Home | Category: Late Stone Age and Copper and Bronze Age / Canaanites and Early Biblical Peoples / Canaanites and Early Biblical Peoples

CANAANITE LANGUAGE

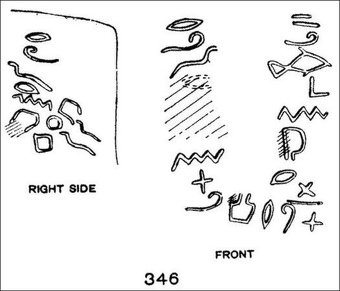

Drawings of the first known Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions, as published in "The Egyptian Origin of the Semitic Alphabet", by Alan H Gardiner.

The Canaanites are broadly defined to include the Hebrews (including Israelites, Judeans and Samaritans), Amalekites, Ammonites, Amorites, Edomites, Ekronites, Hyksos, Phoenicians (including the Carthaginians), Moabites, Suteans and sometimes the Ugarites. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Canaanite languages are one of three subgroups of the Northwest Semitic languages, with the others being Aramaic and Amorite. These closely related languages, sometimes viewed as diaelects, originate in the Levant and Mesopotamia, and were spoken by the ancient Semitic-speaking peoples of an area that stretched from Israel and Palestine to southwestern Turkey (Anatolia), western and southern Mesopotamia and the northwestern part of Saudi Arabia.

The Canaanite languages were widely spoken everyday languages in their region until at least the A.D. 2nd century. Hebrew is the only living Canaanite language today. It remained in continuous use by many Jews well into the Middle Ages and up to the present day as mainly as a liturgical language.

RELATED ARTICLES:

CANAANITES: WHO THEY WERE, THEIR CITIES AND DEPICTIONS OF THEM IN THE BIBLE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITES: HISTORY, ORIGINS, INVASIONS, BATTLES factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITE RELIGION: TEMPLES, OFFERINGS, RITUALS AND CULTS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITE GODS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITE TOMBS AND BURIAL PRACTICES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITE HOUSES, BUILDINGS AND SETTLEMENTS factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITE LIFE: TOOLS, EVERYDAY ITEMS AND MONEY africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITE FOOD, DRINK, DRUGS, CLOTHES, JEWELRY africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITE ART, CRAFTS, MUSIC AND GAMES africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Dawn of Israel: A History of Canaan in the Second Millennium BCE”

by Lester L. Grabbe Amazon.com ;

“The Canaanites: Their History and Culture from Texts and Artifacts” by Mary Ellen Buck

Amazon.com ;

“The Lost World of the Israelite Conquest: Covenant, Retribution, and the Fate of the Canaanites” by John H. Walton and J. Harvey Walton Amazon.com ;

“Stories from Ancient Canaan” by Michael D. Coogan and Mark S. Smith Amazon.com ;

“Israelite Religions: An Archaeological and Biblical Survey”

by Richard S. Hess Amazon.com ;

“Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan” by John Day , Andrew Mein, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Curse of Canaan” by Eustace Clarence Mullins Amazon.com ;

“The Conquest of Canaan” by Jessie Penn-Lewis Amazon.com ;

“Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, Philistines, and Early Israel, 1300-1100 B.C.E.” by Ann E Killebrew Amazon.com ;

“Hazor: Canaanite Metropolis:Israelite City” by Amnon Ben-Tor Amazon.com ;

“The Bible Unearthed” by I. Finkelstein and N. Asher Silberman Amazon.com ;

“Archaeology of the Bible: The Greatest Discoveries From Genesis to the Roman Era”

by Jean-Pierre Isbouts Amazon.com ;

“Unearthing the Bible: 101 Archaeological Discoveries That Bring the Bible to Life” Amazon.com ;

“Zondervan Handbook of Biblical Archaeology: A Book by Book Guide to Archaeological Discoveries Related to the Bible” by J. Randall Price and H. Wayne House Amazon.com ;

“NIV, Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible (Context Changes Everything) by Zondervan, Craig S. Keener Amazon.com ;

“Egypt, Canaan and Israel in Ancient Times” by Donald Redford Amazon.com ;

“Oxford Companion to the Bible” by Bruce M. Metzger and Michael David Coogan Amazon.com ;

“HarperCollins Atlas of Bible History”

by James B. Pritchard Amazon.com ;

“Historical Atlas of the Holy Lands” by K. Farrington Amazon.com

World’s Oldest Alphabetic Written Languages

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: General scholarly agreement maintains that our oldest examples of alphabetic writing comes from the Sinai Peninsula and Egypt and can be dated to the nineteenth century BCE. These important inscriptions were discovered in 1998 in western Egypt and were published by a team led by Yale Egyptologist John Darnell. It’s clear that at some point alphabetic writing moved from Egypt to ancient Palestine but — until the early the 2020s — the earliest examples of alphabetic writing from the Levant were dated to the thirteenth or twelfth century BCE, some six hundred years after the Egyptian examples. How and under what circumstances the alphabet was moved from Egypt to Israel was anyone’s best guess. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, April 25, 2021]

Though there is considerable debate, some scholars hypothesized that the alphabet was transmitted in the twelfth century BCE, a period when there was intensive mining by Egyptians at Serabit el-Khadim in the Sinai desert. Graffiti produced by enslaved prisoners of war at the mines and found at the site led some to argue that the proto-semitic alphabet developed during a period in which Egyptians dominated the region. Prior to the 14th century BCE there were no alphabetic Palestinian inscriptions. The debate was complicated by the fact that scholars often disagreed about whether or not inscriptions were truly alphabetic (as opposed to pictographic) and to what period, exactly, they should be dated. There was a general sense, however, that the development of the alphabet should be tied to a period of Egyptian dominance.

See Separate Article: WORLD’S OLDEST ALPHABETS AND ALPHABETIC WRITTEN LANGUAGES africame.factsanddetails.com

Canaanite — the World’s Oldest Alphabetic Written Language?

The written language of the Canaanites preceded Latin, making it the oldest written language with an alphabet in history, as it was the "first alphabet in the world from which most of the modern alphabets, including the Latin alphabet, descend," Daniel Vainstub, an epigrapher at Ben-Gurion University in Israel, told Live Science. [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, November 14, 2022]

According to Smithsonian magazine: The Canaanite writing system generally agreed to have emerged between 1900 and 1400 B.C. — offered a clear improvement in user-friendliness compared with earlier pictorial scripts such as cuneiform and hieroglyphics. With their simple association between a character and a specific sound, Canaanite writing proved the basis from which modern Western alphabets evolved. [Source: Chris Klimek, Smithsonian magazine, March 2023]

In 2016, a team of researchers, led by professor Yosef Garfinkel from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, unearthed an ivory comb from an archaeological site at Tel Lachish, about 35 miles southwest of Jerusalem. that was later discovered to some of the world’s oldest alphabetic writing on it according to a study published in the Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology. The tiny comb is only about four centimeters (1.5 inches) wide and 2.5 centimeters (1 inch tall). The teeth on the top have broken off, but some remain on the bottom, photos show. When it was first found is was classified as a bone. Preserved remains of lice were found on the comb’s teeth, indicating its purpose, the study said. [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, November 9, 2022]

Analyzing the comb’s material revealed it was made of expensive elephant ivory, likely imported from Egypt, professor Rivka Rabinovich from the Hebrew University and professor Yuval Goren from Ben Gurion University said. On the comb’s rough surface, 17 tiny letters were engraved. They came from the earliest-known alphabet created by Canaanites around 1800 B.C.,

Rarity of Canaanite Alphabetic Writing

The discoveries made in Tel Lachish in 2020 including part of a Canaanite inscription on a piece of pottery. Live Science reported: That inscription shows the first known use of the letter "samekh," which also appears in the Hebrew alphabet as a version of the English "s" sound. The discovery is especially important because the ancient Canaanites are now thought to have invented the first alphabet. [Source: Tom Metcalfe. Live Science, February 24, 2020]

Canaanite inscriptions are very rare. Only a few have been found in the past 30 or 40 years, Garfinkel said. "We had A, and B, and C, and D … but there was one letter that was never found before — the Canaanite or Hebrew 'samekh'," he said. "In this temple, we found a fragment of an inscription, and on it appears the earliest known letter samekh in the world."

"Before this, you have the cuneiform writing technique in Mesopotamia, and you have the hieroglyph system in Egypt," Garfinkel said. "But these were very complicated writing techniques with hundreds of signs, and only scribes who learned for years knew how to read and write." In contrast, the Canaanite alphabet could be written and read much more easily. "The Canaanites invented the alphabet, and it spread all over the world — from Canaanite to Hebrew, then to Greek and Latin, and then to English," he said. "And it is now very common all over the world."

One of the World’s Oldest Written Sentences Blasts Canaanite Hair and Beard Lice

One of the oldest known sentences ever written — found on the comb described above — was a plea written in a Canaanite language ro wtach out for lice. Live Science reported: Archaeologists made the discovery several years after unearthing the hair comb in 2016 from Tel Lachish. The site was once a city inhabited by the Canaanites. [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, November 14, 2022]

One side contained six teeth, which were likely used for untangling hair, while the other had 14 finer teeth for removing lice and their eggs, the researchers said. It wasn't until 2021 that Madeleine Mumcuoglu, a researcher at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where the piece has been stored, noticed symbols chiseled into the comb. Using the zoom function on her smartphone, she was able to get a close enough image to decipher the cryptic message, which read, "May this tusk root out the lice of the hair and the beard."

Daniel Vainstub, the epigrapher at Ben-Gurion University, told Live Science: "For the first time we have a complete sentence in a Canaanite dialect," he added. "We know dozens of Canaanite inscriptions, but all of them hold two or three words. Now we have a complete and clear sentence that allows us to see the language, the grammar, the syntax, etc. and compare it with other Semitic languages like Biblical Hebrew."

Archaeologists were unsuccessful in radiocarbon-dating the comb, but they were able to narrow down its age, since "the [Canaanite] alphabet was invented in the 19th century B.C., and this inscription most probably should be dated to the 17th century B.C.," Vainstub said.

There's no indication of the comb's owner, but researchers think it may have belonged to a wealthy individual, considering that it came from an elephant tusk. Canaan didn't have any elephants during that time period, so the material likely came from Egypt, according to a statement. "Ivory was a very expensive and exclusive material," Vainstub said. "Undoubtedly the comb belonged to a wealthy man." The translated version of the study was published October 12, 2022 in the journal Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology.

3,500-Year-Old Alphabet Missing Link Found at Tek Lachish, Israel

In 2021, a research team led by Felix Höflmayer, an archaeologist at the Austrian Archaeological Institute, published an article in Antiquity describing the discovery of a 3,500-year-old milk jar fragment unearthed at Tel Lachish in Israel with a partial inscription that Höflmayer said was “currently the oldest securely dated alphabetic inscription from the Southern Levant.” [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, April 25, 2021]

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Höflmayer and his team suggests that the inscription doesn’t just provide another data point, its early date changes how we think about the emergence of the alphabet. Up until 1550 BCE the Hyskos, a group from the Levant, ruled parts of northern Egypt as well as controlling much of the Levant. The fact that hieroglyphic symbols are also found on the jar might suggest that whomever produced the inscription was familiar with both hieroglyphic and emergent alphabetic script. “The proliferation [of the alphabet] into the Southern Levant,” the authors write, “probably happened during the (late) Middle Bronze Age and the Egyptian Second Intermediate Period, when a Dynasty of Western Asiatic origin (the Hyksos) ruled the northern parts of Egypt.” What this means is “that early alphabetic writing in the Southern Levant developed independently of, and well before, the Egyptian domination and floruit of hieratic writing during the … thirteenth and twelfth centuries BC.”

The inscription itself is fragmentary and is thus near impossible to decipher. The first word contains the letters ayin, bet and dalet while the second begins with the letters nun, pe, and tav. Anyone who has learned Hebrew will recognize the names of these letters as part of the Semitic alphabet. Though the early version used in the Arabian Peninsula are visually quite different from the Hebrew alphabet used today, there’s a clear connection between the two.

What’s particularly interesting, given the way in which many scholars have tied the development of alphabetic script to the history of oppression, is that the letters of the first word (ayin, bet, dalet) spell the word “slave.” Though Höflmayer stresses that this could be purely accidental as these letters form the beginning of many ancient words, some might wish to read more here. Perhaps it is possible that an enslaved person was involved in the production of this inscription we certainly shouldn’t exclude this possibility form the history of writing.

Lost Canaanite Language Deciphered with 'Rosetta Stone'-like Tablets

In January 2023, scientists announced they had deciphered a cryptic lost Canaanite language using two ancient clay 'Rosetta Stone'-like tablets from Iraq. The tablets were found in Iraq in the early 1990s, with scholars studying them beginning in 2016 and and discovering they contained details in Akkadian of the "lost" Amorite language. Live Science reported: The two ancient clay tablets are covered from top to bottom in cuneiform writing contain that has remarkable similarities with ancient Hebrew. The tablets, thought to be nearly 4,000 years old, record phrases in the almost unknown language of the Amorite people, who were originally from Canaan. but who later founded a kingdom in Mesopotamia. These phrases are placed alongside translations in the Akkadian language, which can be read by modern scholars. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, January 31, 2023

In effect, the tablets are similar to the famous Rosetta Stone, which had an inscription in one known language (ancient Greek) in parallel with two unknown written ancient Egyptian scripts (hieroglyphics and demotic.) In this case, the known Akkadian phrases are helping researchers read written Amorite. "Our knowledge of Amorite was so pitiful that some experts doubted whether there was such a language at all," researchers Manfred Krebernik and Andrew R. George told Live Science. But "the tablets settle that question by showing the language to be coherently and predictably articulated, and fully distinct from Akkadian."

See Amorite Language Deciphered with 'Rosetta Stone'-like Tablets Under MARI AND THE BIBLICAL AMORITES africame.factsanddetails.com

Cylinder Seals in Canaanite Palestine

Abercrombie wrote: “Cylinder seals continue to be used by Bronze Age society despite the increase in the number of scarabs. In this part of the Levant, a new style of Glyptic Art, which we designate as Syrian, develops. Some the characteristic features are the mixture of Mesopotamian and Egyptian motifs, animal motifs (e.g. combat scenes), and depictions of human-like figures we interpret as deities. [Sources: John R. Abercrombie, University of Pennsylvania, James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), Princeton, Boston University, bu.edu/anep/MB.html |*|]

Iron Age seals

“Cylinder seals in Syrian style continue to be found in Late Bronze (1570 - 1200 B.C.) levels, though many archaeologists feel that they may be heirlooms from the Middle Bronze II. A new type of cylinder seal, of which there are hundreds of examples, is called Mitanni style. This seal has friezes of animals and men or gods. A common motif, the sacred tree surrounded usually by antelopes or goats, occurs on these seals as well as other artifacts (e.g. pottery). The tree motif varies greatly in detail from just simple rendering of a tree or just a branch to a complete scene of tree, processional characters, animals and mythic griffins. Towards the end of the Bronze Age, designs on cylinder seals become more and more influenced by the nature of other signet items like the scarab. These later cylinder seals become more like a stamp plaque and are divided into panels with short phrases in hieroglyphic or designs in one panel and animal (s) or figure (s) in the other. Towards the end of the Bronze Age, stamp seals and plaques begin to appear. Such plaques and seals might be consider degenerative forms of cylinder seals and scarabs respectively. Seals, in particular, will become a more preferred signet item in the Iron Age.” |*|

Two motifs dominate seals of the Iron Age (1200 - 550 B.C.). The sacred tree with animal (s) and sometimes an individual continues the motif characteristic of many Late Bronze Age (1570 - 1200 B.C.) seals. A second motif, of a seated individual before a table and being served by an animal or human, parallels other depictions on the ivories from Megiddo and the Ahiram sarcophagus. Stamp seals first appear at the end of the Late Bronze Age (1570 - 1200 B.C.) and continue to be produce in Iron I. Some of these seals are designated scaraboids, thus, indicating perhaps their derivation from Egyptian scarabs. The iconography on these early seals include animals, plants and adult males. Few — if any — of these seals are inscribed. |*|

“The Late Iron Age seals continue into The Late Iron Age. A new inscribed seal, however, is the more common form of this period. Such round seals consist of two inscribed lines, the first giving the owner's name ("belonging to X"), and the second usually the person's title. Some of these inscribed seals, probably those belonging to important officials, may have an animal (e.g. lion or rooster). A few of the seals can, in fact, be identified with individuals known from biblical sources (ANEP, 277). |*|

“Seals and other inscriptional material, including dockets from Samaria or inscribed jar handles from Gibeon, are valuable particularly in discussion of the religiosity of the northern and southern kingdoms. Most of the inscribed names contain a theophoric element, baal or yahu, for instance. If we have a sufficient representation of such seals we perhaps can hypothesize the cultic allegiance of a particular site or group based upon the chosen theophoric elements. By the way, this same procedure can be applied to the biblical text as well and does provide for some fascinating observations about the rise in the cult of yahu and the decline in that of baal. |*|

Inscriptions in the Iron Age

Abercrombie wrote: “The Mesha Stone, discovered at Dhiban, is the longest known inscription from the region. This commemorative stela of King Mesha of Moabite covers the king's conquests of the lands north of Dhiban around 850 B.C.. “The Siloam tomb inscription generally is dated to the seventh century and describes the manner in which the Siloam water tunnel was cut by two different gangs of workmen. [Sources: John R. Abercrombie, University of Pennsylvania, Department of Religious Studies, University of Pennsylvania; James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), Princeton, Boston University, bu.edu/anep/MB.html |*|]

Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions

“Royal stamp seals date to the eighth and/or seventh centuries. The inscribed seals occur on storage jar handles and contain the phrase (lmlk = "to/for the king") and the name of one of four cities (Hebron, Sochoh, Ziph or mmsht). The seals are of three types: winged sun-disk, a four-winged scarab (naturalistic style) and a four-winged scarab (schematic style). Until recently most archaeologists dated the inscribed seals to the reigns of seventh century monarchs, particularly Josiah. However, seals have been found in situ at Lachish III that recently has been redated to the late eighth century. The Lachish ostraca date to the last days of the Judaean kingdom, beginning sixth century, and are military dispatches the record the methodical demise of garrison in the hill country. |*|

“To date, the largest collection of Late Bronze inscriptional material uncovered in Palestine was unearthed at Beth Shan. Two almost complete stelae, one of Ramesis II and the other of Seti I, describe campaigns in the regions east of Beth Shan. Other fragmentary stelae were also found. Votive stelae dedicated to gods by their worshippers form the next largest group of inscriptions. Some of these texts do date to Iron I, yet are included here since culturally they seem to reflect to Bronze rather than Iron Age. A third group of inscriptions, inscribed door lintels, were uncovered in Strata VI, now dated to very beginning of Iron I. |*|

The 21 ostraca from Lachish — often referred to as the Letters of Lachish — belong to the period of the Neo-Babylonian siege (598/588 B.C.) of the Lachish, near Mount Hebron in present-day Israel. One of them reads: “May Yahweh cause my lord to hear this very day tidings of good! .... And let (my lord) know that we are watching for the signals of Lachish, according to all that indications which my lord hath given, for we cannot see Azekah. [Source: James B. Pritchard, “Ancient Near Eastern Texts,” (ANET) pp. 321-322, Princeton, 1969, web.archive.org]

Mesha Stela (9th Century B.C.)

The Mesha Stela (9th Century B.C.), the longest inscription from Palestine, records the victories of King Mesha of Moab (2 Kings 3:4) over the tribal inheritance of Reuben. It reads: “I (am) Mesha, son of Chemosh-[ . . . ], king of the DiboniteÑmy father (had) reigned over Moab thirty years, and I reigned after my father,Ñ (who) made this high place for Chemosh in Qarhoh [ . . .] because he saved me from all the kings and caused to triumph over all my adversaries. As for Omri, king of Israel, he humbled Moab many years lit. days), for Chemosh was angry at his land. And his son followed him and he also said, "I will humble Moab." In my time he spoke (thus), but I have triumphed over him and over his house, while Israel hath perished for ever ! (Now) Omri had occupied the land Medeba, and (Israel) had dwelt there in his time, and half the time of his son (Ahab), forty years; I Chemosh dwelt there in my time. And I built Baal-meon, making a reservoir in it, and I built (10) Qaryaten. [Source: James B. Pritchard, “Ancient Near Eastern Texts,” (ANET), Princeton, 1969, pp. 320-321, web.archive.org]

“Now the men of Gad had ways dwelt in the land of Ataroth, and the king Israel had built Ataroth for them; but I fought against the town and took it and slew all the people of the town as satiation (intoxication) for Chemosh Moab. And I brought back from there Arel (or Oriel), its chieftain, dragging him before Chemosh in Kerioth and I settled there men of Sharon and men of Maharith. And Chemosh said to me, "Go, take Nebo from Israel!" (15) So I went by night and fought against it from the break of dawn until noon, taking and slaying all, seven thousand men, boys, women, girls and maid-servants, for I had devoted them to destruction for (the god) Ashtar-Chemosh. And I took from there the [ . . . ] of Yahweh, dragging them before Chemosh. And the king of Israel had built Jahaz, and he dwelt there while he was fighting against me, but Chemosh drove him out before me. And (20) I took from Moab two hundred men, all first class (warriors), anili them against Jahaz and took it in order to attach it (the district of) Dibon.

Mesha Stone

“It was I (who) built Qarhoh, the wall of thc forests and the wall of the citadel; I also built its gates and I built its towers and I built the king's house, and I made both of its reservoirs for water inside the tower. And there was no cistern inside the town at Qarhoh, so I said to all the people, "Let each of you made a cistern for himself in his house!" And I cut beams for Qarhoh with Israelite captives. I built Aroer, and I made the highway in the Arnon (valley); I built Beth-bamoth, for it had been destroyed; I built Bezer — for it lay in ruines — with fifty men of Dibon, for all Dibon is (my) loyal dependency. And I reigned [in peace] over the hundred towns which I had added to the land. And I built (30) [. . .] Medeba and Beth-diblathen and Beth-baal-meon, and I set there the [. . .] of the land. And as for Hauronen, there dwelt in it [. . . And] Chemosh said to me, "Go down, fight against Hauronen. And I went down [ and I fought against the town and took it], and Chemosh dwelt there in my time.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons, Schnorr von Carolsfeld Bible in Bildern, 1860

Text Sources: John R. Abercrombie, University of Pennsylvania, Department of Religious Studies, University of Pennsylvania; James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), Princeton, Boston University, bu.edu/anep/MB.html; “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024