Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

MARRIAGE IN ANCIENT EGYPT

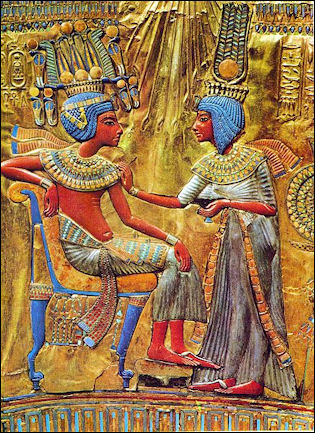

Tutankhamun and his wife Marriage was regarded as alliance between families, a joining of clans and union of property. Couples became married when they decided to live together. There was nor civil or religious ceremony. Prenuptial agreements were routinely signed to protect property.

Some scholars believe that the wedding ring dates back to ancient Egypt. The finger ring was first used by the Egyptians around 2800 B.C. Some scholars believed that it may have symbolized marriage since the Egyptians viewed married as something that lasted an eternity and a circle or ring had no end. Rings of gold were prized by Egyptian nobility.

Egyptian exchanged sandals when they exchanged property or authority. A sandal was given to a groom by the father of the bride. Some believe the word "honeymoon" comes from the ancient Egyptian custom of kidnaping the bride and holding her captive a moon (a month) and drinking a honey-sweetened drink during that time.

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “Marriage and family ties among the common ancient Egyptians were not significantly different then those we see around the world today. The ancient Egyptians held marriage as a sacred bond. This has been made clear in the many statues and writings that depict men and women in a relationship where both depended upon each other. Many myths of the ancient Egyptian marriage practices have been found to be untrue. For a long time many people thought that the Egyptian man would take many wives. This has been proven largely untrue. Some kings would take many wives in order to produce an heir to his throne, however, the common man would take more then one wife only in the event that his wife couldn’t produce a child. Instances of child adoption have been documented in their history. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

Jaana Toivari-Viitala of the University of Helsinki wrote: “Marriage formed a central social construct of ancient Egyptian culture. It provided the normative framework for producing children, who would act as one’s rightful heirs. The latter were responsible for performing one’s funerary cult, thereby securing one’s eternal life. The economic effects of marriage were also notable. The husband, wife, and children were all perceived as having equal rights to the conjugal joint-property consisting of a 1/3 share each. In addition to this, the spouses might own private property of their own. As marriage modified many aspects of daily life such as social status, domicile, and the intricate network of interpersonal rights and obligations, it was not a relationship entered into at random. A sequence consisting of a choice of partner followed by an exchange of gifts and assets preceded the actual marrying. Once the marital status was a fact, both parties were expected to abstain from extramarital relationships. However, it was possible for men to have several wives. [Source: Jaana Toivari-Viitala, University of Helsinki, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“In view of textual evidence dating to the New Kingdom (1548 - 1086 B.C.), marriage may be defined as a contract. Local customs and social status most likely made their mark on the specifics of any actual marriage process. The wedding of a pharaoh was different from that of a poor farmer. Marriage practices appear also to have become somewhat modified as times changed. The material is somewhat vague regarding when one should enter into matrimony (for the first time). The ideal age for the bridegroom was probably when he had established himself in a profession. The bride might have been in her early or late teens. Such age groups feature in texts referring to marriages dating to Late and Ptolemaic and Roman Periods.

“There are numerous studies on ancient Egyptian marriage. Some focus on time period, geographical location, or type of source material. Marriage features also in studies dealing, for example, with ancient Egyptian law, ancient Egyptian women, or kinship, whereby legal and gender studies as well as cultural anthropology respectively provide methodological tools for the analysis. However, trying to match the ancient source material to theoretical and methodological frameworks and rhetoric is not unproblematic. Moreover, as the evidence is limited to a relatively modest number of various types of written references and pictorial material, often with quite specific agendas and spread over some thousands of years, any analysis made is inevitably incomplete.”

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ceremonies of Love Wedding Traditions in Ancient Egypt” by Oriental Publishing (2024) Amazon.com;

“In Bed with the Ancient Egyptians” by Charlotte Booth (2019) Amazon.com;

“Love Poetry and Songs from the Ancient Egyptians” by Gilbert Moore (2015)

Amazon.com;

“Blood Is Thicker Than Water’ – Non-Royal Consanguineous Marriage in Ancient Egypt: An Exploration of Economic and Biological Outcomes” by Joanne-Marie Robinson (2020) Amazon.com;

“An Incestuous and Close-Kin Marriage in Ancient Egypt and Persia: Examination of the Evidence” by Paul John Frandsen (2009) Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Egypt” by Gay Robins (1993) Amazon.com;

“Dancing for Hathor: Women in Ancient Egypt” by Carolyn Graves-Brown (2010) Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Sources on Ancient Egyptian Marriage

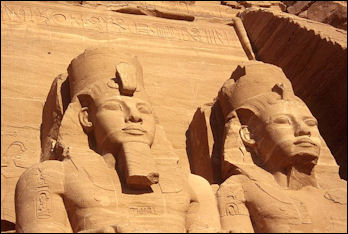

Ramses II and his wife Jaana Toivari-Viitala of the University of Helsinki wrote: “The earliest text references to marriage originate from Old Kingdom (2670 - 2168 B.C.) tomb inscriptions, various types of tomb equipment, and other monuments. The owner of these was usually a male official belonging to the elite of the society. Monuments owned by women are few. In common during Dynasties 4 - 5 (2600 - 2350 B.C.), the woman was usually given a secondary place. Exceptions to this general tendency do exist however. [Source: Jaana Toivari-Viitala, University of Helsinki, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“Evidence of marriage obtained from the Old Kingdom source material consists mainly of titles indicating the marital state (often associated with depictions of the spouses), the word used for wife being Hmt and that for husband hAy. Monuments with this kind of data continue to constitute a notable source of information through Pharaonic history. References to wives outnumber those to husbands. This is to be expected as persons mentioned in tombs were identified through their relationship to the tomb owner, who in most cases was a man. Marking the marital state does not appear to overshadow other titles designating high social rank and functions. References to actual marriages or marrying dating to the Old Kingdom are few.

“Various types of written source material multiply from the Middle Kingdom (2040 - 1640 B.C.) onward as literacy and access to written culture increase, yet references with specific information on the marriage process and divorce remain sparse. Didactic literature, situated in the circle of the elite, contains some references to male ideals of marriage and family. In the Teaching of Ptahhotep one is advised to found a household when one prospers. The wife is to be loved, respected, and provided for while at the same time kept under control. She should not be divorced on light grounds. Similar ideals, with the additional mention of procreating male children, are articulated also in the Instruction of Djedefhor, the Teaching of Ani, which additionally advises not to control an efficient wife but to treat her well, and the Teaching of Onchsheshonqy.

“Other literary texts also contain references to marriage, such as the Story of Sinuhe and the Tale of the Doomed Prince. In both tales, the main character is given a foreign woman as a wife. He also receives ample gifts by his father-in- law. In the story of Naneferkaptah in the Setna sequel, a royal sister-brother marriage, for which the sister moves to live with her brother, takes place. The Setna sequel also presents the wickedness of a woman (Tabubu) desiring marriage. Wicked wives feature also in the Tale of Two Brothers.

“The role of the wife as a child bearer is highlighted in the Dialogue Between a Man and His Ba , where the loss of potential unborn children is presented as more tragic than the death of the wife herself. Whether such views were common in real life cannot be substantiated, but marriage is unequivocally presented as the appropriate setting for sexual interaction. In literary texts, extramarital liaisons were punishable by death. In non-literary texts from Deir el-Medina dating to the New Kingdom, erring individuals of both sexes face less dramatic repercussions. Other sexual offences besides infidelity are mentioned, for example, in threat- formulae and comprise cases of a third party (man or ass) violating or raping a man’s wife/“concubine”, assaulting both husband and wife, or alternatively have one of the spouses assault their offspring.

“Descriptions of the ideal marriage process in the didactic literature agree partly with references to marrying found in other types of written sources from the Old Kingdom onward. The increase in the number of non- literary texts corresponds with a greater amount of more specific references to various aspects of marital life. The New Kingdom Deir el-Medina source material constitutes, for example, one notable corpus where such data are found . The abundant material from the Late Period (664 - 332 B.C.) onward that, in addition to all sorts of informal texts, also comprises standardized deeds such as marriage contracts.”

Marriage Terminology in Ancient Egypt

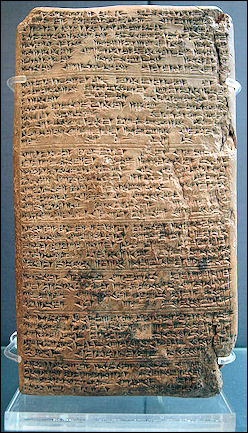

Marriage negotiation between

Egyptian ruler and Hittite ruler

about the latter's daughter Jaana Toivari-Viitala of the University of Helsinki wrote: “Marriage in ancient Egypt was predominantly rendered as a male engineered process expressed by the phrase rdj X Y m Hmt, “to give X to Y as wife,” used from the Old Kingdom onward. The main actor was the father of the woman, as seen, for example, in the 5th Dynasty inscription of the High Priest of Ptah Ptahshepses: [r]dj n=f Hm=f sAt wrt nswt MAat-xa m Hmt=f, “His Majesty gave to him the King’s eldest daughter Maatkha as his wife”. Such a practice is mentioned also in literary texts dating from the Middle and New Kingdom into the Late Period. In the Story of Sinuhe, the verb mnj, “to moor,” is used instead of the verb for “to give” however. [Source: Jaana Toivari-Viitala, University of Helsinki, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“Another frequently used phrase for marrying jrj m Hmt, “to make as a wife,” presents the husband as the agent in the marrying process. In the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.) Papyrus Chester Beatty V , the wording is juxtaposed with the phrase used for bringing up children, “Make for you a wife when you are a youngster and teach her to be a human/woman”. Thus, the man is said to make a woman his wife and additionally educate her into socially recognized adulthood. Marriage constituted a change of status whereby women became wives, men husbands. Additionally, marriage could apparently also function as a mark of adulthood for a woman, whose status of “she being a married woman” (jw=s m Hmt) or “having been a married woman” (wn m Hmt) is often mentioned in the written documentation.

“Men are seldom labeled as husbands, and only in the Late Period does one find occasional references where a woman is the active party “making a husband”. Other titles that could be used as designations for married women were nbt pr, “lady of the house,” st Hmt, “woman,” Hmt TAy, “man’s woman,” snt, “sister,” jryt n Hms/n wnm, “living/eating companion,” rmT, “female person,” Hbswt, “wife(?)/concubine(?), anx(t) n njwt, “citizeness”. The alternative designation used for husband was TAy.

“In addition to status, spatial aspects of marriage were focused on in the terminology employed. Identifying such designations is, however, problematic as independent segments of society with specific sets of specialized terminology did not exist. Thus the phrase “to found a household” (grg pr) appears to have been used to signify both marriage and endowment. To “enter a house” (aq r pr) might designate marrying. It might also refer to literally stepping into a house, cohabiting or having (illicit) sexual intercourse. Other phrases that are challenging to interpret correctly are “to sit/live together”, “(to be) together with” (m-dj), and “to eat together with”.”

Choosing a Marriage Partner in Ancient Egypt

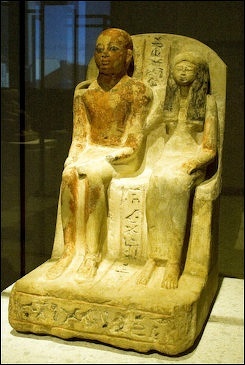

priest and his wife

Jaana Toivari-Viitala wrote:“References to marriage in various literary texts seem to advocate unions between social equals. However, in the story of The Doomed Prince the main character, disguised as a chariot warrior’s son, manages to be given another prince’s daughter as wife before his true noble birth is revealed (The Doomed Prince 6,16). In this case, the young man is said to have personal qualities that make up for the lack of the right social background. In real life, personal social upward mobility through marriage did occur both among the elite and common people. Occasionally even slaves could be freed and adopted and subsequently married into their previous owners’ families . That a spouse was of foreign origin was not entirely unheard of either. The Egyptian royal families used marriage alliances as part of their international diplomatic strategies. [Source: Jaana Toivari-Viitala, University of Helsinki, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“As monuments of various types belong mostly to the royal family and the elite, persons mentioned on these are more or less of equal social background (excluding occasionally featured servants). Middle Kingdom inscriptions convey that some marriages were contracted between elite families from neighboring areas rather than between families from one and the same location. Thus, a marriage union could be used as a means to form alliances and networks on various levels of society, in a similar way the royal family tied marital bonds in order to reach political and diplomatic ends.

“The source material pertaining to the New Kingdom royal tomb-builders’ community at Deir el-Medina indicates that marriages in the village were contracted mainly between locals, although there are some cases where a spouse is attested as coming from elsewhere. Many of the couples in the village shared a background of equal social rank. Moreover, existing kinship ties can be attested between a few of the spouses. It is mostly first cousins who were married to each other, but there might also be a couple of cases where a paternal uncle married his niece and a case where a man might have been married to his maternal aunt. One of the couples at Deir el-Medina appears to have been brother and sister. The references are, however, too few to substantiate statistical estimates regarding partner choice at Deir el-Medina.

“In the 5th Dynasty biography of Ptahshepses, pharaoh chooses Ptahshepses as the husband for his daughter “because His Majesty desired that she be with him more than with any other”. Although a number of marriages appear to have been arranged, emotional attachment could have played a part in the choice of partner. Many epithets featuring in inscriptions contain some form of the verb “to love,” indicating that a person is beloved of, for example, a god, the king, or an official. That is, mostly of someone of higher rank. Bestowing love on one’s inferiors was considered a good deed. As the most common designation for a married woman mentioned in various monuments was “his beloved wife,” marriage was most likely perceived as encompassing love, albeit between two spouses who possibly were not of an entirely equal status. The love and longing articulated in love songs composed during the New Kingdom, on the other hand, are male constructs with little focus on marriage.”

Incestuous Marriage in Ancient Egypt

Among pharaohs and their queens, brothers and sisters and even fathers and daughters intermarried. Incest was a way of keeping property in the family because women could inherent property. Scholars debate whether these marriages were consummated or simply ceremonial.

Describing the implications of a father-daughter marriage, Reay Tannahill wrote in “Sex in History”: "A resulting son would be a half brother of his mother, his grandmother's stepson, his mother's brothers half brother, and not only his father's child but his grandson as well! Note the problems of identity and exercise of authority: should he act toward his mother as a son or as a half-brother; should the uncle be related as an uncle or as a half-brother”...if a brother and sister were to marry then divorce, could they readily revert to their original relationship?"

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “Instances of incest were once thought to be commonplace in ancient Egypt. This has been proven false with the discovery of the semantics of the Egyptian language. When the scholars were first deciphering the hieroglyphs they ran into many references of women and men referring to their spouse as their “brother” or "sister." The terms Brother and Sister reflected the feelings that two people shared, not the heriditary kinship relationship. “My brother torments my heart with his voice, he makes sickness take hold of me; he is neighbor to my mother’s house, and I cannot go to him! Brother, I am promised to you by the Gold of Women! Come to me that I may see your beauty.” [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

See Separate Article: INCEST AND MARRIAGE IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Parties Involved in the Marriage Process

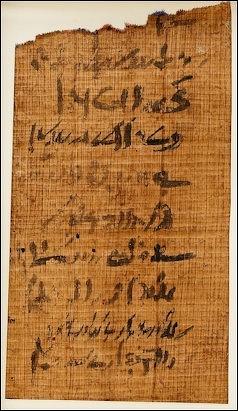

marriage contract

Jaana Toivari-Viitala wrote: “Evidence regarding parties involved in the marriage process is sparse. In references where a woman is said to be given as a wife, the key agent is the woman’s father. One may, however, suggest that the whole household took part in the event, as probably did the family of the groom also. There are occasional references in non-literary texts dating to the New Kingdom where one finds, for example, one groom interacting with a maternal uncle of the bride, another with his bride’s adoptive mother. One might also turn to goddesses, such as Hathor, and ask for help in getting a wife. [Source: Jaana Toivari-Viitala, University of Helsinki, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“The role of the family in the marriage process becomes more visible in the Late Period (712–332 B.C.). Moreover, a change of practice occurs from the 26th Dynasty onward, when some marriage contracts register the phrase “I have taken you as a wife” whereby emphasis shifts from the father of the bride to the groom, who now addresses his bride directly. Non-literary texts do not portray the bride as an active part in the process before the Late Period, but from then on statements such as “you have taken me as your wife” are occasionally recorded. However, already in earlier periods, in literary texts such as The Doomed Prince and the story of Naneferkaptah in the Setna sequel, the girls are active in order to get their ways regarding partner choice.

“Marriage embodied legal, economic, and social rights and obligations, which affected social networks in a community. Thus, also a larger group of friends and neighbors must have taken some interest and involved themselves on some level in marriage arrangements. Regarding the royal family, several officials were probably needed for the practical arrangements.”

Marriage Formalities in Ancient Egypt

Jaana Toivari-Viitala wrote: “Bringing a marriage about firstly requires choice of partner, which involves negotiations and agreements. In most cultures exchanges of various goods and assets generally referred to as bridewealth and dowry then follow. The term grg pr, “to found a house(hold),” was used as a label for gifts given by parents when their children got married. The phrase fAy gAyt, “carrying of a bundle,” found in a few texts from the New Kingdom, a time period when the culture was still predominantly oral, designates goods and services provided by the groom to the bride’s family. After carrying the bundle, the “making of a wife” is said to have taken place. A local court case documented at Deir el-Medina deals with a third party’s sexual involvement with a married woman. This is reported as a crime since the two above mentioned actions had been duly performed. Thus, a violation against a socially acknowledged binding agreement (or contract) could be reported to the local court, a more formal environment than that of direct interpersonal problem solving. [Source: Jaana Toivari-Viitala, University of Helsinki, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“Formal measures to safeguard a daughter’s position in the marriage regarding property rights, divorce, and ill treatment could also be undertaken. The husband might be made to swear oaths, such as the ones recorded in Ostracon Bodleian Library 253 and Ostracon Varille 30, which contained notable penalty clauses if the given promises were broken. Also so-called jmt-pr documents relating to property disposition could be drawn up. In the Late Period, the types of documents made in association with marriage multiply and become more standardized . The most common of these are the Demotic sX n sanx annuity contracts made by the husband to his wife and sXw n Hmt documents guaranteeing the wife’s right to the marital property.”

Marriage and Inheritance

Akhenathon and Nefertiti

Sandra Lippert of Universität Tübingen wrote: “Benefits for the spouse: The division of matrimonial property between the spouses with one third belonging to the wife—first attested in the 17th Dynasty, attested several times in the New Kingdom, and commonly mentioned in Late Period and Ptolemaic marriage documents—has often been seen as a matter of inheritance. In reality, however, the wife did not inherit a third of her husband’s property. Rather, she was endowed with it already during her husband’s lifetime, as can be seen from the fact that the third also fell to her in the case of divorce. Since the attestation of the one-third/two-thirds division far predates the earliest marriage documents and is there given as a well-known fact, it can be safely assumed that it was not dependent upon individual arrangements but legally binding from at least the New Kingdom onwards, as is also suggested by the peculiar phrasing of O. DeM 764, in which this division is set up as a general rule with the typical conditional protasis and injunctive or future apodosis structure of later law texts: “If the children are small, the property will constitute three parts: one for the children, one for the man, one for the woman. If he (i.e., the man) provides for the children, give to him the two thirds of all property, the one third being for the woman”. In Late and Ptolemaic and Roman Period marriage documents, the wife could be allotted to inherit larger parts or even all of her husband’s property, but her right of disposal was usually restricted so that the property would after her death fall automatically to the children. [Source: Sandra Lippert, Universität Tübingen, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Benefits for the children: “As seen above, some jmt-pr documents of the Middle and New Kingdoms, and some marriage documents of the Late and Ptolemaic and Roman Periods through which inheritance was allotted to a wife, state that all property is ultimately to fall to the children. In certain types of marriage documents that became current from the 26th/27th Dynasties onwards, the inheritance rights of the children from the marriage in question were established, sometimes even before the children were born. Often it was stressed that the firstborn son of this marriage would be counted as “eldest son” in the sense of the legal order of succession and therefore be the main or even sole heir: the phrasing “Your eldest son is my eldest son [among the children you will bear to me] . . .” was often extended to “. . . the master of all that I possess and will acquire.” In other documents of this type, all children (or occasionally only the sons) were instituted as heirs of the paternal property. If a man who had made a marriage settlement of the above-mentioned kind married a second time (either because he had divorced his first wife or because she had died), he could only draw up another marriage settlement if the first wife and/or his eldest son agreed to it in writing because he had already pledged his property as security for the maintenance of his first wife and promised it as inheritance to the wife and/or the children from his first marriage. This is explicitly stated in a law cited by the judges of the so-called Siut trial.”

Divorce in Ancient Egypt

George P. Monger wrote in “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ In ancient Egypt, divorce, or the breakdown of the marriage partnership, was a recognized possibility, though to be discouraged — not for religious reasons, but to promote a stable society and a property and inheritance infrastructure. A heavy fine could be imposed on a man for divorcing his wife. The woman had to leave the family home, whether or not she instigated the divorce, making her and her children homeless and placing a burden on the wider society, which took pride in the collective care given to widows, divorced women, and children. Although there were clauses in the marriage contract to provide financial compensation upon divorce, such settlements were not particularly generous and would still leave the woman facing economic problems. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “by George P. Monger, 2004 ^]

Divorce simply involved moving out, after which the man and woman were allowed to remarry. Jaana Toivari-Viitala wrote: “A marriage came to its end with the demise of one of the spouses or due to reasons such as infertility, other physical defects, unfaithfulness, or lack of love. Although social norms appear to have encouraged married couples to stay together, divorces and re-marriages were quite common. [Source: Jaana Toivari-Viitala, University of Helsinki, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“The husband was often the instigator of a divorce. Most of the women did not have a professional career, so their economically and socially weaker position probably encouraged them to try to keep a marriage together at some length. The phrase designating divorce xAa (r bnr), “to throw (out),” was used by men. It reflects the living arrangements by the termination of a marriage. The woman had to leave the conjugal home. There are some indications that she additionally also had to leave the children with the husband. When a woman is said to end a marriage, the word Sm, “to go (away),” was used.

“In New Kingdom sources, one finds cases where divorce is referred to with the verb arq, “to swear.” The location for this event was the local court. A text listing divorces, Ostracon A. Gardiner 19, and some other documents recording property settlements made in connection with divorces indicate that ending a marriage indeed required some formal proceedings.

“Moreover, there is a general rule regarding property rights recorded on an ostracon, Ostracon DeM 764, where the wife is said to have a right to 1/3 of the property while 1/3 was for the husband and 1/3 for the children. As the children stayed with the father, he was left in charge of the children’s portion also. It would appear that the term sfr, previously interpreted as dowry , could be used for the aforementioned 1/3 of conjugal joint- property allotted to the woman.

“A divorced woman lost her status as wife. She became an “ex-wife” (Hmt HAty), yet she retained her status as mother of her children. She might seek lodgings at her parent’s or brother’s place. Other relatives or her in- laws might also provide her with shelter. In this respect, the situation of a divorced woman could resemble that of a widow with little property. There seems to have been a strong tendency for both men and women to remarry. A second marriage was not alwaysfree of complications for the women, however. In the Late Period temple oaths, ex- husbands are made to swear that they will leave their ex-wives in peace. Thus, cases where jealous ex-husbands harassed their former wives probably existed.”

Social, Economic, and Legal Implications of Marriage and Divorce

Jaana Toivari-Viitala wrote: “Marriage functioned as the prescribed social construct for the procreation of offspring. The children secured one’s eternal life by sustaining one’s funerary cult. They were one’s rightful heirs, who continued the family line on earth. Thus, marriage could be described as cohabitation with intent to reproduce. Ideally the cohabitation came about by the spouses setting up a home of their own. They might alternatively move in with the parents of either party. In addition to being a spatially visible construct and marking social status, marriage also caused notable rearrangements in wider and intricate social networks entailing interpersonal rights and obligations. [Source: Jaana Toivari-Viitala, University of Helsinki, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“One great concern, often apparently requiring written documentation from the Old Kingdom onward, was title to property. In addition to references where husbands and wives pass on property to their offspring, husbands sometimes bequeathed property (or right to income) to their wives. These texts do not specify rights to the matrimonial joint property, as is done in the guideline recorded in O. DeM 764, mentioned previously. The latter document highlights the children’s importance, irrespective of gender, as additional holders of rights to the conjugal joint property alongside their parents. Although joint property was part of the marriage construct, the spouses could own private property also. This is seen clearly in documents dating from the Late Period onward. In addition to existing family ties, providing for a deceased’s funeral could provide the right to inherit such property.

“Material dating to the Late Period also contains more specific information on intra- familial dynamics in relation to various types of rights and obligations. One concept featuring in these sources is, for example, the “right to a wife”, which may refer to the man’s exclusive sexual right to his wife. The term is not attested from earlier periods. “On the whole it seems safe to assume that the families as well as the community at large during all periods of Pharaonic history probably exercised some control in order to have expectations associated with marital life followed. It is, moreover, possible that there were diverse types of normatively accepted liaisons or “marriages” embedded in the intricate social texture.”

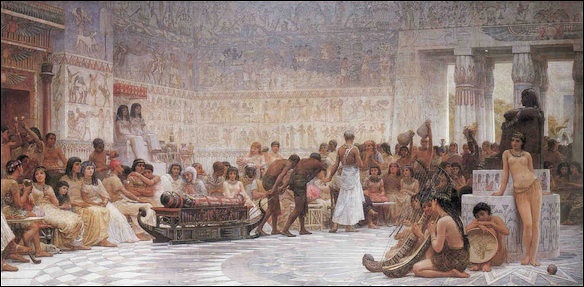

an Egyptian feast by Edwin Long

Harems in Ancient Egypt

Silke Roth of Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Germany wrote: “In Egyptological research, the term “harem” (harim) comprises a conglomerate of phenomena, which can be distinguished as: 1) the community of women and children who belonged to the royalhousehold; 2) related institutions, including administrative organizations and personnel; and associated localities and places, like palaces and royal apartments, as well as agricultural land and manufacturing workshops. Key functions of this so-called royal harem can be identified as the residence and stage for the court of the royal women, the place for the upbringing and education of the royal children and favored non-royal children as the future ruling class, the provision of musical performance in courtly life and cult, as well as the supply and provisioning of the royal family. Related Egyptian terms include ipet (from Dynasty 1 onwards), khenere(t) (from the Old Kingdom), and per kheneret (New Kingdom). The compounds ipet nesut and kheneret (en) nesut, commonly “royal harem,” are attested as early as the Old Kingdom. Only a few sources testify to the existence of the royal harem after the 20th Dynasty. [Source: Silke Roth, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“In ancient Egypt, polygamy was basically restricted to the ruler and his family. Therefore, it is only possible to speak of a “harem” for the royal women and their social circle as well as the related institutions and localities. Given the primary meaning of the harem in the oriental-Islamic cultural spheres and especially the Ottoman example, however, the associated terminology is only limitedly applicable to the so-called harem of the Egyptian king. Nevertheless, both Ottoman and Egyptian harems were centrally involved in raising and educating the future ruler and, more generally, the future inner elite group.

The term “harem” generally describes a cultural phenomenon that is primarily known from oriental-Islamic cultural spheres, where it is still attested. It denotes a very protected part of the house or palace sphere in which the female family members and younger children of a ruler/potentate as well as their servants live separated from the public (Turkish haram from Arabic Harâm, “forbidden,” “inviolable”).

See Separate Article: HAREMS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024