Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

FAMILIES IN ANCIENT EGYPT

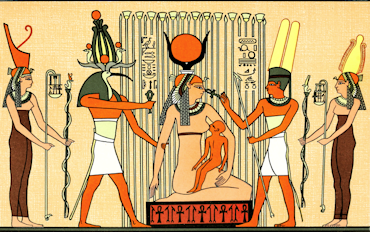

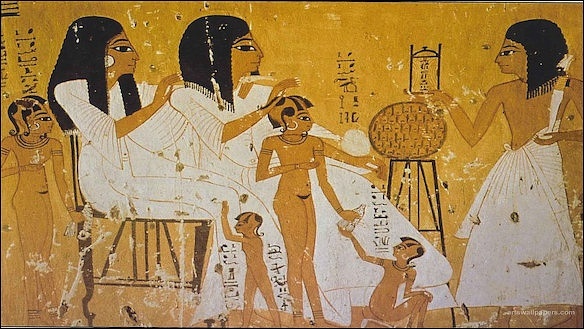

Isis suckling Horus According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “The basic family unit in ancient Egypt was the nuclear family. The family was broken down into roles that each would play in order for things to run smoothly. The father was the one who would work all day. In smaller households the mother was in charge of all things pertaining to the house. Cooking, cleaning and watching the children were all her responsibilities. In some larger homes servants served as maids and midwives to help the mother. Ancient Egypt was a patrilineal society with people’s histories being traced through their father’s background. Legal documents have shown that and and property was inherited through the males of the family. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

It was considered the greatest happiness to possess children, and the relationship between parents and children offers us a delightful picture of Egyptian family life. Monogamy was the norm in ancient Egypt. One woman alone was the legitimate wife of the husband, “his dear wife," “the lady of the house "; yet when we obtain a glimpse into the interior of a well-to-do household, we find also “beautiful singers “and other attendants in the “house of the women." The relationship between husband and wife appears to us at all times to have been faithful and affectionate. When they are represented together, we frequently see the wife with her arm tenderly round her husband's neck, the children standing by the side of their parents, or the youngest daughter crouching under her mother's chair. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

A letter from a minor landowner to his steward, conveying instructions about a misbehaving servant reads: “Now have that housemaid Senen thrown out of my house – see to it – on whatever day Sahathor reaches you. Look, if she spends a single day (more) in my house, act! You are the one who lets her do bad things to my wife. Look, how have I made it distressful for you? What did she do against you (to make) you hate her? And greetings to my mother Ipi a thousand times, a million times. And greetings to Hetepet and the whole household and Nefret. Now what is this, bad things being done to my wife? Enough of it! Are you given equal rights with me? It would be good if you stopped.”“ [Source: Nathaniel Scharping, Discover, September 22, 2016 =]

RELATED ARTICLES:

FAMILY RELATIONS AND KINSHIP IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MARRIAGE, DIVORCE AND LOVE IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CHILDREN IN ANCIENT EGYPT: CHILD-REARING, TEENAGERS, HEALTH ISSUES africame.factsanddetails.com

INHERITANCE IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

WOMEN IN ANCIENT EGYPT: STATUS, FEMININITY AND IDEAS ABOUT GENDER africame.factsanddetails.com ;

WOMEN'S ROLES IN ANCIENT EGYPT: MOTHERS, WIVES, WORKERS africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Households in Context: Dwelling in Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt” by Caitlín Eilís Barrett and Jennifer Carrington (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Home Life Of The Ancient Egyptians” by Nora E Scott (2006) Amazon.com;

“Kinship and Family in Ancient Egypt: Archaeology and Anthropology in Dialogue”

by Leire Olabarria (2020) Amazon.com;

“Childhood in Ancient Egypt” by Amandine Marshall and Colin Clement (2022) Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

“The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt: A Genealogical Sourcebook of the Pharaohs” Amazon.com;

”Private Lives of the Pharaohs: Unlocking the Secrets of Egyptian Royalty” by Joyce Tyldesley (2001) Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Egypt” by Gay Robins (1993) Amazon.com;

“Daughters of Isis: Women of Ancient Egypt” by Joyce Tyldesley (1994) Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Households in Ancient Egypt

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: “The household was the basic unit of the Egyptian social organization, but its composition varies depending on administrative or sociological considerations: administrative records focus on nuclear families while private sources stress the importance of the extended family. Households included people linked by family ties but also serfs, clients, dependants and “friends”, sometimes encompassing hundreds of persons. As for their sources of wealth, they consisted of patrimonial and institutional goods, and household strategies tried to keep and enlarge them within the family. Nevertheless, menaces like debts, shortages or disputes over inheritances could lead them to their disappearance. Hence the importance of ideological values which tied together their members while celebrating their cohesion, autonomy and genealogical pride. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

Nakht family outing

“The Egyptian term pr (“house” or “household” being its commonest designations) appears in administrative documents as the basic unit of social organization, and the rich ideological nuances it bore are particularly evident in its inclusion in phraseology for certain territorial units (e.g., pr 2ww “the domain of [the governor] Khuu”) or even kingdoms (e.g., pr 2ty “the House of Khety,” the Herakleopolitan kingdom in the First Intermediate Period). It is not insignificant that both the pharaoh and the state were equated with the notion of the pr-aA “the big house,” and Egyptologists such as Lehner have argued that the entire Egyptian state should be interpreted as a “household of households” instead of a heavily centralized state. However, administrative and sociological images of households could diverge widely. Censuses, for example, tended to focus on nuclear families, thus giving a partial and biased picture of Egyptian society because their main purpose was to record fiscal information (manpower and resources available in fixed, accessible units) rather than changing) social structures: “I assessed households at the (appropriate) numbers thereof and I have separated out the gangs from their households”.

Founding a household was a highly praised act in Pharaonic times, celebrated both in teachings and literature. The troubled times at the end of the third millennium introduced many ideological innovations in private beliefs and self-presentation, with emphasis now put on one’s own initiative, autonomy, and achievements. The concept of restoring the family household (grg pr jt “to restore the house of the father”) became quite popular, and the protagonists usually stated that they had found their family households ruined, but had successfully rebuilt and enriched them, and subsequently transferred them to their heirs, thus ensuring the continuity of their lineage. What is more, the same ideology outlined the piety of the protagonists by asserting that they had given houses to disadvantaged people such as orphans, young women, or, simply, persons deprived of a household. Finally, their own merit was further highlighted because of their condition as the youngest child risen from a family with many heirs. Such an ideal was, nevertheless, confronted with much harsher realities, when debts contracted in hard times, hazardous economic decisions, contested or problematic inheritances, or basic penury could result in the loss of family property or in the destruction of a household .

“Occasional archaeological and textual evidence reveals the importance of extended families and kinship, an aspect hardly evoked at all in official sources. This does not mean that households were highly cohesive, hyper- resilient structures either. Inner and external threats tested their endurance and opened the way for change: on the one hand, conflicts of interest between the demands of kin and the particular ambitions of individuals could lead to the disintegration of a formerly solid household, whereas heritage concerns might encourage special arrangements aimed at the preservation of family assets, as in cases where brothers held (together) fields and houses. Other risks, which weighed heavily on the cycles of family reproduction (especially of peasants), and household strategies and their viability in the long term, were debts and serfdom, whereas elite households faced specific threats such as falling from favor or factional discord—including the murder of entire families. What emerges from these considerations is that the very notion of “household” encompasses a broad range of situations, subject to changes over time, and that it would be misleading to found its study only on administrative sources.”

Household Composition in Ancient Egypt

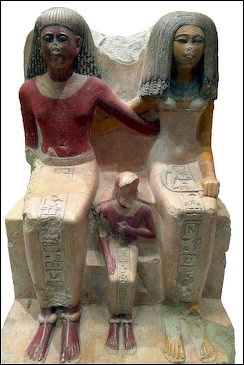

priest with his wife and child

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: “The composition of households varied greatly depending on their social status, as the Egyptian vocabulary displays a wide range of terms, from those referring strictly to blood relations to those including individuals linked to the household as co-residents, serfs, clients, “friends,” or dependants—their nuances being quite often difficult to specify. Heqanakht, a moderately well-off official of the Middle Kingdom, mentions eighteen people belonging to his household, including his mother, his second wife, his son, two daughters, his older aunt or daughter, his youngest brother, his foreman (and his dependants), three cultivators, and three female servants . The contemporary general Sebeki represents in his stela his wife, two sons, two daughters, his brother, his sister, his mother, her (second?) husband with his five sons, his mother, the daughter of his mother, seven cultivators, ten female servants, and three other men. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“As for the households of the highest members of the elite, they could integrate hundreds of people (including dozens of servants; according to Middle and New Kingdom sources, from 60 to as many as 150 serfs were transferred to dignitaries), many of whom are depicted in their tombs. But archaeological evidence suggests that the average number of people living in a small to medium house would have been six, and an average of two or three children living with their parents seems logical. One or two more people—either dependant relatives or servants—were possibly also resident. Therefore it can be estimated that the number of people living in such a house was five to eight, with an average of six. Hellenistic censuses show that an Egyptian household included two adults and two children on average.

“In the case of high officials a formal distinction was made between their family household and the domains allowed by the state. Thus, Hapidjefa of Siut, in the early Middle Kingdom, distinguished carefully between his own family household (pr jt, “the house of the father”) and the domain granted to him as a reward for his position as governor (pr HAtj-a, “the house of the governor”); domains of this kind usually included not only provisions but also serfs, fields, specialized workers, and a suitable residence . Leaving aside these rather specific cases, the autonomous household is thought to have been an ensemble formed by an extended family (Abt) and their fields (AHwt) put under the authority of the residence (pr/Hwt) of the household head, an ideal echoed by the ritual texts.

“A further characteristic of the composition of a household is that it changed according to the life cycle and attendant circumstances of its members. Middle Kingdom papyri from Lahun show, for example, that the (nuclear) family of soldier Hori included his wife and his young son. Later on, after the death of his father, he appears as the head of a household also encompassing his mother and five aunts, thus suggesting that, in fact, his family and that of his father shared residence, that multiple family households were acknowledged by the administration if only one male family head was present in the household and, consequently, that two adult males in one household represented two unconnected units from an administrative point of view. At an even later period, Hori seems to have died and his son Sneferu became the head of the household, which now consisted of six people. Another example, from late New Kingdom Deir el-Medina, describes a lady living in her husband’s house while, later on, she and her daughter lived in the house of a married son without children. Outside these institutional settlements, where only one man could be (administratively) the head of a household, women are occasionally attested as heads-of-household in rural environments, as in the case of the 4th Dynasty household (pr.s “her house”) of the lady Tepi, made up of a scribe, a letter carrier (jrj mDAt), and a “property manager” (jrj jxt).”

Family Composition in Ancient Egypt

Nakht family outing

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: “The nuclear family has been traditionally regarded as the core of Pharaonic social structure on the basis of architecture (both civil and funerary), iconography, and administrative records. Nevertheless, architectural evidence comes mainly from a limited number of sites, such as Deir el- Medina, Lahun, and el-Amarna, often designed by the state according to an orthogonal grid and created to fulfil specific purposes. But a careful re-examination of their remains, as in the case of Lahun, shows nevertheless that houses apparently planned for nuclear families were subsequently modified by their inhabitants and adapted to the needs of extended families. As for private tombs and statuary, the iconography stresses the central role played by the owner, his wife, and sons; however, secondary shafts and inhumations were also arranged for other members of his kin, a characteristic mainly visible in provincial mastabas, whose multiple burials prove that they were often designed for the needs of extended families. Finally, it cannot be excluded that dwellings housing nuclear families in villages, towns, and cities were in fact grouped by neighborhoods or residential quarters mainly inhabited by extended families: a passage in the Instruction of Papyrus Insinger, for instance, lists the house (at), the extended family (mhwt), the village/town (tmj), and the province, in ascending order . Some archaeological evidence has also been adduced. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“In any case, the collapse of the state at the end of the third millennium was followed by frequent mentions of the extended family (Abt) both in private inscriptions and funerary texts. Taking care of one’s Abt figures prominently in monumental texts, while some formulae in the Coffin Texts enumerate the categories of people encompassed by this term and constituting the household of the deceased; its core was formed by the deceased’s father, mother, children, siblings, and serfs (mrt), as well as by other people related to him by social, not familial, links, such as fellow citizens (dmj), companions (jrj-rmnw), friends (xnmsw), loved ones (mryt), associates (smAw), and concubines (mt-Hnwt). Broadly speaking, a distinction was made between his extended family (Abt, including his serfs) and his dependants, subordinates, and acquaintances (hnw), a distinction outlined by other sources where the extended family (hAw, also including the serfs, bAkw) together with the friends (xnmsw) constituted rmTj nbt “all my people”.

“Other late third-millennium sources, such as some execration texts, confirm this picture as they also evoke, for the first time, the members of a household instead of the traditional lists of Egyptian and foreign enemies. Like the ink inscriptions found on many jars at the necropolis of Qubbet el-Hawa, they provide detailed insight into the composition and social life of the households of local high officials, their tombs being foci of rituals and the deliveries of offerings tying together their kin as well as a dense web of relations, including clients and eminent local personalities. The dead were also considered members of the household (a Late Period stela explicitly represents the deceased relatives among the extended family [Abt] of a lady), and petitions were addressed to them in order to solve domestic problems. Later on, during the Middle Kingdom, private stelae evoked complex genealogies and were often placed in family cenotaphs; in some cases, they took the form of long lists of what seems to be the heads of households linked together by unspecified ties.

“New Kingdom texts mention individuals involved in lawsuits over family property held by a group of brothers or by a group of descendants of a common ancestor. Finally, during the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, censuses list only nuclear families while private archives reveal that personal affairs and sales concerned, in fact, other relatives as well as the members of extended families. To sum up, Egyptian households should not be considered limited to nuclear families as they were frequently multifaceted social networks embracing other relatives, serfs, clients, subordinates, and dependants, especially at the uppermost levels of Pharaonic society. Thus, the silos in the richest villas of el- Amarna could be interpreted both as indicators of status and as the foci of a redistributive system involving not only their owners but also their relatives and dependants, also considered members of the household . “Middle class” papyri and houses show that the same principle was operative, although on a smaller scale, in the households of relatively modest officials and individuals.”

Family Relations and Kinship in Ancient Egypt

Herodotus reported that 'sons never take care of their parents if they don't want to, but daughters must whether they like it or not." In regards to family and kin relations there were 1) six basic terms through which Egyptians expressed relationships of marriage, descent, and collaterality; 2) principles that regulated marriage and inheritance; different terms for kin groups and family members. Kinship relations in ancient Egyptian social organization—both in Predynastic and Dynastic times— can be examined from the point of view of the peasantry, the elite and in the context of the world of the gods.

Marcelo P Campagno of the University of Buenos Aires wrote:“Kinship relationships constitute a system of social organization based on a cultural interpretation of links between individuals, within the sphere of human reproduction. They have, therefore, both a universal biological aspect and a cultural dimension that exemplify the diversity inherent in the multiple ways in which human beings produce society. Within the framework of this diversity, ancient Egyptian sources deriving from funerary, literary, and religious contexts enable us to assemble the traces of a kinship system that, with some variation, appears to have been remarkably stable through the millennia of ancient Egyptian civilization. [Source: Marcelo P Campagno, University of Buenos Aires, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

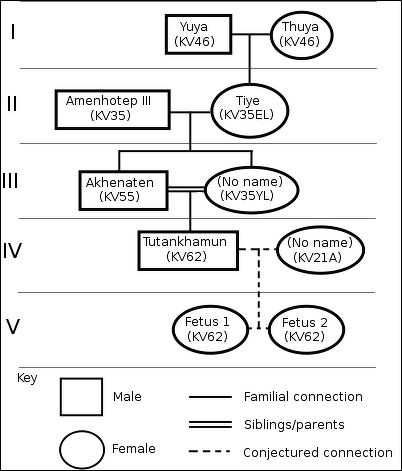

Tutankhamun's (King Tut's) probable relatives

Marcelo P Campagno of the University of Buenos Aires wrote: “The ancient Egyptian kinship system was composed of six basic terms; through these terms the three kinds of relationships inherent in any system of affinity and kinship could be expressed: marriage, descent, and collaterality (siblingship). With respect to marriage—that is, a stable link between two individuals of opposing sex coming from different kin groups—the Egyptians used the terms h(A)y for “husband” and Hmt for “woman/wife.” These terms imply very different semantic fields: while the word h(A)y is written with the determinative of a phallus, associating the role of “husband” with the capacity to engender, the word Hmt is followed by the seated woman determinative, denoting the general meaning of the word (“woman”), and also the more specific one of “wife,” thus constituting a “revealing synonymy” wherein a woman was not strictly defined outside of marriage. The same synonymy occurs in some modern languages, such as French and Spanish. [Source: Marcelo P Campagno, University of Buenos Aires, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

See Separate Article: FAMILY RELATIONS AND KINSHIP IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Relationship Between Father and Son in Ancient Egypt

During all ancient Egyptian periods it was the heartfelt wish on every father's part that he should leave his office to his son," that “his child should sit in his chair after he was gone; it was also the son's sacred duty “to cause his father's name to live." In both particulars, the gods had left an example for men of all times; Horus had avenged his deceased father Osiris, and justified his name against the accusations of Seth, for he himself had ascended the “throne of his father," and had put the Atef crown of his father on his own head. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

A father could not do very much to insure that his son should succeed him, Pharaoh had to decide that matter with his counsellors, but they (if they were piously inclined), considered it their duty as far as possible to follow the dictates of this pious claim, and to “place every man on the throne of his father." The duty of the son was the easier to fulfil, on account of the manner in which he had to cause his father's name to live: viz. to maintain his tomb and to offer the necessary sacrifices there on festival days.

More than one pious son assures us in his autobiography that he had fulfilled these sacred duties; e.g. the nomarch Chnemhotep relates: “I have caused the name of my father to increase, and have established the place for his funeral worship and the estate belonging thereto. I have accompanied my statues {i.e. those of the family on days of procession) into the temple. I have brought to them their offerings of pure bread, beer, oil, and incense. I have appointed a funerary priest, and endowed him with land and labourers. I have established offerings for the deceased on every festival of the Necropolis." These duties towards the deceased descended in direct line to the head of the family, but at the same time the obligation rested on the other members, even of later generations; they also had to keep up the established worship, and to honour their ancestors especially had to honour their ancestors, “the forefathers of the king." In spite of this reverence for their ancestors, we doubt whether, with the exception of the royal family, there existed much family pride amongst the ancient Egyptians.

Instruction of Ptah-Hotep (2200 B.C.) on Being a Good Father

The Instruction of Ptahhotep is an ancient Egyptian literary composition written by the Vizier Ptahhotep, during the rule of King Izezi of the Fifth Dynasty. Regarded as one of the best examples of wisdom literature, specifically under the genre of Instructions that teach something, of Ptahhotep addresses various virtues that are necessary to live a good life in accordance with Maat (justice) and offers insight into Old Kingdom — and ancient Egyptian — thought, morality and attitudes. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Instruction of Ptahhotep ( c. 2200 B.C.) reads: “If you are wise, look after your house; love your wife without alloy. Fill her stomach, clothe her back; these are the cares to be bestowed on her person. Caress her, fulfil her desires during the time of her existence; it is a kindness which does honor to its possessor. Be not brutal; tact will influence her better than violence; her . . . behold to what she aspires, at what she aims, what she regards. It is that which fixes her in your house; if you repel her, it is an abyss. Open your arms for her, respond to her arms; call her, display to her your love. [Source: Charles F. Horne, “The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East” (New York: Parke, Austin, & Lipscomb, 1917), Vol. II: Egypt, pp. 62-78, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt, Fordham University]

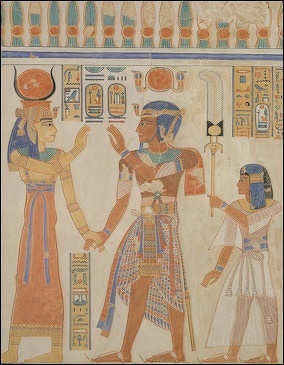

Ramses III and Prince Amenherkhepesef before Hathor

“Treat your dependents well, in so far as it belongs to you to do so; and it belongs to those whom Ptah has favored. If any one fails in treating his dependents well it is said: "He is a person . . ." As we do not know the events which may happen tomorrow, he is a wise person by whom one is well treated. When there comes the necessity of showing zeal, it will then be the dependents themselves who say: "Come on, come on," if good treatment has not quitted the place; if it has quitted it, the dependents are defaulters.

“If you take a wife, do not . . . Let her be more contented than any of her fellow-citizens. She will be attached to you doubly, if her chain is pleasant. Do not repel her; grant that which pleases her; it is to her contentment that she appreciates your work.

“To attend therefore profits the son of him who has attended. To attend is the result of the fact that one has attended. A teachable auditor is formed, because I have attended. Good when he has attended, good when he speaks, he who has attended has profited, and it is profitable to attend to him who has attended. To attend is worth more than anything else, for it produces love, the good thing that is twice good. The son who accepts the instruction of his father will grow old on that account. What Ptah loves is that one should attend; if one attends not, it is abhorrent to Ptah. The heart makes itself its own master when it attends and when it does not attend; but if it attends, then his heart is a beneficent master to a man. In attending to instruction, a man loves what he attends to, and to do that which is prescribed is pleasant. When a son attends to his father, it is a twofold joy for both; when wise things are prescribed to him, the son is gentle toward his master. Attending to him who has attended when such things have been prescribed to him, he engraves upon his heart that which is approved by his father; and the recollection of it is preserved in the mouth of the living who exist upon this earth.

“When a son receives the instruction of his father there is no error in all his plans. Train your son to be a teachable man whose wisdom is agreeable to the great. Let him direct his mouth according to that which has been said to him; in the docility of a son is discovered his wisdom. His conduct is perfect while error carries away the unteachable. Tomorrow knowledge will support him, while the ignorant will be destroyed.

Children in Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptians revered children and children were a valued part of ancient Egyptian society. Examples of child abuse are extremely rare. By contrast, Joseph Castro of Live Science wrote, “though Romans loved their kids immensely, they believed children were born soft and weak, so it was the parents' duty to mold them into adults. They often engaged in such practices as corporal punishment, immobilizing newborn infants on wooden planks to ensure proper growth and routinely bathing the young in cold water as to not soften them with the feel of warm water.” [Source: Joseph Castro, Live Science, May 28, 2013]

Despite the fact that children played a central part in the lives of ancient Egyptians, pregnant women are seldom depicted. One of the few examples depicts queen Ahmose in the Deir el-Bahri divine birth sequence. In Sudan, a skeleton of an adult Nubian female was found with baby's skeleton lying across her ankles

Joyce M Filer wrote for the BBC: “Many women died as young adults, and childbirth and associated complications may well have been the cause.Although Egyptians 'experimented' with contraception-using a diverse range of substances such as crocodile dung, honey and oil-ideally they wanted large families. Children were needed to help with family affairs and to look after their parents in their old age. This would have led to women having numerous children, and for some women these successive pregnancies would have been fatal. Even after giving birth successfully, women could still die from complications such as puerperal fever. It was not until the 20th century that improved standards of hygiene during childbirth started to prevent such deaths. [Source: Joyce M Filer, BBC, February, 17, 2011 |::|]

See Separate Article: CHILDREN IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Protective Childbirth Tattoos Found on Ancient Egyptian Mummies

Some ancient Egyptian mothers got tattoos that were likely meant to protect them during childbirth and during the postpartum period, an analysis of their mummies reveals. Kristina Killgrove wrote in Live Science; At the New Kingdom site of Deir el-Medina (1550 B.C. to 1070 B.C.), researchers Anne Austin and Marie-Lys Arnette have discovered that tattoos on ancient flesh and tattooed figurines from the site are likely connected with the ancient Egyptian god Bes, who protected women and children, particularly during childbirth. They published their findings in October 2022 in the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. [Source: Kristina Killgrove, Live Science November 14, 2022

The discovery of at least six tattooed women at Deir el-Medina was surprising. "It can be rare and difficult to find evidence for tattoos because you need to find preserved and exposed skin," study lead author Anne Austin, a bioarchaeologist at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, told Live Science. "Since we would never unwrap mummified people, our only chances of finding tattoos are when looters have left skin exposed and it is still present for us to see millennia after a person died. "

The new evidence that Austin discovered came from two tombs that she and her team examined in 2019. Human remains from one tomb included a left hip bone of a middle-aged woman. On the preserved skin, patterns of dark black coloration were visible, creating an image that, if symmetrical, would have run along the woman's lower back. Just to the left of the horizontal lines of the tattoo is a depiction of Bes and a bowl, imagery related to ritual purification during the weeks after childbirth.

The second tattoo comes from a middle-aged woman discovered in a nearby tomb. In this case, infrared photography revealed a tattoo that is difficult to see with the naked eye. A reconstruction drawing of this tattoo reveals a wedjat, or Eye of Horus, and a possible image of Bes wearing a feathered crown; both images suggest that this tattoo was related to protection and healing. And the zigzag line pattern may represent a marsh, which ancient medical texts associated with cooling waters used to relieve pain from menstruation or childbirth, according to Austin.

In addition, three clay figurines depicting women's bodies that were found at Deir el-Medina decades ago were reexamined by study co-author Marie-Lys Arnette, an Egyptologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, who suggested that they too show tattoos on the lower back and upper thighs that include depictions of Bes.

The researchers concluded in their paper that "when placed in context with New Kingdom artifacts and texts, these tattoos and representations of tattoos would have visually connected with imagery referencing women as sexual partners, pregnant, midwives, and mothers participating in the post-partum rituals used for protection of the mother and child. "

Patronage and Economic Pressures on Egyptian Families

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: “Self- sufficiency was hardly achievable for many Egyptians, who were thus obliged to depend on powerful or influential fellow citizens and to join their patronage networks to the point of being considered part of their households. In other cases, such networks provided a kind of “vertical integration” in addition to the “horizontal” one constituted by family and neighbors, thus linking high officials to minor ones, local potentates to courtiers, and officials to ordinary workers and citizens. A New Kingdom ostracon, for instance, reports that fugitive oarsmen were found in the company of prominent officials at different locations in the Delta. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

family of three --- one man, two women

“The economic strategies followed by Egyptian households naturally depended on their status and wealth. Nevertheless, certain points deserve attention. As stated previously, self- sufficiency was an ideal hardly attainable for many Egyptians, who were thus forced to borrow from richer neighbors, to work (at least part-time or seasonally) for institutions and wealthier neighbors, or to enter into patronage networks that perpetuated social inequalities between households. Late third- millennium sources evoke these problems, probably current in a rural environment: on the one hand, wealthy individuals boasted about their autonomy and acquisitions when lending staple cereals, yokes, and livestock, and acquiring fields, serfs, and flocks, especially in periods of crisis; on the other hand, indebted people lost their goods and became the serfs of other people.

“Young women seem to have been particularly vulnerable and the first members of indebted households to be enslaved. It is also quite possible that debts and loans reinforced the influence of local potentates and lubricated social ties between peers, as is exemplified in the archive of Heqanakht: up to twelve persons owed Heqanakht cereals, while he himself leased land from well-off neighbors. In some cases, the sources offer a glimpse of individual strategies: thus one Ikeni bought land from several persons (mostly priests) during a troubled year (lit. “the bad time”; in one case the field of a lady was actually sold by a male kinsman of her household). Most of the fields were located “by the well of Ikeni,” therefore suggesting that he pursued the control of land around a water source of his own. As for the lady Tsenhor, she built up a modest (but not unsubstantial) asset: she acquired a slave, obtained a building area, inherited part of a building, a cow, and a field of 11 arouras from her father, and, finally, she acquired some income as a choachyte, or mortuary priest. The detailed archive of Heqanakht also provides a good picture of the composition of the household of a well-off Egyptian: it included about eighteen persons, a sizeable amount of land (between 55 and 110 arouras) and 35 head of cattle, and its owner was also involved in other lucrative activities such as renting out and leasing land, and lending cereals to neighbors. Other well-documented socio-economic activities in modest households include the domestic production of women (especially clothes), small credit, exchanges of gifts and agricultural products, and transactions between villagers. Wealthier households participated in more profitable activities like leasing land from temples, buying and selling real estate (especially urban houses), or lending money, as late legal manuals and contracts show.

“If bad years tested the resilience of households, inheritances and the subsequent fragmentation of property holdings (including family land and houses) were another threat, which could be avoided through the collective possession of land and buildings, such as by creating (transmissible) shares giving rights to a part of a house or of the incomes from a field. Conflicts of interest between an official and his kin about the institutional goods granted to him were not unknown, for example, in situations where the (extended) family claimed the right to dispose of property while the individual tried to keep these goods for himself or for his immediate offspring; in some cases, officials actually forbade their siblings and family from using the funds allocated for their own funerary service.”

Inheritance and Maintaining Family Power in Ancient Egypt

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: “Finally, sources are most explicit when dealing with strategies undertaken by powerful households to preserve their power bases. 6th Dynasty inscriptions from Akhmim show, for instance, that a high official called Tjeti- Kaihep abandoned a very promising career at the court, in Memphis, and returned to Akhmim in order to replace his (prematurely deceased?) elder brother as chief of the local temple and “great overlord of the nome,” two positions traditionally held by his family and which ensured them a leading role in the province. Apparently, Tjeti-Kaihep preferred to control the traditional, local power-base of his family instead of developing a high- ranking career in the capital. In the case of the Middle Kingdom governor Khnumhotep II of Beni Hassan, his claim to his position was hereditary right and royal favor, and his autobiography illustrates the degree to which power-blocks cemented by marriage alliances could arise, based on the control of some provinces, on positions held at court, and on connections with other powerful families. Other inscriptions show that the position of governor of a city, held for generations within a family, could be sold to a member of the kin-group (hAw) and thus preserved within the extended family. Even at a modest level, buying and selling official positions (such as priestly office) prevented a household from losing control over institutional income and sources of power. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“In fact, the transmission of the household to the next generation was always a delicate affair. The elder son usually inherited a larger share of the family possessions, with the obligation to bury his parents and perform rituals in their honor. However, the family ideology was strong enough to mask other forms of transmission within a set of fictitious kin expressions (e.g., the simultaneous existence of several “elder sons,” pseudo-adoptions, etc.). Significantly, the transfer of permanent legal rights to own and bequeath property was established by means of a document called jmjt-pr (lit. “what is in the house”). In the end, family ideology was a powerful tool that not only ensured the cohesion of the household and preserved its identity, but also provided alternative values to the official ones. Multiple burials, the cult of dead relatives, the display of genealogies and pride of lineage, and economic self-sufficiency figure prominently as its most conspicuous elements.”

See Separate Article: INHERITANCE IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024