Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

WOMEN IN ANCIENT EGYPT

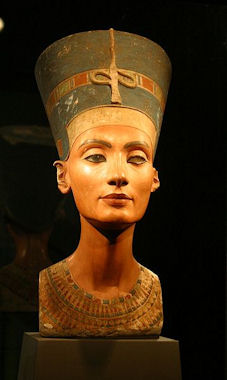

Nefertiti bust Women had relatively high status in ancient Egypt and had more rights that women in other ancient societies. Several women became pharaohs and built their elaborate tombs. "Women could own land, appear before courts as plaintiffs or defendants, serve as priestesses and engage in business dealings." The fact that sculptures of couples presented men and women of equal height was seen as an indication that women enjoyed status equal to that of men.

Women were allowed to travel freely and often enjoyed the same pastimes as men. During important proceeding high raking women sometimes donned fake beards to show they commanded the same authority as men.

The first known book of manners and correct manners, The Instructions of Ptahhotep , written around 2500 B.C. advises women to "Be silent it is a better gift than flowers." In 1850 B.C. women used a tampon-like device made from shredded linen and crushed and gum arabic (acacia branch powder).

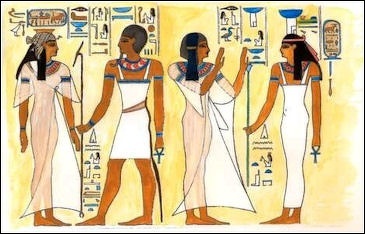

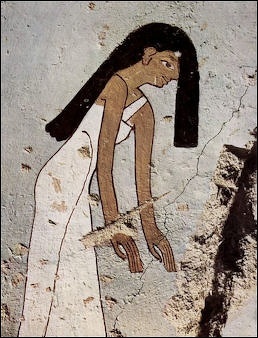

Painting scenes show ancient Egyptian women carrying supplies and food on their head much as some modern Egyptian village women do today. Herodotus wrote how Egyptian women spent a great deal of time laboriously washing linen clothes.

RELATED ARTICLES:

WOMEN'S ROLES IN ANCIENT EGYPT: MOTHERS, WIVES, WORKERS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

WOMEN'S RIGHTS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: EQUALITY, CONTRACTS, VIOLENCE africame.factsanddetails.com

FAMILIES IN ANCIENT EGYPT: HOUSEHOLDS, PARENTS AND CHILDREN africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MARRIAGE, DIVORCE AND LOVE IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Women in Ancient Egypt” by Gay Robins (1993) Amazon.com;

“Dancing for Hathor: Women in Ancient Egypt” by Carolyn Graves-Brown (2010) Amazon.com;

“Daughters of Isis: Women of Ancient Egypt” by Joyce Tyldesley (1994) Amazon.com;

Women in Ancient Egypt: Revisiting Power, Agency, and Autonomy

by Mariam F. Ayad (2022) Amazon.com;

“Women In Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Watterson (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Royal Women of Amarna: Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt" (1996) Amazon.com;

“Women, Gender and Identity in Third Intermediate Period Egypt: The Theban Case Study” by Jean Li (2017) Amazon.com;

“When Women Ruled the World: Six Queens of Egypt” by Kara Cooney (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Cleopatras: Discover the Powerful Story of the Seven Queens of Ancient Egypt!” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (2024) Amazon.com;

”Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh” by Joyce A. Tyldesley (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Woman Who Would Be King” by Kara Cooney (2014) Amazon.com;

“Hatchepsut: The Life of the Female Pharaoh (1507 - 1458 BCE 18th Dynasty)”

by Ron Schaefer Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Women Reflected in Ancient Egyptian Art

Two exhibits of Egyptian art in New York in 1997 — ''Queen Nefertiti and the Royal Women'' at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and ''Mistress of the House, Mistress of Heaven: Women in Ancient Egypt'' at the Brooklyn Museum of Art — highlighted the place that women held in ancient Egypt. Art critic Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times that ''Women in Ancient Egypt'' did a particularly fine job giving viewers an idea of what it was like to be a woman in ancient Egypt. The exhibit he wrote “steers a smooth course between an outdated view of the Egyptian woman as a kind of dynastic fashion plate and a newer theoretical take that threatens to reduce her to a mere pawn in a patriarchal game. Instead, the more than 200 objects gathered here — many of them beautiful, some of them prosaic, a few simply bizarre — confirm the complexity of her identity: as both mistress and servant, mother and mother-goddess, marital commodity and property owner, and as an individual seeking fulfillment in this life and salvation in the next. [Source: Holland Cotter, New York Times, February 21, 1997 ~]

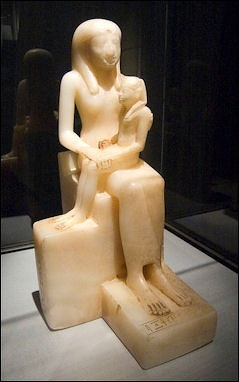

“The show...opens with an Old Kingdom limestone effigy of a man and a woman standing together. Their torsos are sensually modeled, their facial features regular but individualized, melding the ideal with the real. Their pose is unabashedly affectionate: her arm encircles his waist, his hand passes over her shoulder and touches her breast. But distinctions between the figures are marked. The man, in every way the dominant figure, is a full head taller than his mate. Where his face is upward-looking and warmed by a faint but self-confident smile, hers seems pensive. She gazes slightly downward and to the side, tensed, as if listening for something. What could it be? The cry of unruly children? The clatter of plates in a kitchen? The hum of weaving in a distant room? The pulse of life beating in the earth? ~

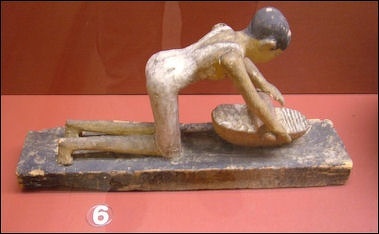

Queen Bint-Anath

“Much about the woman's status can be read here. Variations in the heights of figures are often a visual code for rank in the social hierarchy. While the man in this case is identified by name in an inscription, the woman is not. And contemporary documents suggest that if this pair were married (there is no clear proof that they are), the woman would have fewer legal rights than her husband. In fact, ''Women in Ancient Egypt,'' organized by Glenn Markoe, Anne Capel and Richard Fazzini, does much to upset the long-held assumption that Egyptian society was exceptional among ancient cultures for its sexual parity. Recurrent images in the show of women breast-feeding children, picking fruit, grinding grain, carrying baskets and dressing one another's hair confirm that while men moved in a public sphere, women of all classes were traditionally restricted to the home.” ~

“Some goddesses routinely took human form, as in the case of Maat, an embodiment of natural harmony, who is seen as a small bronze figure perched, with her knees drawn up, on an altar. Others were depicted as half-animal: Hathor had the head of a cow; Sekhmet, both revered and feared for her mercurial disposition, that of a lion. The popular Taweret was a one-person menagerie, with the head of a hippopotamus, the body of a crocodile, the paws of a lion, human breasts and a million-watt grin guaranteed to scare off ill-intentioned spirits.

“These composite deities, in whom the fantastic and the everyday effortlessly merge, are among the unforgettable creations of world art. Yet the images in the show that linger longest in the mind are those that feel most intimately human. It would be hard to find a vision more tender than that in the relief carving of Queen Nefertiti kissing her young daughter, their lips meeting as a disembodied celestial hand offers an ankh, the emblem of life. Nor is there anything in the Metropolitan's Nefertiti show to surpass the colossal head of a young queen, carved in dark gray-green chlorite, on view here. This breathtaking fragment, probably once attached to a sphinx's body, made its way to Italy in antiquity and was found at Hadrian's villa near Rome. The young woman's nose is missing, her chin chipped and repaired, but even in ruined condition her wide-eyed, candid visage, with its broad mouth and skin buffed to a soft sheen, palpitates with life.

Status of Women in Egyptian Society

Peter A. Piccione of the College of Charleston wrote in “The Status of Women in Ancient Egyptian Society”: “Unlike the position of women in most other ancient civilizations, including that of Greece, the Egyptian woman seems to have enjoyed the same legal and economic rights as the Egyptian man — at least in theory. This notion is reflected in Egyptian art and historical inscriptions. [Source: Peter A. Piccione, College of Charleston,“The Status of Women in Ancient Egyptian Society,” 1995, Internet Archive, from NWU -]

Queen Ankhnesmeryre II and son

“It is uncertain why these rights existed for the woman in Egypt but no where else in the ancient world. It may well be that such rights were ultimately related to the theoretical role of the king in Egyptian society. If the pharaoh was the personification of Egypt, and he represented the corporate personality of the Egyptian state, then men and women might not have been seen in their familiar relationships, but rather, only in regard to this royal center of society. Since Egyptian national identity would have derived from all people sharing a common relationship with the king, then in this relationship, which all men and women shared equally, they were--in a sense--equal to each other. This is not to say that Egypt was an egalitarian society. It was not. Legal distinctions in Egypt were apparently based much more upon differences in the social classes, rather than differences in gender. Rights and privileges were not uniform from one class to another, but within the given classes, it seems that equal economic and legal rights were, for the most part, accorded to both men and women. -

“Most of the textual and archaeological evidence for the role of women that survives from prior to the New Kingdom pertains to the elite, not the common folk. At this time, it is the elite, for the most part, who leave written records or who can afford tombs that contain such records. However, from the New Kingdom onward, and certainly by the Ptolemaic Period, such evidence pertains more and more to the non-elite, i.e., to women of the middle and lower classes. Actually, the bulk of the evidence for the economic freedom of Egyptian women derives from the Ptolemaic Period. The Greek domination of Egypt, which began with the conquest of Alexander the Great in 332 B.C., did not sweep away Egyptian social and political institutions. Both Egyptian and Greek systems of law and social traditions existed side-by-side in Egypt at that time. Greeks functioned within their system and Egyptians within theirs. Mixed parties of Greeks and Egyptians making contractual agreements or who were forced into court over legal disputes would choose which of the two legal systems in which they would base their settlements. Ironically, while the Egyptians were the subjugated people of their Greek rulers, Egyptian women, operating under the Egyptian system, had more privileges and civil rights than the Greek women living in the same society, but who functioned under the more restrictive Greek social and legal system. -

“The position of women in Egyptian society was unique in the ancient world. The Egyptian female enjoyed much of the same legal and economic rights as the Egyptian male--within the same social class. However, how their legal freedoms related to their status as defined by custom and folk tradition is more difficult to ascertain. In general, social position in Egypt was based, not on gender, but on social rank. On the other hand, the ability to move through the social classes did exist for the Egyptians. Ideally, the same would have been true for women. However, one private letter of the New Kingdom from a husband to his wife shows us that while a man could take his wife with him, as he moved up in rank, it would not have been unusual for such a man to divorce her and take a new wife more in keeping with his new and higher social status. Still, self-made women certainly did exist in Egypt, and there are cases of women growing rich on their own resources through land speculation and the like. -

Powerful Women in Ancient Egypt

Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times that while the options of ordinary women were limited women of high rank could acquire material wealth in the form of real estate and luxury items. A wealth of jewelry survives from burials, and samples in the show range from necklaces of amethyst, gold and lapis lazuli to razor-thin silver torques, and from amulets in the form of shells or animals to effigies of protective goddesses. [Source: Holland Cotter, New York Times, February 21, 1997 ~]

“And a few individuals assumed the role of female pharaohs. The most famous of these was Hatshepsut, builder of a vast mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri. In a large pink granite portrait statue in the show she wears the accouterments of a male king — a false beard, a short kilt — but an inscription refers to her as the daughter of the sun god. Hatshepsut's unorthodox rise to power apparently caused few qualms among her subjects — her reign from 1486 to 1468 B.C. was a time of marked prosperity for Egypt — in part, perhaps, because female deities had long populated the Egyptian pantheon and were familiar presences in its art.” ~

Dr Joann Fletcher of the University of York wrote for BBC: “During Egypt's 'Golden Age', (the New Kingdom, c.1550-1069 B.C.), a whole series of such women are attested, beginning with Ahhotep whose bravery was rewarded with full military honours. Later, the incomparable Queen Tiy rose from her provincial beginnings as a commoner to become 'great royal wife' of Amenhotep III (1390-1352 B.C.), even conducting her own diplomatic correspondence with neighbouring states. |::| [Source: Dr Joann Fletcher, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“The status and privileges enjoyed by the wealthy were a direct result of their relationship with the king, and their own abilities helping to administer the country. Although the vast majority of such officials were men, women did sometimes hold high office. As 'Controller of the Affairs of the Kiltwearers', Queen Hetepheres II ran the civil service and, as well as overseers, governors and judges, two women even achieved the rank of vizier (prime minister). This was the highest administrative title below that of pharaoh, which they also managed on no fewer than six occasions.

“Egypt's first female king was the shadowy Neithikret (c.2148-44 B.C.), remembered in later times as 'the bravest and most beautiful woman of her time'. The next woman to rule as king was Sobeknefru (c.1787-1783 B.C.) who was portrayed wearing the royal headcloth and kilt over her otherwise female dress. A similar pattern emerged some three centuries later when one of Egypt's most famous pharaohs, Hatshepsut, again assumes traditional kingly regalia. During her fifteen year reign (c.1473-1458 B.C.) she mounted at least one military campaign and initiated a number of impressive building projects, including her superb funerary temple at Deir el-Bahari. |::|

“But whilst Hatshepsut's credentials as the daughter of a king are well attested, the origins of the fourth female pharaoh remain highly controversial. Yet there is far more to the famous Nefertiti than her dewy-eyed portrait bust. Actively involved in her husband Akhenaten's restructuring policies, she is shown wearing kingly regalia, executing foreign prisoners and, as some Egyptologists believe, ruling independently as king following the death of her husband c.1336 B.C. Following the death of her husband Seti II in 1194 B.C., Tawosret took the throne for herself and, over a thousand years later, the last of Egypt's female pharaohs, the great Cleopatra VII, restored Egypt's fortunes until her eventual suicide in 30 B.C. marks the notional end of ancient Egypt. |::|

Gender Categories in Ancient Egypt

Queen Hatshephut as a sphinx Deborah Sweeney of Tel Aviv University wrote: “Egyptian gender categories seem rigid, particularly in the realm of representation, where numerous cultural conventions of skin color, hairstyle, body build, clothing, and which body parts may be exposed are used to differentiate between genders, social standing, and ethnic origin. Men are normally represented with darker skin than that of women and hairstyles different from those of women; elite males are characteristically represented in a more active pose than elite women, and equipped with the staff of authority, which is not associated with women; the genitals of elite males are always hidden, although the pubic triangle of elite women is often outlined under their clothing. For a detailed survey of the symbolic representation of men’s and women’s bodies in Egyptian art, see Müller. Moers stresses the social power of the representations of the normative, elegant, well-ordered body in visual and written media: feelings of shame are attributed to people when they fail to conform to this image, such as the young woman in the love poems who worries that “people” will describe her as “one fallen through love” because, distracted by daydreams of her beloved, her heart beats violently and she is neglecting her appearance. Moers also makes the interesting argument that this socially constructed normative body is male: women would always be considered slightly at a disadvantage. [Source: Deborah Sweeney, Tel Aviv University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“However, gender categories may have been more flexible in reality. Texts represent people acting in ways that two-dimensional art omit, partly because formal two-dimensional art is often harnessed to magical ends and tends to prioritize the persons, images, and activities most important to achieve those ends: to please the gods (in temples) and to enable the tomb owner to enter the afterlife and thrive there (in tombs). For instance, elite women’s business activities are known from texts but seldom represented in tombs. Similarly, although the grand majority of cultic singers during the New Kingdom were female, some male ones are known, and although almost all bureaucrats were men, there are occasional examples of female scribes and administrators, and some women helped their husbands unofficially.

“Occasionally the Egyptians themselves remarked that certain behavior was gender inappropriate—“Did women ever lead troops?’”—or highlighted ambigendrous behavior, such as that of the goddess Anat, who is described as “a mighty goddess, a woman acting as a man/a warrior, clad as men, girt like women”.”

Gender Concepts Expressed in Ancient Egyptian Material Culture

Deborah Sweeney of Tel Aviv University wrote: “Gender is often expressed via, and simultaneously shaped by, material culture. Smith’s study of ethnicity in Nubia (2003) is an excellent example, because the way ethnicity is played out in material culture often involves gender- associated artifacts. From the presence of Nubian domestic cookpots and Nubian fertility figurines in household shrines at the fortress of Askut, both of which tended to be associated with women in Egyptian culture, Smith suggests that during the Second Intermediate Period the Egyptians living in the fortresses were marrying local women, who maintained their ethnic identity, among other things, via Nubian foodways. On the other hand, the (male) commander of the fortress, who would have entertained (male) emissaries sent by the ruler of Kerma and other Nubian dignitaries, used elegant Nubian serving vessels to honor his guests, so that interpretive issues pertaining to ceramics, gender, and ethnicity intersected differently in different social settings. [Source: Deborah Sweeney, Tel Aviv University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

female figure from the Neolithic Naqada culture

“Places where certain people might be admitted and others not, or where certain people would find it easier to go than others, also shaped various aspects of identity in ancient Egypt, such as status, membership in or exclusion from a given group, and sometimes gender. Domestic space, shared by both sexes on relatively equal terms of status, may have been particularly important for the expression and shaping of gender. Meskell argues that in the tomb-builders’ village of Deir el-Medina, the first room of the house, often equipped with a domestic altar, was associated with a domestic cult strongly associated with fertility and female themes, whereas the more imposing second room with divan and emplacements for stelae was associated with male activities, including socializing on the weekends. Meskell’s views have been somewhat simplified elsewhere, and it is important to retain her original nuances: the second room was also used by women, particularly during the week when the men were away at work; men could also have participated in cultic activities in the first room; and the first room could also have been used for everyday activities such as spinning or food preparation. On the other hand, Kleinke has argued convincingly that use of the rooms cannot have been restricted to one sex or the other and points out that the domestic ancestor cult and fertility were concerns of both sexes. Similarly, Koltsida makes an excellent case for the use, by both men and women, of the second room in Deir el- Medina houses. We could thus envisage domestic spaces and areas that were associated more with one sex but did not exclude the other, or were the focus of special activities by one sex but where other activities by both sexes also took place.

“Both women and men underwent the same journey through the afterworld and the same judgement at the end, and people were integrated into the community of Osiris regardless of gender. However, McCarthy and Cooney point out that certain aspects of the entrance to the afterlife, such as having intercourse with the Goddess of the West in order to be reborn from her in the next world, required the dead person to be male. Lacking a penis, women might have had difficulty with this aspect of regeneration. McCarthy suggests that Queen Nefertari is represented in her tomb undergoing a fragmentation of her gender identity at death, which allowed her to be identified with Osiris and Ra in order to be regenerated.

“Similar arguments are made by Cooney for women in general in the New Kingdom. Cooney demonstrates how this redefinition of women’s gender on entering the afterlife was reflected in the gender- neutral or masculine representation of women in certain kinds of burial equipment, such as (most) shabtis and coffins. Once she had successfully passed the judgement of the dead, a woman would attain the status of akh (glorified spirit), and would thus be depicted as a woman, adoring the gods of the afterworld and enjoying the pleasures of the blessed realm. By contrast, during the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, deceased women were identified with the goddess Hathor, and their coffins represented them explicitly as female.

“On the other hand, inequalities from this world could also be perpetuated in the tomb. Meskell’s work on burials at Deir el-Medina shows that in this community, elite women’s burial goods were often fewer and cheaper than those of their husbands; this tendency increased in proportion to the couple’s status, whereas poorer couples had relatively egalitarian simple burials (possibly, I suggest, because the woman was generating proportionally more of the household income by weaving cloth). By combining material about both genders with status, this third-wave style analysis gives a richer and more nuanced picture than the enumeration of women’s burial equipment alone would have done.”

Mixed Messages on Status and Lives of Women in Ancient Egypt

Juan Carlos Moreno García wrote:Women occupy a prominent position in ancient Egyptian iconography and mythology, and the study of their condition has certainly improved in recent times. However, the study of “women” has tended to refer in fact to the study of upper-class ladies, rendering it illusory to generalize that privileged conditions (for instance, their alleged juridical autonomy) applied to all of female society. Another limitation is that the study of Egyptian women in many cases implicitly assumes a restriction to what usually has been considered specific to the “feminine sphere” (that is, marriage, childbirth, body ornament), while aspects such as business, authority, personal initiative, and political participation are much less known. [Source Juan Carlos Moreno García, University of Paris IV-Sorbonne, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2018; escholarship.org ]

Some documents provide information about physical abuse and social misconduct (rape, adultery), while others show women involved in activities in which they exerted economic and juridical initiative, independently of their male relatives, as displayed in the will of Naunakhte and the archive of Tsenhor. Many sources attest women’s role as political actors, whether in palace conspiracies or the arrival of a new king on the throne of Egypt . Nonetheless, fundamental questions remain under-addressed and little documented. The fact that young women of modest background were subject to serfdom during the late third millennium B. C. , especially when their families were unable to pay back the debts they had contracted, points to social traditions that were apparently common in the domestic and peasant sphere.

woman grinding grain

“The fact that young women of modest background were subject to serfdom during the late third millennium BCE, especially when their families were unable to pay back the debts they had contracted, points to social traditions that were apparently common in the domestic and peasant sphere. Young women were also forced to work for institutions and the state, as weavers or merely as replacements for their male kin and, again, it is quite probable that these measures had a different impact on women depending on their social status.

Young women were also forced to work for institutions and the state, as weavers or merely as replacements for their male kin and, again, it is quite probable that these measures had a different impact on women depending on their social status. However, the use of seals and contracts, as they appear in the archaeological and documentary record of the very late third and early second millennium B. C. , together withthe widespread diffusion of the title “Lady of the House” (nbt pr), suggests that, at least, women from the “middle class” managed their own affairs and enjoyed legal initiative during this period. As sellers in markets, they probably contributed to the domestic economy thanks not only to the sale of agricultural and craft goods, but also to the sale of cloth. An interesting question is whether these activities were financed in some cases by traders. The fact that small domestic fleets collected agricultural goods and cloth from “ladies,” or that “ladies” occupied a prominent role as holders of temple land in the Wilbour Papyrus, could point to some kind of production — not necessarily ordered by institutions but aiming to supply specialized goods — in which women played an important role. In any case, late third and early second millennium funerary iconography and wooden models often represent all-female workshops in which women work as cooks and weavers.

As owners of institutional land-holdings, especially in the first millennium B. C. , women were able to transfer their property to others. Small parties organized by women, banquets, and similar activities helped cement social relations in small communities, as was true at Deir el-Medina, and they were quite probably occasions for planning marriages and for strategizing alliances (social alliances and those offering protection and promotion). Late third millennium “letters to the dead” mention conflicts related to the inheritance and division of the property of opposing wives married to the same man. Marriage agreements include clauses intended to protect the interests of brides, but the impression that women enjoyed equal rights, derived therein, might be deceptive. It could be possible that marriages were the fruit of negotiations between families and that young brides and widows had little say in these dealings, especially if they came from a modest background — possibly explaining why, in some transactions, male relatives appear as their representatives or mediators.

Finally, mistreatment and violence against women are well attested according to archaeological and papyrological evidence. In the domain of religion, women of status had access to involvement in prestigious roles in temples, especially as singers and priestesses of specific cults (most noteworthy that of Hathor). It is quite possible that the spiritual concerns of common women were rather more practical and that they were vastly different from the beliefs, hopes, and concerns expressed in official religion. Amulets suggest that the dangers associated with childbirth and children’s health/mortality were all too present in women’s lives, perhaps together with more prosaic concerns such as the evil eye. Still awaiting in-depth analysis is the sudden importance of flat female figurines associated with magical protection not only in the domestic sphere but also at a cosmopolitan level, where they were associated with negotiations within communities, a phenomenon attested across vast distances during the late third and early second millennium B. C..

Femininity in Ancient Egypt

Deborah Sweeney of Tel Aviv University wrote: “Femininity tended to be represented in terms of a woman’s role as her husband’s spouse and support, and mother of his children. Since the early 1990s Egyptologists have stressed the hegemonic yet partial nature of this representation. Religious and business activities undertaken by women can be traced by careful reading of the textual material, archaeological record, and representational material. Insights from gender archaeology, especially task distribution, can be very useful here. For instance, Wegner has used the distribution patterns of women’s seal impressions at the Middle Kingdom town of Abydos to demonstrate the scope of their sealing practices as mayor’s wife, female head- of-household (nbt-pr), or domestic administrator (jrjt-at) in and around various buildings in the town. [Source: Deborah Sweeney, Tel Aviv University, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“On the other hand, many of the salient themes of masculinity (status, rivalry) are extremely difficult to find in material about women due to the partial nature of the record—for instance, Egyptian literary texts rarely represent women speaking to one another, which is clearly counterfactual. By contrast, women from the Egyptian royal house are relatively well known through the monumental record and their burials, even though their lives were atypical for Egyptian women and strongly imprinted by the ideology of kingship. Recent work on Egyptian queenship has highlighted the role of the women who were closest to the king. This particular form of femininity was far more closely integrated with the role of spouse than any other: it is almost impossible to imagine an Egyptian queen without a king. Even as queen regent for a minor son, the queen nonetheless stood in relation to the king.

“Queenship also had a far more heightened connection to deity than other forms of femininity. Ideologically, the queens fulfilled the role of various goddesses who nourished and supported the sun god, with whom the king was equated: the daughter who defended him, and the consort who regenerated him by giving birth to him after making love with him. If queens were represented in temple reliefs, they were normally depicted playing a supportive role, accompanying the king when he made offerings and chanting and playing the sistrum to appease the deity. During the Amarna Period, however, queens took a more active part: Nefertiti is represented offering sacrifices in her own right. The Hwt-bnbn, one of the temples Akhenaten built at Karnak in the early years of his reign, features Nefertiti alone making offerings, without any remembrance of Akhenaten. During Akhenaten’s reign, and that of his father, Amenhotep III, the chief queens adopted certain features of the masculine aspects of royal iconography: for instance, both Tiy and Nefertiti are represented attacking and subduing the female enemies of Egypt.”

Women's Legal Rights in Ancient Egypt

Peter A. Piccione wrote in “The Status of Women in Ancient Egyptian Society”: “The Egyptian woman's rights extended to all the legally defined areas of society. From the bulk of the legal documents, we know that women could manage and dispose of private property, including: land, portable goods, servants, slaves, livestock, and money (when it existed), as well as financial instruments (i.e., endowments and annuities). A woman could administer all her property independently and according to her free will. She could conclude any kind of legal settlement. She could appear as a contracting partner in a marriage contract or a divorce contract; she could execute testaments; she could free slaves; she could make adoptions. She was entitled to sue at law. It is highly significant that a woman in Egypt could do all of the above and initiate litigation in court freely without the need of a male representative. This amount of freedom was at variance with that of the Greek woman who required a designated male, called a kourios, to represent or stand for her in all legal contracts and proceedings. This male was her husband, father or brother. [Source: Peter A. Piccione, College of Charleston,“The Status of Women in Ancient Egyptian Society,” 1995, Internet Archive, from NWU -]

Nefertari

“Egyptian women had the right to bring lawsuits against anyone in open court, and there was no gender-based bias against them, and we have many cases of women winning their claims. A good example of this fact is found in the Inscription of Mes. This inscription is the actual court record of a long and drawn-out private land dispute which occurred in the New Kingdom. Significantly, the inscription shows us four things: (1) women could manage property, and they could inherit trusteeship of property; (2) women could institute litigation (and appeal to the court of the vizier); (3) women were awarded legal decisions (and had decisions reversed on appeal); (4) women acted as witnesses before a court of law. -

“However, based upon the Hermopolis Law Code of the third century B.C., the freedom of women to share easily with their male relatives in the inheritance of landed property was perhaps restricted somewhat. According to the provisions of the Hermopolis Law Code, where an executor existed, the estate of the deceased was divided up into a number of parcels equal to the number of children of the deceased, both alive and dead. Thereafter, each male child (or that child's heirs), in order of birth, took his pick of the parcels. Only when the males were finished choosing, were the female children permitted to choose their parcels (in chronological order). The male executor was permitted to claim for himself parcels of any children and heirs who predeceased the father without issue. Female executors were designated when there were no sons to function as such. However, the code is specific that — unlike male executors — they could not claim the parcels of any dead children. -

“Still, it is not appropriate to compare the provisions of the Hermopolis Law Code to the Inscription of Mes, since the latter pertains to the inheritance of an office, i.e., a trusteeship of land, and not to the land itself. Indeed, the system of dividing the estate described in the law code — or something similar to it — might have existed at least as early as the New Kingdom, since the Instructions of Any contains the passage, "Do not say, 'My grandfather has a house. An enduring house, it is called' (i.e., don't brag of any future inheritance), for when you take your share with your brothers, your portion may only be a storehouse." -

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024