Home | Category: Babylonians and Their Contemporaries / Canaanites and Early Biblical Peoples / Canaanites and Early Biblical Peoples

AMORITES

Ebish II from Mari

The Amorites were an ancient Semitic-speaking people that dominated the history of Mesopotamia, Syria, and Palestine from about 2000 to about 1600 B.C. In the oldest cuneiform sources (c. 2400–c. 2000 B.C.), the Amorites were equated with the West, though their true place of origin was most likely Arabia, not Syria. They were troublesome nomads and were believed to be one of the causes of the downfall of the 3rd dynasty of Ur (c. 2112–c. 2004 bc). [Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica]

According to Encyclopaedia Britannica: “During the 2nd millennium B.C., the Akkadian term Amurru referred not only to an ethnic group but also to a language and to a geographic and political unit in Syria and Palestine. At the beginning of the millennium, a large-scale migration of great tribal federations from Arabia resulted in the occupation of Babylonia proper, the mid-Euphrates region, and Syria-Palestine. They set up a mosaic of small kingdoms and rapidly assimilated the Sumero-Akkadian culture. It is possible that this group was connected with the Amorites mentioned in earlier sources; some scholars, however, prefer to call this second group Eastern Canaanites, or Canaanites.

“Almost all of the local kings in Babylonia (such as Hammurabi of Babylon) belonged to this stock. One capital was at Mari (modern Tall al- arīrī, Syria). Farther west, the political centre was alab (Aleppo); in that area, as well as in Palestine, the newcomers were thoroughly mixed with the Hurrians. The region then called Amurru was northern Palestine, with its centre at Hazor, and the neighbouring Syrian desert. In the dark age between about 1600 and about 1100 bc, the language of the Amorites disappeared from Babylonia and the mid-Euphrates; in Syria and Palestine, however, it became dominant. In Assyrian inscriptions from about 1100 bc, the term Amurru designated part of Syria and all of Phoenicia and Palestine but no longer referred to any specific kingdom, language, or population.”

Morris Jastrow said: “The Amorites have generally been regarded as Semites. Professor Clay, we have seen, would regard Amurru as, in fact, the home of a large branch of the Semites; yet the manner in which the Old Testament contrasts the Canaanites—the old population of Palestine dispossessed by the invading Hebrews— with the Amorites, raises the question whether this contrast does not rest on an ethnic distinction. The Amoritish type as depicted on Egyptian monuments also is distinct from that of the Semitic inhabitants of Palestine and Syria. It is quite within the range of possibility that the Amorites, too, represent another non-Semitic factor further complicating the web of the Sumero-Akkadian culture, though it must also be borne in mind that the Amorites, whatever their original ethnic type may have been, became commingled with Semites, and in later times are not to be distinguished from the Semitic population of Syria. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/ ; Bible and Biblical History: ; Biblical Archaeology Society biblicalarchaeology.org ; Bible History Online bible-history.com Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks ; Jewish History Websites: Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ;

See Separate Article:BIBLICAL AMORITES africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Amorites and the Bronze Age Near East by Aaron A. Burke (2023) Amazon.com;

“The World Around the Old Testament: The People and Places of the Ancient Near East”

by Bill T. Arnold and Brent A. Strawn (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Amorites: The History and Legacy of the Nomads Who Conquered Mesopotamia and Established the Babylonian Empire” by Charles River Editors (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Amorite Kingdoms: The History of the First Babylonian Dynasty and the Other Mesopotamian Kingdoms Established by the Amorites” by Charles River Editors (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Empire of the Amorites (Classic Reprint) by Albert T. Clay Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Amorites (Amurru) of Mesopotamia by Kemal Yildirim (2017) Amazon.com;

“Amorite - All The Bible Teaches About” by Jerome Goodwin (2011) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament”

by James B. Pritchard Amazon.com ;

“Where God Came Down” by Joel P. Kramer Amazon.com ;

“Unearthing the Bible: 101 Archaeological Discoveries That Bring the Bible to Life” Amazon.com ;

“Zondervan Handbook of Biblical Archaeology: A Book by Book Guide to Archaeological Discoveries Related to the Bible” by J. Randall Price and H. Wayne House Amazon.com ;

“A History of Babylon (2200 BC - AD 75" by Paul-Alain Beaulieu (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian Empire” by Enthralling History (2022) Amazon.com;

“The City of Babylon: A History, C. 2000 BC - AD 116" by Stephanie Dalley (2021) Amazon.com;

“The First Great Powers: Babylon and Assyria” by Arthur Cotterell (2019) Amazon.com;

“Civilizations of Ancient Iraq” by Benjamin R. Foster and Karen Polinger Foster ((2009) Amazon.com;

“A History of the Ancient Near East” by Marc Van De Mieroop (2003) Amazon.com;

“The Bible Unearthed” by I. Finkelstein and N. Asher Silberman Amazon.com ;

“Oxford Companion to the Bible” by Bruce M. Metzger and Michael David Coogan Amazon.com ;

“The Bible as History” by Werner Keller Amazon.com ;

“Historical Atlas of the Holy Lands” by K. Farrington Amazon.com ;

Amurru and the Origin of the Amorites

Mari pendant mask

The Amorites originated from Amurru. Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica:Amurru (or Amaru) was, in its earliest cuneiform attestations, simply a geographic name for the west, or for the deserts bordering the right bank of the Euphrates. This area, which stretched without apparent limit into the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, was traditionally the home of nomadic tribes of Semitic speech who were drawn to the civilized river valley as if by a magnet and invaded or infiltrated it whenever opportunity beckoned. In the process they became progressively acculturated — first as semi-nomads who spent part of the year as settled agriculturalists in an uneasy symbiosis with the urban society of the irrigation civilizations, and ultimately as fully integrated members of that society, retaining at most the linguistic traces of their origins. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

It was thus that, perhaps as early as about 2900 B.C., the first major wave of westerners had entered the Mesopotamian amalgam, and under the kings of Kish and Akkad became full partners in the Sumero-Akkadian civilization that resulted. When, however, the Akkadian sources themselves spoke of Amorites, as they did beginning with Shar-kali-sharri about 2150, they were alluding to a new wave of invaders from the desert, not yet acclimated to Mesopotamian ways. Such references multiply in the neo-Sumerian texts of the 21st century, and correlate with growing linguistic evidence based chiefly on the recorded personal names of persons identified as Amorites which shows that the new group spoke a variety of Semitic, ancestral to later Hebrew, Aramaic, and Phoenician.

Hebrew, Aramaic, and Phoenician languages (and some other dialects) are called West Semitic (or Northwest Semitic) by modern linguists, to distinguish them from the East Semitic, or Akkadian, language spoken in Mesopotamia. The latter, used side by side with the non-Semitic Sumerian, and often by one and the same speaker, was heavily influenced by Sumerian and developed along lines of its own; but it also reacted to the Amorite impact and split into two fairly distinct dialects: Babylonian in the south and Assyrian in the north.

Amorite Influences

Many cultural innovations of the second millennium, notably in religion and art, can be traced to the Amorites or at least people from Amarru and the Western Semitic regions.Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: Since the migrations moved in the direction of Syria-Palestine as well as of Mesopotamia, it is not surprising that numerous common traditions — linguistic, legal, and literary — crop up at both ends of the Asiatic Near East hereafter. Among these common traditions, those of the semi-nomadic wanderings preserved in the patriarchal narratives in Genesis, and elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible, deserve special notice. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

The glimpses they provide of tribal organization, onomastic practices, kinship patterns, rules of inheritance and land tenure, genealogical schemes, and other vestiges of nomadic life find analogies in cuneiform records. Yet they are preserved within the framework of a polished literary narrative too far removed from the times it presumes to describe to command uncritical confidence. Nonetheless, it is in this period, that it can be said, that the Levant (that is, the area of Syria-Palestine) begins at this time to emerge from prehistory into history.

The pattern established by the Amorites was to characterize Near Eastern history down to the present: it was only when the natural arenas of centralized political power in Mesopotamia and Egypt were in eclipse that the intervening area, destined by geography for division into petty states, enjoyed an opportunity to make its influence felt in unison.

Amorite Period (2000–1800 B.C.)

The beginning of the second millennium may be characterized as the era of the Amorites. The first Babylonian kings belonged to the Amorite Dynasty. Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: The simultaneous collapse of the Sargonic empire of Akkad and the Old Kingdom in Egypt provided such an opportunity, and already Shulgi of Ur had to construct a defensive wall, presumably at the point where the Tigris and Euphrates flow closest together, to deflect unwanted barbarians from the cities that lay to the south.

Shulgi was succeeded by two of his many sons, Amar-Sin and Shu-Sin, each of whom reigned for nine years. Like him, these conducted most of their military campaigns in the east, across the Tigris, but Shu-Sin greatly strengthened the wall, calling it "The one which keeps Didanum at bay" in a direct reference to the Amorite threat. He managed thereby to postpone the final reckoning, and even enjoyed divine honors in his lifetime beyond those of his predecessors. His son Ibbi-Sin, however, was less fortunate, and in native Mesopotamian traditions was remembered as the model of the ill-fated ruler. Unable to withstand the simultaneous onslaughts of Elamites and Subarians from the east and Amorites from the west, he appealed for help to Ishbi-Irra of Mari only to end up with Ishbi-Irra extorting ever more powers for himself until he was able to found a dynasty of his own at Isin, and subsequently allowing the capital city of Ur to be sacked and Ibbi-Sin to be carried off to exile and ultimate death and burial in Elam. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

The fall of Ur about 2000 B.C. did not mark so clear a break in the historical continuum as has sometimes been assumed. Ishbi-Irra paid homage to the Sumero-Akkadian traditions of the Ur III dynasty, reigning as king of Ur and perpetuating such time-honored practices as the cult of the deified king, the patronage of the priesthood and scribal schools of Nippur, and the installation of royal princes and princesses as priests and priestesses at the principal national shrines and of loyal officials as governors of the principal provinces. However, whether with his consent or not, these governors were now increasingly of Amorite stock, and wherever possible aspired to royal status for themselves and independence for their city. The latter course particularly characterized the situation beyond the immediate range of his control, notably at Ashur, Eshnunna, Dêr, and Susa beyond the Tigris, as well as upstream on the Euphrates and its tributaries. From Ashur and northern Mesopotamia, a lively trade soon carried Amorite and Akkadian influence even further afield, into Cappadocia.

Closer to home, the traditional central control was at first maintained, but even here the loyalty of the provinces was shortlived. For most of the 20th century, Ishbi-Irra's descendants at Isin were unchallenged as the successors of the kings of Ur, but before it was over, the Amorite governors of the southeast, probably based at the ancient city of Lagash, asserted their independence in order to protect the dwindling water resources of that region. Under Gungunum, they established a rival kingdom at Larsa which soon wrested Ur from Isin. In short succession, other Amorite chieftains established independent dynasties at Uruk, Babylon, Kish and nearly all the former provinces of the united kingdom, until Isin effectively controlled little more than its own city and Nippur. With the more distant marshes long since under Amorite rule, the 19th century was thus characterized by political fragmentation, with a concomitant outburst of warfare and diplomacy that embroiled all the separate petty states at one time or another.

The "staging area" for the Amorite expansion was probably the Jabel Bishri (Mt. Basar) which divides or, if one prefers, links the Euphrates River and the Syrian Desert. From here it was a comparatively short and easy march down the river to Babylonia or across the river to Assyria. The way to Egypt was not only longer but led through more hilly and intractable land. This may be one reason that the Amorite wave was somewhat longer in reaching the Egyptian border. When it did reach it, it confronted just such a wall as Shu-Sin (c. 2036–2028) had built "to keep Didanum at bay": in one of those curious parallels that punctuate Ancient Near Eastern history, they met the "Wall-of-the-Ruler, made to oppose the Asiatics and crush the Sand-Crossers," and attributed to the founder of the 12th Dynasty. But the extraordinary revitalization of the Egyptian monarchy by this dynasty (c. 1990–1780) was the real reason that the Amorite wave broke harmlessly at the Egyptian border and the characteristic petty statism that it brought in its train was deferred for two centuries.

Amorite Dynasty of the First Babylonian Empire

The first great dynasty for which ancient Babylon is known was West-Semitic and is likely the Amorite Dynasty referred to in the Old Testament. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia:“ The Babylonians called it the dynasty of Babylon, for, though foreign in origin, it may have had its actual home in that city, which it gratefully and proudly remembered. It lasted for 296 years and saw the greatest glory of the old empire and perhaps the Golden Age of the Semitic race in the ancient world. The names of its monarchs are: Sumu-abi (15 years), Sumu-la-ilu (35), Zabin (14), Apil-Sin (18), Sin-muballit (30); Hammurabi (35), Samsu-iluna (35), Abishua (25), Ammi-titana (25), Ammizaduga (22), Samsu-titana (31). [Source: J.P. Arendzen, transcribed by Rev. Richard Giroux, Catholic Encyclopedia |=|]

“Under the first five kings Babylon was still only the mightiest amongst several rival cities, but the sixth king, Hammurabi, who succeeded in beating down all opposition, obtained absolute rule of Northern and Southern Babylonia and drove out the Elamite invaders. Babylonia henceforward formed but one state and was welded into one empire. They were apparently stormy days before the final triumph of Hammurabi. The second ruler strengthened his capital with large fortifications; the third ruler was apparently in danger of a native pretender or foreign rival called Immeru; only the fourth ruler was definitely styled King; while Hammurabi himself in the beginning of his reign acknowledged the suzerainty of Elam.

“Whereas the Assyrian kings loved to fill the boastful records of their reigns with ghastly descriptions of battle and war, so that we possess the minutest details of their military campaigns, the genius of Babylon, on the contrary, was one of peace, and culture, and progress. The building of temples, the adorning of cities, the digging of canals, the making of roads, the framing of laws was their pride; their records breathe, or affect to breathe, all serene tranquility; warlike exploits are but mentioned by the way, hence we have, even in the case of the two greatest Babylonian conquerors, Hammurabi and Nabuchodonosor II, but scanty information of their deeds of arms.

"I dug the canal Hammurabi, the blessing of men, which bringeth the water of the overflow unto the land of Sumer and Akkad. Its banks on both sides I made arable land; much seed I scattered upon it. Lasting water I provided for the land of Sumer and Akkad. The land of Sumer and Akkad, its separated peoples I united, with blessings and abundance I endowed them, in peaceful dwellings I made them to live" -- such is the style of Hammurabi. In what seems an ode on the king, engraved on his statue we find the words: "Hammurabi, the strong warrior, the destroyer of his foes, he is the hurricane of battle, sweeping the land of his foes, he brings opposition to naught, he puts an end to insurrection, he breaks the warrior as an image of clay." But chronological details are still in confusion. In a very fragmentary list of dates the 31st year of his reign is given as that of the land Emutbalu, which is usually taken as that of his victory over western Elam, and considered by many as that of his conquest of Larsa and its king, Rim-Sin, or Eri-Aku. If the Biblical Amraphel be Hammurabi we have in Gen., xiv, the record of an expedition of his to the Westland previous to the 31st year of his reign. Of Hammurabi's immediate successors we know nothing except that they reigned in peaceful prosperity. That trade prospered, and temples were built, is all we can say. |=|

Mari

The ancient city of Mari, located in northern Syria on the middle Euphrates, south of its junction with the Habor (Khabur), was founded around 2900 B.C. and was thriving metropolis from around 2800 B.C. to its demise in 1760 B.C.. According to UNESCO: “Mari is an archaeological site of major significance. It was the royal city-state of the 3rd millennium B.C. Its discovery in 1933, followed by the discovery of Ebla in 1963, improved our understanding of Syria in the Bronze Age. Previously, we only had little information collected from Kings of Summer and Akkad inscriptions found in the current territory of Iraq.” The site has been on UNESCO’s tentative list since 1999. [Source: UNESCO]

Mari was among the first sites in Syria to be excavated. The city was part of an ancient Bronze-Age kingdom centered on modern Tell-Hariri, around 70 kilometers to the south of Der Ezzor. Syria. Impressive architectural remains have been excavated on the site, including palaces and temples from the Early Bronze Age when the city was an important center for metalworking. There is also evidence linking Mari and Ebla as far back as the 3rd millennium BC. [Source: University of Copenhagen ~~]

According to the University of Copenhagen: “The best documented period at the site is the Bronze Age, in particular royal palaces and temples dated to the Early Bronze Age, as well as an impressive Middle Bronze Age royal palace-the Zimri-Lim palace named after the last king of Mari before its destruction by Babylonian troops around 1760 BC. The range of artefacts found at the site include a rich and varied cuneiform tablet archive dating from 2000-1600 BC, which provides one of the most extensive archive collections of the period. Another palace has also been excavated and named the Šakkanakku royal palace, after a local governor during Akkadian domination of the city. Temples dedicated to local Syrian deities such as Ishtar as well as Mesopotamian gods such as Shamash have also been found at the site.” ~~

Amorite period pottery

According to Columbia Encyclopedia: “The site was discovered by chance in the early 1930s by Arabs digging graves and has subsequently been excavated by the French. The earliest evidence of habitation goes back to the Jemdet Nasr period in the 3d millennium BC, and Mari remained prosperous throughout the early dynastic period. The temple of Ishtar and other works of art show that Mari was at this time an artistic center with a highly developed style of its own. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia]

“As the commercial and political focus of W Asia c.1800 BC, its power extended over 300 mi a1 (480 km) from the frontier of Babylon proper, up the Euphrates, to the border of Syria. The archives of the great King Zimri-lim, a contemporary of Hammurabi in the 18th cent. BC, were discovered in 1937. They contain over 20,000 clay documents, which have made it possible to fix the dates of events in Mesopotamia in the 2d millennium BC Also found at Mari is the great palace complex of Zimri-lim consisting of more than 200 rooms and covering 5 acres (2 hectares).” Mari was conquered by Hammurabi around 1700 B.C. and Babylon then became the center of W Asia. Mari never regained its former status. Between 1760 and 1757 BC, Mari was destroyed by Hammurabi of Babylon.

Mari, the World’s First Planned City?

According to ancient-origins.net Although only a third of the city has survived (the rest having been washed away by the Euphrates), excavations at Mari have provided us with some information about this ancient site. For instance, archaeologists have discovered that Mari was designed and built as two concentric rings. The outer ring was meant to protect the city from the flooding caused by the Euphrates, whilst the inner ring served as a defense against human enemies. Astonishing architectural discoveries for the age of the site include several palaces and temples in various layers. [Source: ancient-origins.net ]

“Mari occupied a geographically strategic position in the landscape, between Babylonia in southern Mesopotamia and the Taurus Mountains, which was rich in natural resources, to the north, in modern day Turkey. As a result of this, Mari flourished as an important city state. It is thought to have been inhabited by people who migrated from the kingdoms of Ebla and Akkad. As the city is located between the southern Mesopotamian city states and the Taurus Mountains, as well as the northern part of Syria, Mari was able to control the flow of trade. For example, timber and stone from northern Syria had to pass through Mari to reach the south. In addition, metal ores came from the Taurus Mountains, and some of the city’s inhabitants began to specialize in copper and bronze smelting, thus increasing Mari’s significance.

“It is believed that the city had been entirely planned prior to its construction, hence, it is often regarded as an example of complex urban planning, and the first known of its kind in the world. As Mari is located on the Euphrates, and relied on trade, it also developed a system of canals, another piece of evidence for urban planning. A linkage canal, for example, allowed boats travelling along the river to gain access to the city, as well as provided water for its inhabitants. Additionally, there was also an irrigation canal for agricultural purposes, and a navigational canal that flowed past the city on the opposite side of the river. This canal provided boats with an alternate route into the city – a straight passage as opposed to the winding Euphrates. The entry points were controlled by the city, and Mari profited from the tolls collected there.”

Mari

Mari Under Zimri-Lim

Mary Shepperson wrote in The Guardian: “Ruling Mari wasn’t an easy job; the city was surrounded by more powerful kingdoms and beset by frequent internal troubles. King Yaggid-Lim was killed by his servants, while Yahdun-Lim was assassinated by his own son, who in turn was also assassinated after a reign of just two years. The best-known king of Mari was Zimri-Lim; a contemporary of the mighty Hammurabi of Babylon, famous for the earliest surviving law code. [Source: Mary Shepperson, The Guardian, April 19, 2018 ++]

“Zimri-Lim, whose father also seems to have been assassinated by untrustworthy servants, managed to wrestle Mari back from a rival royal house. He married Shibtu, a princess from the kingdom of Yamad, centred at modern Aleppo. They had at least eight daughters and many letters between the king and his grown-up daughters survive to illustrate a close and fond fatherly relationship. ++

“Zimri-Lim was less successful in his relationship with Hammurabi. After being an ally of Babylon in its wars with Elam and the city state of Larsa, the diplomatic relationship between Zimri-Lim and Hammurabi gradually soured, culminating in a Babylonian army being dispatched to conquer Mari in 1761 BC. It’s impossible to tell how much more of this history may have been hacked out of the ground by the IS-sponsored looters, written on tablets which were sold to fund the fighting. Zimri-Lim disappeared from the historical record when his city fell, presumably because he didn’t survive the encounter, but his palace did survive along with the records of his fourteen-year reign.” ++

Mari Palace

Mary Shepperson wrote in The Guardian: “Mari was home to an extraordinary palace. The earliest major structure dates to around 2500-2300 BC, and part of this early palace was restored and preserved at the site, providing a unique opportunity to walk through a third millennium BC Mesopotamian palace, standing almost to its roof beams. [Source: Mary Shepperson, The Guardian, April 19, 2018 ++]

“For archaeologists and historians, Mari’s royal palace is more famous in its later form. In around 1800 BC the palace was remodelled and expanded by the Lim dynasty and the excavation of this building has provided the most complete picture available of the life of a royal palace and the functioning of a Bronze Age city state. This is in part due to the good preservation of the architecture and the almost complete excavation of the palace’s 300 rooms, but also to the 25,000 cuneiform tablets recovered during the excavations, which mostly date to this time. The texts preserved on the tablets have left us the names of the rulers of Mari, provided a wealth of detail about the city and its people, and opened an exceptional window on the politics and diplomacy of the ancient Near East through the preservation of royal letters between the kings of Mari and the rulers of neighbouring kingdoms. ++

“The palace constructed by the kings of Mari was of unusual magnificence, and the diplomatic texts suggest it was famous in its day as one of the largest and most luxurious royal palaces in existence, the envy of other rulers. The huge courtyards were planted with palm trees and the walls of the palace were painted with elaborate scenes and decorative designs, including a large fresco showing the investiture of Zimri-Lim as King, now displayed in the Louvre. The palace’s chapel contained a life-sized statue of a goddess, which was drilled through so that real water could run from the mouth of the vase held in the goddess’ hands.”++

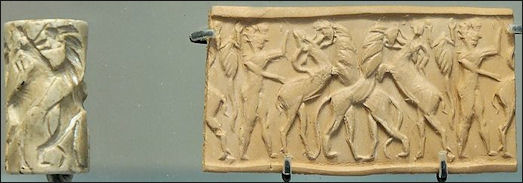

Mari cylinder seal of a battle

Mari and the Amorites

The inhabitants of Mari were referred to as Amorites in the Old Testament and spoke a language related to Hebrew. According to biblearchaeology.org, “From about 2000 to 1760 B.C., “Mari was the capital of the Amorites. Amorites were spread far and wide throughout the ancient Near East, including the hill country of Canaan vanquished by the Israelites (Nm 13:29; Jos 10:6).” The enormous palace covers six acres, with nearly 300 rooms on the ground level and an equal number on a second floor. “It was in use from ca. 2300 BC until its destruction by Hammurabi in 1760 BC. An archive of about 15,000 texts from the final years of the palace provides a detailed insight into the common social, economic and legal practices of that time. Contained in the archive are administrative and legal documents, letters, treaties, and literary and religious texts. [Source: biblearchaeology.org **

“The value of the Mari texts for Biblical studies lies in the fact that Mari is located in the vicinity of the homeland of the Patriarchs, being about 200 mi (320 km) southeast of Haran. It thus shares a common culture with the area where the Patriarchs originated. Some documents detail practices such as adoption and inheritance similar to those found in the Genesis accounts. The tablets speak of the slaughtering of animals when covenants were made, judges similar to the judges of the Old Testament, gods that are also named in the Hebrew Bible, and personal names such as Noah, Abram, Laban and Jacob. A city named Nahur is mentioned, possibly named after Abraham’s grandfather Nahor (Gn 11:22-25), as well as the city of Haran where Abraham lived for a time (Gn 11:31-12:4). Hazor is spoken of often in the Mari texts and there is a reference to Laish (Dan) as well. A unique collection of 30 texts deals with prophetic messages that were delivered to local rulers who relayed them to the king.” **

Decline of Ur, the Amorites and Gutians

Of the kings after Shar-kali-sharri (c. 2217-c. 2193 B.C.), only the names and a few brief inscriptions have survived. Quarrels arose over the succession, and the dynasty went under, although modern scholars know as little about the individual stages of this decline as about the rise of Akkad. [Source: piney.com]

Two factors contributed to its downfall: the invasion of the nomadic Amurrus (Amorites), called Martu by the Sumerians, from the northwest, and the infiltration of the Gutians, who came, apparently, from the region between the Tigris and the Zagros Mountains to the east. This argument, however, may be a vicious circle, as these invasions were provoked and facilitated by the very weakness of Akkad. In Ur III the Amorites, in part already sedentary, formed one ethnic component along with Sumerians and Akkadians. The Gutians, on the other hand, played only a temporary role, even if the memory of a Gutian dynasty persisted until the end of the 17th century B.C.. As a matter of fact, the wholly negative opinion that even some modern historians have of the Gutians is based solely on a few stereotyped statements by the Sumerians and Akkadians, especially on the victory inscription of Utu-hegal of Uruk (c. 2116-c. 2110). While Old Babylonian sources give the region between the Tigris and the Zagros Mountains as the home of the Gutians, these people probably also lived on the middle Euphrates during the 3rd millennium.

According to the Sumerian king list, the Gutians held the "kingship" in southern Mesopotamia for about 100 years. It has long been recognized that there is no question of a whole century of undivided Gutian rule and that some 50 years of this rule coincided with the final half century of Akkad. From this period there has also been preserved a record of a "Gutian interpreter." As it is altogether doubtful whether the Gutians had made any city of southern Mesopotamia their "capital" instead of controlling Babylonia more or less informally from outside, scholars cautiously refer to "viceroys" of this people. The Gutians have left no material records, and the original inscriptions about them are so scanty that no binding statements about them are possible.

Mari, the land of Amorites

Amorites, Akkadians and Hittites

Morris Jastrow said: “From the days of Sargon we find frequent traces of the Amorites; and there is at least one deity in the pantheon of this early period who was imported into the Euphrates Valley from the west, the home of the Amorites. This deity was a storm god known as Adad, appearing in Syria and Palestine as Hadad. According to Professor Clay, most of the other prominent members of what eventually became the definitely constituted Babylonian pantheon betray traces of having been subjected to this western influence. Indeed, Professor Clay goes even further and would ascribe many of the parallels between Biblical and Babylonian myths, traditions, customs, and rites to an early influence exerted by Amurru (which he regards as the home of the northern Semites) on Babylonia, and not, as has been hitherto assumed, to a western extension of Babylonian culture and religion. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“It is too early to pronounce a definite opinion on this interesting and novel thesis; but, granting that Professor Clay has pressed his views beyond legitimate bounds, there can no longer be any doubt that in accounting for the later and for some of the earlier aspects of the Sumero-Akkadian civilisation this factor of Amurru must be taken into account; nor is it at all unlikely that long before the days of Sargon, a wave of migration from the north and north-west to the south and south-east had set in, which brought large bodies of Amorites into the Euphrates Valley as well as into Assyria. The circumstance that, as has been pointed out, the earliest permanent settlements of Semites in the Euphrates Valley appear to be in the northern portion, creates a strong presumption in favour of the view which makes the Semites come into Babylonia from the north-west.

“Hittites do not make their appearance in the Euphrates Valley until some centuries after Sargon, but since it now appears that ca. 1800 B.C. they had become strong enough to invade the district, and that a Hittite ruler actually occupied the throne of Babylonia for a short period, we are justified in carrying the beginnings of Hittite influence back to the time at least of the Ur dynasty. This conclusion is strengthened by the evidence for an early establishment of a Hittite principality in north-western Mesopotamia, known as Mitanni, which extended its sway as early at least as 2100 B.C. to Assyria proper.

“Thanks to the excavations conducted by the German expedition at Kalah-Shergat (the site of the old capital of Assyria known as Ashur), we can now trace the beginnings of Assyria several centuries further back than was possible only a few years ago. The proper names at this earliest period of Assyrian history show a marked Hittite or Mitanni influence in the district, and it is significant that Ushpia, the founder of the most famous and oldest sanctuary in Ashur, bears a Hittite name. The conclusion appears justified that Assyria began her rule as an extension of Hittite control. With a branch of the Hittites firmly established in Assyria as early as ca. 2100 B.C., we can now account for an invasion of Babylonia a few centuries later. The Hittites brought their gods with them, as did the Amorites, and, with the gods, religious conceptions peculiarly their own. Traces of Hittite influence are to be seen e.g., in the designs on the seal cylinders, as has been recently shown by Dr. Ward, who, indeed, is inclined to assign to this influence a share in the religious art, and, therefore, also in the general culture and religion, much larger than could have been suspected a decade ago.

“Who those Hittites were we do not as yet know. Probably they represent a motley group of various peoples, and they may turn out to be Aryans. It is quite certain that they originated in a mountainous district, and that they were not Semites. We should thus have a factor entering into the Babylo-nian-Assyrian civilisation—leaving its decided traces in the religion—which was wholly different from the two chief elements in that civilisation—the Sumerian and the Akkadian."

Amorite Language Deciphered with 'Rosetta Stone'-like Tablets

Sargon of Akkad

In January 2023, scientists announced they had deciphered a cryptic lost Canaanite language using two ancient clay 'Rosetta Stone'-like tablets from Iraq. The tablets were found in Iraq in the early 1990s, with scholars studying them beginning in 2016 and and discovering they contained details in Akkadian of the "lost" Amorite language. Live Science reported: The two ancient clay tablets are covered from top to bottom in cuneiform writing contain that has remarkable similarities with ancient Hebrew. The tablets, thought to be nearly 4,000 years old, record phrases in the almost unknown language of the Amorite people, who were originally from Canaan. but who later founded a kingdom in Mesopotamia. These phrases are placed alongside translations in the Akkadian language, which can be read by modern scholars. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, January 31, 2023

In effect, the tablets are similar to the famous Rosetta Stone, which had an inscription in one known language (ancient Greek) in parallel with two unknown written ancient Egyptian scripts (hieroglyphics and demotic.) In this case, the known Akkadian phrases are helping researchers read written Amorite. "Our knowledge of Amorite was so pitiful that some experts doubted whether there was such a language at all," researchers Manfred Krebernik and Andrew R. George told Live Science in an email. But "the tablets settle that question by showing the language to be coherently and predictably articulated, and fully distinct from Akkadian."

Krebernik, a professor and chair of ancient Near Eastern studies at the University of Jena in Germany, and George, an emeritus professor of Babylonian literature at the University of London's School of Oriental and African Studies, published their research describing the tablets in the latest issue of the French journal Revue d'assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale (Journal of Assyriology and Oriental Archaeology). The two Amorite-Akkadian tablets were discovered in Iraq about 30 years ago, possibly during the Iran-Iraq War, from 1980 to 1988; eventually they were included in a collection in the United States. But nothing else is known about them, and it's not known if they were taken legally from Iraq.

'Rosetta Stone'-like Tablet Determined to a Kind of Amorite Guidebook

According to to Live Science: Krebernik and George started studying the tablets in 2016 after other scholars pointed them out. By analyzing the grammar and vocabulary of the mystery language, they determined that it belonged to the West Semitic family of languages, which also includes Hebrew (now spoken in Israel) and Aramaic, which was once widespread throughout the region but is now spoken only in a few scattered communities in the Middle East. After seeing the similarities between the mystery language and what little is known of Amorite, Krebernik and George determined that they were the same, and that the tablets were describing Amorite phrases in the Old Baylonian dialect of Akkadian.

The account of the Amorite language given in the tablets is surprisingly comprehensive. "The two tablets increase our knowledge of Amorite substantially, since they contain not only new words but also complete sentences, and so exhibit much new vocabulary and grammar," the researchers said. The writing on the tablets may have been done by an Akkadian-speaking Babylonian scribe or scribal apprentice, as an "impromptu exercise born of intellectual curiosity," the authors added. Yoram Cohen, a professor of Assyriology at Tel Aviv University in Israel who wasn't involved in the research, told Live Science that the tablets seem to be a sort of "tourist guidebook" for ancient Akkadian speakers who needed to learn Amorite. One notable passage is a list of Amorite gods that compares them with corresponding Mesopotamian gods, and another passage details welcoming phrases. "There are phrases about setting up a common meal, about doing a sacrifice, about blessing a king," Cohen said. "There is even what may be a love song. … It really encompasses the entire sphere of life."

Many of the Amorite phrases given in the tablets are similar to phrases in Hebrew, such as "pour us wine" — "ia -a -a -nam si -qí-ni -a -ti" in Amorite and "hasqenu yain" in Hebrew — although the earliest-known Hebrew writing is from about 1,000 years later, Cohen said. "It stretches the time when these [West Semitic] languages are documented. … Linguists can now examine what changes these languages have undergone through the centuries," he said.

Akkadian was originally the language of the early Mesopotamian city of Akkad (also known as Agade) from the third millennium B.C., but it became widespread throughout the region in later centuries and cultures, including the Babylonian civilization from about the 19th to the sixth centuries B.C. Many of the clay tablets covered in the ancient cuneiform script were written in Akkadian, and a thorough understanding of the language was a key part of education in Mesopotamia for more than a thousand years.

Biblical Amorites

Poussin's "Joshua's Victory Over the Amorites"

The Amorites are a people mentioned repeatedly in the Old Testament, along with the Canaanites and Hittites. The term Amorites is used in the Bible to refer to certain highland mountaineers who inhabited the land of Canaan, described in Genesis 10:16 as descendants of Canaan, the son of Ham. They are described as a powerful people of great stature "like the height of the cedars" (Amos 2:9) who had occupied the land east and west of the Jordan. The height and strength mentioned in Amos 2:9 has led some Christian scholars, including Orville J. Nave, who wrote the classic Nave's Topical Bible, to refer to the Amorites as "giants". [Source: Wikipedia +]

The Amorite king, Og, was described as the last "of the remnant of the Rephaim" (Deuteronomy 3:11). The terms Amorite and Canaanite seem to be used more or less interchangeably, Canaan being more general and Amorite a specific component among the Canaanites who inhabited the land. +

The Biblical Amorites seem to have originally occupied the region stretching from the heights west of the Dead Sea (Gen. 14:7) to Hebron (13:8; Deut. 3:8; 4:46–48), embracing "all Gilead and all Bashan" (Deut. 3:10), with the Jordan valley on the east of the river (4:49), the land of the "two kings of the Amorites". Sihon and Og (Deut. 31:4; Joshua 2:10; 9:10). Both Sihon and Og were independent kings. The Amorites seem to have been linked to the Jerusalem region, and the Jebusites may have been a subgroup of them (Ezek. 16:3). The southern slopes of the mountains of Judea are called the "mount of the Amorites" (Deut. 1:7, 19, 20). +

See Separate Article:BIBLICAL AMORITES africame.factsanddetails.com

Destruction of Mari by Islamic State

Mari was one of the first archaeological sites to be occupied by Islamic State and suffered from destruction and looting while under its control.Mary Shepperson wrote in The Guardian: “When Islamic State emerged, the part of Deir ez-Zor province in which Mari lies was one of the first areas to fall under its control in early 2014. Under IS, the site suffered an immediate explosion of looting; satellite images revealed the change from archaeological site to lunar landscape in a matter of months. More than 1,500 new looting pits were recorded at Mari between 2013 and 2015, likely representing the removal of a huge quantity of ancient objects, sold into the illegal antiquities market to fund Isis and its war. [Source: Mary Shepperson, The Guardian, April 19, 2018]

“Sadly, this is a story common to many archaeological sites across the region, but Mari isn’t just another site. For archaeologists it’s one of the most important sites so far excavated for those interested in understanding the great urban centres of Bronze Age Mesopotamia, or in diving into the turbulent politics of the second millennium BC.

“This palace area is now very badly damaged. Its protective roof was compromised by a sand storm in 2011, and the security situation at that time left it impossible to make repairs, but the recently released photos show that large parts of the palace’s 2m thick walls have now collapsed. Prof Pascal Butterlin, who directed excavations at the site up until 2010, believes such a level of destruction suggests that explosives, either ground based or more likely from air strikes, were probably involved, adding to the damage caused by looting for financial gain. Butterlin gave a paper detailing the plight of Mari at the International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East conference in Munich two weeks ago, to general dismay. Sadly, the palace chapel and all the royal reception rooms are now a mass of huge looters pits.

“Given the wonders of the palace of Mari and the importance of this site, it’s disappointing that the destruction of the palace and the plundering of the site in search of tablets and other saleable objects hasn’t received more attention. The first explanation is that cultural destruction in the Middle East has been so widespread in recent years that it’s ceased to be news-worthy in all but the most extreme cases, which is a depressing thought. A second disadvantage Mari has over more high-profile sites, such as Palmyra, is that its buildings were made of mud, and not the classical stonework which produces photogenic ruins and screams its artistic worth to a general audience. Nevertheless, Mari deserves to be considered as a loss on the same scale as any of the more celebrated sites to have suffered during the Isis conflict. “

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024