take care of their parents if they don't want to, but daughters must whether they like it or not." In regards to family and kin relations there were 1) six basic terms through which Egyptians expressed relationships of marriage, descent, and collaterality; 2) principles that regulated marriage and inheritance; different terms for kin groups and family members. Kinship relations in ancient Egyptian social organization—both in Predynastic and Dynastic times— can be examined from the point of view of the peasantry, the elite and in the context of the world of the gods.

Marcelo P Campagno of the University of Buenos Aires wrote:“Kinship relationships constitute a system of social organization based on a cultural interpretation of links between individuals, within the sphere of human reproduction. They have, therefore, both a universal biological aspect and a cultural dimension that exemplify the diversity inherent in the multiple ways in which human beings produce society. Within the framework of this diversity, ancient Egyptian sources deriving from funerary, literary, and religious contexts enable us to assemble the traces of a kinship system that, with some variation, appears to have been remarkably stable through the millennia of ancient Egyptian civilization. [Source: Marcelo P Campagno, University of Buenos Aires, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

RELATED ARTICLES:

FAMILIES IN ANCIENT EGYPT: HOUSEHOLDS, PARENTS AND CHILDREN africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MARRIAGE, DIVORCE AND LOVE IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CHILDREN IN ANCIENT EGYPT: CHILD-REARING, TEENAGERS, HEALTH ISSUES africame.factsanddetails.com

INHERITANCE IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

WOMEN IN ANCIENT EGYPT: STATUS, FEMININITY AND IDEAS ABOUT GENDER africame.factsanddetails.com ;

WOMEN'S ROLES IN ANCIENT EGYPT: MOTHERS, WIVES, WORKERS africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Kinship and Family in Ancient Egypt: Archaeology and Anthropology in Dialogue”

by Leire Olabarria (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Home Life Of The Ancient Egyptians” by Nora E Scott (2006) Amazon.com;

“Households in Context: Dwelling in Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt” by Caitlín Eilís Barrett and Jennifer Carrington (2024) Amazon.com;

“Childhood in Ancient Egypt” by Amandine Marshall and Colin Clement (2022) Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

“The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt: A Genealogical Sourcebook of the Pharaohs” Amazon.com;

”Private Lives of the Pharaohs: Unlocking the Secrets of Egyptian Royalty” by Joyce Tyldesley (2001) Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Egypt” by Gay Robins (1993) Amazon.com;

“Daughters of Isis: Women of Ancient Egypt” by Joyce Tyldesley (1994) Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Kinship Terms in Ancient Egypt

Marcelo P Campagno of the University of Buenos Aires wrote: “The ancient Egyptian kinship system was composed of six basic terms; through these terms the three kinds of relationships inherent in any system of affinity and kinship could be expressed: marriage, descent, and collaterality (siblingship). With respect to marriage—that is, a stable link between two individuals of opposing sex coming from different kin groups—the Egyptians used the terms h(A)y for “husband” and Hmt for “woman/wife.” These terms imply very different semantic fields: while the word h(A)y is written with the determinative of a phallus, associating the role of “husband” with the capacity to engender, the word Hmt is followed by the seated woman determinative, denoting the general meaning of the word (“woman”), and also the more specific one of “wife,” thus constituting a “revealing synonymy” wherein a woman was not strictly defined outside of marriage. The same synonymy occurs in some modern languages, such as French and Spanish. [Source: Marcelo P Campagno, University of Buenos Aires, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Family of the Pharaoh Ptah: On the left is his wife, Ha'tshepest, “the lady full of charms, of grace, and of love "; on the right is his daughter, 'En'euhay, the "favorite of the Pharaoh"; The small figures represent a second daughter and her son, who dedicated the statues

“As for descent terms, Egyptian had two words to refer to lineal-ascendant kin: jt for “father” and mwt for “mother”. These terms were also used to refer to the lineal kin of more distant ascending generations. Thus, both the father’s father and the mother’s father of ego (that is, the point of view taken in describing a relationship) were identified as jt, while mwt was employed to designate individuals related to ego as the father’s mother or the mother’s mother. Similarly, in the descending line, the term sA and its feminine sAt were primarily used for the identification of the “son” and the “daughter” of ego; however, the same terms were also used to refer to the son/daughter of the son/daughter of ego.

“Concerning sibling relationships, and in a more extended sense, collateral kin—that is, ego’s kin, not connected by a lineal ascendant or descendant link—Egyptian had only the term sn and its feminine snt. The term was basically used to indicate the “brother” or “sister” of ego but, in other contexts, it could also designate the link with brothers/sisters of the mother/father of ego (“uncles” and “aunts”), as well as with their sons/daughters (“cousins”), and with the sons/daughters of the brothers/sisters of ego (“nephews” and “nieces”)—and even with more remote collateral kin.

“Although there were no specific Egyptian terms to designate relationships consisting of more than one link (mother + mother, brother + mother), as is the case with our terms “grandmother” or “uncle,” both lineal and collateral consanguineous relationships could be expressed through “compound” or “descriptive” terms, such as mwt nt mwt (“mother’s mother”) or sn (n) mwt.f (“his mother’s brother”). Egyptian kinship terminology expressed a symmetrical system (the same terms are used for paternal and maternal kin) as well as a bilateral one (the descent of ego was traced through both father’s and mother’s kin).

Inscriptions on stelae dated to the Second Intermediate Period that probably come from Abydos provide basic examples of the range of kinship relationships depicted on non-royal monuments, as well as different strategies of display. One stelae lists the father and mother as well as various people designated sn and snt, of the stela owner and the individual named in line 10. Another depicts numerous kin of both the stela owner and his “nurse.” These kin are often designated with compound terms, such as “his brother of his mother” (sn.f n mwt.f) and “the mother of his mother” (mwt nt mwt.f).

“The strong distinction between kin connected to ego by descent (“fathers” and “mothers” being in the ascendant line, and “sons” and “daughters” being in the descendant line) and other kin (all of them subsumed under the collateral term sn/snt) may suggest that two different criteria for kin membership coexisted. As stated by Judith Lustig, “unlike the lineal terms which express difference in status between alter and ego, . . . persons called sn/snt may be conceptualized as structurally equivalent to ego”; indeed, the term sn/snt could also be used to refer to “friends,” “lovers,” “equals,” or other individuals related to ego through a link of horizontal proximity, as in the case of the Old Kingdom title sn Dt, “brother of the estate” . In this sense, it could be argued that the Egyptian perception of kinship emphasized the specific link between each individual and his or her kin network through descent against the whole network of kinship links—the kindred—which displayed a broad conception of collateral ties.”

Tutankhamun's (King Tut's) probable relatives

Kin Groups and Social Organization in Ancient Egypt

Marcelo P Campagno of the University of Buenos Aires wrote: “The core of the family comprised the married couple, unmarried children, and other female kin (aunts, sisters, widowed mothers) who had lost or never formed their own family unit. The mode of residence appears to have been of a neolocal type—that is, any new couple constituted a new nuclear family and established a new, independent home, as we see in Ani’s instruction to his son: “[3,1] Take a wife while you’re young, that she make a son for you” . . . [6,6] Build a house or find and buy one”. However, in First Intermediate Period sources, the emphasis on the preservation of the paternal house (pr jt) suggests that the eldest son could stay in the home. In any case, perceptions of the nuclear family probably predominantly reflected the ideals of the elite, who lived in urban settings, rather than those of the rural population, among which various forms of extended families likely prevailed. [Source: Marcelo P Campagno, University of Buenos Aires, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“The Egyptian language had a remarkably extensive set of terms for kin groups larger than nuclear families. From the late Old Kingdom on, the term Abt referred to households or extended families, while the term hAw identified the close kin of an individual. From the Middle Kingdom on, several terms were in use, such as mhwt (clan or extended kin group), wHyt (kin group in village contexts), Xr (kin group living in the same household), and hnw (all members of a household). During the New Kingdom, dnjt or dnwt was used to refer to a familial kin group. Moreover, terms with broader meanings, such as Xt (group, corporation, generation) or wnDw(t) (group, troop, gang), were sometimes used to refer to kin groups.

“The existence of terms like these that refer to larger kin groups is significant because it points toward the prominence of kinship in ancient Egyptian social organization. Kinship links were likely of great importance in the articulation of social ties both before and after the emergence of the state in the Nile Valley. In accordance with anthropological models of non-state societies, it can be hypothesized that, during Predynastic times, kinship constituted the main axis of social organization in village communities. Archaeological evidence seems to support this assumption: the grouping of tombs in clusters in cemeteries at various sites, such as Badari, Armant, Naqada, and Hierakonpolis, is similar to funerary practices known through ethnographic evidence, where such a distribution of burials reflects contemporaneous descent groups; the parallelism in the shapes of Predynastic tombs and houses (both were oval or rounded from the earliest times but included rectangular shapes from Naqada I on) may reflect a perception of continuity between the two domains, which in turn may suggest the perceived symbolic survival of the dead kin as members of the community; and indeed, the disposition of grave goods around the deceased could reflect notions of reciprocity, which are at the heart of kinship relations.

“In Dynastic times, the state introduced a new mode of social organization based on the monopoly of coercion, but kinship continued to be a decisive factor in many social realms. Some pointers hint at its importance among the peasantry: the organization of agricultural tasks in family units, practices involving cooperation (that is reciprocity) in the field labor, such as we see in tomb representations or in the management of irrigation, the (likely) prominent role of village elders in local decision-making, the scant interference of the state in intra- community matters—all these suggest the importance of kinship logic in the articulation of social dynamics in peasant villages.

“The importance of kinship can also be seen in state-elite contexts. Beyond the state’s power to exert the monopoly of coercion over society’s subordinate majority, the integration of the state elite itself was accomplished through kinship ties. The inheritance of the throne from father to son, matrimonial alliances as strategic reinforcements of cohesion among the elite, the possibility of “making” new kin members through mechanisms of adoption, the expression of rank in kinship terms related to the monarch (as in the case of the title sA nsw, literally “king’s son”), as well as the placement, around a principle tomb, of multiple burials of probable kin-group members, as is found in the Old Kingdom cemeteries at Abusir and Elephantine, evoke the importance of kinship logic in the articulation of the nucleus of state society.”

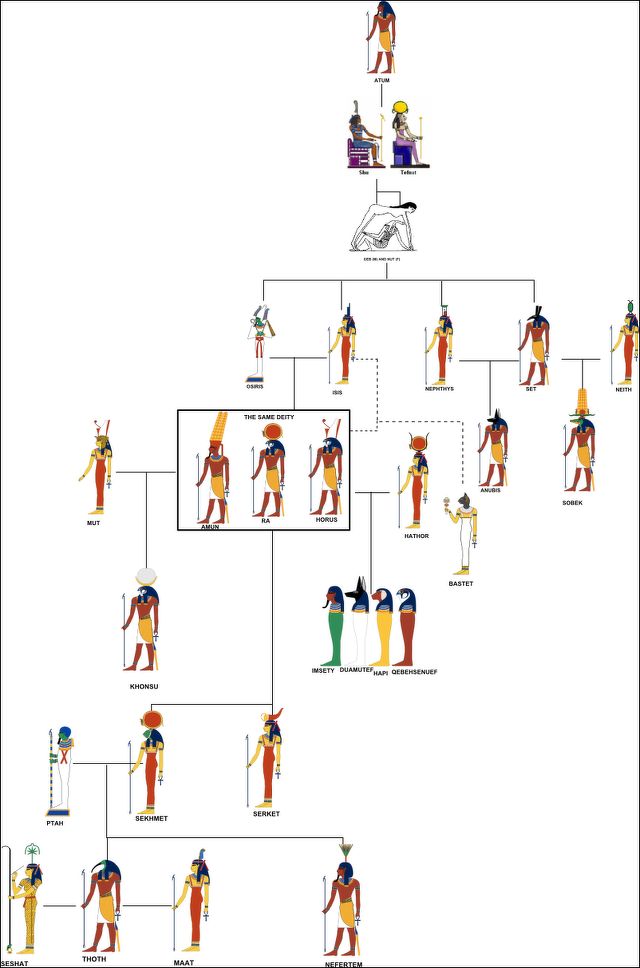

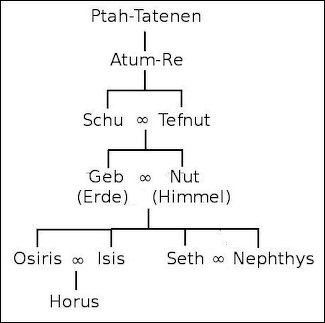

Relationship between the main Memphis gods

Kin Relations Reflected in Egyptian Gods

Marcelo P Campagno of the University of Buenos Aires wrote: “Additionally, the relevance of kinship can be detected in the Egyptian world-view, especially in the way links between the king and the gods, and among the gods, were expressed. On the one hand, the king was referred to in many contexts as the son of diverse deities. From the 4th Dynasty on, the monarch incorporated into his titulary a new name marking his status as sA Ra, “Son of Ra,” directly connecting him to the sun-god. In the Pyramid Texts, the king was presented as the son of many gods, such as Atum, Nut, Geb, Isis, and Osiris. During the New Kingdom, pharaohs were recognized as bodily sons of Amun. In all these relationships that the king had with the gods, one idea is emphasized: the king was not only a god himself but also the kin of the gods. [Source: Marcelo P Campagno, University of Buenos Aires, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Links among the gods themselves were also expressed through kinship ties, as evidenced, for example, in the way the gods of the Heliopolitan Ennead were related to one another: Atum created a brother-sister pair (Shu and Tefnut), who begot another brother- sister pair (Geb and Nut), who in turn engendered four children (Osiris, Isis, Seth, and Nephthys); kinship links were then projected forward to the next generation when Horus, the posthumous son of Osiris, fought and subdued his uncle Seth (who had committed fratricide against Osiris), thus attaining the kingship. Beyond the Ennead, other deities were also related to one another through kinship links, most notably as triads of father, mother, and child, such as those of Sobek, Hathor, and Khons in Kom Ombo; of Amun, Mut, and Khons in Thebes; of Horus, Hathor, and Ihi in Dendara; and of Ptah, Sakhmet, and Nefertem in Memphis.”

Lack of Interest in Genealogy in Ancient Egypt

It is well known from the inscriptions in the Egyptian tombs, that nothing that was adapted to increase the fame of the deceased would be lightly passed over in silence. Yet amongst the numerous inscriptions of the Old and Middle Kingdom, we rarely find any praise of the famous ancestors of the deceased; as a remarkable exception a high priest of Abydos boasts that he had built his tomb “in the midst of those of his fathers to whom he owed his being, the nobles of ancient days." “The family of the deceased is scarcely spoken of, even the grandfather being rarely mentioned. When the deceased was descended from a king, he tells posterity of his genealogy; but this is an exceptional case, e.g. in one of the tombs of the Old Kingdom, in the place where the name of the deceased is usually given, we find this genealogy." [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The king Snefru.

His great legitimate daughter Nefrctkau.

Her son, Neferma'at, the high treasurer.

His son, Snefru-ch'af, the high treasurer, priest of Apis, nearest friend

We see from the defectiveness of this genealogy, in which even the name of the grandfather is not given, how little Snefru-ch'af thought of his family history; the only fact that interested him was that he was related to a Pharaoh. The same holds good in later times; it is always the individual who is spoken of, very seldom the race or family. It is only during the latest epoch of Egyptian history, in the times of the Ethiopian kings, of the Psammetichi and of the Persians, when people gloried in the remembrance of the former greatness of the nation, that we meet with complete genealogical trees; it was natural that at this period men should be glad if possible to boast of direct descent from an official of king Ramses.

Another circumstance confirms the above statement. In the course of generations, a nation possessing genealogical sense unconsciously forms surnames, even when they only consist of vague appellations, such as are used by the old Bedouin families. There is no trace of such names amongst the Egyptians, not even amongst the noble families of the Middle Kingdom. We reach the decadence of the Egyptian kingdom before we meet with even a tendency to use family names; in the time of the foreign Libyan rulers the descendants of the old family of the Pharaohs called themselves “sons of King Ramses," thus forming a race of the “sons of Ramses," the “Ramessides."

Names therefore with the Egyptians were entirely individual, and if we may say so, lack historical significance. Notwithstanding they offer much that is interesting, and a closer study of them will reward an attentive student. Names were of course subservient to fashion, and very few were in common use at all periods, though the ideas they expressed have much similarity.

If an official succeeded in a brilliant career, it was the maternal grandfather who took the most interest: “When he is placed at the head of the court of justice, then the father of his mother thanks God."" Under the New Kingdom we hear of a young officer who is received into the royal stables, “for the sake of the father of his mother," and when obliged to go to the wars, he “gave his property into the charge of the father of his mother."

Family Served as a Social Safety Net in Ancient Egypt

Based on texts found at Deir el-Medina, a village of artisans near the Valley of the Kings, Anne Austin wrote in the Washington Post: In cases where these provisions from the state were not enough, the residents of Deir el-Medina turned to one another. Personal letters from the site indicate that family members were expected to take care of one another by providing clothing and food, especially when a relative was sick. These documents show us that caretaking was a reciprocal relationship between direct family members, regardless of gender or age. Children were expected to take care of both parents just as parents were expected to take care of all of their children. [Source: Anne Austin, Washington Post, February 17 2015. Anne Austin is a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University ***]

“When family members neglected these responsibilities, there were fiscal and social consequences. In her will, the villager Naunakhte indicates that even though she was a dedicated mother to her children, four of them abandoned her in her old age. She admonishes them and disinherits them from her will, punishing them financially, but also shaming them in a public document made in front of the most senior members of the Deir el-Medina community. ***

“This shows us that health care in Deir el-Medina was a system with overlying networks of care provided through the state and the community. While workmen counted on the state for paid sick leave, a physician, and even medical ingredients, they depended equally on their loved ones for the care necessary to thrive in ancient Egypt.” **

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024