Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

WOMEN'S LEGAL RIGHTS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Nefertari

Peter A. Piccione wrote in “The Status of Women in Ancient Egyptian Society”: “The Egyptian woman's rights extended to all the legally defined areas of society. From the bulk of the legal documents, we know that women could manage and dispose of private property, including: land, portable goods, servants, slaves, livestock, and money (when it existed), as well as financial instruments (i.e., endowments and annuities). A woman could administer all her property independently and according to her free will. She could conclude any kind of legal settlement. She could appear as a contracting partner in a marriage contract or a divorce contract; she could execute testaments; she could free slaves; she could make adoptions. She was entitled to sue at law. It is highly significant that a woman in Egypt could do all of the above and initiate litigation in court freely without the need of a male representative. This amount of freedom was at variance with that of the Greek woman who required a designated male, called a kourios, to represent or stand for her in all legal contracts and proceedings. This male was her husband, father or brother. [Source: Peter A. Piccione, College of Charleston,“The Status of Women in Ancient Egyptian Society,” 1995, Internet Archive, from NWU -]

“Egyptian women had the right to bring lawsuits against anyone in open court, and there was no gender-based bias against them, and we have many cases of women winning their claims. A good example of this fact is found in the Inscription of Mes. This inscription is the actual court record of a long and drawn-out private land dispute which occurred in the New Kingdom. Significantly, the inscription shows us four things: (1) women could manage property, and they could inherit trusteeship of property; (2) women could institute litigation (and appeal to the court of the vizier); (3) women were awarded legal decisions (and had decisions reversed on appeal); (4) women acted as witnesses before a court of law. -

“However, based upon the Hermopolis Law Code of the third century B.C., the freedom of women to share easily with their male relatives in the inheritance of landed property was perhaps restricted somewhat. According to the provisions of the Hermopolis Law Code, where an executor existed, the estate of the deceased was divided up into a number of parcels equal to the number of children of the deceased, both alive and dead. Thereafter, each male child (or that child's heirs), in order of birth, took his pick of the parcels. Only when the males were finished choosing, were the female children permitted to choose their parcels (in chronological order). The male executor was permitted to claim for himself parcels of any children and heirs who predeceased the father without issue. Female executors were designated when there were no sons to function as such. However, the code is specific that — unlike male executors — they could not claim the parcels of any dead children. -

“Still, it is not appropriate to compare the provisions of the Hermopolis Law Code to the Inscription of Mes, since the latter pertains to the inheritance of an office, i.e., a trusteeship of land, and not to the land itself. Indeed, the system of dividing the estate described in the law code — or something similar to it — might have existed at least as early as the New Kingdom, since the Instructions of Any contains the passage, "Do not say, 'My grandfather has a house. An enduring house, it is called' (i.e., don't brag of any future inheritance), for when you take your share with your brothers, your portion may only be a storehouse." -

RELATED ARTICLES:

WOMEN IN ANCIENT EGYPT: STATUS, FEMININITY AND IDEAS ABOUT GENDER africame.factsanddetails.com ;

WOMEN'S ROLES IN ANCIENT EGYPT: MOTHERS, WIVES, WORKERS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

FAMILIES IN ANCIENT EGYPT: HOUSEHOLDS, PARENTS AND CHILDREN africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MARRIAGE, DIVORCE AND LOVE IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Dancing for Hathor: Women in Ancient Egypt” by Carolyn Graves-Brown (2010) Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Egypt” by Gay Robins (1993) Amazon.com;

Women in Ancient Egypt: Revisiting Power, Agency, and Autonomy

by Mariam F. Ayad (2022) Amazon.com;

“Women In Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Watterson (1998) Amazon.com;

“The Royal Women of Amarna: Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt" (1996) Amazon.com;

“Women & Society in Greek & Roman Egypt” by Jane Rowlandson (1998) Amazon.com;

“Women, Gender and Identity in Third Intermediate Period Egypt: The Theban Case Study” by Jean Li (2017) Amazon.com;

“When Women Ruled the World: Six Queens of Egypt” by Kara Cooney (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Cleopatras: Discover the Powerful Story of the Seven Queens of Ancient Egypt!” by Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones (2024) Amazon.com;

”Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh” by Joyce A. Tyldesley (1998) Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Sexual Equality in Ancient Egypt

Dr Joann Fletcher of the University of York wrote for BBC: “In order to understand their relatively enlightened attitudes toward sexual equality, it is important to realise that the Egyptians viewed their universe as a complete duality of male and female. Giving balance and order to all things was the female deity Maat, symbol of cosmic harmony by whose rules the pharaoh must govern. [Source: Dr Joann Fletcher, BBC, February 17, 2011. Fletcher is an Honorary Research Fellow at the University of York and part of the University’s Mummy Research Group |::|]

Isis bringing Osiris back from the dead

“The Egyptians recognised female violence in all its forms, their queens even portrayed crushing their enemies, executing prisoners or firing arrows at male opponents as well as the non-royal women who stab and overpower invading soldiers. Although such scenes are often disregarded as illustrating 'fictional' or ritual events, the literary and archaeological evidence is less easy to dismiss. Royal women undertake military campaigns whilst others are decorated for their active role in conflict. Women were regarded as sufficiently threatening to be listed as 'enemies of the state', and female graves containing weapons are found throughout the three millennia of Egyptian history. |::|

“Although by no means a race of Amazons, their ability to exercise varying degrees of power and self-determination was most unusual in the ancient world, which set such great store by male prowess, as if acknowledging the same in women would make them less able to fulfil their expected roles as wife and mother. Indeed, neighbouring countries were clearly shocked by the relative freedom of Egyptian women and, describing how they 'attended market and took part in trading whereas men sat and home and did the weaving', the Greek historian Herodotus believed the Egyptians 'have reversed the ordinary practices of mankind'. |::|

“And women are indeed portrayed in a very public way alongside men at every level of society, from co-ordinating ritual events to undertaking manual work. One woman steering a cargo ship even reprimands the man who brings her a meal with the words, 'Don't obstruct my face while I am putting to shore' (the ancient version of that familiar conversation 'get out of my way whilst I'm doing something important'). |::|

“Egyptian women also enjoyed a surprising degree of financial independence, with surviving accounts and contracts showing that women received the same pay rations as men for undertaking the same job-something the UK has yet to achieve. As well as the royal women who controlled the treasury and owned their own estates and workshops, non-royal women as independent citizens could also own their own property, buy and sell it, make wills and even choose which of their children would inherit.” |::|

Women's Property Rights in Ancient Egypt

Peter A. Piccione wrote in “The Status of Women in Ancient Egyptian Society”: “There were several ways for an Egyptian woman to acquire possessions and real property. Most frequently, she received it as gifts or as an inheritance from her parents or husband, or else, she received it through purchases — with goods which she earned either through employment, or which she borrowed. Under Egyptian property law, a woman had claim to one-third of all the community property in her marriage, i.e. the property which accrued to her husband and her only after they were married. When a woman brought her own private property to a marriage (e.g., as a dowry), this apparently remained hers, although the husband often had the free use of it. However, in the event of divorce her property had to be returned to her, in addition to any divorce settlement that might be stipulated in the original marriage contract. [Source: Peter A. Piccione, College of Charleston,“The Status of Women in Ancient Egyptian Society,” 1995, Internet Archive, from NWU -]

“A wife was entitled to inherit one-third of that community property on the death of her husband, while the other two-thirds was divided among the children, followed up by the brothers and sisters of the deceased. To circumvent this possibility and to enable his wife to receive either a larger part of the share, or to allow her to dispose of all the property, a husband could do several things: -

“1) In the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.), he could draw up an imyt-pr, a "house document," which was a legal unilateral deed for donating property. As a living will, it was made and perhaps executed while the husband was still alive. In this will, the husband would assign to his wife what he wished of his own private property, i.e., what he acquired before his marriage. An example of this is the imyt-pr of Wah from el-Lahun. 2) If there were no children, and the husband did not wish his brothers and sisters to receive two-thirds of the community property, he could legally adopt his wife as his child and heir and bequeath all the property to her. Even if he had other children, he could still adopt his wife, so that, as his one of his legal offspring, she would receive some of the two-thirds share, in addition to her normal one-third share of the community property. -

“A woman was free to bequeath property from her husband to her children or even to her own brothers and sisters (unless there was some stipulation against such in her husband's will). One papyrus tells us how a childless woman, who after she inherited her husband's estate, raised the three illegitimate children who were born to him and their female household slave (such liaisons were fairly common in the Egyptian household and seem to have borne no social stigma). She then married the eldest illegitimate step-daughter to her younger brother, whom she adopted as her son, that they might receive the entire inheritance. -

“A woman could also freely disinherit children of her private property, i.e., the property she brought to her marriage or her share of the community property. She could selectively bequeath that property to certain children and not to others. Such action is recorded in the Will of Naunakht. -

Women in Contracts in Ancient Egypt

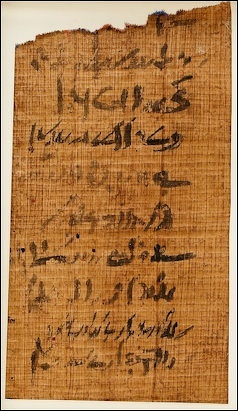

marriage contract

Peter A. Piccione wrote: “Women in Egypt were consistently concluding contracts, including: marriage and divorce settlements, engagements of wet-nurses, purchases of property, even arrangements for self-enslavement. Self-enslavement in Egypt was actually a form of indentured servitude. Although self-enslavement appears to have been illegal in Egypt, it was practiced by both men and women. To get around the illegality, the servitude was stipulated only for a limited number of years, although it was usually said to be "99 years." [Source: Peter A. Piccione, College of Charleston,“The Status of Women in Ancient Egyptian Society,” 1995, Internet Archive, from NWU -]

“Under self-enslavement, women often technically received a salary for their labor. Two reasons for which a woman might be forced into such an arrangement are: (1) as payment to a creditor to satisfy bad debts; (2) to be assured of one's provisions and financial security, for which a person might even pay a monthly fee, as though they were receiving a service. However, this fee would equal the salary that the provider had to pay for her labor; thus, no "money" would be exchanged. Since this service was a legal institution, then a contract was drawn up stipulating the conditions and the responsibilities of the involved parties. -

“In executing such an arrangement, a woman could also include her children and grandchildren, alive or unborn. One such contract of a woman who bound herself to the temple of Saknebtynis states: “The female servant (so & so) has said before my master, Saknebtynis, the great god, 'I am your servant, together with my children and my children's children. I shall not be free in your precinct forever and ever. You will protect me; you will keep me safe; you will guard me. You will keep me sound; you will protect me from every demon, and I will pay you 1-1/4 kita of copper . . . until the completion of 99 years, and I will give it to your priests monthly.' If such women married male "slaves," the status of their children depended on the provisions of their contracts with their owners.” -

Women in Public in Ancient Egypt

Peter A. Piccione of the College of Charleston wrote in “The Status of Women in Ancient Egyptian Society”: “The Egyptian woman in general was free to go about in public; she worked out in the fields and in estate workshops. Certainly, she did not wear a veil, which is first documented among the ancient Assyrians (perhaps reflecting a tradition of the ancient semitic-speaking people of the Syrian and Arabian Deserts). [Source: Peter A. Piccione, College of Charleston,“The Status of Women in Ancient Egyptian Society,” 1995, Internet Archive, from NWU -]

“However, it was perhaps unsafe for an Egyptian woman to venture far from her town alone. Ramesses III boasts in one inscription, "I enabled the woman of Egypt to go her own way, her journeys being extended where she wanted, without any person assaulting her on the road." A different view of the traveling women is found in the Instructions of Any, "Be on your guard against a woman from abroad, who is not known in town, do not have sex with her." So by custom, there might have been a reputation of impiousness or looseness associated with a woman traveling alone in Egypt. -

Despite the legal freedom of women to travel about, folk custom or tradition may have discouraged that. So, e.g., earlier in the Old Kingdom, Ptahhotep would write, "If you desire to make a friendship last in a house to which you have access to its master as a brother or friend in any place where you might enter, beware of approaching the women. It does not go well with a place where that is done." However, the theme of this passage might actually refer to violating personal trust and not the accessibility of women, per se. However, mores and values apparently changed by the New Kingdom. The love poetry of that era, as well as certain letters, are quite frank about the public accessibility and freedom of women. -

Women and Crime in Ancient Egypt

According to a 19th century source: There were of course plenty of women who did not belong to “good women “(that is to the respectable class); as in other countries of antiquity, these women were often those whose husbands had left them, and who traveled about the country. The strange woman was therefore always a suspicious character; "beware," says the wise man, "of a woman from strange parts, whose city is not known. When she comes do not look at her nor know her. She is as the eddy in deep water, the depth of which is unknown. The woman whose husband is far off writes to thee every day. If no witness is near her she stands up and spreads out her net: O! fearful crime to listen to her! “Therefore he who is wise avoids her and takes to himself a wife in his youth; first, because a man's own house is "the best thing "; secondly, because "she will present thee with a son like unto thyself". It seems to have been a common crime amongst the workmen to “assault strange women." [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Peter A. Piccione wrote: “These ordinary and extraordinary roles are not the only ones in which we see Egyptian women cast in ancient Egypt. We also see Egyptian women as the victims of crime (and rape); also as the perpetrators of crime, as adulteresses and even as convicts. [Source: Peter A. Piccione, College of Charleston,“The Status of Women in Ancient Egyptian Society,” 1995, Internet Archive, from NWU -]

“Women criminals certainly existed, although they do not appear frequently in the historical record. A woman named Nesmut was implicated in a series of robberies of the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings during the Twentieth Dynasty. Examples of women convicts are also known. According to one Brooklyn Museum papyrus from the Middle Kingdom, a woman was incarcerated at the prison at Thebes because she fled her district to dodge the corvee service on a royal estate. Most of the concubines and lesser wives involved in the harim conspiracy against Ramesses III were convicted and had their noses and ears cut off, while others were invited to commit suicide. Another woman is indicated among the lists of prisoners from a prison at el-Lahun. However, of the prison lists we have, the percentage of women's names is very small compared to those of men, and this fact may be significant. -

Uroš Matić wrote: Gender and violence intersected in ancient Egypt in many ways. In general, the ancient Egyptian gender system privileged men and the masculine. Exceptions to this were status dependent. Gendered patterns of violence are evident in cases of mistreatment of women through beating and rape. War-related royal texts used gendered language to frame enemies as feminine and place them lower on the hierarchy vis-à-vis the pharaoh. Enemies were also feminized in visual representations such as temple reliefs. The symbolic violence of gendered language also served to establish indigenous gender hierarchies. Although there is evidence that some Egyptian queens and female rulers organized military operations, there is no evidence for the participation of women in war. In contrast, some goddesses had a strong affiliation with war and violence and were frequently associated with the pharaoh in this regard. [Source: Uroš Matić, Austrian Archaeological Institute's Cairo Branch, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2021]

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Gender-Violence by Uroš Matić escholarship.org

Gender Difference in Violence and Trauma in Ancient Egypt

So far, only some studies explicitly mention sex-based patterns behind traces of trauma and differences in health status or life expectancy. It has been reported, based on the study by Azza Sarry el-Din (2003) of 271 skeletons from Old Kingdom cemeteries at Giza, that the highest incidence of bone fractures occurred in male workers (43.75 percent), while bone fractures occurred in 20.73 percent of male high officials. Bone fractures occurred in 26.41 percent of female workers and 16.66 percent of female elite. Sex-based differences in the percentages were thus most prominent between the workers. The study showed that the most affected bone was the right ulna. Head injuries were also higher among the workers. Clearly, being a woman of the working class meant being exposed to more injuries than being a woman of the elite.

The effects of structural violence based on both gender and socioeconomic status mean that most impacted people in this sample are non-elite men and the least impacted are the elite women. Evidence from the analysis of 257 skeletons from Tell el-Dabaa (ancient Avaris, capital of the Hyksos kingdom) indicates that during the Second Intermediate Period women had significantly lower life expectancy (30 years) than men, whose life expectancy was 34.4 years. It cannot be excluded that this is the consequence of gendered structural violence. Joyce Filer analyzed 1,726 Late Period skulls from Giza known as the E series, dating from the 26th to the 30th dynasties. Injuries were present in 21 crania (1.2 percent), the majority of which were of mature to elderly individuals. Twelve were male, or probably male, four were female, or probably female, and for five skulls the sex could not be determined.

Severe gashes and incomplete and complete slice injuries consistent with attacks from swords, axes, and crushing weapons were detected. These are suggestive of militaristic behavior and seem to have affected men in this group more than women. Whereas there is some evidence for difference in rates of trauma in the Old Kingdom — female workers appear to have been more exposed to trauma than the female elite — and whereas there is evidence that women had a lower life expectancy in the Hyksos capital during the Second Intermediate Period, until now there is no indication of a clear gender pattern in Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt. The results of bioarchaeological investigations by Moushira Erfan et al. (2009) of cranial trauma at Bahriya Oasis during the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods showed that 31 (19.4 percent) out of 160 crania showed traces of trauma, with similar percentages between men (18.6 percent) and women (20.6 percent). The highest prevalence of injury was exhibited on the parietal bone (65.9 percent), followed by the frontal bone (27.3 percent) and occipital bone (6.8 percent). Depression fractures were present in 88.6 percent of the trauma events, and blade injuries in 11.7 percent. The authors of the study argued that Roman rule in Egypt contributed to violence inasmuch as the population experienced social stress, which ultimately manifested in interpersonal violence.

Some interesting evidence of gendered violence comes from Nubia, Egypt’s southern neighboring culture. Joyce Filer analyzed 309 skulls from the Eastern Cemetery at Kerma, of which 34 (11 percent) showed head injuries. The majority of these individuals were mature to old and had mainly oval and depressed head lesions, consistent with attack from stones, sticks, maces, and clubs. According to Filer these types of injuries indicate domestic disputes. Out of 34 individuals with such injuries 44.1 percent were women, which in Filer’s opinion must necessarily be explained by non-military disputes because she assumes that women in Nubia were not militarily active. Margaret Judd showed that there was no statistical significance behind the gender distribution of injuries for her sample of individuals from the Kerma Period (around 2,500 – 1,500 B.C.) in Sudan. Multiple injuries were found on the crania and long bones of female individuals from both rural and urban Kerma communities, which led her to the conclusion that women of varying social standing were equally exposed to interpersonal violence. We see here a marked contrast with Egypt, where differences in, for example, life expectancy or frequency of injuries were both gender and class dependent. It has been recently suggested, based on evidence from Tombos, that New Kingdom Egyptian rule in Nubia influenced the local society in such a way that the frequency of interpersonal violence.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024