Home | Category: People, Marriage and Society

CHILDREN, GAMES AND TOYS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

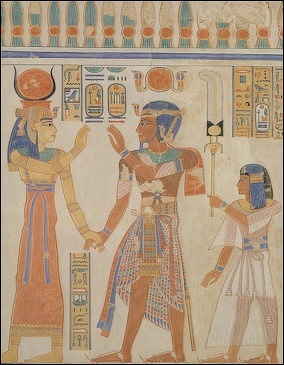

Ramses III and Prince Amenherkhepesef before Hathor

The ancient Egyptians revered children and children were a valued part of ancient Egyptian society. Examples of child abuse are extremely rare. By contrast, Joseph Castro of Live Science wrote, “though Romans loved their kids immensely, they believed children were born soft and weak, so it was the parents' duty to mold them into adults. They often engaged in such practices as corporal punishment, immobilizing newborn infants on wooden planks to ensure proper growth and routinely bathing the young in cold water as to not soften them with the feel of warm water.” [Source: Joseph Castro, Live Science, May 28, 2013]

There is evidence that Egyptian children played marbles 5000 years ago ( rounded semiprecious stones buried with a child around 3000 B.C., in Nagada Egypt). Marbles and knucklebones from dogs and sheep were used by adults in divining rituals. Rock, Scissors, Paper was played by the Egyptians and Romans. An Egyptian painting dated to 2000 B.C. shows a finger game like it being played.

Children in ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome made hoops from dried and stripped grapevines and rolled them down the street with a rod. Rattles made with dried gourds filled with clay balls or pebbles were discovered in children's tombs dated at 1360 B.C. They were shaped like birds, pigs and bears. Rattles were also used in ancient rituals to scare off evil spirits. The earliest dolls were images and idols of gods. Playing with idols was considered sacrilegious so the first true dolls were model or ordinary people played with by children. Early females dolls had breasts and male dolls had penises.

Young people in ancient Egypt had bows and arrows with which they might shoot at targets made of the skin of some animal, or they had a game they played similar to one of our own, in which by a powerful throw a point was driven obliquely into a block of wood, whilst the opponent had to drive it out again with his own point. There was also a game with two hooks and a ring,' and many others, about which we can ascertain nothing from the monuments. In one old game which concentric circles were drawn on the ground. " Each of the players put a stone inside the circles, but what was exactly the object of the game or how it was played we cannot determine, as we only possess one single picture in which it is represented. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN EDUCATION africame.factsanddetails.com

FAMILIES IN ANCIENT EGYPT: HOUSEHOLDS, PARENTS AND CHILDREN africame.factsanddetails.com ;

FAMILY RELATIONS AND KINSHIP IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Childhood in Ancient Egypt” by Amandine Marshall and Colin Clement (2022) Amazon.com;

“Kinship and Family in Ancient Egypt: Archaeology and Anthropology in Dialogue”

by Leire Olabarria (2020) Amazon.com;

“Households in Context: Dwelling in Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt” by Caitlín Eilís Barrett and Jennifer Carrington (2024) Amazon.com;

“Private Life in New Kingdom Egypt” by Lynn Meskell Amazon.com;

“The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt: A Genealogical Sourcebook of the Pharaohs” Amazon.com;

“Women in Ancient Egypt” by Gay Robins (1993) Amazon.com;

“Daughters of Isis: Women of Ancient Egypt” by Joyce Tyldesley (1994) Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Herodotus on Psammetichus’s Experiment on Language and Children

Psammetichus — better known today as Psamtik I — was the first pharaoh of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt. He ruled from the city of Sais in the Nile delta between 664–610 B.C. The great Greek historian Herodotus (484 – c. ... 425 B,C.) wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “Now before Psammetichus became king of Egypt,1 the Egyptians believed that they were the oldest people on earth. But ever since Psammetichus became king and wished to find out which people were the oldest, they have believed that the Phrygians were older than they, and they than everybody else. Psammetichus, when he was in no way able to learn by inquiry which people had first come into being, devised a plan by which he took two newborn children of the common people and gave them to a shepherd to bring up among his flocks. He gave instructions that no one was to speak a word in their hearing; they were to stay by themselves in a lonely hut, and in due time the shepherd was to bring goats and give the children their milk and do everything else necessary. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“Psammetichus did this, and gave these instructions, because he wanted to hear what speech would first come from the children, when they were past the age of indistinct babbling. And he had his wish; for one day, when the shepherd had done as he was told for two years, both children ran to him stretching out their hands and calling “Bekos!” as he opened the door and entered. When he first heard this, he kept quiet about it; but when, coming often and paying careful attention, he kept hearing this same word, he told his master at last and brought the children into the king's presence as required. Psammetichus then heard them himself, and asked to what language the word “Bekos” belonged; he found it to be a Phrygian word, signifying bread. Reasoning from this, the Egyptians acknowledged that the Phrygians were older than they. This is the story which I heard from the priests of Hephaestus'2 temple at Memphis; the Greeks say among many foolish things that Psammetichus had the children reared by women whose tongues he had cut out. 3.

Health Issues Involving Children

a toy Despite the fact that children played a central part in the lives of ancient Egyptians, pregnant women are seldom depicted. One of the few examples depicts queen Ahmose in the Deir el-Bahri divine birth sequence. In Sudan, a skeleton of an adult Nubian female was found with baby's skeleton lying across her ankles

Joyce M Filer wrote for the BBC: “Many women died as young adults, and childbirth and associated complications may well have been the cause.Although Egyptians 'experimented' with contraception-using a diverse range of substances such as crocodile dung, honey and oil-ideally they wanted large families. Children were needed to help with family affairs and to look after their parents in their old age. This would have led to women having numerous children, and for some women these successive pregnancies would have been fatal. Even after giving birth successfully, women could still die from complications such as puerperal fever. It was not until the 20th century that improved standards of hygiene during childbirth started to prevent such deaths. [Source: Joyce M Filer, BBC, February, 17, 2011 |::|]

“People are open to the greatest health risks during infancy and early childhood, and in Egypt and Nubia there was a high infant mortality rate. During the breastfeeding period the baby is protected from infections by ingesting mother's milk, but once weaned onto solid foods the chances of infection are high. Consequently many infants would have died of diarrhoea and similar disorders caused by food contaminated by bacteria or even intestinal parasites. In some ancient Egyptian and Nubian cemeteries at least a third of all burials are those of children, but such illnesses rarely leave telltale markers on the skeleton, so it is hard to know the exact numbers affected.” |::|

Mummies Appear to Show Many Ancient Egyptian Children Had Anemia

An examination of 21 ancient Egyptian mummified children revealed that one-third of them had the blood disorder of anemia, which is often connected with medical problems such as malnutrition and growth defects. In a study published April 13, 2023 in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, an international team of researchers used full body CT (computed tomography) scans to examine the mummies of children who had died between the ages of 1 and 14 and determined they had anemia based on abnormal growth in the mummies' skulls and arm and leg bones. [Source: Hannah Kate Simon, Live Science, May 16, 2023]

Hannah Kate Simon wrote in Live Science: Seven of the mummies, or 33 percent of those studied, showed signs of anemia in the form of thickened skull bones, the researchers found. Today, anemia is thought to affect 40 percent of children under the age of 5 years old globally, according to the World Health Organization. This research on anemia in ancient Egypt "may shed light on ancient societies' health issues, dietary inadequacies, and social standards," Sahar Saleem, head and professor of radiology at Cairo University and a member of the Egyptian Mummy Project, told Live Science. Saleem was not involved in the study.

This study, possibly the first of its kind, included child mummies from various parts of Egypt dating as early as the Old Kingdom (third millennium B.C.) to the Roman Period (fourth century A.D.).Indigo Reeve, a bioarchaeologist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland who was not involved in the study, defined anemia as "a lack of healthy red blood cells or hemoglobin." This condition can stem from a variety of causes, including dietary deficiencies, inherited disorders and infections, which can all lead to intestinal blood loss and poor absorption of nutrients, Reeve told Live Science. Anemia typically causes fatigue and weakness, but it can also cause irregular heartbeat and can be life-threatening depending on the type and severity, she added.

Childhood cases of anemia can cause the expansion of some bone marrow, which is found at the center of most bones, which can lead to odd and abnormal bone growth, such as the thickening of the cranial vault, the part of the skull that holds the brain, Reeve explained. Porous lesions can also appear on bones, especially on the skull, which can cause further medical problems.

The study uncovered some of these anemia-related issues in the mummified children. In one of the seven cases with thickened cranial vaults, a 1-year-old boy showed cranial signs of thalassemia, an inherited blood disorder that can cause mild to severe anemia due to reduced hemoglobin production; other symptoms of thalassemia can include inadequate and unusual bone growth and an increased risk of infections, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine. The boy also had an enlarged tongue and a condition known as "rodent facies," which is an abnormal growth of the cheekbones and an elongated skull. This boy's severe anemia, compounded with other difficulties, likely caused his death, the researchers theorized.

It's unclear how these ancient children came to have anemias, but the disorder can be caused by malnutrition, iron deficiency in pregnant mothers, chronic gastrointestinal issues and bacterial, viral or parasitic infections, all of which are thought to have been prevalent in ancient Egypt, the researchers said.However, the study's small sample of 21 child mummies is not representative of an entire population or time period, the researchers noted. Further, the CT scans "produced blurry images due to low resolution that prevented interpretation" of additional signs of anemia, Saleem said.

Child Rearing in Ancient Egypt

toy mummies

The mother had the charge of the child during its infancy, she nursed it for three years and carried it on her neck," — this corresponds exactly to the custom of the modern Egyptians. During the first years of their childhood the boys, and very often the girls also,' went nude. A grandson of King Chufu was content with nature's own costume even when he was old enough to be a “writer in the house of books," i.e. went to school. ' Based on tomb imgaes, many children wore the short plaited lock on the right side of the head, following the example of the youthful god Horus, who was supposed to have worn this side-lock. I cannot say whether all children of a certain age wore this lock, or whether originally it was worn as a mark of distinction by the heir, as the pictures of the Old Kingdom would lead us to believe." It is also uncertain how long it was worn, in one poem the “royal child with the lock “is a “boy of ten years old; “on the other hand, the young king, Merenre (Dynasty VI.), wore the lock all his life, and the royal sons of the New Kingdom certainly wore it even in their old age'. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The years of childhood, the four years in which each was a “wise little one," i.e. a good child, were spent as they are everywhere all over the world. The toys, such as the naughty crocodile, the good little man who would jump, and the beautiful dolls which moved their arms,"' show us that the little Egyptian girls were just like other children.

For some of the elite, based on tomb images, there were flowers also and pet birds in the nursery; and we find that Sechentchak, the above-mentioned little “writer in the house of books," was not ashamed to take a poor hoopoo about with him.' Boyhood, the time of education, followed the period of childhood, which under the New Kingdom closed with the fourth year." The school boy had also his proper costume, which in old times seems to have consisted of a girdle only. The Egyptians realised that it was a father's duty to superintend the education of their children, as we learn from the favorite dialogues between a father and a son contained in the didactic literature.

Even at this tender age, the children of the upper class were frequently sent away from home; they were either brought up in the palace with the royal children, or they had to enter the school belonging to one of the government departments to prepare for their official career." Besides the purely scientific instruction of which we shall have to treat in the 14th chapter, and the gymnastic exercises such as swimming;' the school-course consisted above all in the teaching of ethics, practical philosophy, and good manners.

Advise on Child Rearing in Ancient Egypt

From a book edited probably in the time of the Middle Kingdom, but written under king 'Ess'e (Dynasty V),we learn how a father ought to instruct his son: “Be not proud of thine own learning, but do thou take counsel with all, for it is possible to learn from all. Treat a venerable wise man with respect, but correct thine equal when he maintains a wrong opinion. Be not proud of earthly goods or riches, for they come to thee from God without thy help. Calumnies should never be repeated: messages should be faithfully delivered. In a strange house, look not at the women; marry; give food to thy household; let there be no quarrelling about the distribution. For the rest, keep a contented countenance, and behave to thy superiors with proper respect, then shalt thou receive that which is the highest reward to a wise man; the “princes who hear thee shall say: ' How beautiful are the words which proceed out of his mouth.' " [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

A similar instruction of the time of the New Kingdom gives still more detailed advice. Be industrious, “let thine eyes be open, lest thou become a beggar; for the man that is idle cometh not to honour." ' Be not importunate nor indiscreet; “enter not uninvited into the house of another; if he bids thee enter thou art honoured. Look not around, look not around in the house of another. If thine eye see anything, be silent about it, and relate it not outside to others, lest if it be heard, it become to thee as a crime worthy of death." Speak not too much, for men are deaf to the man of many words; be silent rather, then shalt thou please, therefore speak not.'' Before all things guard thy speech, for “a man's ruin lies in his tongue." Man's body is a storehouse, full of all manner of answers. Choose therefore the right one and speak well, and let the wrong answer remain imprisoned in your body." “lchavc with propriety at meals, and “be not greedy to fill thy body/ Eat not bread whilst another standeth by, unless thou shalt lay his hand on the bread also. . . . One is poor, another is rich, but bread remains to him that is generous. He that was rich in the year that is past, may even in this year become a vagrant." Never forget to be respectful, and “do not sit down whilst another stands, who is older than thou, or who holds a higher office than thou dost." '

These rules for good conduct are enough to show how much the higher classes thought of good manners, and the strict formulae of letter writing, though they varied according to the rank and position of the correspondents, show us that the Egyptians of the New Kingdom were lovers of strict etiquette.

Instruction of Ptah-Hotep (2200 B.C.) on Being a Good Son

The Instruction of Ptahhotep ( c. 2200 B.C.) reads: “A son who attends is like a follower of Horus; he is happy after having attended. He becomes great, he arrives at dignity, he gives the same lesson to his children. Let none innovate upon the precepts of his father; let the same precepts form his lessons to his children. "Verily," will his children say to him, "to accomplish what you say works marvels." Cause therefore that to flourish which is just, in order to nourish your children with it. If the teachers allow themselves to be led toward evil principles, verily the people who understand them not will speak accordingly, and that being said to those who are docile they will act accordingly. Then all the world considers them as masters and they inspire confidence in the public; but their glory endures not so long as would please them. Take not away then a word from the ancient teaching, and add not one; put not one thing in place of another; beware of uncovering the rebellious ideas which arise in you; but teach according to the words of the wise. Attend if you wish to dwell in the mouth of those who shall attend to your words, when you have entered upon the office of master, that your words may be upon our lips . . . and that there may be a chair from which to deliver your arguments.

“Let your thoughts be abundant, but let your mouth be under restraint, and you shall argue with the great. Put yourself in unison with the ways of your master; cause him to say: "He is my son," so that those who shall hear it shall say "Praise be to her who has borne him to him!" Apply yourself while you speak; speak only of perfect things; and let the great who shall hear you say: "Twice good is that which issues from his mouth!"

“Do that which your master bids you. Twice good is the precept of his father, from whom he has issued, from his flesh. What he tells us, let it be fixed in our heart; to satisfy him greatly let us do for him more than he has prescribed. Verily a good son is one of the gifts of Ptah, a son who does even better than he has been told to do. For his master he does what is satisfactory, putting himself with all his heart on the part of right. So I shall bring it about that your body shall be healthful, that the Pharaoh shall be satisfied with you in all circumstances and that you shall obtain years of life without default. It has caused me on earth to obtain one hundred and ten years of life, along with the gift of the favor of the Pharoah among the first of those whom their works have ennobled, satisfying the Pharoah in a place of dignity. It is finished, from its beginning to its end, according to that which is found in writing.”

Children and Upbringing in the Harem

Silke Roth wrote: “Another key function of the harem was the upbringing of royal and elite children. From the Old Kingdom on, a pr mna(t), a “house of education” or “house of the nursery,” is attested as place of learning and from the Middle Kingdom a kAp. The latter can be identified as part of the royal private quarters or the jpt nswt. It is possible that a number of kAp existed, which were assigned to particular royal children. 4bAw nswt, “instructors of the king,” and mna(t) nswt, “tutors” or “wet nurses of the king” were responsible for raising and educating the royal children. [Source: Silke Roth, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“The sons and daughters of distinguished officials could be raised together with royal children, thus creating a close personal bond between the future ruling class and the successor to the throne. Later in their careers they bore titles such as sbAtj nswt or sDtj(t) nswt, “foster son/daughter of the king”; Xrd(t) n kAp, “child of the kAp”; and sn(t) mna n nb tAwj, “foster brother/sister of the Lord of the Two Lands”.

Wet nurses were often senior harem members. A drawing found in a chapel for King Tutankhamun showed a wet nurse with the young pharaoh. It bore the inscription: "royal nurse who suckled the boy of the god (pharaoh) and who was favored by the king."

Ancient Egyptian Teenager Buried with Exquisite Jewelry and Leather Shoes

In April 2020, Spanish and Egyptian archaeologists announced that they uncovered a teenager who was only 15 or 16 years old when she died during the 17th dynasty (1580 B.C. to 1550 B.C. along with one of the world’s oldest pairs of leather shoes, José Galán, director of the archaeological mission, said. Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science: The girl's mummy was resting on its right side in the Draa Abul Naga necropolis on Luxor's West Bank, according to Ahram Online, an Egyptian newspaper. Though the mummy had deteriorated over the millenia, restoration returned her jewelry to pristine condition. This included two spiral earrings coated with a thin metal leaf — possibly of copper — in one of her ears, as well as two rings on her fingers and four necklaces draped around her neck. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science published April 29, 2020]

One ring was fashioned out of bone, while the other was made of metal and held an embedded blue glass bead with string wrapped around it. The four necklaces were tied together with a glazed ceramic, or "faience" clip. Like the rings, each necklace was unique. One 27.5-inch-long (70 centimeters) necklace was made of round beads that alternated between dark and light blue faience, and another necklace, measuring 24.4 inches long (62 cm) necklace, had green faience and glass beads.

The third necklace was a treasure even by today's standards; the 24-inch-long (61 cm) necklace had 74 pieces, including beads of amethyst; a brownish-red gemstone called carnelian; amber; blue glass; and quartz, according to the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. It also sported two scarabs, including one showing Horus (a god depicted as a falcon) and five faience amulets. Finally, the fourth necklace was designed with several strings of faience beads, which were knotted together at both ends with a ring.

The 5.7-foot-long (1.75 meters) coffin was carved out of a sycamore tree trunk. At the time of the teenager's death, it had been whitewashed and painted in red, according to Ahram Online. The archaeologists also found a miniature mud-made coffin that was still tied together with a string, near the teenager's mummy. When they opened this small coffin, the archaeologists found a wooden funerary figurine, known as an ushabti, wrapped in four linen bandages. The figurine and one of the bandages were marked in hieratic (an ancient Egyptian cursive text) with the name of the owner: "The Osiris, Djehuty." The excavation team also found a pair of leather sandals and leather balls tied together with a string, which also dated to the 17th dynasty. "The sandals are in a good state of preservation, despite being 3,600 years old," Galán said. These shoes were dyed red and engraved with images of the god Bes, the goddess Taweret, a pair of cats, an ibex and a rosette, according to Ahram Online. Based on the sandals' size and decorations, it's likely that they belonged to a woman, Galán said. The balls were used by women for sport or for choreographed dancing, according to images of daily life found in the Beni Hassan tombs from the Middle Kingdom (2040 B.C. to 1782 B.C.) of Egypt.

Mummy of Ancient Egyptian Teenager Shows She Died Giving Birth to Twins

In January 2024, scientists revealed that an ancient Egyptian mummy with a fetus tucked between its legs and another lodged inside the chest cavity was a teenager who died while giving birth to twins. Sascha Pare wrote in Live Science: When archaeologists excavated and unwrapped the mummy in 1908, they discovered the bandaged body of a fetus and the remains of a placenta wedged between the girl's legs. Field notes from the time reveal the researchers concluded the fetus was related to the mummified female — a girl between 14 and 17 years old who lived in ancient Egypt sometime between the Late Dynastic (from around 712 to 332 B.C.) and Coptic period (between A.D 395 and 642). Researchers incised the mother's abdomen and found the fetus' skull stuck in the birth canal, indicating the girl had died from complications during childbirth. [Source: Sascha Pare, Live Science January 5, 2024

But it wasn't until a century later that researchers discovered a second fetus, this time mysteriously lodged in the girl's chest. "This is the first mummy of its kind discovered," said study lead author Francine Margolis, a U.S.-based independent archaeologist. While there are many known burials of women who died in childbirth in the archaeological record, "there has never been one found in Egypt," Margolis told Live Science.

Margolis first studied the mummy excavated in 1908 while writing her master's thesis in anthropology at George Washington University (GWU) in Washington, D.C. on female pelvic morphology in 2019. "I CT scanned her to obtain her pelvic measurements," Margolis said. "That is when we discovered the second fetus." The 3D images showed that the remains of a fetus, which no previous records mentioned, had become lodged in the girl's chest. Margolis and David Hunt, co-author of the new study and an anthropologist at GWU, X-rayed the mummy to obtain a clearer picture of the fetal remains. "When we saw the second fetus we knew we had a unique find and a first for ancient Egyptian archaeology," Margolis said.

For the study, published December 21, 2023 in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, Margolis and Hunt found that the girl died in labor after the head of the first fetus became trapped in the birth canal, she said. The head of a fetus exiting the womb during childbirth is usually tucked to its chest to enable passage through the pelvis, according to the study. The researchers think that in this case, the fetus' head was untucked in a position that was too broad to get through and became stuck. Results from the 2019 analysis showed the mother stood around 5 feet tall (1.52 meters) and weighed between 100 and 120 pounds (45 to 55 kilograms). Her small size and young age may have contributed to her unsuccessful delivery of the twins, the researchers noted in the new study.

Was Child Labor Used to Build the Ancient Egyptian City of Amarna?

There is evidence that a ‘disposable’ workforce of children and teenagers provided much of the labour to build Amarna — the great capital city of Akhenaten (1353-1336 B.C.), the Pharaoh who tried to introduce monotheism to Egypt. Mary Shepperson wrote in The Guardian: “Amarna came and went in an archaeological moment. It rose and fell with Akhenaten and his religious reformation, under which Egypt’s ancient pantheon of gods was briefly usurped by the worship of a single solar deity; the Aten. Between 2006 and 2013 I was lucky enough to work for the Amarna Project on an excavation which aimed to recover four hundred individuals from a large cemetery behind the South Tombs cliffs, estimated to contain around six thousand badly looted burials. The study of these burials and their human remains has opened a new research window on life and death in the lower echelons of Egyptian society. They paint a picture of poverty, hard work, poor diet, ill-health, frequent injury and relatively early death. [Source:Mary Shepperson, University of Liverpool, The Guardian, June 6, 2017]

“In other respects the South Tombs Cemetery remains were fairly in line with expectations. There were modest variations in the wealth and style of burial, there was a fairly even mix of male to female individuals, and the age distribution showed the usual pattern for ancient populations; high infant mortality giving way to fewer deaths as children survive into early adulthood, with the death rate then rising again as adults succumb to illness, childbirth, injuries and age. This was all important and highly interesting, but not particularly unusual.

“In 2015 we began excavating another non-elite cemetery in a wadi behind a further set of courtiers’ tombs at the northern end of the city, and here the tale takes a stranger turn. As we started to get the first skeletons out of the ground it was immediately clear that the burials were even simpler than at the South Tombs Cemetery, with almost no grave goods provided for the dead and only rough matting used to wrap the bodies.

“As the season progressed, an even weirder trend started to become clear to the excavators. Almost all the skeletons we exhumed were immature; children, teenagers and young adults, but we weren’t really finding any infants or older adults. Our three excavation areas were far apart, spaced across the length of the cemetery, but comparing notes all three areas were giving the same result. This certainly was unusual and not a little bit creepy.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Did children build the ancient Egyptian city of Amarna? By Mary Shepperson, in The Guardian theguardian.com

Earliest — But Rare — Case of Child Abuse Discovered in Egyptian Cemetery

In May 2013, researchers, headed by Sandra Wheeler, a bioarchaeologist at the University of Central Florida, announced they had found 2- to 3-year-old child from the Kellis 2 Romano-Christian-period cemetery in Dakhleh Oasis, Egypt that showed evidence of physical child abuse, making it the earliest documented case of child abuse in the archaeological record, and the first case ever found in Egypt, researchers say. [Source:Joseph Castro, Live Science, May 28, 2013]

Joseph Castro wrote in Live Science; The cemeteries in the oasis allow scientists to take a unique look at the beginnings of Christianity in Egypt. In particular, the so-called cemetery, which is located in the Dakhleh Oasis town of Kellis (southwest of Cairo), reflects Christian mortuary practices. For example, "instead of having children in different places, everyone is put in one place, which is an unusual practice at this time," Wheeler told LiveScience. Dating methods using radioactive carbon from skeletons suggest the cemetery was used between A.D. 50 and A.D. 450.

When the researchers came across the abused toddler — labeled "Burial 519" — in Kellis 2, nothing seemed out of the ordinary at first. But when Wheeler's colleague Tosha Duprasbegan brushing the sand away, she noticed prominent fractures on the child's arms. "She thought, 'Whoa, this was weird,' and then she found another fracture on the collarbone," Wheeler said. "We have some other kids that show evidence of skeletal trauma, but this is the only one that had these really extreme fracture patterns."

The researchers decided to conduct a series of tests on Burial 519, including X-ray work, histology (microscopic study of tissues) and isotopic analyses, which pinpoint metabolic changes that show when the body tried to repair itself. They found a number of bone fractures throughout the body, on places like the humerus (forearm), ribs, pelvis and back. Whereas no particular fracture is diagnostic of child abuse, the pattern of trauma suggests it occurred. Additionally, the injuries were all in different stages of healing, which further signifies repeated nonaccidental trauma. One of the more interesting fractures was located on the child's upper arms, in the same spot on each arm, Wheeler said. The fractures were complete, broken all the way through the bone — given that children are more flexible than adults, a complete break like that would have taken a lot of force. remains of toddler with evidence of child abuse in ancient egypt cemetery.

After comparing the injury with the clinical literature, the researchers deduced that someone grabbed the child's arms and used them as handles to shake the child violently. Other fractures were also likely caused by shaking, but some injuries, including those on the ribs and vertebrae, probably came from direct blows. The archaeologists aren't sure what ultimately killed the toddler. "It could be that last fracture, which is the clavicle fracture," Wheeler said, referring to the collarbone. "Maybe it wasn't a survivable event."

Of the 158 juveniles excavated from the Kellis 2 cemetery, Burial 519 is the only one showing signs of repeated nonaccidental trauma, suggesting child abuse wasn't something that occurred throughout the community. The uniqueness of the case supports the general belief that children were a valued part of ancient Egyptian society. By contrast, though Romans loved their kids immensely, they believed children were born soft and weak, so it was the parents' duty to mold them into adults. They often engaged in such practices as corporal punishment, immobilizing newborn infants on wooden planks to ensure proper growth and routinely bathing the young in cold water as to not soften them with the feel of warm water. "We know that the ancient Egyptians really revered children," Wheeler said. "But we don't know how much Roman ideas filtered into Egyptian society," she added, suggesting that the unique child abuse case may have been the result of Roman influence.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024