Home | Category: Late Stone Age and Copper and Bronze Age / Canaanites and Early Biblical Peoples / Canaanites and Early Biblical Peoples

FOOD IN CANAAN AND ANCIENT ISRAEL

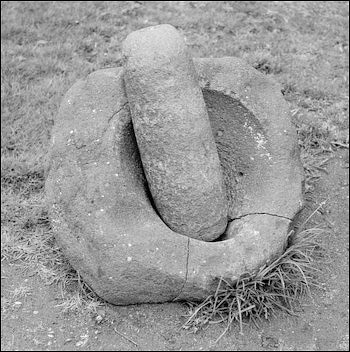

grinding stone from Tel Megiddo

According to the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology: “In the Bronze and Iron Age, bread was the staple food. Since it was prepared almost every day, bread-making was one of the main activities of a household. People in Canaan and Ancient Israel consumed between 330 - 440 lbs. of wheat and barley per year. An individual typically consumed 50 - 70 percent of calories from these cereals — mostly eaten in the form of bread. [Source: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology |~|]

“The grinding of grain was done by hand, using a quern: this consisted of a fixed lower stone, called a metate, and a moveable upper stone or mano. The quern was made of basalt, a course volcanic stone, which was preferred for the process because of its rough surface and relatively light weight. The grain was ground on the course surface to break down the soft center of the kernel into flour. It was a very laborious process and had the disadvantage of producing basalt grit which got into the bread and gradually wore down the teeth. |~|

“Bread was baked in small domed clay ovens, or tabun. Archaeologists have excavated ancient ovens which were usually made by encircling clay coils or from re-used pottery jars. The oven was heated on the interior using dung for fuel; flat breads were baked against the interior side walls. Grain could also be eaten as a porridge or steeped in water and fermented to make beer. The fermented liquid was poured through ceramic strainers to separate the beer from the barley sediment.

“Meat was a luxury which did not normally form part of the diet because animals could be more profitably be used to produce other commodities. Meat from goats, sheep and cattle was normally eaten at sacrificial feasts and as part of the entertainment of a special guest. Meat was also obtained from birds. The chicken may not have been introduced into the southern Levant until the later Iron Age. Seafood was rare for the Israelites as they lacked access to the Mediterranean for part of their history. A limited variety of fruits and vegetables was also eaten including dates, pomegranates, figs, grapes, olives, legumes, onions, leeks, beans and lentils. Seasonings included salt, garlic, aniseed, coriander, cumin, dill, thyme, mint, nuts and honey.” |~|

RELATED ARTICLES:

CANAANITES: WHO THEY WERE, THEIR CITIES AND DEPICTIONS OF THEM IN THE BIBLE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITES: HISTORY, ORIGINS, INVASIONS, BATTLES factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITE LANGUAGE AND THE WORLD'S OLDEST ALPHABETIC WRITING africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITE RELIGION: TEMPLES, OFFERINGS, RITUALS AND CULTS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITE GODS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITE TOMBS AND BURIAL PRACTICES africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITE HOUSES, BUILDINGS AND SETTLEMENTS factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITE LIFE: TOOLS, EVERYDAY ITEMS AND MONEY africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITE ART, CRAFTS, MUSIC AND GAMES africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Dawn of Israel: A History of Canaan in the Second Millennium BCE”

by Lester L. Grabbe Amazon.com ;

“The Canaanites: Their History and Culture from Texts and Artifacts” by Mary Ellen Buck

Amazon.com ;

“Israelite Religions: An Archaeological and Biblical Survey”

by Richard S. Hess Amazon.com ;

“Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan” by John Day , Andrew Mein, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Stories from Ancient Canaan” by Michael D. Coogan and Mark S. Smith Amazon.com ;

“Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, Philistines, and Early Israel, 1300-1100 B.C.E.” by Ann E Killebrew Amazon.com ;

“Hazor: Canaanite Metropolis:Israelite City” by Amnon Ben-Tor Amazon.com ;

“The Bible Unearthed” by I. Finkelstein and N. Asher Silberman Amazon.com ;

“Archaeology of the Bible: The Greatest Discoveries From Genesis to the Roman Era”

by Jean-Pierre Isbouts Amazon.com ;

“Unearthing the Bible: 101 Archaeological Discoveries That Bring the Bible to Life” Amazon.com ;

“Zondervan Handbook of Biblical Archaeology: A Book by Book Guide to Archaeological Discoveries Related to the Bible” by J. Randall Price and H. Wayne House Amazon.com ;

“NIV, Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible (Context Changes Everything) by Zondervan, Craig S. Keener Amazon.com ;

“Egypt, Canaan and Israel in Ancient Times” by Donald Redford Amazon.com ;

“Biblical Diet”

Since the 1990s, in the Neot Kedumim nature reserve between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, Israel’s most well-known food archaeologist Tova Dickstein has been growing a variety of plants and foodstuffs as part of her effort to examine the ingredients and cooking methods of the so-called, millennia-old, ‘biblical diet’. Shira Rubin wrote for the BBC: At the time of the Bible, ancient Israel was famed for its wine, honey and pomegranates, along with its olive oil, which was used extensively both raw and for cooking the occasional meat and the more frequent stews of legumes like lentils and barley. Dickstein, a secular Israeli, is fascinated by the Bible and its sparse but deeply poetic references to food...She, along with a new generation of academics and chefs, are cooking with ancient grains and herbs, using what they believe are original recipes. [Source: Shira Rubin, BBC, May 10, 2018]

Dickstein has worked with fellow Israeli and Palestinian food researchers to decrypt the histories and evolutions of local foods, like wild chicory or ancient grains such as millet and barley. Dickstein relies on the Hebrew Bible, a labyrinthine piece of literature teeming with ambiguity. To interpret the recipes, she cross-checks the Bible with modern people who are replicating or producing some version of the biblical diet. For example, Ezekiel bread features as a rare example of a biblical recipe, in the Book of Ezekiel. There, God instructs the Hebrew prophet Ezekiel: “Take you also to you wheat, and barley, and beans, and lentils, and millet, and fitches, and put them in one vessel, and make you bread thereof...”

Today, ‘Ezekial Bread’ is sold in health-food stores across the world, billed as a kind of carb superfood. But Dickstein believes it was never a bread at all, but in its original form consisted of fava beans, millet and nutrient-rich seeds, served alongside an ancient kind of barley bread. “The word ‘bread’ in biblical Hebrew translates to ‘hearty stew,” Dickstein explained. She says her suspicions were confirmed on a visit to modern Crete, where she found a similar dish made of precisely those ingredients. It’s known as ‘palikaria’ and is served during feast times, including on 5 January, ahead of the Christian Epiphany holiday, as well as during Lent, Dickstein says. She believes the dish was originally a Cretan food, brought over to Israel by the Minoans, an Ancient Greek civilisation whom archaeologists believe were among the most influential outside civilisations in the ancient Israelite city-state of Canaan, and whom Ezekiel actually mentions encountering in the Bible.

Winery Discovered in Canaanite Palace

In May 2016, Science Daily and the University of Haifa reported: “For the first time in excavations of ancient Near Eastern sites, a winery has been discovered within a Canaanite palace. The winery produced high-quality wine that helped the Canaanite ruling family to impress their visitors — heads of important families, out-of-town guests, and envoys from neighboring states. “All the residents of the Canaanite city could produce simple wine from their own vineyards. But just before it was served, the wine we found was enriched with oil from the cedars of Lebanon, tree resin from Western Anatolia, and other flavorings, such as resin from the terebinth tree and honey. That kind of wine could only be found in a palace,” says Prof. Assaf Yasur-Landau of the Maritime Civilizations Department at the University of Haifa, one of the directors of the excavation. The full findings of the 2015 excavation season was presented at the conference “Excavations and Studies in Northern Israel,” which took place at the University of Haifa, and in May 16 at the Oriental Institute in Chicago. [Sources: Science Daily, University of Haifa, May 2, 2016 /=/]

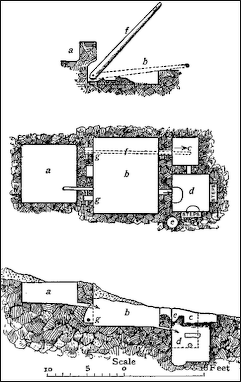

ancient Palestine wine press

“The excavations at the Canaanite palace at tel Kabri, which was established around 3,850 years ago during the Middle Bronze Age (2200 - 1570 B.C.) (around 1950-1550 ), are continuing to yield surprises and to provide evidence of a connection between wine, banquets, and power in the Canaanite cities. Two years ago, around 40 almost-complete large jars were found in one of the rooms, and chemical analysis proved that they were filled with wine with special flavorings, such as terebinth resin, cedar oil, honey, and other plant extracts. “This was already a huge quantity of jars to find in a palace from the Bronze Age, and we were really surprised to find such a treasure,” says Prof. Yasur-Landau, who is directing the excavation together with Prof. Eric Cline of George Washington University, and Prof. Andrew Koh of Brandeis University. /=/

“In this early excavation the researchers already found openings leading into additional rooms. They devoted 2014 to analyzing the findings from the excavation, particularly the chemical analysis of the wine residues. During the 2015 excavation season, conducted in the summer, the researchers returned to the ancient rooms, not knowing what awaited them. The northern opening led to a passage to another building. Both sides of the passage were lined with “closets” containing additional jars. The southern opening led to a room that was also full of jars buried under the collapsed walls and roof. This was clearly an additional storeroom. “We would have happily called it a day with this discovery, but then we found that this storeroom also had an opening at its southern end leading to a third room that was also full of shattered jars. And then we found a fourth storeroom” relates Prof. Yasur-Landau. /=/

“But the surprises kept on coming. As in the previous seasons, each of the new jars was sampled in order to examine its contents. The initial results showed that while all the jars in the first storeroom were filled with wine, in the other storerooms some of the jars contained wine, others appear to have been rinsed clean, while others still contained only resin, without wine. “It seems that some of the new storerooms were used for mixing wines with various flavorings and for storing empty jars for filling with the mixed wine. We are starting to think that the palace did not just have storerooms for finished produce, but also had a winery where wine was prepared for consumption.” Prof. Yasur-Landau added that this is the first time that a winery has been found in a palace from the Middle Bronze Age. /=/

“He adds that the new findings, together with the evidence from previous years of select parts of sheep and goats, have strengthened our understanding of the way rulers used splendid banquets to strengthen their control. “In this period it was not normal practice to mix wine beforehand. Accordingly, in order to provide guests with high-quality wines, the palace itself must have had a winery where they made prestigious wine and served it immediately to guests. These splendid banquets, which in addition to wine also included choice joints of sheep and goat, were the way rulers stayed in touch with their ‘electorate’ at the time — not only the heads of important extended families, but also guests from other cities and foreign envoys.” On the basis of ancient Ugaritic documents, the value of the wine in the storeroom can be estimated at a minimum of 1,900 silver shekels — an enormous sum that would have been sufficient, for example, to purchase three merchant ships. By way of comparison, an ordinary laborer in the same period would have to work for 150 years to earn this sum.” /=/

Animals in Canaan and Ancient Israel

According to the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology: “People in the Bronze and Iron Age lived in close contact with domestic animals. Animals provided food, and their care and feeding was an investment and a hedge against hard times. Sheep and goats were the principal herd animals: they are mobile, resilient in drought and provide meat, milk, wool, manure, and leather. Although cattle provide most of these same products and also can be used for plowing, they are not as well adapted to dry conditions and broken terrain. [Source: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology |~|]

“Iron Age houses usually included space for stabling animals. Small flocks were housed in and around the village, but large flocks had to travel considerable distances to find sufficient water and pasture. For at least part of each year, full-time shepherds were nomadic... Pigs were rare in the Iron Age. Beginning at the end of the Middle Bronze Age, the raising of pigs declined steadily. Pigs were costly to feed and do not provide milk, hair or wool. The avoidance of pork probably was already a widespread cultural pattern before the dietary prohibition of Leviticus 11:7 in the Old Testament. In the Hellenistic period (333 - 63 BCE), when pork consumption once again became popular, this long-standing regional pattern also became a means of marking an ethnic division between Jews and Greeks.” |~|

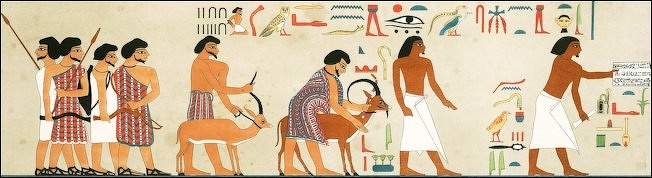

Canaanites in the Beni Hassan tombs

John R. Abercrombie of the University of Pennsylvania wrote: “Although there is a wide variety of animal bones in archaeological contexts, the vast majority are from the primary herd animals, sheep and goats. Cattle, which require more pasture land and demand abundant water, were a secondary herd animal throughout the period, and their bones, though common, occur less frequently. One finds a wide variety of remains from other animals in ancient sites: pigs, horses, donkeys, oxen, camels, dogs, fallow deer, hippopotami, birds, fish, etc. [Sources: John R. Abercrombie, University of Pennsylvania, James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), Princeton, Boston University, bu.edu/anep/MB.html |*|]

“Animal bones are found in domestic and other contexts. Swine astragali, surprisingly, appear in tombs in the Iron Age. Right Forelegs or astragali of immature goats and sheep are common in pits near sites interpreted as bamot or temples. At the end of Middle Bronze, complete skeleton of donkeys appear in a few communal burials. More common in Middle Bronze Age (2200 - 1570 B.C.) tombs, though, are joints from goats, sheep and cattle. |*|

“A detailed study of animal bones at Beersheba provided some interesting observations about exploitation of animals. Sheep/goats were by far the most common herd animal in all strata. Cattle were also well represented but at a lower percentage than sheep/goats (ratio: 3 to 1); however, if one takes into account animal size it is clear that cattle figured more promptly in the diet than sheep. Generally the bones from all three came from the right foreparts of the animal. Skulls were generally found in fragments which suggests that the brain may have been eaten. Finally, there is a steady increase in the number of remains from juvenile specimens thus suggesting a growth in food supply throughout the period. |*|

3,500-Year-Old Opium Found in Ancient Canaanite Grave

In September 2022, scientists from Israel say they have found evidence that the Canaanites used opium as an offering for the dead, as far back a 14th century B.C. Reuters reported: Opium traces have been discovered in Israel in vessels used in burial rituals by the ancient Canaanites, providing one of the world's earliest evidences of use of the drug. Discovered in a 2012 excavation in Tel Yehud in central Israel, the Late Bronze Age vessels, shaped like upside-down poppy flowers, were found at Canaanite graves, where they were likely used in burial ceremonies and for offerings for the dead in the afterlife, researchers said. [Source: [Source: Reuters, September 20, 2022]

A new joint study by the Weizmann Institute of Science, Tel Aviv University and the Israel Antiquities Authority, analysed organic residue in eight of the vessels and found that it was opium, some of which was produced locally and some in Cyprus. The findings date back to the 14th century B.C., the researchers said in their study, published in the Archaeometry journal. Precisely how opium was used by the Canaanites in their burial rituals, remains unknown, the researchers said. "It may be that during these ceremonies, conducted by family members or by a priest on their behalf, participants attempted to raise the spirits of their dead relatives in order to express a request, and would enter an ecstatic state by using opium," said Ron Beeri of the Israel Antiquities Authority. "Alternatively, it is possible that the opium, which was placed next to the body, was intended to help the person’s spirit rise from the grave in preparation for the meeting with their relatives in the next life," Beeri said.

According to Live Science: Archaeologists from the Israel Antiquities Authority and the Weizmann Institute of Science found the opium-laced pottery, alongside the skeletal remains of a male who died between 40 and 50 years of age, in 2017, according to a study published July 2, 2022 in the journal Archaeometry. "There was a hypothesis in 2017 that because some of the jugs resembled poppies, that they might contain opium," Vanessa Linares, a doctoral candidate at Tel Aviv University and the study's lead author, told Live Science. "We found that was the case and that opium was contained inside some of the vessels."

While it's not clear why opium was part of this particular burial, Linares said researchers have several theories based on historical documentation from other ancient civilizations around the world. "According to the historical and written record, we see that Sumerian priests used opium to reach a higher state of spirituality, while the Egyptians reserved opium for warriors as well as priests, possibly using it not only to have a psychoactive effect but also for medicinal processes, since its main compound is morphine, which is used to help with pain," Linares said. "Perhaps it was also there as an offering for the gods, and maybe they thought that the deceased would need it in the afterlife," she added. "I think we can make a lot of speculations and suggestions for why it was there." [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, September 24, 2022]

See Earliest Evidence of the Opium Trade — from Cyprus under LIFE, ART AND CULTURE IN ANCIENT CYPRUS africame.factsanddetails.com

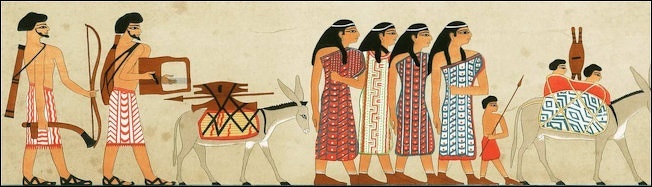

Canaanites in the Beni Hassan tombs

Clothes, Weaving and Textiles in Canaan and Ancient Israel

According to the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology: “Most families in the Bronze and Iron Age wove their own cloth and made their own clothing. Like breadmaking, this was an activity that figured prominently in the daily lives of women. In antiquity, the southern Levant was famous for the weaving of luxurious patterned and colored textiles. [Source: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology |~|]

“For average households, weaving was a means of producing simple everyday garments. Excavators at Tell es- Sa'idiyeh discovered burned wooden frames of looms and rows of clay loom weights in many houses. These looms were "warp-weighted": the threads on the long axis of the weave (the warp) were suspended vertically with weights. The passing of thread (the weft) horizontally in and out of the warp created the weave. |~|

“The principal fibers used for weaving were sheep wool, goat hair, and flax - - a fibrous plant used to make linen. Before it could be formed into a thread, wool had to be washed, picked clean and combed straight. Then the fibers were spun to entwine them and draw them into a long, even strand. Usually a spindle, a weighted stick suspended in the air and spun on the thigh, was used (the use of the spindle is represented through a model in the exhibit). The spun fibers were then stretched upon the loom to weave into garments. |~|

“Weaving was time consuming, but the tasks allowed for socializing, and could be taken up and put down as needed. Therefore, weaving activities could be matched to the rhythm of the house. |~|

“Archaeology has revealed some information on the manner in which Canaanites and Israelites would adorn themselves. It is apparent that both women and men wore make-up and jewelry. Kohl, a black eye-paint derived from antimony, was the most common cosmetic product. Make-up was applied by means of a stick or small spoon and stored in shallow bowls. Men and women alike would scent themselves with perfumed oils. |~|

“Clothing was a principal indication of status. In Egyptian art, Canaanite nobles are shown wearing elaborately patterned woven clothing. In the Iron Age, fringed garments were associated with special status. Elite clothing was often multi-layered and required fasteners. Toggle pins were used until the later Iron Age when fibulae, an ancient version of the safety pin, spread across the Near East. Both Canaanites and Israelites wore a frontlet, or headband, on the forehead.” |~|

Cosmetic Palettes, Combs and Wine Sets

John R. Abercrombie of the University of Pennsylvania wrote: “Stone cosmetic palettes, flat bowls, date to the ninth-eighth centuries B.C.. Few are undecorated and most have incised lines or concentric circles on the flat lip. Occasionally evidence of blue makeup has been found in the incised decorations. [Sources: John R. Abercrombie, University of Pennsylvania, James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), Princeton, Boston University, bu.edu/anep/MB.html |*|]

“Bronze bowls, the drinking goblets for wine sets, and even wine strainers occur in some early the early Iron Age contexts as well as Late Bronze Age tombs: Tomb 7 (Beth Shan). Similar bronze vessels including wine set were recently uncovered by the British Museum's more recent excavation of Tell es-Sa'idiyeh and are further more contemporary evidence for the smelting of bronze in the Transjordan (1 Kings 7:46). |*|

“Wooden single-teeth combs with scalloped tops were uncovered in numerous tombs at Jericho (Tell es-Sultan). These combs are found among the remains of woven baskets or wooden cosmetic boxes. Occasionally combs are found in the vicinity of the skull (especially infant and child burials), thus suggesting that they were worn as decoration at least in death. |*|

See the Alphabet Lice Comb Under CANAANITE LANGUAGE AND THE WORLD'S OLDEST ALPHABETIC WRITING africame.factsanddetails.com

Jewelry in Middle Bronze Age (2200 - 1570 B.C.) Canaan

John R. Abercrombie of the University of Pennsylvania wrote: ““TOGGLE PINS: Elongated copper toggle pins do occur in a few the early Middle Bronze Age burials in Syria and northern Palestine. Such pins are narrow and much longer than examples from later perods. The tie hole is located quite close to the pin's head. No examples of this type of pin can be cited from Beth Shan and Gibeon (el Jib). No examples of early Middle Bronze Age beads were able to be located in the University's collection though records indicate early Middle Bronze Age beads were collected from Tomb 32 Gibeon (El Jib). A fine collection of barrel-shaped and spherical beads were uncovered at Jericho (Tell es-Sultan). [Sources: John R. Abercrombie, University of Pennsylvania, James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), Princeton, Boston University, bu.edu/anep/MB.html |*|]

“The typical garment fastener of the Bronze Age is often found in tombs. Various types of toggle pins are known, and the tombs at Gibeon (el Jib) generally illustrate the types used in MBIIB rather than MBIIC. Almost all toggle pins of this period are cast in bronze rather than precious metals as is more common in Late Bronze Age . They also lack knob or nail heads as well as etched designs, features of Late Bronze pins. |*|

Canaanite Jewelry

“Gold sheet pendants, bands and even dagger-shaped sheets depicting goddesses (?), are part of the high art of this period. Many pieces appear to be adornment items especially the pendants and bands. Use of gold foil sown into headdresses seems evident from a number of burials at Megiddo dated to the beginning of the Late Bronze Age. The finest collection of such forms occurs in the courtyard cemetery and hoards at Tell el-Ajjul, ancient Gaza. Only scattered examples from contemporary remains can be cited from other excavations, and it is not until the Late Bronze Age (1570 - 1200 B.C.) that one finds such quality work throughout the region. Petrie's discovery at Ajjul, thus, remains one of the great discoveries in the high art of this region. |*|

Scarabs become the signet item of choice in the second millennium replacing the cylinder seal. The earliest types of scarabs tend to be slightly smaller than most later examples; less detailed designs; and have. smooth, undecorated backs. Rapidly in the 12th Dynasty, the scarab designed developed as this mostly amuletic charm became more common in tombs and on tells. A particular style of scarab, often called Hyksos, is easily identifiable by designs on the front, or face. The border around the scarab's face may have geometric design, such as concentric circles, swirls, cross-hatching and volutes. Hieroglyphics tend to be gibberish, non-sensical or simplistic expressions wishing health for the wearer or a god. Such wishes seem to indicate that the scarab was also considered to be a talisman, a function that seems a characteristic use of later scarabs. Scarabs with pharonic titles are extremely rare in the Middle Bronze Age. An pharonic scarab of Sesostris III was found in Stratum IX, Beth Shan (Late Bronze Age A). ||

“Scarabs in this period are generally found near the neck or fingers in the few undisturbed burials. Occasionally scarabs are found suspended, it appears, from toggle pins. The location of the scarabs tend to suggest that even very early they functioned more as amuletic charms than signet items. |*|

Canaanite Jewelry in the Bible

Genesis 24:22 When the camels had done drinking, the man took a gold ring weighing a half shekel, and two bracelets for her arms weighing ten gold shekels, [Source: John R. Abercrombie, Boston University, bu.edu, Dr. John R. Abercrombie, Department of Religious Studies, University of Pennsylvania]

Ezekial 16:12 And I put a ring on your [female] nose, and earrings in your ears, and a beautiful crown upon your head.

Middle Bronze Age jewelry from Canaan

Exodus 35:22 So they came, both men and women; all who were of a willing heart brought brooches and earrings and signet rings and armlets, all sorts of gold objects, every man dedicating an offering of gold to the LORD.

Numbers 31:50 And we have brought the LORD's offering, what each man found, articles of gold, armlets and bracelets, signet rings, earrings, and beads, to make atonement for ourselves before the LORD."

Judges 8:24 And Gideon said to them, "Let me make a request of you; give me every man of you the earrings of his spoil." (For they had golden earrings, because they were Ish'maelites.)

Judges 8:26 And the weight of the golden earrings that he requested was one thousand seven hundred shekels of gold; besides the crescents and the pendants and the purple garments worn by the kings of Mid'ian, and besides the collars that were about the necks of their camels. Isaiah 3:18-21 In that day the Lord will take away [from the daughters of Zion] the finery of the anklets, the headbands, and the crescents; the pendants, the bracelets, and the scarfs; the headdresses, the armlets, the sashes, the perfume boxes and the amulets; the signet rings and noise rings;

Prov 11:22 Like a gold ring in a swine's snout is a beautiful woman without discretion.

Jewelry in Late Bronze Age (1570 - 1200 B.C.) Canaan

Abercrombie wrote: “Jewelry styles increase prodigiously in the Late Bronze Age. Paste and Lotus-seed carnelian beads, more intricate toggle pins, royal scarabs, and theophoric and other types pendants/amulets occur throughout the lands that Egyptians called Djahi, or Palestine. Some pieces were obviously manufactured in Egypt, though many more appear to be local imitations of Egyptian prototypes. [Sources: John R. Abercrombie, University of Pennsylvania, Department of Religious Studies, University of Pennsylvania; James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), Princeton, Boston University, bu.edu/anep/MB.html |*|]

“By the late thirteenth century, Egyptian amulets appear in the richer burials and are commonly found in altar areas in temples. Archaeologists hypothesize that these artifacts were either votive objects offered to the gods and/or decorated statuary of particular deities. Some of the more common types of amulets/pendants include depictions of deities (Ptah Sokar, Bes, Aegis of Bast, Sacred eye of Horus), animals (fish, hippopotamus), flora, hieroglyphs and geometric forms. Most amulets and pendants are faience, although the few locally made examples are gold, bone, shell and metal. Plaque amulets become more common place towards the end of the period and continue into the early Iron Age period. |*|

“Beads, which are extremely rare in the Middle Bronze II, increase in number and types as one moves from the the early Late Bronze to Late Bronze Age . The dramatic increase in beads, both number and type, perhaps is a direct result of the invention of glass around 1600. Spherical, cylindrical, barrel and disc-shaped beads are made of paste or faience, though stone and metal beads continue to be produced throughout the period and into the Iron Age. Generally bead shapes prove an unreliable indicator of date. A few bead forms, however, are distinctive and can be placed into specific chronological periods. The gold palmette bead is well known from Egyptian sites, but rare in Palestine (Deir el-Balah Tomb 118). A derivative form, the lily shaped pendant, is common in the Late Bronze Age . The lotus-seed carnelian bead appears in the late Late Bronze Age (Deir el-Balah Tomb 116, Tell el-Farah S Tomb 934, Beth Shemesh St. IV Pit 1005) and continues into the early Iron Age (Beth Shan Tombs 7, 66). |As the number of bead strands increases towards the end of the Bronze Age, bead spacers are employed to separate anywhere from two to almost a dozen strands of beads. Strings of beads were worn by some adult females and children either around the neck or on the wrist. |*|

Canaanite jewelry piece

The earliest type of earrings, the mulberry earring, has one or three cluster balls attached to a loop; it appears at the end of Middle Bronze IIC or the beginning of the Late Bronze and may continue to the end of the period. Later open and smaller circular earrings dominate the first part of Late Bronze Age . Towards the end of Late Bronze Age , the lunate earring with its swelling base becomes the most common form: Deir el-Balah Tomb 118, Tell el-Farah S Tombs 922, 934, Beth Shan Tomb ?, Megiddo Tombs 912B (Late Bronze) and 39 (Iron I). It continues to be the more common type of earring in Iron I. A fruit-shaped (pomegrante?) earring is much rarer and restricted, it appears, the Late Bronze Age: Deir el-Balah Tombs 116,118, Tell el-Farah S Tomb 934, and Beth Shemesh St. IV. |*|

“Thin gold, occasionally silver and rarely bronze sheets with looped ends either function as earrings or are sown into clothing. Fine collections of these delicate appliques with their floral designs or etched female heads were uncovered at Tell el-Ajjul (ancient Gaza), Lachish, Megiddo and Beth Shan. Most examples from Beth Shan date to Late Bronze Age B and are rosettes, a common floral design common on other artifacts, ivory lids, pottery, and statuary. |Foil sheets also were sown into headdresses or worn as bands around the head. Some excavators identify these frontlets as mouthpieces which were occasionally employed in an Aegean practices for sealing the lips. No known examples in Palestine proper have been found over the mouth of a deceased; however, several skeletons (Megiddo II., p.?.) have foil strips on the forehead. |*|

Continuity to the Middle Bronze Age (2200 - 1570 B.C.) can be seen in scarabs in Late Bronze I, for unlike Egypt, scarab design in Palestine does not change significantly at the beginning of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Hyksos-like scarabs continue to be produced locally in the early Late Bronze and even into Late Bronze Age . By the end of Late Bronze I, a more typical style of scarab appears and usually has the royal cartouche of an Egyptian pharaoh, more likely Thothmosis III (Mn- hpr-R'). In addition to royal scarabs, many other scarabs of the Late Bronze have expression of luck and goodwill for the bearer, thus suggesting that scarabs were becoming more amuletic in this period than in the previous Middle Bronze Age. Animal scarabs also become quite common in Late Bronze Age . A special type of scarab, the large commemorative scarab reporting special events during the pharaoh's reign (e.g. Amunhotep III), are occasionally discovered. |*|

Small finger rings are occasionally uncovered. Several faience rings from Beth Shan had a molded wadjet, or sacred eye symbol. Small and generally non-descript looped copper rings complete the corpus. Late Bronze Toggle pins are squat in comparison to Middle Bronze examples. Pins may have more elaborate heads (nail, knob head, twisted design or incised design) as well as being made from gold, electrum and, of course, bronze. Towards the end of the Bronze Age, bronze anklets are found on some adult female skeletons. The location of such anklets and armlets on figurines also confirm the decorative use of these larger bronze rings. In fact, it might be pejorative to identify some of these bangles as bracelets given that they are rarely found around the wrist and more often occur on the upper arm. |*|

Jewelry in Iron Age (1200 - 550 B.C.) Canaan

Abercrombie wrote: “Lotus-seed carnelian beads (Beth Shan Tombs 7, 66) and lunate earrings, typical forms of the the late Late Bronze Age period, occur in the early Iron Age tombs as well. Some of the more common types of amulets are the Ptah Sokar, Uraeus, and Bes. Scarabs remain the typical signet item of Iron I, though, stamp seals, which will become a dominant form in The Late Iron Age, begin to appear in burials (Tell es-Sa'idiyeh 118, Baq'ah Valley Cave A4). Gold foil fragments are thought to have been used either to seal the lips of the deceased or to be sown into headdress (that is, frontlets), much as some the early Late Bronze burials from Megiddo seem to demonstrate. [Sources: John R. Abercrombie, University of Pennsylvania, James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), Princeton, Boston University, bu.edu/anep/MB.html |*|]

Late Bronze Age silver jewelry

“The lunate earring of the Late Bronze and the early Iron Age continues, but undergoes transformation in The Late Iron Age. A tab or tassel is added to the earring in the first half of the late Iron Age. The tassel or tab becomes longer and longer, and the earring itself becomes thicker and heavier, thus reflecting more the general jewelry style of Assyria. |*|

“Bone pendants, the most common being long cylinders or minature mallets, are commonly found in tenth-seventh century remains. The pendants have a hole at one end and may be decorated with circular ring designs or incised lines. Such pendants have been found at a number of sites in Palestine. How the pendants were worn is debated.W.F. Albright suggested that they were earrings, though there is much difficulty in determining how they would be fastened to the ear (TBM III. p.81). Others have concluded that they were worn individually as part of a bead necklace. |*|

“Scarabs continue to be used as amulets and perhaps signet items. Most common types of scarabs are decorated with animals (lion, fish, horse, scorpion), good luck expressions (usually egyptian symbols for life, prosperity or health) and pharaonic names (sometimes even the names of kings of the Eighteenth Dynasty). Scaraboids, scarab-like seals, appear more frequently. |*|

“Bangles with overlapping ends become more common than the open- end forms of the Late Bronze Age. Earlier Iron I-II bangles tend to be more slender and tappered than bangles dated to the end of The Late Iron Age. These later examples are heavy looking. Egyptian or egyptianize amulets common to the early Iron Age continue to be found in The Late Iron Age. By late The Late Iron Age, however, the number and types of amulets decreases dramatically throughout most of the region with the exception of sites on the immediate coast. The toggle pin, the Bronze Age fastener, disappears by the late Iron Age and is replaced by the fibula, or safety pin. This becomes the preferred fastener of the first millennium. Such fasteners, made of bronze or iron, vary in the shape of the bow and added decorations. |*|

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons, Schnorr von Carolsfeld Bible in Bildern, 1860

Text Sources: John R. Abercrombie, University of Pennsylvania, Department of Religious Studies, University of Pennsylvania; James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), Princeton, Boston University, bu.edu/anep/MB.html; “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024