Home | Category: Late Stone Age and Copper and Bronze Age / Canaanites and Early Biblical Peoples / Canaanites and Early Biblical Peoples

CANAANITE LIFE

Anthropoid coffin from Deir al-Balah

According to the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology: Education, work and leisure were concentrated in and around the home. According to the Bible, the ideal family in Ancient Israel was large and patriarchal. The extended family or beit 'av (father's house) consisted of three generations (father, married sons, grandchildren) living together. Excavated houses from the Bronze and Iron Age are small and suggest an average family size of four to eight people. Although extended families might have occupied more than one house, high mortality rates probably kept most families from achieving the biblical ideal. [Source: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology |~|]

“The societies of the Bronze and Iron Age southern Levant were patriarchal and gender was an important factor in shaping the opportunities and social roles of the individual. In art and literature, women were portrayed as mothers and objects of desire, but also as warriors and priestesses. Interpreting evidence for the role of women in ancient society is difficult, since the evidence itself may be a product of the interests and priorities of men.

“In Canaan and Ancient Israel, people depended on storing sufficient food, fodder and seed to sustain them from one harvest to the next, and a little beyond. In the Bronze and Iron Age, people in the southern Levant never developed the kind of centralized storage and redistribution systems common in Egypt and Mesopotamia. |~|

“Families dedicated a good amount of time and floor space to storage. Ceramic storage jars or clay bins were used to store foodstuffs or liquids by sealing them to trap in carbon dioxide and thus prevent spoilage. Under the dry environment conditions of the southern Levant, it was necessary to store more than was needed between harvests. With poor harvests coming as frequently as one year in every four, farmers always had to keep a reserve of seed stock on hand. |~|

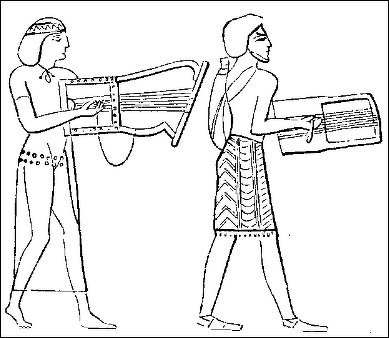

“Fermentation, oil extraction and drying were all ways of converting food into more stable, and hence, storable products. Feeding harvested crops to livestock was a means of "storage on the hoof" — the animals converted the fodder into meat or milk. Men and women typically worked from sunrise to sundown, perhaps taking a siesta in the hottest part of the afternoon. Leisure time would be spent in storytelling, music and dance. Games involving moving pieces across a board according to the roll of dice were popular.|~|

Websites and Resources: Bible and Biblical History: ; Biblical Archaeology Society biblicalarchaeology.org ; Bible History Online bible-history.com Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks ; Jewish History Websites: Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ;

RELATED ARTICLES:

CANAANITES: WHO THEY WERE, THEIR CITIES AND DEPICTIONS OF THEM IN THE BIBLE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITES: HISTORY, ORIGINS, INVASIONS, BATTLES factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITE LANGUAGE AND THE WORLD'S OLDEST ALPHABETIC WRITING africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITE RELIGION: TEMPLES, OFFERINGS, RITUALS AND CULTS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITE GODS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITE HOUSES, BUILDINGS AND SETTLEMENTS factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITE FOOD, DRINK, DRUGS, CLOTHES, JEWELRY africame.factsanddetails.com ;

CANAANITE ART, CRAFTS, MUSIC AND GAMES africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Dawn of Israel: A History of Canaan in the Second Millennium BCE”

by Lester L. Grabbe Amazon.com ;

“The Canaanites: Their History and Culture from Texts and Artifacts” by Mary Ellen Buck

Amazon.com ;

“Israelite Religions: An Archaeological and Biblical Survey”

by Richard S. Hess Amazon.com ;

“Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan” by John Day , Andrew Mein, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Stories from Ancient Canaan” by Michael D. Coogan and Mark S. Smith Amazon.com ;

“Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity: An Archaeological Study of Egyptians, Canaanites, Philistines, and Early Israel, 1300-1100 B.C.E.” by Ann E Killebrew Amazon.com ;

“Hazor: Canaanite Metropolis:Israelite City” by Amnon Ben-Tor Amazon.com ;

“The Bible Unearthed” by I. Finkelstein and N. Asher Silberman Amazon.com ;

“Archaeology of the Bible: The Greatest Discoveries From Genesis to the Roman Era”

by Jean-Pierre Isbouts Amazon.com ;

“Unearthing the Bible: 101 Archaeological Discoveries That Bring the Bible to Life” Amazon.com ;

“Zondervan Handbook of Biblical Archaeology: A Book by Book Guide to Archaeological Discoveries Related to the Bible” by J. Randall Price and H. Wayne House Amazon.com ;

“NIV, Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible (Context Changes Everything) by Zondervan, Craig S. Keener Amazon.com ;

“Egypt, Canaan and Israel in Ancient Times” by Donald Redford Amazon.com ;

Tale of Sinuhe: Insights into Daily Life in the Middle Bronze Age

Scarab with a walking lion

Description of Asiatic life from the Tale of Sinuhe (Middle Bronze Age, 2200 - 1570 B.C.): “He set me at the head of his children. He married me to his eldest daughter. He let me choose for myself of his country, (80) of the choicest of that which was with him on his frontier with another country. It was a good land, named Yaa. Figs were in it, and grapes. It had more wine than water. Plentiful was its honey, abundant its olives. Every (kind of) fruit was on its trees. Barley were there, and emmer. There was no limit to any (kind of) cattle. (85) Moreover, great was that which accrued to me as a result of the love of me. He made me ruler of a tribe of the choicest of his country. Bread was made for me as daily fare, wine as daily provision, cooked meat and roast fowl, beside the wild beasts of the desert, for they hunted (go) for me and laid before me, beside the catch of my (own) hounds. Many . . . were made for me, and milk in every (kind of) cooking. [Source: James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), 18-19, Princeton, 1969, web.archive.org]

“I spent many years, and my children grew up to be strong men, each man as the restrainer of his (own) tribe. The messenger who went north or who went south to the Residence City (95) stopped over with me, (for) I used to make everybody stop over. I gave water to the thirstv. I put him who had strayed (back) on the road. I rescued him who had been robbed. When the Asiatics became so bold as to oppose the rulers of foreign countries,l3 I counseled their movements. This ruler of (100) (Re)tenu had me spend many years as commander of his army. Every foreign country against which I went forth, when I had made my attack on it, was driven away from its pasturage and its wells. I plundered its cattle, carried off its inhabitants, took away their food, and slew people in it (105) by my strong arm, by my bow, by my movements, and by my successful plans. I found favol in his heart, he loved me, he recognized my valor, and he placed me at the head of his children, when he saw how my arms fiourished.

“A mighty man of Retenu came, that he might challenge me (110) in my (own) camp. He was a hero without his peer, and he had repelled all of it.l7 He said that he would fight me, he intended to despoil me, and he planned to plunder my cattle, on the advice of his tribe. That prince discussed (it) with me, and I said: "I do not know him. Certainly I am no confederate of his, (115) SO that I might move freely in his encampment. Is it the case that I have (ever) opened his door or overthrown his fences? (Rather), it is hostility because he sees me carrying out thy commissions. I am reallv like a stray bull in the midst of another herd, and a bull of (these) cattle attacks him....

“During the night I strung my bow and shot my arrows, I gave free play to my dagger, and polished my weapons. When day broke, (Re)tenu was come. (I30) It had whipped up its tribes and collected the countries of a (good) half of it. It had thought (only) of this fight. Then he came to me as I was waiting, (for) I had placed myself near him. Every heart burned for me; women and men groaned. Every heart was sick for me. They said: "Is there another strong man who could fight against him?" Then (he took) his shield, his battle-axe, (I35) and his armful of javelins. Now after I had let his weapons issue forth, I made his arrows pass by me uselessly, one close to another. He charge me, and I shot him, my arrow sticking in his neck. H cried out and fell on his nose. (140) I felled him with his (own) battle-axe and raised my cry of victory over hi back, while every Asiatic roared. I gave praise to Montu, while his adherents were mourning for him. This rule Ammi- enshi took me into his embrace. Then I carried off his goods and plundered his cattle. What he had planned to do (145) to me I did to him. I took wha was in his tent and stripped his encampment. I became great thereby, I became extensive in my wealth, I became abundant in my cattle.”

Canaanite Houses and Settlements

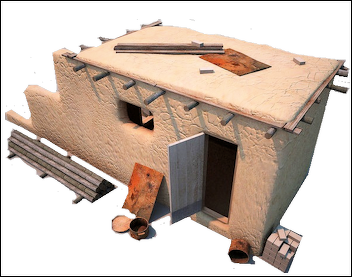

Typical types of dwelling in the Iron Age were the "four-room" house and the "three-room" house. The latter is divided into three parts, each with a distinct function, and contains: 1) a central activity area; 2) a stable area; 3) a storage room; 4) sleeping quarters; and 5) clay roof. According to the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology: “A doorway entered into a white-plastered area (1), which served as a space for food processing and other household tasks. In larger houses, this area may have been a courtyard surrounded by rooms and open to the sky above. A row of pillars divided this room from a cobblestone paved area (2) to the side of the house. This space was used for stabling animals and for the storage of agricultural produce. The long broad room at the back of the house (3) was used for long-term storage. Space for sleeping and entertaining guests probably was located on the second floor (4). The second floor may have been reached by a flight of stairs or wooden ladders. The walls of the houses were built of roughly-hewn blocks of stone and the roof (5) consisted of wooden beams covered with layers of branches and smoothed down clay. This style of house is extremely common throughout the Iron Age, especially in the territory of Israel and Judah. Numerous finds from along the Mediterranean coast of Israel and in the highlands of Jordan make it clear, however, that this house type also was used in Ammon, Moab, Edom and Philistia. [Source: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology |~|]

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “The Hebrews were established in Canaan. Their status in the eyes of the Canaanites, how they organized their communities, what patterns of living they developed, and how they worshipped is not known. Some may have lived in tents (Judg. 4:17; 5:24) or caves (Judg. 6:2); others adopted the cultural patterns of settled society. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org]

“On the basis of archaeological study, it is surmised that three kinds of Hebrew settlements were developed.12 Villages were built on abandoned tells or in previously unoccupied areas. Where Canaanite cities had been destroyed, new dwellings were constructed amid the ruins. In some instances, by mutual agreement, Hebrews settled more or less peacefully among the Canaanites (Josh. 9:3-7). By comparison with Canaanite dwellings, Hebrew houses were poorly built. In new villages little attention was given to town planning and homes were constructed wherever the owner desired.

Defensive walls were relatively weak and crudely composed, revealing limited mastery of structural engineering principles. Hebrew pottery, in contrast to well levigated, well fired Canaanite ware, appears quite poorly made. Some Hebrews ventured into Canaanite agricultural and commercial pursuits, others continued to raise flocks and herds (I Sam. 17:15, 34; 25:2). Despite efforts of a conservative element, fiercely loyal to old tribal ways, Canaanite cultural patterns were gradually assimilated. The unsettled nature of the times is revealed by the numerous destroyed layers from the thirteenth to eleventh centuries found in some excavations.”

See Separate Article: CANAANITE HOUSES, BUILDINGS AND SETTLEMENTS: africame.factsanddetails.com

Tools and Furniture in the Canaanite Era

Abercrombie wrote: “Plough points, lithic sickles and other agricultural tools occur in domestic areas on tells. Grinding stones and bowls are common implements uncovered mostly but not exclusively in domestic areas on tells. (Note: grinding stones did occur in the Temple VII and suggest preparation of ritual meals perhaps.) There is little variations in style of such stones from third millennium to the common era. The chalice, found in the Temple of VII, is dated to just the Late Bronze and early Iron Age. [Sources: John R. Abercrombie, University of Pennsylvania, Department of Religious Studies, University of Pennsylvania; James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), Princeton, Boston University, bu.edu/anep/MB.html |*|]

“Polished limestone or diorite dome-shaped weights occur from time to time at seventh-sixth century levels. Use of such weights is well attested in the Bible (Gen. 23:16, Deut. 25:13-15). Although most weights are unscribed, a number do have measure values written on them. Usually the stone is inscribed with the hieratic symbol for weight followed by the actual shekel weight in Phoenician script. The earlier whorls tend to be conical in shape. Towards the end of the late Iron Age period, whorls become more round. |*|

“Numerous examples of wooden boxes with bone inlay do occur at arid sites like Jericho (Tell es-Sultan) or the delta region of Egypt. In addition to the wooden boxes, wood bowls with rams and lion (?) heads on the bowl's rim are common and sometimes duplicated in clay as is the case from Gibeon (el Jib). Wooden combs, when preserved, occur in the wooden cosmetic boxes or in reed baskets. At Jericho, Kenyon uncovered fine collection of wooden tables and stools. |*|

“The stone throne from Beth Shan Temple VII, other examples from Hazor,and also the depiction of a throne on the Megiddo ivory or the Ahiram sarcophagus form a useful corpus for describing chairs of royalty and perhaps deities. The Beth Shan throne, like the one etched on one of the Megiddo ivories, has griffins, or cherubs, depicted on its sides. On the back of the throne is a tree and the depictions together reminds one of the typical motifs of animals surrounding the tree of life that occur on cylinder seals and some pottery pieces. The common phrase when referring to Yahweh as king in association with the ark, he who sits/enthrone on cherubs (add passages here), might have been visualized by the ancient Israelites in these terms. |*|

Glass, Alabaster and Stone Vessels from the Canaanite Era

used for feeding or water trough from Megiddo

John R.Abercrombie of the University of Pennsylvania wrote: “Egyptian and egyptianized alabaster vases become common particularly in burials. Forms such as the juglet, baggy-shaped vessels, small jars and ovoid flasks may have contained ointments used in the funerary rites or offerings for the next world. Generally one distinguishes between Egypt imports and locally-made vessels by the color and manufacture of a piece. Egyptian pieces are usually translucent in color and are carved with a drill that leaves horizontal lines on the stone. Locally-made vases are white in color and are carved by a chisel that produces vertical marks on the vase. Faience vessels first appear towards the end of the Middle Bronze Age. Generally two forms dominate in this period: a bottle with rosette design and a juglet with leaf design. [Sources: John R. Abercrombie, University of Pennsylvania, James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), Princeton, Boston University, bu.edu/anep/MB.html |*|

“Egyptian and egyptianize stone vessels become common in the Late Bronze Age (1570 - 1200 B.C.) particularly as the local industry develops at sites like Beth Shan. Forms in the early Late Bronze reflect the imported bag-shaped vessels of the Middle Bronze period. By Late Bronze Age , the pyxis and tazza become the dominant pieces. The tazza, the most identifiable form of this period, is an exquisite vessel that is usually represented in tribute by Asiatics. Earliest examples of the tazza have two pieces, a foot and bowl. The two-ribbed tazza dates earlier than the three- ribbed example as Flinders Petrie first noted. The last forms of tazza are one piece unlike the earlier foot and bowl example.

“Other shapes from the end of the Bronze Age include bowls, imitation of imported Aegean forms, lentoid flask (LB tomb at Beth Shemesh, Fosse Temple III Lachish) or amphoriskos, and small ceramic forms including goblets (Deir el-Balah Tombs 114, 118) or juglets. Although most known examples from Palestine of the swimming girl cosmetic spoon are carved in ivory (Megiddo St. VIIA, Beth Shan Tomb 90, Tell es-Sa'idiyeh Tomb 101), a fine alabastron example was discovered in Tomb 118 at Deir el-Balah. |*|

“Imported faience vessels appear in some of the richest burials and in large palaces and temples. The delicate pieces often mimic imported Aegean vessels: the lentoid flask, pyxis, Syrian flask, amphoriskoi. Other forms, kohl pots and bowls with floral pattern and handles shaped in the head of a female, are common egyptian forms. |*|

Little change is noted between alabaster vessels of the end of the Late Bronze and the early Iron Age periods. The dominate forms, the pyxis and tazza, are characteristics shapes although other Late Bronze Age (1570 - 1200 B.C.) shapes can also be cited including pyxis, kohl pots, and lentoid flask. In the late Iron Age the number of examples of alabaster pieces decreases. Fewer vessels appear to be imports, and most locally manufactured vessels are pyxis, goblets or one-handled cups. Early Iron Age faience vessels vary little from forms of the Late Bronze Age . By the late Iron Age the types of faience shapes decreases dramatically with the disappearance of most egyptian shapes. The most common type of faience vessel in this period in the small cup or chalice. |*|

Canaanite Incense Burners and Bronze Objects

Abercrombie wrote: “Incense burners from Beth Shan are tall, slender structures with specialized iconography: birds or people at windows, snakes crawling up the sides, and animals. Although most of the Beth Shan examples date to early Iron Age , fragments of a large incense burner from this sites as well as parallels at other sites (e.g. Hazor) show that this form appears in the thirteenth century B.C. as well. A different type of incense burner, a lamp with pedestal, is found in Bronze Age level and may be depicted in the hands of an Asiatic on the walls of the Temple of Medinet Habu. [Sources: John R. Abercrombie, University of Pennsylvania, James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), Princeton, Boston University, bu.edu/anep/MB.html |*|]

Scarab with a walking lion

A fine collection of incense burners from Beth Shan are tall, slender structures with specialized iconography: birds or people at windows, snakes crawling up the sides, and animals. Most parallels date to Late Bronze Age (1570 - 1200 B.C.) and the early Iron Age (see Tell Qasile), though a few burners with floral patterns, birds, monsters and female nudes (e.g. Tanaach) may be placed in the tenth century. || “At Pella, an altar or incense burner dates to The Late Iron Age. The large rectangular clay structure had figurine heads normally where horns would be located on a horn altar. The front is decorated with nude figures at the corner. Evidence of burning on the top leads many archaeologists to identify the artifact as an incense altar. Special pedestal cups with holes just below the rim are thought to be incense burners. Such cups are common in tombs and domestic sites in the Transjordan region. ||

“Bronze bowls, jars and sometimes even strainers appear in the richer primary burials: Deir el-Balah Tomb 114, northern cemetery at Beth Shan, Governor's tomb at Tell el-Ajjul, Tell el-Farah (S), Baq'ah Valley B3. James B. Pritchard in his study of a fine collection from Tell es-Sa'idiyeh concluded that pieces are parts of wine sets. This conclusion fits well with some other artifacts, large Canaanite storage jar used in viticulture, as well as references to Canaanite burial offerings of wine and bread. Bronze mirrors are occasionally found in some of the richest tombs: Deir el-Balah Tombs 114, 118, Tell el-Ajjul, Beth Shan Tomb 90?, Tell es-Sa'idiyeh ??. A exquisite bronze mirror with a bronze handle in the scpae of a woman comes from Acco. The considerable presence of bronze objects at Beth Shan, Tell es- Sa'idiyeh (possibly ancient Zarethan) and also the nearby site of Deir Alla (ancient Succoth) may be referenced in 1 Kings 7:46, a passage that mentions the smelting of bronze vessels in this region. |*|

Canaanite Pottery from the Bronze Age

John R. Abercrombie of the University of Pennsylvania wrote: Early Middle Bronze Age pottery continues the flat-base tradition of the Early Bronze Age. Some vessels, particularly north of Shechem, have the wavy ledge handles characteristic of the Early Bronze (example of Early Bronze Jar with handle). Four-spouted lamps with round or flat bases are perhaps the most identifiable form. The single-spouted lamp, the characteristic form of the Bronze Age onward, appears at the end of the early Middle Bronze Age and continues into the Roman period changing and improving over the centuries in logical and functional ways. Characteristic pieces include teapots, goblets and small amphoriskoi. [Sources: John R. Abercrombie, University of Pennsylvania, James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), Princeton, Boston University, bu.edu/anep/MB.html |*|]

“Little treatment (that is, slips, etched designs or paint) is applied to most vessels. On an occasional vessel there may occur horizontal bands of incision or single or double line of punches just below the base of the rim. A few vessels may have one to two knobs applied to the shoulder. In the northern group, vessels may have incised designs as well as raised rope- like patterns around the shoulders. A few vessels are coated with a dull, unburnished red slip. |*|

Late Bronze period pottery

“There is regional variation in pottery style. A cup-like vessel, commonly called a toothbrush holder, is a common form among the southern group (Gibeon [el Jib]). Large globular vessels with wavy handles are identifiable forms of the northern group (Beth Shan). The northern group also seems to have a wider variety of ceramic forms than tombs belonging to the southern group (Gibeon [El Jib]). |*| Interesting Middle Bronze Age pieces include the “Four-spouted lamp (62-30-341, Gibeon [el Jib]); Jar with loop handles (34-20-635, Beth Shan); spouted Jug (34-20-365, Beth Shan); Round, globular Jar (Gibeon [el Jib]); the "British toothbrush holder" [sic] (62-30-263, Gibeon [el Jib] Tomb 57); and Round, globular Jar with vestigal handles (Gibeon [el Jib]). The first four pieces are on display at the University Pennsylvania Museum).

“Painted pottery and imports vessels are the characteristics of the Late Bronze ceramic repertoire. Painted pottery first appears at the very end of the late Middle Bronze Age (Bichrome ware) and continues to be the preferred treatment on vessels throughout the period. In fact, the amount of applied paint seems to increase as one moves from the beginning the early Late Bronze to the end of Late Bronze Age . The use of applied paint to decorate vessels decreases by the latter half of Iron I. |*|

“Middle Bronze forms continue into the Late Bronze Age, but do change in shape slowly. The heavy carination on bowls and chalices changes in favor of softer, rounder lines. Other characteristic shapes (e.g. barrel juglets) disappear by Late Bronze Age . New forms enter the repertoire, in particular imitations of imported vessels. Imports from Syria and the Aegean world are together a definable trait of the Late Bronze Age (1570 - 1200 B.C.) ceramics. Cypriote bilbils and Syrian flasks become common by the end of the early Late Bronze and are imitated by Late Bronze Age . Mycenean imports (pyxides, stirrup jars and amphoriskoi) become common place by the late Late Bronze Age and are imitated by local potters from that point on. The presence of such imports, along with other evidence (e.g. Canaanite storage jar and several shipwrecks off the southern coast of Turkey), indicate evidence of trade with the greater Aegean world. It appears that commodities such as scented and blended wines and various grades of oils were exported from the Levant. The nature of imported goods in Aegean vessels is still open to some discussion, and some scholars have speculated that diluted opium was imported particularly in bibils. In addition to locally made vessels and Aegean imports, one finds Egyptian forms especially at the very end of the Bronze Age. |*|

Interesting pieces from the Late Bronze Age include Open-spouted lamp (Beth Shan Tomb 42); Small Barrel Juglets (Beth Shan Tomb 42); Shoulder-handle Jugs (Beth Shan Tomb 42); Bilbil, BR I (Gibeon Tomb 10); Syrian Flask (Upper Egyptian Gallery, Univ. of Penn. Museum; Degenerated carinated Bowl (Gibeon Tomb 10); Decorated round bowl (Gibeon Tomb 10); Single handled Jug (Gibeon Tomb 10); Imitation of Bilbil (Gibeon Tomb 10); Small pilgrim flask (Beth Shan Tomb 241); Stirrup Jar (Beth Shan Tomb 90); Lentoid Flask (Beth Shan Tomb 90); and “Unusual Funerary "Beer" Jar with hole at base (Tell es- Sa'idiyeh Tomb 104).

Iron Age (1200 - 550 B.C.) Pottery in Canaan and Ancient Israel

Abercrombie wrote: In the early Iron Age “There is little change in the shapes and style of pottery from Late Bronze Age . An excessive use of paint on the shoulder and upper half of vessels is found on early the early Iron Age vessels, but by late the early Iron Age it begins to disappear. Shapes of Bronze Age vessels continue into the Iron I, yet gradually the pots become less slender and more globular in shape in The Late Iron Age. Most characteristic forms, such as the dipper juglet, jars and storage vessels, continue throughout the Iron Age; imports (pyxis or pilgrim flask), however, begin to disappear or decrease in number by The Late Iron Age. [Sources: John R. Abercrombie, University of Pennsylvania, James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), Princeton, Boston University, bu.edu/anep/MB.html |*|]

Interesting pieces include: “Single-handled jug with painted decoration (Beth Shemesh Stratum III); Small, single-handled juglet with handle in the middle of the neck and pyxis (Beth Shemesh Stratum III); Pyxis with line design (Beth Shemesh Stratum III); Pyxis with line design (Gibeon Tomb 3); Hand-burnished? bowl (Gibeon Tomb 3); Single spouted lamp (Gibeon Tomb 3) |*|

“The appearance of Philistine style pottery (Mycenean IIIC1b) assists in dating late twelfth and eleventh century material. The decorative style with its swirls, birds, metopes and checkerboard patterns reflects Aegean pottery traditions and is intrusive into this area of the Levant. Some pottery forms (e.g. bell-shaped kraters and horn-shaped pyxis) may also be considered intrusive, although the vast majority of forms with such decor are part of the local potter's tradition by this time. |*|

Interesting pieces from this period include:“Small bell-shaped bowl with spiral designs, L-20-124 on display (Beth Shemesh Stratum III); Large bell-shaped krater with spiral design, 33-4-103 on display (Beth Shemesh Stratum III); Fragment of large bell-shaped krater with spiral design (Beth Shemesh Stratum III); Philistine Pottery, on display (Beth Shemesh Stratum III) Beer Jar with spiral designs, metopes and vertical lines, 33-5-46 on display (Beth Shemesh Stratum III); Horn-shaped (?) pyxis with red line design (Beth Shemesh Stratum III); Elongated pyxis with no decoration (Beth Shemesh Stratum III); “Sherd with circular spiral and line design (Beth Shemesh Stratum III); Sherd with bird and checkerboard pattern, L-20-110 on display (Beth Shemesh Stratum III); Sherd with bird and line design (Beth Shemesh Stratum III); Sherd with maltese cross (Beth Shemesh Stratum III).

“The Late Iron Age:By The Late Iron Age, painted treatment on most vessels has been replaced first by hand-burnishing and later by wheel-burnishing. Small black juglets are particularly good examples for the type of treatment on pottery forms. The earliest examples from the twelfth century receive little to no treatment and are crude looking pieces with a handle in the middle of the neck. By early The Late Iron Age, the juglet begins to be burnished slightly, but lacks the luster of the later small palm-sized, black juglets of The Late Iron Age. The handles also move further up the neck towards the rim by late The Late Iron Age. |*|

“The delicate lines and shapes of the Late Bronze and the late Iron Age give way to a more globular and heavy look characteristic of late the late Iron Age pottery. In short, if it is fat and globular with wheel burnishing, it probably dates more towards the end of the late Iron Age than the beginning. |*|

Interesting pieces from this period include:“Round, deep bowl with burnishing (Sa'idiyeh V) Samaria bowl with thick walls and wheel burnishing of deep red slip (Beth Shan IV); “Black-on-Red juglet (Beth Shan); Phoenician Red-slip juglet (Beth Shan); Black juglet (Sa'idiyeh V); Dipper Juglets (Beth Shan and Sa'idiyeh V; Cooking Pot (Beth Shemesh Stratum II); Single-spouted lamp (Sa'idiyeh V).

Collection of Bronze Age and Iron Age pottery from Canaan and ancient Israel can be found at the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, Beth Shemesh and the University of Pennsylvania Museum.

3,600-Year-Old Silver Money from Gaza and Israel?

The 3,600-year-old hacksilver hoard from Tell el-ʿAjjul in Gaza and similar hoards from elsewhere in Palestine and Israel are among the earliest known examples of silver used as currency by weight in Palestine and Israel. These silver hoards contain irregularly cut pieces of the precious metal rather coins but, they were presumably used in a similar fashion. The hoards or silver likely came from the relatively faraway regions of what is now Turkey and Europe, 2023 study suggests. Live Science reported: These newly analyzed hoards date to about 1550 B.C., hundreds of years earlier than other discoveries of silver currency in what is now Israel and Gaza, the researchers said. However, not everyone agrees that this is a new finding, with some experts noting that other research has already found that silver currency was being used during the Middle Bronze Age in this region. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, January 23, 2023]

“The practice of using cut silver as currency may be a sign that administrators in the region — part of the "southern Levant" — were more numerically literate than their predecessors, which enabled them to accurately measure the weight of silver when making payments. "We know that the Middle Bronze Age is a period of [making] large ramparts and fortifications," Tzilla Eshel, an archaeologist at the University of Haifa, told Live Science. "But how do you pay your workers?"

It's possible that workers would have been paid an agreed-upon weight of silver, following the practice already in use in the northern Levant, a region now covered by Lebanon and Syria, Eshel and her colleagues reported in the new study, published in the January issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science. The practice of exchanging silver by weight for other objects of value was also common during the Viking Age in Europe, where silver for this purpose came to be known as "hacksilver" (or "hacksilber"). "The use of silver as currency [in the southern Levant] came in this period because it was needed," Eshel said, "[and] there was a big enough organization that could manage it."

Eshel and her colleagues studied 28 pieces of silver from four hoards found at Bronze Age archaeological sites: one from Gezer in the Judaean Mountains, one from a tomb at Megiddo in northern Israel, one from Shiloh in the West Bank, and one from Tell el-ʿAjjul in Gaza. The authors reported that the silver hoards from Gezer, Shiloh and Tell el-ʿAjjul were not found alongside silversmith tools — a fact that they interpreted as evidence that the hoards were being used only for exchange, and not to create other silver objects. That indicated that weights of silver had been used as a currency in the region since at least the approximate date of those hoards, which span from 1600 B.C. to 1550 B.C., Eshel said. "There would have been different means of exchange, which is always true," she said. But "silver was the means of reference … so if you wanted to value your wheat, or to value your textiles, you would have valued them in silver shekels." A shekel was an ancient measurement of weight, in use since Mesopotamian times, that was equal to just over a third of an ounce, or about 9.6 grams.

Eshel and her colleagues also attempted to determine the origins of the silver in the hoards by studying their chemical impurities and isotopes — variations in the number of neutrons in the nuclei of particular elements, which change over time at known rates due to radiation. The analysis revealed signs of a widespread transition between sources in about 1200 B.C., possibly from silver mined in Anatolia — now Turkey — to silver mined in southeastern Europe, which was then brought to the Levant by long-distance trade. The silver of later origin was surprisingly similar to silver found in famous graves from the Bronze Age Mycenaean culture in Greece; these burials might have the same silver source as the hoard from Tell el-ʿAjjul, the researchers said. "As the silver items from Tell el-ʿAjjul are isotopically similar to silver from the [Mycenaean] Shaft Graves, it is possible that both contemporaneous assemblages originated from the same source," the authors wrote in their study.

Raz Kletter, an archaeologist at the University of Helsinki who has studied ancient economies and silver hoards from the Levant but was not involved in the new research, told Live Science in that the new study "advances our knowledge." However, he said scholars had pointed out 20 years ago that silver must have been used for weight economy since the late Middle Bronze period in the southern Levant, based on studies of the same hoards. Kletter is also concerned that hoards found without metalworking tools were interpreted in the study as being only for exchange. "We cannot identify the owners," he said, "and the places where hoards are hidden ... do not necessarily tell us about their origins."

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons, Schnorr von Carolsfeld Bible in Bildern, 1860

Text Sources: John R. Abercrombie, University of Pennsylvania, Department of Religious Studies, University of Pennsylvania; James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), Princeton, Boston University, bu.edu/anep/MB.html; “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024