Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

INHERITANCE IN ANCIENT EGYPT

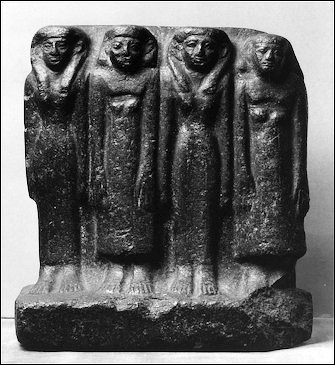

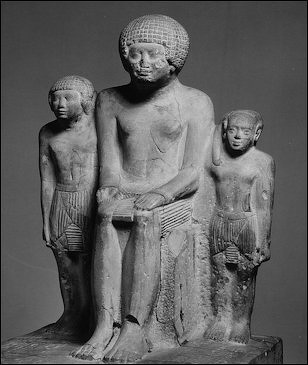

family of three --- one man, two women

Sandra Lippert of Universität Tübingen in Germany wrote: “In ancient Egypt inheritance was conveyed either through the legal order of succession, favoring sons over daughters, children over siblings, and older over younger, or through written declarations that allowed for individualized arrangements. Adoption was the common means by which a childless person could acquire an heir. The initial tendency towards a sole heir (preferably the eldest son) was replaced by the division of parental property among all children, although the eldest son continued to play an important role as trustee for his siblings and received a larger or better share according to the legal order of succession. Documents used for the bequeathing of inheritance varied over time and were gradually replaced by donations and divisions after the Middle Kingdom. Effectiveness only after the death of the issuer is rarely mentioned explicitly. [Source: Sandra Lippert, Universität Tübingen, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“In ancient Egypt the process of inheritance was ideally represented in the scenario of the firstborn son inheriting the property of his deceased father, while at the same time carrying out the duty to bury him and take care of the other family members. This situation (with the exception of the care for siblings) was portrayed prototypically in the mythological constellation of Osiris and Horus. Since in reality various factors could render this ideal scenario impossible or at least undesirable to execute—perhaps there were no male children, or no children at all, or the eldest son was not trustworthy or was otherwise unsuited—Egyptian law prepared for these eventualities and allowed for intentional changes in the succession. “Like modern societies, that of ancient Egypt developed two complementary systems of inheritance, which can be traced back almost to the beginning of Pharaonic history: the legal order of succession and that established through a written declaration of intent, with the last overruling the first. The Egyptian word jwaw was used not only for the factual heir after the death of the bequeather but also for the possible or future heir, i.e., the person who, through either the legal order of succession or a will document, was supposed to become an heir. Although the basic principles of inheritance seem to have remained quite stable, there were particular developments in the practice and the details of the laws. However, since sources are rare before the Late Period (712–332 B.C.), it is difficult to deduce exactly how and when changes occurred.”

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Kinship and Family in Ancient Egypt: Archaeology and Anthropology in Dialogue”

by Leire Olabarria (2020) Amazon.com;

“Households in Context: Dwelling in Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt” by Caitlín Eilís Barrett and Jennifer Carrington (2024) Amazon.com;

“Childhood in Ancient Egypt” by Amandine Marshall and Colin Clement (2022) Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

“The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt: A Genealogical Sourcebook of the Pharaohs” Amazon.com;

”Private Lives of the Pharaohs: Unlocking the Secrets of Egyptian Royalty” by Joyce Tyldesley (2001) Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Egypt” by Gay Robins (1993) Amazon.com;

“Daughters of Isis: Women of Ancient Egypt” by Joyce Tyldesley (1994) Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Inheritance and Maintaining Family Power in Ancient Egypt

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: “Finally, sources are most explicit when dealing with strategies undertaken by powerful households to preserve their power bases. 6th Dynasty inscriptions from Akhmim show, for instance, that a high official called Tjeti- Kaihep abandoned a very promising career at the court, in Memphis, and returned to Akhmim in order to replace his (prematurely deceased?) elder brother as chief of the local temple and “great overlord of the nome,” two positions traditionally held by his family and which ensured them a leading role in the province. Apparently, Tjeti-Kaihep preferred to control the traditional, local power-base of his family instead of developing a high- ranking career in the capital. In the case of the Middle Kingdom governor Khnumhotep II of Beni Hassan, his claim to his position was hereditary right and royal favor, and his autobiography illustrates the degree to which power-blocks cemented by marriage alliances could arise, based on the control of some provinces, on positions held at court, and on connections with other powerful families. Other inscriptions show that the position of governor of a city, held for generations within a family, could be sold to a member of the kin-group (hAw) and thus preserved within the extended family. Even at a modest level, buying and selling official positions (such as priestly office) prevented a household from losing control over institutional income and sources of power. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“In fact, the transmission of the household to the next generation was always a delicate affair. The elder son usually inherited a larger share of the family possessions, with the obligation to bury his parents and perform rituals in their honor. However, the family ideology was strong enough to mask other forms of transmission within a set of fictitious kin expressions (e.g., the simultaneous existence of several “elder sons,” pseudo-adoptions, etc.). Significantly, the transfer of permanent legal rights to own and bequeath property was established by means of a document called jmjt-pr (lit. “what is in the house”). In the end, family ideology was a powerful tool that not only ensured the cohesion of the household and preserved its identity, but also provided alternative values to the official ones. Multiple burials, the cult of dead relatives, the display of genealogies and pride of lineage, and economic self-sufficiency figure prominently as its most conspicuous elements.”

Legal Order of Succession for Inheritance in Ancient Egypt

family of four

Sandra Lippert of Universität Tübingen in Germany wrote: “In earlier periods the purpose of the legal order of succession seems, tentatively speaking, to have been the creation of a sole (male) heir. It is to be assumed that he had a certain moral, although probably not legal, obligation to care for his non-inheriting relatives. The defendant in Papyrus Berlin P 9010 from the 6th Dynasty alludes to this system when he claims, without referring to any documents, that his father’s property should remain with him because the will brought forth by the other party was not authentic. [Source: Sandra Lippert, Universität Tübingen, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“In the early New Kingdom this principle is already weakened: the heir is no longer a sole one with mere moral obligations to support his siblings, but rather acts as rwDw—that is, caretaker administrating the estate—who must deal out the profits equitably. However, the rwDw did not always meet his obligation towards his siblings. In such cases, the law courts of the later New Kingdom went even further to strengthen the siblings’ position. This stance might lie behind the developments described in the 19th Dynasty Inscription of Mes: some disputed land had originally (i.e., in the 18th Dynasty) been passed, undivided, to heir after heir who acted as rwDw-caretakers for their non-inheriting relatives, but when arguments arose concerning the distribution of the income, a later court decided to split the land into parcels for each descendant, thus allowing those who belonged to the same level of kinship as the main heir more direct access to a share of the inheritance. This decision was later contested by the decendants of the original caretakers, who wanted to be reinstated into their more advantageous position. A similar case is treated in the broadly contemporaneous P. Berlin P 3047: one member of the community of heirs sues his brother/caretaker because he had not been allowed to profit from his share of the inheritance. In court, the rwDw admits the brother’s right and declares his consent to splitting the plaintiff’s share off the inheritance; it is then rented to a temple to ensure an income.

“The struggle between the older principle of sole heirship and the later one of division between the descendants still had not been fully resolved in the 20th Dynasty, as can be seen in the complaint on P. Cairo CG 58092 recto: The writer recounts how he refuted the demands of his siblings for their shares of the inheritance from their parents. Interestingly, his argument is not that he is the eldest but that he alone had borne the financial burden of the parents’ burials.

“The Codex Hermupolis, a third century B.C. manuscript transmitting to us a part of the Egyptian law code collected under Darius I, also covers the topic of inheritance. The passages concerning the legal order of succession show that, by the Late Period, the rights of the other siblings as co-heirs have finally been fully acknowledged: the eldest son (here always used as prototypical legal heir) still takes possession of the property of his father and may even sell part of it, but as soon as his younger siblings demand their shares, even without any allusion to mismanagement on his part, he is obligated to divide it (or the price received), although he himself retains the most advantageous position, being entitled to a better or larger (e.g., double) share.

“While inherited land could be split up into single plots (even if this was sometimes avoided), division was difficult when the inherited object was a house. In Codex Hermupolis, column 9.19-9.21, such a case is dealt with. The pattern of division followed that of other possessions but, as many documents of the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods show, the shares were virtual, the house itself remaining “without division”: it was not converted into separate apartments for each co-owner but was held jointly, and the profit, if the eldest son sold it, had to be divided by him among his siblings according to the size of their shares when they demanded to receive them.

“The eldest son additionally received the shares of those siblings who died childless. This privilege was, however, not shared by a daughter if she, in the absence of male children, became legal heir. Furthermore, the eldest son was the only heir allowed to prove his claims to objects simply by referring, without documentation, to the fact that he inherited them from his father; all other heirs had to prove their title by producing the document through which they had gained it. In sales documents, this title by legal succession seems occasionally to be referred to as nty mtw.y (n) wS sX, “which belongs to me without document”. Property that the father had given as a gift to one of the younger children before his death was no longer considered part of the estate; if no donation document existed, the presentee had to take an oath.”

Requirements for the Legal Heir in Ancient Egypt

Sandra Lippert of Universität Tübingen wrote: “In the ideal case, the legal (i.e., the sole or principal) heir was the firstborn male child of the deceased. If there was no person fulfilling these requirements, the next best candidate stepped into his place. Of the three categories in which the heir had to qualify, a closer degree of kinship was more important than gender, which in turn was more important than order of birth. Thus, for example, a daughter became legal heir only if there were no male children, whether older or younger than herself, and a brother became legal heir only if there were no children, whether male or female. The most complete evidence for this hierarchy comes from the Late Period, but it is plausible that it had not changed over time, as occasional glimpses from earlier periods show. [Source: Sandra Lippert, Universität Tübingen, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The role of kinship: Children of the deceased preceded siblings of the same as legal heirs, as can already be seen in the Old Kingdom (2649–2150 B.C.) from the order in which they were listed in enumerations of possible heirs. Gödecken assumes an equality between the inheritance rights of children and siblings by referring to the Inscription of Penmeru and P. Berlin P 9010, but these texts deal with dispositions of property by document, not with legal succession, while the Inscription of Kaemnofret, as mentioned above, consistently names children before brothers and sisters. That siblings inherited if there were no children is mentioned explicitly in Codex Hermupolis column 9.3-9.4 and 9.17. It is possible that parents inherited if there were neither children nor siblings, but such a scenario is not attested and was probably quite rare. Spouses were not considered heirs in the legal order of succession.

family of three

“The role of gender: While Egyptian women held property independently from their husbands and there are numerous attestations of their ability to pass it on to whomever they liked, in the legal order of succession there is a clear preference for male children: male children preceded female children as legal heirs, regardless of their age. When the inheritance was divided into lots among the siblings according to Late Period practice, sons chose their lots before daughters. Only if there were no sons could a daughter step into the position of legal heir and administer the estate for her younger sisters (also the woman who acted as administrator for her co-heirs, mentioned in the Inscription of Mes). In such a situation a daughter was not allowed to take the shares of sisters who had died childless; instead the whole inheritance was divided by the number of surviving siblings plus one and she received a double share. It is possible that the rule “male before female” also applied to other categories of relatives (siblings and parents), but there is no evidence to support it. 4. The role of the order of birth.

“The role of the order of birth: Among children of the same gender, older children always preceeded younger ones in the legal order of succession; the ideal heir was the sA smsw/Sr aA, “eldest son.” In some monuments of the Old Kingdom, there can, however, be found more than one sA smsw. Whether this is to be explained by the first one having died and the second having then taken his title, by multiple marriages each resulting in one “eldest son,” or even by a sort of testamentary decision of the father who, by artifically creating more than one “eldest son” (the testator’s ability to name an “eldest son” is explained below), decided to divide the property equally between them, is yet to be determined. This preference of older over younger also applied to siblings, at least partially: if someone died childless, his share of the paternal property fell to his eldest brother, but the same was not true for an all-female group of siblings.

Role of the organization and financing of the burial: The strong connection between the burial of the deceased and the inheritance of his property is already visible in the Inscription of Tjenti of the 5th Dynasty. But from at least the Second Intermediate Period onwards, when the injunction “Bury him, succeed into his inheritance!” is attested on a ceramic bowl in the Pitt Rivers Museum, this connection took on a life of its own, ultimately resulting in a law, “The property is given to the one who buries,” cited in P. Cairo CG 58092 recto and referred to obliquely in Ostracon Petrie 16 of the 20th Dynasty. Thus the duty to bury changed from being a consequence of the inheritance to a prerequisite. This law seems mainly to have been invoked to defend the position of sole heir against relatives who would have had a right to a share under the later legal practice.”

Adoption as a Way to Establish an Heir for the Childless

Sandra Lippert of Universität Tübingen wrote: “Although Egyptian laws on legal succession allowed the inheritance to fall to siblings if there were no descendants, a child, especially a son, as heir was considered much more desirable. Childless Egyptians were expected to adopt an orphan, who would then act for them as their “eldest son”. In the case of the 19th Dynasty couple Ramose and Mutemwia, an adoption seems to have followed after several prayers for a child had remained unanswered. [Source: Sandra Lippert, Universität Tübingen, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“An adopted child had the same rights of inheritance as a biological child. An exception is given in the priestly rules resumed in the Roman Period Gnomon of the Idios Logos (§ 92): a foundling adopted by a priest could not become a priest himself because the candidates for this office had to be from pure priestly bloodlines.

“Since wives could not inherit from their husbands in the legal order of succession, there are one or two cases from the New Kingdom of a childless husband actually adopting his wife. Slaves could also be adopted for the same purpose: After her husband’s death, the childless Nanefer emancipates and adopts a slave woman and her children, most likely fathered by Nanefer’s husband; additionally, she marries the eldest of the girls to her (Nanefer’s) brother whom she also adopts. It remains unclear whether adoption was only possible through a written declaration of the adopter or could also have become effective without a document, e.g., by public announcement.”

Wills and Inheritance Documents in Ancient Egypt

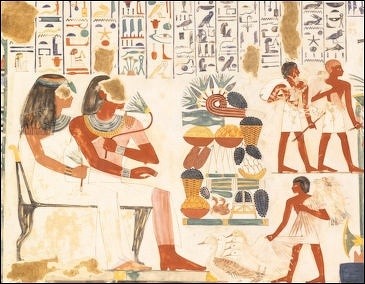

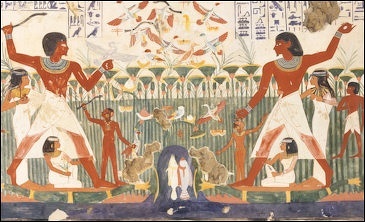

Nakht family outing

Sandra Lippert of Universität Tübingen wrote: “If a person wanted to bequeath his property to a person or persons other than the one who would have inherited in the legal order of succession, or to ensure and stress the inheritance rights of a certain person (even though he might have been the legal heir anyway), to allot objects or shares of different sizes to specific persons, to impose special terms, or to exclude someone from the inheritance, he had to draw up a document. Depending on the era, but also on how the inheritance was to be distributed, different types of documents were used. Modern legal historians are sometimes reluctant to use the term “testament” for these documents since they do not conform to the Roman legal definition of “testamentum”. In fact, the Egyptians avoided stating explicitly within such documents that they were meant to become effective only upon the death of the issuer—the reason being the well- known Egyptian belief in the power of the written word to create reality. However, Egyptian documents did not usually become effective upon the date of their being drawn up but at the moment they were handed over to the beneficiary, which might easily have been delayed until after the issuer’s death by depositing it with a trustworthy third party. There are only two known Egyptian will documents in which the death of the testator is alluded to: P. Vienna KHM Dem. 9479, a division document, and Moscow 123, a fictitious sale. Both date to the first century B.C. and seem influenced by Greek wills. As a measure against later litigation among heirs, testators sometimes had all beneficiaries (and sometimes even those relatives who did not inherit) agree on a document. [Source: Sandra Lippert, Universität Tübingen, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The jmt pr is the best-known type of will document. The term jmt pr has variously been interpreted as “that which is in the house” or “that which the house is in”, both of which are equally unsatisfactory translations. The assets that are transferred through jmt-pr documents are typically land, sometimes with appurtenant personnel, but also offices. Opinions about the purpose of jmt-pr documents differ, they being variously interpreted as documents regulating complicated situations, including donations and property transfers against payment, documents for the incomplete transfer of rights among family members and co-opted persons, and wills in favor of persons who otherwise would not inherit. In considering all the evidence, there can be no doubt that jmt-pr documents were used as wills: jmt-pr documents transfer property gratuitously: “to give away by jmt pr” is regularily contrasted with “to give for a price (i.e., to sell)” in regulations relating to private funerary foundations from the Old Kingdom. Since in earlier periods offices could not be sold but only transferred by jmt pr, there are a few cases of jmt-pr documents having been drawn up in connection with deposits or loans that were not repaid, with the office (or rather the will concerning the office) acting as security or compensation, but this does not mean that the jmt pr itself documented a transfer against payment.

“Jmt-pr documents did not become effective immediately but after the death of the issuer: In Papyrus UC 32037 of the 12th Dynasty, an earlier jmt-pr document was revoked and a new one put in its place; this would not have been possible if the first one had already been valid from the date of writing. Moreover, the jmt pr was so closely linked to succession and inheritance that it had to be mentioned explicitly if any of the provisions were to be executed immediately, like the institution of the son as “staff of old age” (assistant to an official going into partial retirement) in P. UC 32037.

“The beneficiaries of jmt-pr documents are almost always relatives and mainly children . The only known possible exception is the above-mentioned P. UC 32055. Johnson’s statement that only those persons who would not otherwise inherit received jmt-pr documents is contradicted by the standard phrase in Old Kingdom regulations relating to private funerary foundations , in which it is forbidden for the funerary personnel to sell or to give their office by jmt-pr document to anyone except a son (in the Inscription of Senenuankh, msww “children” are mentioned instead of the son): thus it was possible to write such documents even for primary heirs.

“Although jmt-pr documents are first mentioned in inscriptions of the 3rd and 4th Dynasties (e.g., Inscription A of Metjen), no document of the Old Kingdom identifies itself as an “jmt pr.” The phrase jmt pr tn “this jmt-pr document” occurring in Inscription A of Nebkauhor does not refer to the text itself but to the underlying document of which the text is but an additional provision. There exist on tomb walls, however, transcripts of documents in which property is transferred gratuitously to relatives (i.e., donations) and which therefore might be jmt-pr documents (Inscription of Wepemnofret; Inscription of Nikaura).

“From the Middle Kingdom, there are two jmt-pr documents labeled as such by their introductory formula jmt pr jrt.n NN n NN, “jmt-pr document that NN made for NN.” In P. UC 32037, the eldest son inherits the office of his father (he is introduced as his assistant already during his lifetime), while an older jmt-pr document for a first wife is canceled and a new one in favor of the children of a second wife put in its place. In P. UC 32058 a husband bequeaths his property to his wife, stipulating that she is allowed to pass it on to her children as she likes. In phrasing, these jmt-pr documents therefore resemble the documents for gratuitous property transfer of the Old Kingdom, thus strengthening the argument for the aforementioned identification, but contain additional provisions, which in the Old Kingdom seem to have been laid down in separate documents. The first known jmt- pr document drawn up in connection with a payment, most likely as a security, dates from the 12th Dynasty, and this practice seems to have continued since there is a somewhat similar case documented on the 17th Dynasty Stèle Juridique, where an jmt pr transferring the office of mayor of Elkab is used to pay back a loan from one brother to another.”

Division of an Inheritance in Ancient Egypt

family portrait

Sandra Lippert of Universität Tübingen wrote: “Through division documents, equal or unequal shares of property are allotted to several prospective heirs (usually the children of the testator). One of the earliest real divisions of property between children of the deceased is documented on Clay Tablet 3689-7 + 8 + 11 from Balat from the 6th Dynasty: of at least four sons, one receives eight water wells, one four, and two received two each. It remains unclear how this division came about: the person (Kmj) who announces the division to the authorities is neither the testator, named 6Sjw (who is probably already dead at this point), nor is he one of the inheriting children. In fact, he seems to be no relation of the family at all but rather a minor official. Therefore it cannot be determined whether the division had already been decided by the father and perhaps deposited with Kmj, or whether the children themselves wished to divide their inheritance in specie. It cannot, moreover, be excluded that the division was enacted by the administrative council to whom the clay tablet was addressed.[Source: Sandra Lippert, Universität Tübingen, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The examples for testamentary divisions from the New Kingdom show that the procedure at that time consisted of a public oral declaration of intent (r) by the testator about what items of his property should be given to whom, which was then recorded in writing. P. Ashmol. Mus. 1945.97, also known as the Will of Naunakhte, calls itself hry n Axt, “document about property”; it is a protocol of a division, although including the disinheritance of some children as well. A similar deed, cited on the occasion of a later redistribution of property among the heirs, is referred to on O. Louvre E 13156 as tp n pS, “account of division,” a term that remained in use until at least the 26th Dynasty.

“During the Late Period, possibly coinciding with the switch from abnormal hieratic to Demotic , the practice of testamental division changed from a public declaration to the setting up of individual documents for each heir, and from the allotment of specific objects to a division of the property into proportional shares, e.g., one half, one third, or the like. (It is, however, possible that simply another type of document was used if the testator wanted to allot specific objects—namely, fictitious sales documents.) Sometimes the recipients of the other shares were also mentioned. This type remained the standard for the Demotic division documents of the Ptolemaic Period (304–30 B.C.). Examples of division documents from the same testator to different beneficiaries are Papyri Bibl. nat. 216 and 217 of the 27th Dynasty, and P. BM 10575, together with the original of the transcript in P. BM 10591 verso 5.1- 5.24 of 181 B.C.. It was even possible to make the size of the share dependent on the total number of children at the time of the death of the testator.

“A remarkable exception to this pattern is P. Moscow 123 (68 B.C.), not only because it states clearly that the division is to become effective “after [the] lifetime” of the testator and “when [he is] dead” (jw.y mwt), respectively, but also because it rather resembles the New Kingdom divisions: one document, addressed to the eldest son as main heir, specifies the whole division for all co-heirs; there seem to have been no additional documents for each beneficiary.

“The division documents used as wills should not be confused with another type of division document known from the Late Period onwards that was drawn up between co-owners in order to specify their shares within a jointly owned property. This second type was also quite often connected to inheritance, since inheritance was the most common cause for joint ownership.”

Disinheritance in Ancient Egypt

Sandra Lippert of Universität Tübingen wrote: “Complete disinheritance of close relatives is not attested before the New Kingdom, although wills through which the inheritance of eldest sons was curtailed in favor of other children were possible from at least the 6th Dynasty onwards. In the Will of Naunakhte from the 20th Dynasty the testatrix specified in detail which of her children should receive none, or only a smaller share, of her property because they had neglected her. This explanation was probably not due to legal requirements, as Allam thinks, but to the feeling that some sort of justification was necessary towards the local community or the disinherited children themselves. [Source: Sandra Lippert, Universität Tübingen, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Requirements for the designated heirs: “There seems to have been no legal objection against appointing someone as heir who was not a blood relative or an adopted child; indeed at least in the New Kingdom there was a law, cited in P. Turin 2021 + P. Geneva D 409 col. 2.11 as [jmm jr s] nb Abt.f m Axt.f “Let every man do what he wants with his property,” and on the Third Intermediate Period statue Cairo CG 42208 c, 14 as jmm jr s nb sxr n jSt.f “Let every man dispose (freely) of his property.” However, in cases where a non-blood relation was established as heir, it was usually the wife: in P. UC 32058 a husband bequeaths the property that he himself had inherited from his brother to his wife by means of an jmt-pr document. In P. UC 32037, a similar jmt-pr document for the mother of the eldest son was canceled and replaced by one favoring the children of another wife, probably because by then the first wife had died or had been divorced. Both documents date to the Middle Kingdom. It is noteworthy that in the two similar cases of wives being established as heirs from the New Kingdom this was effected not by jmt-pr document but through adoption, while in the Late and Ptolemaic and Roman Periods fictitious sales with burial obligation or special clauses within marriage documents were used.

“The only known jmt-pr document not drawn up for a blood relation seems to have been P. UC 32055, concerning a priestly office as security for a loan; from the fragmented text it does not appear which, if any, kinship relation there was between both parties.”

Marriage and Inheritance

Nakht and family outing

Sandra Lippert of Universität Tübingen wrote: “Benefits for the spouse: The division of matrimonial property between the spouses with one third belonging to the wife—first attested in the 17th Dynasty, attested several times in the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.), and commonly mentioned in Late Period (712–332 B.C.) and Ptolemaic marriage documents—has often been seen as a matter of inheritance. In reality, however, the wife did not inherit a third of her husband’s property. Rather, she was endowed with it already during her husband’s lifetime, as can be seen from the fact that the third also fell to her in the case of divorce. Since the attestation of the one-third/two-thirds division far predates the earliest marriage documents and is there given as a well-known fact, it can be safely assumed that it was not dependent upon individual arrangements but legally binding from at least the New Kingdom onwards, as is also suggested by the peculiar phrasing of O. DeM 764, in which this division is set up as a general rule with the typical conditional protasis and injunctive or future apodosis structure of later law texts: “If the children are small, the property will constitute three parts: one for the children, one for the man, one for the woman. If he (i.e., the man) provides for the children, give to him the two thirds of all property, the one third being for the woman”. In Late and Ptolemaic and Roman Period marriage documents, the wife could be allotted to inherit larger parts or even all of her husband’s property, but her right of disposal was usually restricted so that the property would after her death fall automatically to the children. [Source: Sandra Lippert, Universität Tübingen, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Benefits for the children: “As seen above, some jmt-pr documents of the Middle and New Kingdoms, and some marriage documents of the Late and Ptolemaic and Roman Periods through which inheritance was allotted to a wife, state that all property is ultimately to fall to the children. In certain types of marriage documents that became current from the 26th/27th Dynasties onwards, the inheritance rights of the children from the marriage in question were established, sometimes even before the children were born. Often it was stressed that the firstborn son of this marriage would be counted as “eldest son” in the sense of the legal order of succession and therefore be the main or even sole heir: the phrasing “Your eldest son is my eldest son [among the children you will bear to me] . . .” was often extended to “. . . the master of all that I possess and will acquire.” In other documents of this type, all children (or occasionally only the sons) were instituted as heirs of the paternal property. If a man who had made a marriage settlement of the above-mentioned kind married a second time (either because he had divorced his first wife or because she had died), he could only draw up another marriage settlement if the first wife and/or his eldest son agreed to it in writing because he had already pledged his property as security for the maintenance of his first wife and promised it as inheritance to the wife and/or the children from his first marriage. This is explicitly stated in a law cited by the judges of the so-called Siut trial.”

Objects of Inheritance

Sandra Lippert of Universität Tübingen wrote: “The kind of property that could be bequeathed included real estate, movables, and certain offices with the benefices belonging to them. Since the possibility of free disposal either through sale, donation, or bequeathing was the main criterion for personal property in a society where, ultimately, everything belonged to the king, the declaration that basically all types of personal property could be bequeathed and inherited is a circular statement. By examining at what period which types of property appear as objects of inheritance and by which means they were transferred, we can, however, learn more about the development of personal property. [Source: Sandra Lippert, Universität Tübingen, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Real estate (buildings and land): Already in the Old Kingdom (2649–2150 B.C.), real estate was an object of inheritance. In the Inscription of Metjen A, Metjen recounts how his mother made an jmt-pr document for her children, most likely concerning fields, since Metjen either received 50 aurourai out of this or gave them to her for that purpose. Real estate in the Old Kingdom usually included personnel who, however, should not be labeled as slaves since these people could not be sold independently from the land to which they belonged.

“Moveables: Although the main focus of documents of inheritance was usually on real estate, items of lesser value, such as furniture and household implements, were occasionally mentioned, especially if there seems to have been no other property. From the Middle Kingdom onwards, there are attestations that slaves could be inherited.

“Offices and appurtenant income: Not all offices were inheritable, and even those that were usually held restrictions either as to the way in which they were bequeathed and/or to whom; with higher offices, royal (or, during the Third Intermediate Period, divine) approval was also necessary. During the Old Kingdom, inheritability of offices is attested for priestly functions of private funerary cults that, in the regulations, are usually stipulated to fall to the eldest son alone. The standard phrasing for this is “I do not give power to sell or to bequeath by jmt pr to anyone except the eldest son”. Rarely “children” in general is substituted for “eldest son”. It remains unclear whether this actually means that they could not be conveyed in any other way (i.e., through legal succession). For priestly offices at royal funerary temples, and supposedly for offices in the royal administration as well, their inheritability seemingly had to be granted in writing by the royal chancellery, most likely in consequence of a royal decree.

“From the Middle Kingdom onwards, occasionally also state and temple offices such as the mayorship of Elkab or the office of Second Prophet of Amun appear as objects of inheritance, usually through jmt pr. Perhaps this was in fact a legal requirement, because, at least until the early New Kingdom, it meant that the bureau of the vizier had to give its agreement. The incomes of funerary priests (choachytes) for their sevices at private tombs appear quite often in inheritance documents from the Late Period onwards.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024