Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

WOMEN AS MOTHERS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Dr Joann Fletcher of the University of York wrote for BBC: “But with the 'top job' far more commonly held by a man, the most influential women were his mother, sisters, wives and daughters. Yet, once again, many clearly achieved significant amounts of power as reflected by the scale of monuments set up in their name. Regarded as the fourth pyramid of Giza, the huge tomb complex of Queen Khentkawes (c.2500 B.C.) reflects her status as both the daughter and mother of kings. The royal women of the Middle Kingdom pharaohs were again given sumptuous burials within pyramid complexes, with the gorgeous jewellery of Queen Weret discovered as recently as 1995. [Source: Dr Joann Fletcher, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

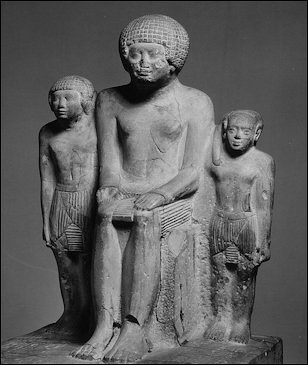

The esteem which the son felt for his mother was so great that in the tombs of the Old Kingdom, the mother of the deceased is as a rule represented there with the wife, while the father rarely appears. On the funerary stelae of later times also, it is the usual custom to trace the descent of the deceased on the mother's side, and not, as we usually do, on that of the father. We read of “Ned'emu-sncb, born of Sat-Hathor; of Anhor, born of Neb-onet, or of Sebekreda, born of Sent," but who were the respective fathers we are not told, or they are only mentioned incidentally. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

“Thou shalt never forget what thy mother has done for thee," teaches the wise 'Eney, “she bare thee and nourished thee in all manner of ways. If thou forgettest her, she might blame thee, she might 'lift up her arms to God, and He would hear her complaint.' After the appointed months she bare thee, she nursed thee for three years. She brought thee up, and when thou didst enter the school, and wast instructed in the writings, she came daily to thy master with bread and beer from her house."

RELATED ARTICLES:

WOMEN IN ANCIENT EGYPT: STATUS, FEMININITY AND IDEAS ABOUT GENDER africame.factsanddetails.com ;

WOMEN'S RIGHTS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: EQUALITY, CONTRACTS, VIOLENCE africame.factsanddetails.com

FAMILIES IN ANCIENT EGYPT: HOUSEHOLDS, PARENTS AND CHILDREN africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MARRIAGE, DIVORCE AND LOVE IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Daughters of Isis: Women of Ancient Egypt” by Joyce Tyldesley (1994) Amazon.com;

“Dancing for Hathor: Women in Ancient Egypt” by Carolyn Graves-Brown (2010) Amazon.com;

“Kinship and Family in Ancient Egypt: Archaeology and Anthropology in Dialogue”

by Leire Olabarria (2020) Amazon.com;

“Households in Context: Dwelling in Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt” by Caitlín Eilís Barrett and Jennifer Carrington (2024) Amazon.com;

“Childhood in Ancient Egypt” by Amandine Marshall and Colin Clement (2022) Amazon.com;

“Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years” by Elizabeth Wayland Barber (1994) Amazon.com;

“The Book of Looms: A History of the Handloom from Ancient Times to the Present” by Eric Broudy (2021) Amazon.com;

“Silent Images: Women in Pharaonic Egypt ” by Zahi Hawass (1995) Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Wives in Ancient Egypt

Dr Joann Fletcher of the University of York wrote for BBC: ““Pharaohs also had a host of 'minor wives' but, since succession did not automatically pass to the eldest son, such women are known to have plotted to assassinate their royal husbands and put their sons on the throne. Given their ability to directly affect the succession, the term 'minor wife' seems infinitely preferable to the archaic term 'concubine'. [Source: Dr Joann Fletcher, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Yet even the word 'wife' can be problematic, since there is no evidence for any kind of legal or religious marriage ceremony in ancient Egypt. As far as it is possible to tell, if a couple wanted to be together, the families would hold a big party, presents would be given and the couple would set up home, the woman becoming a 'lady of the house' and hopefully producing children. |::|

“Whilst most chose partners of a similar background and locality, some royal women came from as far afield as Babylon and were used to seal diplomatic relations. Amenhotep III described the arrival of a Syrian princess and her 317 female attendants as 'a marvel', and even wrote to his vassals-'I am sending you my official to fetch beautiful women, to which I the king will say good. So send very beautiful women-but none with shrill voices'! |::|

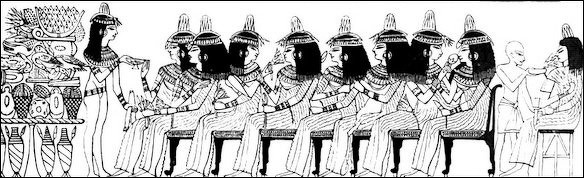

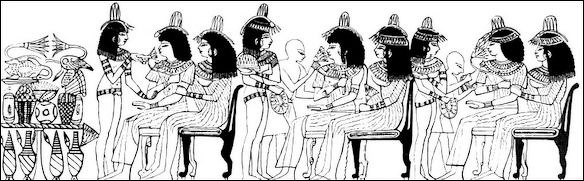

“Such women were given the title 'ornament of the king', chosen for their grace and beauty to entertain with singing and dancing. But far from being closeted away for the king's private amusement, such women were important members of court and took an active part in royal functions, state events and religious ceremonies. |::|

“With the wives and daughters of officials also shown playing the harp and singing to their menfolk, women seem to have received musical training. In one tomb scene of c.2000 B.C. a priest is giving a kind of masterclass in how to play the sistrum (sacred rattle), as temples often employed their own female musical troupe to entertain the gods as part of the daily ritual. |::|

Role of the Wife in Ancient Egypt

The wife helps her husband to superintend the household; she and the children look on while he is netting birds, or she accompanies him in his boating expeditions for sport through the swamps.' The inscriptions of the Old Kingdom praise the wife who is “honoured by her husband," and the old book of wisdom of the governor Ptahhotep, declares him to be wise who “founds for himself a house, and loves his wife." [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

How deeply affectionate a marriage might be is shown by the touching confessions of a widower, which have been preserved to us in a Leyden papyrus of late date. After the death of his wife 'Anch'ere, he fell ill and a magician seems to have told him that it was his wife who sent him this misfortune; he then wrote a sorrowful letter to the “wise spirit “of 'Anch'ere and laid it upon her tomb in the hope of propitiating her.

He complains: “What evil have I done to thee, that I should find myself in this wretched state. What then have I done to thee, that thou shouldcst lay thy hand upon me, when no evil has been done to thee ? From the time when I became thy husband until now — have I done anything which I had to hide from thee? . . . Thou didst become my wife when I was young, and I was with thee. I was appointed to all manner of offices, and I was with thee; I did not forsake thee nor cause thine heart any sorrow. . . . Behold, when I commanded the foot soldiers of Pharaoh together with his chariot force, I did cause thee to come that they might fall down before thee, and they brought all manner of good things to present to thee . . . When thou wast ill with the sickness which afflicted thee, I went to the chief physician, and he made thee thy medicine, he did everything that thou didst say he should do. When I had to accompany Pharaoh on his journey to the south, my thoughts were with thee, and I spent those eight months without caring to eat or to drink. When I returned to Memphis, I besought Pharaoh and betook myself to thee, and I greatly mourned for thee with my people before my house.'

“Ladies of the House” in Ancient Egypt

Dr Joann Fletcher of the University of York wrote for BBC: “The most common female title 'Lady of the House' involved running the home and bearing children, and indeed women of all social classes were defined as wives and mothers first and foremost. Yet freed from the necessity of producing large numbers of offspring as an extra source of labour, wealthier women also had alternative 'career choices'. |[Source: Dr Joann Fletcher, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“After being bathed, depilated and doused in sweet heavy perfumes, queens and commoners alike are portrayed sitting patiently before their hairdressers, although it is equally clear that wigmakers enjoyed a brisk trade. The wealthy also employed manicurists and even female make-up artists, whose title translates literally as 'painter of her mouth'. Yet the most familiar form of cosmetic, also worn by men, was the black eye paint which reduced the glare of the sun, repelled flies and looked rather good. |::|

“Dressing in whatever style of linen garment was fashionable, from the tight-fitting dresses of the Old Kingdom (c.2686-2181 B.C.) to the flowing finery of the New Kingdom (c.1550-1069 B.C.), status was indicated by the fine quality of the linen, whose generally plain appearance could be embellished with coloured panels, ornamental stitching or beadwork. Finishing touches were added with various items of jewellery, from headbands, wig ornaments, earrings, chokers and necklaces to armlets, bracelets, rings, belts and anklets made of gold, semi-precious stones and glazed beads. |::|

“With the wealthy 'lady of the house' swathed in fine linen, bedecked in all manner of jewellery, her face boldly painted and wearing hair which more than likely used to belong to someone else, both male and female servants tended to her daily needs. They also looked after her children, did the cleaning and prepared the food, although interestingly the laundry was generally done by men.” |::|

“Freed from such mundane tasks herself, the woman could enjoy all manner of relaxation, listening to music, eating good food and drinking fine wine. One female party-goer even asked for 'eighteen cups of wine for my insides are as dry as straw'. Women are also portrayed with their pets, playing board games, strolling in carefully tended gardens or touring their estates. Often travelling by river, shorter journeys were also made by carrying-chair or, for greater speed, women are even shown driving their own chariots.” |::|

ladies party

Hatnofer: Portrait of a New Kingdom Housemistress

Catharine H. Roehrig of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Sometime around 1473 B.C., an elderly woman named Hatnofer was laid to rest in the Theban necropolis in a small rock-cut tomb that had been prepared for her by her son Senenmut (31.4.2). Hatnofer had lived through an extraordinary time in Egypt's history. She was born late in the reign of Ahmose in the vicinity of Armant, a town some ten miles south of Thebes. In about 1540 B.C., less than a decade before Hatnofer's birth, Ahmose had reunited the two lands of Egypt by defeating the Hyksos, descendants of migrants from western Asia who had settled in the eastern delta and controlled Lower Egypt and part of the Nile valley to the north of Thebes for about a century. [Source: Catharine H. Roehrig, Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

Identified by historians as the founder of the New Kingdom and the first ruler of Dynasty 18, Ahmose was the brother of Kamose, the last king of Dynasty 17, whose family had ruled Thebes and part of southern Egypt during what we now call the Second Intermediate Period. Since Hatnofer's hometown was part of the Theban province, one or more of her close male relatives almost certainly would have fought alongside these Theban kings in the battles that eventually drove the Hyksos back into western Asia and secured the throne of a united Egypt for Ahmose. \^/

“When we consider that she lived in the middle of the second millennium B.C., Hatnofer was fortunate to have been born into a culture that recognized a woman as an individual, not merely as the possession of her male relatives. In Egypt, a woman could inherit, buy, and sell property in her own right. Any material goods or land that she brought to her marriage remained hers, and she could make a will to distribute her property as she wished. She could take grievances before a judge, be a witness in a court case, and even sit on a jury. Although Egyptian society was essentially patriarchal and men generally held all positions of power, both on the local level and at the royal court, a wife could carry out at least some of her husband's official duties when he was absent. Indeed, during Hatnofer's lifetime, circumstances arose that allowed a woman, Hatshepsut (29.3.2), to claim the most powerful position in the land. \^/

“At the time of her death, Hatnofer was a short, rather stout grandmother of about sixty—a "good old age" in Egyptian terms. Just over five feet tall, with a delicate bone structure, she must have been quite attractive as a young woman. On special occasions, she probably wore her dark brown, naturally curly hair in braids similar to those seen on a statuette of one of her contemporaries (26.7.1404) that is now in the Museum's collection. In order to achieve the volume necessary for this hairstyle, Hatnofer would have augmented her own hair with supplementary braids of the same color. Even after her death, when her mummy was being prepared for burial, scores of dark brown supplementary braids were woven into her white hair in an imitation of the style of her youth. \^/

“Like all Egyptians, men as well as women, Hatnofer would have used various kinds of cosmetics, including oils and unguents to protect her skin from the dryness of the Upper Egyptian climate. She also would have outlined her eyes with kohl, a blue, green, or black powder of ground minerals that was thought to enhance the eyes' beauty while protecting them from the sun's glare. In order to apply her makeup and admire her handiwork, Hatnofer had several mirrors (36.3.69,.13) made of highly polished bronze or silver set into wood or metal handles. She also owned a bronze razor, which was found with other cosmetic implements inside a basket in her tomb (36.3.189,.190,.199). \^/

“Hatnofer probably married before the age of twenty, moving into the household of her husband, Ramose. We know nothing of Ramose's background, but he seems to have been a man of modest means—anything from a tenant farmer to an artisan or even a small landowner. He probably brought his wife into the house of his parents rather than to an establishment that was exclusively his own. Egyptian households often comprised a number of generations, including parents, elderly grandparents, and unmarried and married siblings and their children. Prosperous households would also have included servants. In the early years of her marriage, Hatnofer was probably subordinate to her mother-in-law and may have shared housekeeping duties with her husband's unmarried sisters. Eventually, however, she became the head of her own household and was given the honorific title nebet per, meaning "housemistress."

Three wooden chests containing a total of seventy-six long, fringed sheets of linen (36.3.56,.54,.111) were found in Hatnofer's tomb. Ranging from fourteen to fifty-four feet in length, the sheets had seen much wear, and some had been mended. Before being placed in the chests, the individual pieces of fabric had been laundered, pressed, and carefully folded into neat rectangles. Among the other objects associated with Hatnofer's tomb was a leather tambourine that was found just outside the entrance. Although it may have been used in the funerary ritual performed at her burial, the instrument was probably one of Hatnofer's personal possessions. In ancient Egypt, just as today, music enriched all spheres of life, from the family home to the temples of the gods.” \^/

Female Education and Literacy in Ancient Egypt

Peter A. Piccione wrote: “It is uncertain, generally, how literate the Egyptian woman was in any period. Baines and Eyre suggest very low figures for the percentage of the literate in the Egypt population, i.e., only about 1 percent in the Old Kingdom (i.e., 1 in 20 or 30 males). Other Egyptologists would dispute these estimates, seeing instead an amount at about 5-10 percent of the population. In any event, it is certain that the rate of literacy of Egyptian women was well behind that of men from the Old Kingdom through the Late Period. Lower class women, certainly were illiterate; middle class women and the wives of professional men, perhaps less so. The upper class probably had a higher rate of literate women. [Source: Peter A. Piccione, College of Charleston,“The Status of Women in Ancient Egyptian Society,” 1995, Internet Archive, from NWU -]

“In the Old and Middle Kingdoms, middle and upper class women are occasionally found in the textual and archaeological record with administrative titles that are indicative of a literate ability. In the New Kingdom the frequency at which these titles occur declines significantly, suggesting an erosion in the rate of female literacy at that time (let alone the freedom to engage in an occupation). However, in a small number of tomb representations of the New Kingdom, certain noblewomen are associated with scribal palettes, suggesting a literate ability. Women are also recorded as the senders and recipients of a small number of letters in Egypt (5 out of 353). However, in these cases we cannot be certain that they personally penned or read these letters, rather than employed the services of professional scribes. -

“Many royal princesses at court had private tutors, and most likely, these tutors taught them to read and write. Royal women of the Eighteenth Dynasty probably were regularly trained, since many were functioning leaders. Since royal princesses would have been educated, it then seems likely that the daughters of the royal courtiers were similarly educated. In the inscriptions, we occasionally do find titles of female scribes among the middle class from the Middle Kingdom on, especially after the Twenty-sixth Dynasty, when the rate of literacy increased throughout the country. The only example of a female physician in Egypt occurs in the Old Kingdom. Scribal instruction was a necessary first step toward medical training. -

Women's Occupations in Ancient Egypt

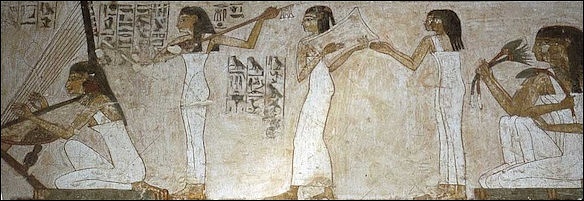

Career options for women were limited. Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times, “Women might find work as professional mourners — one sees a cluster of them gesturing and wailing in a funerary carving — or as performers in court and temple rituals. In a relief from the tomb of a Middle Kingdom queen, female musicians raise frondlike hands in the air as they clap out a rhythm.

musicians

Peter A. Piccione wrote: “In general, the work of the upper and middle class woman was limited to the home and the family. This was not due to an inferior legal status, but was probably a consequence of her customary role as mother and bearer of children, as well as the public role of the Egyptian husbands and sons who functioned as the executors of the mortuary cults of their deceased parents. It was the traditional role of the good son to bury his parents, support their funerary cult, to bring offerings regularly to the tombs, and to recite the offering formula. Because women are not regularly depicted doing this in Egyptian art, they probably did not often assume this role. When a man died without a surviving son to preserve his name and present offerings, then it was his brother who was often depicted in the art doing so. Perhaps because it was the males who were regularly entrusted with this important religious task, that they held the primary position in public life. [Source: Peter A. Piccione, College of Charleston,“The Status of Women in Ancient Egyptian Society,” 1995, Internet Archive, from NWU -]

“As far as occupations go, in the textual sources upper class woman are occasionally described as holding an office, and thus they might have executed real jobs. Clearly, though, this phenomenon was more prevalent in the Old Kingdom than in later periods (perhaps due to the lower population at that time). In Wente's publication of Egyptian letters, he notes that of 353 letters known from Egypt, only 13 provide evidence of women functioning with varying degrees of administrative authority. -

“On of the most exalted administrative titles of any woman who was not a queen was held by a non-royal women named Nebet during the Sixth Dynasty, who was entitled, "Vizier, Judge and Magistrate." She was the wife of the nomarch of Coptos and grandmother of King Pepi I. However, it is possible that the title was merely honorific and granted to her posthumously. Through the length of Egyptian history, we see many titles of women which seem to reflect real administrative authority, including one woman entitled, "Second Prophet (i.e. High Priest) of Amun" at the temple of Karnak, which was, otherwise, a male office. Women could and did hold male administrative positions in Egypt. However, such cases are few, and thus appear to be the exceptions to tradition. Given the relative scarcity of such, they might reflect extraordinary individuals in unusual circumstances. -

“Women functioned as leaders, e.g., kings, dowager queens and regents, even as usurpers of rightful heirs, who were either their step-sons or nephews. We find women as nobility and landed gentry managing both large and small estates, e.g., the lady Tchat who started as overseer of a nomarch's household with a son of middling status; married the nomarch; was elevated, and her son was also raised in status. Women functioned as middle class housekeepers, servants, fieldhands, and all manner of skilled workers inside the household and in estate-workshops. -

“Women could also be national heroines in Egypt. Extraordinary cases include: Queen Ahhotep of the early Eighteenth Dynasty. She was renowned for saving Egypt during the wars of liberation against the Hyksos, and she was praised for rallying the Egyptian troops and crushing rebellion in Upper Egypt at a critical juncture of Egyptian history. In doing so, she received Egypt's highest military decoration at least three times, the Order of the Fly. Queen Hatshepsut, as a ruling king, was actually described as going on military campaign in Nubia. Eyewitness reports actually placed her on the battlefield weighing booty and receiving the homage of defeated rebels. -

Careers for Women in Ancient Egypt

Dr Joann Fletcher of the University of York wrote for BBC: “In fact, other than housewife and mother, the most common 'career' for women was the priesthood, serving male and female deities. The title, 'God's Wife', held by royal women, also brought with it tremendous political power second only to the king, for whom they could even deputise. The royal cult also had its female priestesses, with women acting alongside men in jubilee ceremonies and, as well as earning their livings as professional mourners, they occasionally functioned as funerary priests. [Source: Dr Joann Fletcher, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Their ability to undertake certain tasks would be even further enhanced if they could read and write but, with less than 2 percent of ancient Egyptian society known to be literate, the percentage of women with these skills would be even smaller. Although it is often stated that there is no evidence for any women being able to read or write, some are shown reading documents. Literacy would also be necessary for them to undertake duties which at times included prime minister, overseer, steward and even doctor, with the lady Peseshet predating Elizabeth Garret Anderson by some 4,000 years. |::|

“By Graeco-Roman times women's literacy is relatively common, the mummy of the young woman Hermione inscribed with her profession 'teacher of Greek grammar'. A brilliant linguist herself, Cleopatra VII endowed the Great Library at Alexandria, the intellectual capital of the ancient world where female lecturers are known to have participated alongside their male colleagues. Yet an equality which had existed for millennia was ended by Christianity-the philosopher Hypatia was brutally murdered by monks in 415 AD as a graphic demonstration of their beliefs. |::|

“With the concept that 'a woman's place is in the home' remaining largely unquestioned for the next 1,500 years, the relative freedom of ancient Egyptian women was forgotten. Yet these active, independent individuals had enjoyed a legal equality with men that their sisters in the modern world did not manage until the 20th century, and a financial equality that many have yet to achieve. |::|

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024