Home | Category: Babylonians and Their Contemporaries / Hittites and Phoenicians / Languages and Writing / Canaanites and Early Biblical Peoples / Canaanites and Early Biblical Peoples / Language and Hieroglyphics

WORLD’S OLDEST ALPHABETIC WRITTEN LANGUAGES

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: General scholarly agreement maintains that our oldest examples of alphabetic writing comes from the Sinai Peninsula and Egypt and can be dated to the nineteenth century BCE. These important inscriptions were discovered in 1998 in western Egypt and were published by a team led by Yale Egyptologist John Darnell. It’s clear that at some point alphabetic writing moved from Egypt to ancient Palestine but — until the early the 2020s — the earliest examples of alphabetic writing from the Levant were dated to the thirteenth or twelfth century BCE, some six hundred years after the Egyptian examples. How and under what circumstances the alphabet was moved from Egypt to Israel was anyone’s best guess. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, April 25, 2021]

Though there is considerable debate, some scholars hypothesized that the alphabet was transmitted in the twelfth century BCE, a period when there was intensive mining by Egyptians at Serabit el-Khadim in the Sinai desert. Graffiti produced by enslaved prisoners of war at the mines and found at the site led some to argue that the proto-semitic alphabet developed during a period in which Egyptians dominated the region. Prior to the 14th century BCE there were no alphabetic Palestinian inscriptions. The debate was complicated by the fact that scholars often disagreed about whether or not inscriptions were truly alphabetic (as opposed to pictographic) and to what period, exactly, they should be dated. There was a general sense, however, that the development of the alphabet should be tied to a period of Egyptian dominance.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Letter Perfect: The Marvelous History of Our Alphabet From A to Z” by David Sacks (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Story of Writing: Alphabets, Hieroglyphs & Pictograms” Illustrated by Andrew Robinson Amazon.com;

“Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet” by J. T. Hooker (French) (1990) Amazon.com;

“Script and Society: The Social Context of Writing Practices in Late Bronze Age Ugarit” by Philip J. Boyes Amazon.com;

“A Primer on Ugaritic: Language, Culture and Literature” by William M. Schniedewind, Joel H. Hunt Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Ugaritic” by John Huehnergard Amazon.com;

“Ugarit (Ras Shamra) by Adrian Curtis (1985) Amazon.com;

“The City of Ugarit at Tell Ras Shamra” by Marguerite Yon (2006) Amazon.com;

“Ugarit and the Old Testament: The Story of a Remarkable Discovery and its Impact on Old Testament Studies” by Peter C. Craigie Amazon.com;

“Ritual and Cult at Ugarit” by Dennis Pardee (2002) Amazon.com;

“Religious Texts from Ugarit” by Nicolas Wyatt Amazon.com;

Southern Sinai — Land of Turquoise and the Oldest Alphabet

Lydia Wilson wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Centuries before Moses wandered in the “great and terrible wilderness” of the Sinai Peninsula, this triangle of desert wedged between Africa and Asia attracted speculators, drawn by rich mineral deposits hidden in the rocks. And it was on one of these expeditions, around 4,000 years ago, that some mysterious person or group took a bold step that, in retrospect, was truly revolutionary. Scratched on the wall of a mine is the very first attempt at something we use every day: the alphabet. [Source: By Lydia Wilson, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2021]

“The evidence, which continues to be examined and reinterpreted 116 years after its discovery, is on a windswept plateau in Egypt called Serabit el-Khadim, a remote spot even by Sinai standards. Yet it wasn’t too difficult for even ancient Egyptians to reach, as the presence of a temple right at the top shows in the otherwise desolate, beautiful landscape.

The temple is built into the living rock, dedicated to Hathor, the goddess of turquoise (among many other things); stelae chiseled with hieroglyphs line the paths to the shrine, where archaeological evidence indicates there was once an extensive temple complex. A mile or so southwest of the temple is the source of all ancient interest in this area: embedded in the rock are nodules of turquoise, a stone that symbolized rebirth, a vital motif in Egyptian culture and the color that decorated the walls of their lavish tombs. Turquoise is why Egyptian elites sent expeditions from the mainland here, a project that began around 2,800 B.C. and lasted for over a thousand years. Expeditions made offerings to Hathor in hopes of a rich haul to take home.

Discovery of the Oldest Alphabet

Lydia Wilson wrote in Smithsonian magazine: In 1905, a couple of Egyptologists, Sir William and Hilda Flinders Petrie, who were married, first excavated the temple, documenting thousands of votive offerings there. The pair also discovered curious signs on the side of a mine, and began to notice them elsewhere, on walls and small statues. Some signs were clearly related to hieroglyphs, yet they were simpler than the beautiful pictorial Egyptian script on the temple walls. The Petries recognized the signs as an alphabet, though decoding the letters would take another decade, and tracing the source of the invention far longer. [Source: By Lydia Wilson, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2021]

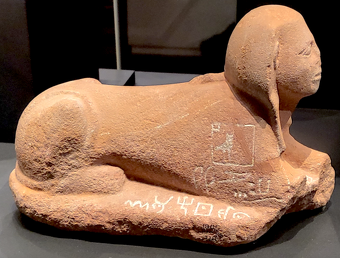

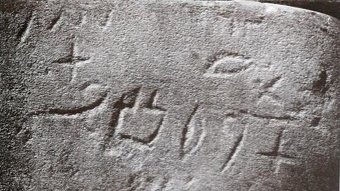

“The Flinders Petries brought many of the prizes they had unearthed back to London, including a small, red sandstone sphinx with the same handful of letters on its side as those seen in the mines. After ten years of studying the inscriptions, in 1916 the Egyptologist Sir Alan Gardiner published his transcription of the letters and their translation: An inscription on the little sphinx, written in a Semitic dialect, read “Beloved of Ba’alat,” referring to the Canaanite goddess, consort of Ba’al, the powerful Canaanite god.

“For me, it’s worth all the gold in Egypt,” the Israeli Egyptologist Orly Goldwasser said of this little sphinx when we viewed it at the British Museum in late 2018. She had come to London to be interviewed for a BBC documentary about the history of writing. In the high-ceilinged Egypt and Sudan study room lined with bookcases, separated from the crowds in the public galleries by locked doors and iron staircases, a curator brought the sphinx out of its basket and placed it on a table, where Goldwasser and I marveled at it. “Every word we read and write started with him and his friends.” She explained how miners on Sinai would have gone about transforming a hieroglyph into a letter: “Call the picture by name, pick up only the first sound and discard the picture from your mind.” Thus, the hieroglyph for an ox, aleph, helped give a shape to the letter “a,” while the alphabet’s inventors derived “b” from the hieroglyph for “house,” bêt. These first two signs came to form the name of the system itself: alphabet. Some letters were borrowed from hieroglyphs, others drawn from life, until all the sounds of the language they spoke could be represented in written form.

Use and Spread of the Oldest Alphabet

Lydia Wilson wrote in Smithsonian magazine: The temple complex detailed evidence of the people who worked on these Egyptian turquoise excavations in the Sinai. The stelae that line the paths record each expedition, including the names and jobs of every person working on the site. The bureaucratic nature of Egyptian society yields, today, a clear picture of the immigrant labor that flocked to Egypt seeking work four millennia ago. As Goldwasser puts it, Egypt was “the America of the old world.” We can read about this arrangement in Genesis, when Jacob, “who dwelt in the land of Canaan” — that is, along the Levant coast, east of Egypt — traveled to Egypt to seek his fortune. Along with shepherds like Jacob, other Canaanites ended up mining for the Egyptian elites in Serabit, some 210 miles southeast by land from Memphis, the seat of pharaonic power. [Source: By Lydia Wilson, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2021]

“Religious ritual played a central role in inspiring foreign workers to learn to write. After a day’s work was done, Canaanite workers would have observed their Egyptian counterparts’ rituals in the beautiful temple complex to Hathor, and they would have marveled at the thousands of hieroglyphs used to dedicate gifts to the goddess. In Goldwasser’s account, they were not daunted by being unable to read the hieroglyphs around them; instead, they began writing things their own way, inventing a simpler, more versatile system to offer their own religious invocations.

“The alphabet remained on the cultural periphery of the Mediterranean until six centuries or more after its invention, seen only in words scratched on objects found across the Middle East, such as daggers and pottery, not in any bureaucracy or literature. But then, around 1200 B.C., came huge political upheavals, known as the late Bronze Age collapse. The major empires of the near east — the Mycenaean Empire in Greece, the Hittite Empire in Turkey and the ancient Egyptian Empire — all disintegrated amid internal civil strife, invasions and droughts. With the emergence of smaller city-states, local leaders began to use local languages to govern. In the land of Canaan, these were Semitic dialects, written down using alphabets derived from the Sinai mines. [Source: By Lydia Wilson, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2021]

“These Canaanite city-states flourished, and a bustling sea trade spread their alphabet along with their wares. Variations of the alphabet — now known as Phoenician, from the Greek word for the Canaanite region — have been found from Turkey to Spain, and survive until today in the form of the letters used and passed on by the Greeks and the Romans.

Did Illiterate People Create the Oldest Alphabet

Lydia Wilson wrote in Smithsonian magazine: ““In the century since the discovery of those first scratched letters in the Sinai mines, the reigning academic consensus has been that highly educated people must have created the alphabet. But Goldwasser’s research is upending that notion. She suggests that it was actually a group of illiterate Canaanite miners who made the breakthrough, unversed in hieroglyphs and unable to speak Egyptian but inspired by the pictorial writing they saw around them. In this view, one of civilization’s most profound and most revolutionary intellectual creations came not from an educated elite but from illiterate laborers, who usually get written out of history.[Source: By Lydia Wilson, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2021]

“Pierre Tallet, former president of the French Society of Egyptology, supports Goldwasser’s theory: “Of course [the theory] makes sense, as it is clear that whoever wrote these inscriptions in the Sinai did not know hieroglyphs,” he told me. “And the words they are writing are in a Semitic language, so they must have been Canaanites, who we know were there from the Egyptians’ own written record here in the temple.”

“There are doubters, though. Christopher Rollston, a Hebrew scholar at George Washington University, argues that the mysterious writers likely knew hieroglyphs. “It would be improbable that illiterate miners were capable of, or responsible for, the invention of the alphabet,” he says. But this objection seems less persuasive than Goldwasser’s account — if Egyptian scribes invented the alphabet, why did it promptly disappear from their literature for roughly 600 years?

“Besides, as Goldwasser points out, the close connection between pictograms and text would seem to be evident all around us, even in our hyper-literate age, in the form of emojis. She uses emojis liberally in her emails and text messages, and has argued that they fulfill a social need the ancient Egyptians would have understood. “Emojis actually brought modern society something important: We feel the loss of images, we long for them, and with emojis we have brought a little bit of the ancient Egyptian games into our lives.”

Canaanite — the World’s Oldest Alphabetic Written Language?

Drawings of the first known Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions, as published in "The Egyptian Origin of the Semitic Alphabet", by Alan H Gardiner

The written language of the Canaanites preceded Latin, making it the oldest written language with an alphabet in history, as it was the "first alphabet in the world from which most of the modern alphabets, including the Latin alphabet, descend," Daniel Vainstub, an epigrapher at Ben-Gurion University in Israel, told Live Science. [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, November 14, 2022]

According to Smithsonian magazine: The Canaanite writing system generally agreed to have emerged between 1900 and 1400 B.C. — offered a clear improvement in user-friendliness compared with earlier pictorial scripts such as cuneiform and hieroglyphics. With their simple association between a character and a specific sound, Canaanite writing proved the basis from which modern Western alphabets evolved. [Source: Chris Klimek, Smithsonian magazine, March 2023]

In 2016, a team of researchers, led by professor Yosef Garfinkel from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, unearthed an ivory comb from an archaeological site at Tel Lachish, about 35 miles southwest of Jerusalem. that was later discovered to some of the world’s oldest alphabetic writing on it according to a study published in the Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology. The tiny comb is only about four centimeters (1.5 inches) wide and 2.5 centimeters (1 inch tall). The teeth on the top have broken off, but some remain on the bottom, photos show. When it was first found is was classified as a bone. Preserved remains of lice were found on the comb’s teeth, indicating its purpose, the study said. [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, November 9, 2022]

Analyzing the comb’s material revealed it was made of expensive elephant ivory, likely imported from Egypt, professor Rivka Rabinovich from the Hebrew University and professor Yuval Goren from Ben Gurion University said. On the comb’s rough surface, 17 tiny letters were engraved. They came from the earliest-known alphabet created by Canaanites around 1800 B.C.,

See Separate Article: CANAANITE LANGUAGE AND THE WORLD'S OLDEST ALPHABETIC WRITING africame.factsanddetails.com

Ugarit Alphabet

According to the Guinness Book of Records, the earliest example of alphabetic writing was a clay tablet with 32 cuneiform letters found in Ugarit, Syria and dated to 1450 B.C. The Ugarits condensed the Eblaite writing, with its hundreds of symbols, into a concise 30-letter alphabet that was the precursor of the Phoenician alphabet.

The Ugarites reduced all symbols with multiple consonant sounds to signs with a single consent sound. In the Ugarite system each sign consisted of one consonant plus any vowel. That the sign for “p” could be “pa," “pi” or “pu." Ugarit was passed on to the Semitic tribes of the Middle east, which included the Phoenician, Hebrews and later the Arabs.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The population was mixed with Canaanites (inhabitants of the Levant) and Hurrians from Syria and northern Mesopotamia. Foreign languages written in cuneiform at Ugarit include Akkadian, Hittite, Hurrian, and Cypro-Minoan. But most important is the local alphabetic script that records the native Semitic language "Ugaritic." From evidence at other sites, it is certain that most areas of the Levant used a variety of alphabetic scripts at this time. The Ugaritic examples survive because the writing was on clay using cuneiform signs, rather than drawn on hide, wood, or papyrus. While most of the texts are administrative, legal, and economic, there are also a large number of literary texts with close parallels to some of the poetry found in the Hebrew Bible” [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "Ugarit", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

See Separate Article: UGARIT, ITS EARLY ALPHABET AND THE BIBLE africame.factsanddetails.com

Ugaratic chart of letters

Phoenician Alphabet

The Phoenicians spoke a Semitic language. They are credited with inventing letters and the alphabet. Their alphabet caught on because it was practical for trade an it could be learned quickly by other peoples. Their system of writing was far simpler than Egyptian hieroglyphics and Mesopotamian cuneiform. It democratized writing, making it something that everyone could understand rather than a small elite.

The Phoenician alphabet had 22 letters, each for sound rather than a word or phrase. It provided the basis for the Hebrew and Arabic alphabet as well as the Greek alphabet which gave birth to the Latin alphabet which beget the modern alphabet. The Phoenician alphabet is the ancestor of all European and Middle Eastern alphabets as well as ones in India, Southeast Asia, Ethiopia and Korea. The English alphabet evolved from the Latin, Roman, Greek and ultimately the Phoenician alphabets. The letter "O" has not changed since it was adopted into the Phoenician alphabet in 1300 B.C.

Phoenician writing was read from right to left like Hebrew and Arab, but the opposite direction of English. The major difference between the 22-letter Phoenician alphabet and the one we use today is that the Phoenician alphabet had no vowels. Its genius was its simplicity.

Under the Phoenician system a two syllable word like drama written could have at least nine different pronunciations — 1) drama, 2) dramu, 3) drami, 4) drima, 5) drimu, 6) drimi, 7) druma, 8) drumu, 9) drumi — because the vowels sounds were not specified. Most people who could read could recognize which word was meant and which vowel sounds were present by the signs that were given. Even so there was lots of potential for confusion. The Greeks introduced vowels, which cleared up the confusion.

See Separate Article: PHOENICIAN ALPHABET AND OTHER EARLY ALPHABETS factsanddetails.com

Phoenician Alphabet

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons

Text Sources: John R. Abercrombie, University of Pennsylvania, Department of Religious Studies, University of Pennsylvania; James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), Princeton, Boston University, bu.edu/anep/MB.html; “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024