JOBS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

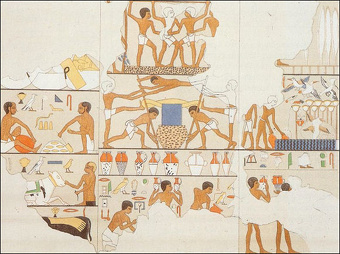

Among those that worked in trades and professions in ancient Egyptian were: barbers, potters, arrow makers, merchants, basket makers, record keepers, tool and weapons makers, goldsmiths, silversmiths, butchers, stonemasons, water carriers, fishermen, estate workers, farmers, tanners, weavers, boatbuilders, furniture makers, bakers, metal workers, pottery makers, beer brewers, bread makers, leatherworkers, spinners, weavers, clothes makers and jewelers.

Artisans were sometimes bondslaves, such as the “metalworker Paicharu of the western town, bondservant of the house of Ramses III in the temple of Amun, subject to the first prophet of Amun-Ra," ' or the “artist SetNakht “of the same temple, "subject to the second prophet of Amun-Ra. " The artisans, however, were not generally reckoned in the department of the companies of workmen like workers in work gangs. Serfs did jobs like carrying water, catching fish, cutring wood, fetching fodder, and similar work. ' [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Many craftsmen and artisans were employed by the state and nobles. Their shops and workshops were often set up near the palaces of the pharaohs, aristocrats or high officials. Their crafts tended to be passed on from one generation to the next. Juan Carlos Moreno García wrote: Specialized workers and artisans, usually working for the king, also put their skills at the service of customers eager to afford high quality equipment for themselves — the sort of private, non-institutional demand so badly documented in administrative papyri. Specialized, large-scale workshops aiming to supply the army, temples, and the palace coexisted with a more modest but widespread artisan production, in the hands of craftsmen (potters, leather workers, weavers, brick makers, etc. ) who were often the object of mockery in the satire-of-trades texts. Finally, the supplying of cities with charcoal, fresh vegetables, meat, and fish is occasionally referred to in administrative documents and private letters, thus giving an idea of the impact of urban markets on the economic activities, trades, and lifestyles of people living far away from cities. That fishermen, for instance, were paid in silver and, in turn, paid their taxes in silver during the reign of Ramses II, suggests that markets (and traders) played an important role in the commercialization of fish, harvests, and goods, in the use of precious metals as a means of exchange, and in the circulation of commodities. [Source Juan Carlos Moreno García, University of Paris IV-Sorbonne, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2018; escholarship.org ]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years” by Elizabeth Wayland Barber (1994) Amazon.com;

“The Book of Looms: A History of the Handloom from Ancient Times to the Present” by Eric Broudy (2021) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Scribes: A Cultural Exploration” by Niv Allon and Hana Navratilova | (2017) Amazon.com;

“Weavers, Scribes, and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East” by Amanda H Podany (2022) Amazon.com;

“Economic Life at the Dawn of History in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt: The Birth of Market Economy in the Third and Early Second Millennia BCE” by Refael (Rafi) Benvenisti and Naftali Greenwood (2024) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Beni Hassan: Art and Daily Life in an Egyptian Province” by Naguib Kanawati and Alexandra Woods (2011) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The World of Ancient Egypt: A Daily Life Encyclopedia" by Peter Lacovara, director of the Ancient Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage Fund (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2016) Amazon.com

Satire of the Trades

A text called “The Satire of the Trades” from “ Instruction of Dua-Khety”from the Middle Kingdom (2050- 1710 B.C.) offers a scribe’s unflattering view of various jobs. It goes: “I do not see a stoneworker on an important errand or a goldsmith in a place to which he has been sent, but I have seen a coppersmith at his work at the door of his furnace. His fingers were like the claws of the crocodile, and he stank more than fish excrement. [Adolf Erman, “The literature of the ancient Egyptians; poems, narratives, and manuals of instruction, from the third and second millennia B. C.,” 1927, London, Methuen & co. ltd., pp. 67f. reshafim.org]

“Every carpenter who bears the adze is wearier than a fieldhand. His field is his wood, his hoe is the axe. There is no end to his work, and he must labor excessively in his activity. At nighttime he still must light his lamp. The jeweler pierces stone in stringing beads in all kinds of hard stone. When he has completed the inlaying of the eye-amulets, his strength vanishes and he is tired out. He sits until the arrival of the sun, his knees and his back bent at (the place called) Aku-Re. The barber shaves until the end of the evening. But he must be up early, crying out, his bowl upon his arm. He takes himself from street to street to seek out someone to shave. He wears out his arms to fill his belly, like bees who eat (only) according to their work.

“The reed-cutter goes downstream to the Delta to fetch himself arrows. He must work excessively in his activity. When the gnats sting him and the sand fleas bite him as well, then he is judged. The potter is covered with earth, although his lifetime is still among the living. He burrows in the field more than swine to bake his cooking vessels. His clothes being stiff with mud, his head cloth consists only of rags, so that the air which comes forth from his burning furnace enters his nose. He operates a pestle with his feet with which he himself is pounded, penetrating the courtyard of every house and driving earth into every open place.

“I shall also describe to you the bricklayer. His kidneys are painful. When he must be outside in the wind, he lays bricks without a garment. His belt is a cord for his back, a string for his buttocks. His strength has vanished through fatigue and stiffness, kneading all his excrement. He eats bread with his fingers, although he washes himself but once a day.

“It is miserable for the carpenter when he planes the roof-beam. It is the roof of a chamber 10 by 6 cubits. A month goes by in laying the beams and spreading the matting. All the work is accomplished. But as for the food which is to be given to his household (while he is away), there is no one who provides for his children.”

More Jobs from “Satire of the Trades”

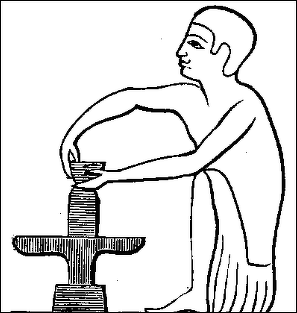

pottery maker

“The Satire of the Trades” from “ Instruction of Dua-Khety” from the Middle Kingdom (2050- 1710 B.C.) continues: “The vintner carries his shoulder-yoke. Each of his shoulders is burdened with age. A swelling is on his neck, and it festers. He spends the morning in watering leeks and the evening with corianders, after he has spent the midday in the palm grove. So it happens that he sinks down (at last) and dies through his deliveries, more than one of any other profession.

“The fieldhand cries out more than the guinea fowl. His voice is louder than the raven's. His fingers have become ulcerous with an excess of stench. When he is taken away to be enrolled in Delta labour, he is in tatters. He suffers when he proceeds to the island, and sickness is his payment. The forced labour then is tripled. If he comes back from the marshes there, he reaches his house worn out, for the forced labor has ruined him.

“The weaver inside the weaving house is more wretched than a woman. His knees are drawn up against his belly. He cannot breathe the air. If he wastes a single day without weaving, he is beaten with 50 whip lashes. He has to give food to the doorkeeper to allow him to come out to the daylight. The arrow maker, completely wretched, goes into the desert. Greater than his own pay is what he has to spend for his she-ass for its work afterwards. Great is also what he has to give to the fieldhand to set him on the right road to the flint source. When he reaches his house in the evening, the journey has ruined him.

“The courier goes abroad after handing over his property to his children, being fearful of the lions and the Asiatics. He only knows himself when he is back in Egypt. But his household by then is only a tent. There is no happy homecoming. The furnace-tender, his fingers are foul, the smell thereof is as corpses. His eyes are inflamed because of the heaviness of smoke. He cannot get rid of his dirt, although he spends the day at the reed pond. Clothes are an abomination to him. The sandal maker is utterly wretched carrying his tubs of oil. His stores are provided with carcasses, and what he bites is hides.

“The washerman launders at the riverbank in the vicinity of the crocodile. I shall go away, father, from the flowing water, said his son and his daughter, to a more satisfactory profession, one more distinguished than any other profession. His food is mixed with filth, and there is no part of him which is clean. He cleans the clothes of a woman in menstruation. He weeps when he spends all day with a beating stick and a stone there. One says to him, dirty laundry, come to me, the brim overflows.

“The fowler is utterly weak while searching out for the denizens of the sky. If the flock passes by above him, then he says: would that I might have nets. But God will not let this come to pass for him, for He is opposed to his activity. I mention for you also the fisherman. He is more miserable than one of any other profession, one who is at his work in a river infested with crocodiles. When the totalling of his account is made for him, then he will lament. One did not tell him that a crocodile was standing there, and fear has now blinded him. When he comes to the flowing water, so he falls as through the might of God.”

Scribe: A Good Job in Ancient Egypt

Being a scribe was considered a good job. Dr. Carol R. Fontaine, an assistant professor of Old Testament at the Andover Newton Theological School in Massachusetts, told the New York Times, that, according to papyri that have been translated, the scribes regarded writing as a good way to make a living, much better than being potterymakers (who were ''smeared with soil, like one whose relations have died''), merchants (who spent all their time in river travel), watchmen (who suffered bad hours), shoemakers (who forever had ''red hands'') and soldiers (who drank bad water, marched up hills a lot and ran the risk of getting killed). See Scribes Under People and Life, Language

Ancient Egypt writing-and also reading-was a professional rather than a general skill. Being a scribe was an honorable profession. Professional scribes prepared a wide range of documents, oversaw administrative matters and performed other essential duties.

The scribes were highly prized by both the pharaoh and the priesthood, so much so that in some of the pharaoh's tombs, the pharaoh himself is depicted as a scribe in pictographs. The scribes were in charge of writing magical texts, issuing royal decrees, keeping and recording the funerary rites (specifically within The Book of The Dead) and keeping records vital to the bureaucracy of Ancient Egypt. The scribes often spent years working on the craft of making hieroglyphics, and deserve mentioning within the priestly caste as it was considered the highest of honors to be a scribe in any Egyptian court or temple. +\ [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

See Separate Article: SCRIBES IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Craftsmen in Ancient Egypt

The low esteem in which uper class Egyptians held their farmers extended also to their craftsmen. According to the learned opinion of the scribes, the latter were also poor creatures who led an inglorious existence, half pitiable and half ridiculous. Thus a poet of the Middle Kingdom speaks, for example, of the metalworker: “I have never seen the smith as an ambassador, Or the goldsmith carry tidings; Yet 1 have seen the smith at his work At the mouth of his furnace, His fingers were hkc crocodile (hide), He stank more than the roe of fish. " The same scribe also thus describes the work of a wood-carver: "Each artist who works with the chisel Tires himself more than he who hoes (a field). The wood is his field, of metal are his tools. In the night — is he free? He works more than his arms are able. In the night — he lights a light." [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Fortunately we are not dependent on these gloomy sources to form our opinion of Egyptian handicrafts, for the work of the metalworkers and woodcarvers which still exists shows that these industries reached a very high standard in Egypt, a comparatively far higher one in point of fact than either learning or literature. The workmen who created those marvels of gold and ivory, of porcelain and wood, the finish of which we admire to this day, cannot have been such wretched creatures as they were considered by the proud learned professors.

In some cases, craftsmen achieved relatively high status. Anne Austin wrote in the Washington Post: “The village of Deir el-Medina was built for the workmen who made the royal tombs during the New Kingdom (1550 to 1070 B.C.). During this period, kings were buried in the Valley of the Kings in a series of rock-cut tombs...The village was built close enough to the royal tomb to ensure that workers could hike there on a weekly basis. These workmen... were highly skilled craftsmen.” They were given a variety of amenities afforded only to those with the craftsmanship and knowledge necessary to work on something as important as the royal tomb. The village was allotted extra support: The Egyptian state paid them monthly wages in the form of grain and provided them with housing and servants to assist with tasks such as washing laundry, grinding grain and porting water. Their families lived with them in the village, and wives and children could also benefit from these provisions from the state.” [Source: Anne Austin, Washington Post, February 17 2015. Anne Austin is a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University ***]

See Separate Article: CRAFTS IN ANCIENT EGYPT: CRAFTSMEN AND ART OBJECTS africame.factsanddetails.com

Potters in Ancient Egypt

In contrast to carpenters, who suffered from shortages of rare materials, potters had a wealth of the raw material at their command. In all parts of Egypt good clay was to be found for ceramic ware. The earthenware prepared by the potter was almost always of the simplest description; the pots, bottles, and bowls were without any glaze or ornamentation of any kind, except a few lines of paint; they made dolls also, and similar rude figures. The beautiful pottery and the artistic terra-cotta figures of Greece were quite unknown to the more ancient Egyptians. '

Paul T. Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: The clay, or mixture of clay and other materials, was shaped either by hand-forming, using the potter’s wheel, or by molding. The finished form is then dried. This is the last point at which the potter could rework the material by simply adding water to it. Once dry, the material is fired either in the open or in a kiln. Firing leads to the fusion of the clay platelets, which renders the material aplastic. It is the sherds of this aplastic material that are most commonly encountered in the archaeological record. [Source: Paul T. Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

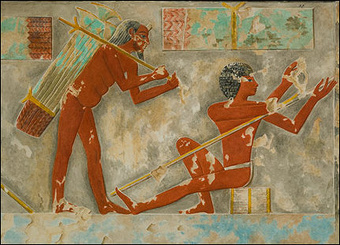

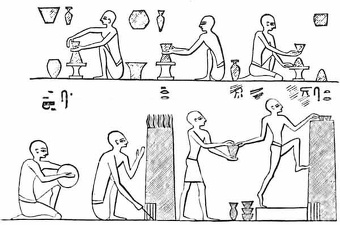

Various pictures of the time of the Old and the Middle Kingdom show us the potter at work. It was only the simplest vessels that were formed entirely by the hand. As a rule the potter's wheel was used, which was turned by the left hand, whilst the right hand shaped the vessel. The pots were then burnt in a stove which seems to have resembled that used by the Egyptian bakers. As is shown in our illustration, the fire was below, and the pots were placed either on the top or inside; in another picture we see the pots standing on the top apparently covered with ashes. '''

An image of potters of the Middle Kingdom in the Beni Hasan tomb shows four men at the potter's wheel: the first one turns it, the second cuts off the pot that is finished, the third one takes it down, the fourth begins a new one. Below is showing the shaping of a plate with the hand, two furnaces, and the carrying away of the pottery that is finished.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN CERAMICS: POTTERS, CLAY, MANUFACTURING, KILNS africame.factsanddetails.com

Weaving in Ancient Egypt

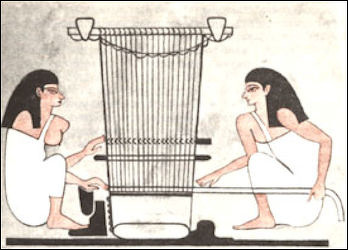

The Egyptians were skilled weavers. Many inscriptions extol the garments of the gods and the bandages for the dead. The preparation of clothes was considered as a rule to be woman's work, for truly the great goddesses Isis and Ncphthys had spun, woven, and bleached clothes for their brother and husband Osiris. During the Old Kingdom this work fell to the household slaves, in later times to the wives of the peasant serfs belonging to the great departments. In both cases it was the house of silver to which the finished work had to be delivered, and a picture of the time of the Old Kingdom shows us the treasury officials packing the linen in low wooden boxes, which are long enough for the pieces not to be folded. Each box contains but one sort of woven material, and is provided below with poles on which it is carried by two masters of the treasury into the house of silver. In other cases we find, as Herodotus wonderingly describes, men working at the loom; and indeed on the funerary stelae of the 20th dynasty at Abydos, we twice meet with men who call themselves weavers and follow this calling as their profession. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

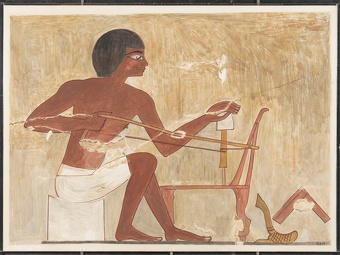

The operation of weaving was a very simple one during the Middle Kingdom. The warp of the texture was stretched horizontally between the two beams, which were fastened to pegs on the floor, so that the weaver had to squat on the ground. Two bars pushed in between the threads of the warp served to keep them apart; the woof-thread was passed through and pressed down firmly by means of a bent piece of wood. " A picture of the time of the New Kingdom however gives an upright loom with a perpendicular frame. The lower beam appears to be fastened, but the upper one hangs only by a loop, in order to facilitate the stretching of the warp. We also see little rods which are used to separate the threads of the warp; one of these [ certainly serves for a shuttle. A larger rod that runs through loops along the side beams of the frame appears to serve to fix the woof-thread, like the reed of our looms.

See Separate Article: WEAVING IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Woodworking in Ancient Egypt

Egyptian carpenters made boats, carriages, portions of houses, furniture, the weapons, coffins, and various kinds of grave goods. When native woods were used, we find a complete lack of planks of any great length; instead objects were made by putting together small planks to form one large one. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Wooden furniture, was generally painted; there were other styles of decoration also in use, appropriate to the character of the material in question. Thin pieces of wood, such as were joined together for light seats or were used for weapons, were left with their bark on; they were also sometimes surrounded with thin strips of barks of other colors — a system of ornamentation which has still a very pleasing effect from the shining dark colors of the various barks. A second method was more artistic; a pattern was cut deeply into the wood and then inlaid with wood of another color, with ivory, or with some colored substance. The Egyptians were especially fond of inlaying “ebony with ivory. " This inlaid work is mentioned as early as the Middle Kingdom, and examples belonging to that period also exist. In smaller objects of brown wood, on the other hand, they filled up the carving with a dark green paste.

The Berlin coffins of the time of the Middle Kingdom are excellent ancient specimens of these various styles of workmanship. Images of coffin making show workman bringing strips of linen for cartonage, polishing and painting the coffins, boring holes in the wooden footboards, sawing planks. They also show a leg of a stool cut with an adze. Behind lies the food for the men, close to which a tired-out workman has seated himself.

See Separate Article: FURNITURE AND WOODWORKING IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Leatherworking in Ancient Egypt

André J. Veldmeijer of the Netherlands Flemish Institute in Cairo wrote: “Leather was used throughout Egypt’s history, although its importance varied. It had many applications, ranging from the functional (footwear and wrist-protectors, for example) to the decorative (such as chariot leather). Although leather items were manufactured using simple technology, leatherworking reached a high level of craftsmanship in the New Kingdom. Among the most important leather-decoration techniques employed in Pharaonic Egypt, and one especially favored for chariot leather, was the use of strips of leather of various colors sewn together in partial overlap. In post-Pharaonic times there was a distinct increase in the variety of leather-decoration techniques. Vegetable tanning was most likely introduced by the Romans; the Egyptians employed other methods of making skin durable, such as oil curing.” [Source: André J. Veldmeijer, Netherlands Flemish Institute Cairo, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“The term “leather” refers to skins that have been tanned or tawed—that is, converted into white leather by mineral tanning, as with alum and salt—rather than cured. In Egypt it appears that skins were not tanned or tawed in the Pharaonic Period; however, thus far we lack detailed, systematic chemical analyses from which to make a conclusive determination. Skins and leather were used throughout Egyptian history, but their importance and quality varied. According to Van Driel- Murray, skins were widely used in the Badarian and Amratian (Naqada I) periods but were largely superseded by cloth in the Gerzean (Naqada II).

ancient Egyptian leatherworkers

“In the Old and Middle kingdoms the use of leather declined in favor of the use of fiber and textiles; skins seem to have been of secondary importance to meat and the production of glue. The Nubian “pan-grave” cultures, however, introduced decorated leather garments, including the loincloth, and containers and pouches of high quality, not dissimilar to those of Predynastic traditions and comparable to leatherwork recovered from other Nubian sites, such as Kerma. During the New Kingdom leather was much more widely used. New weapons technology—such as the introduction of the chariot by Asiatic peoples—was partially responsible for this. Contact with foreign cultures might also have been the reason for the introduction of the leather shoe. It is difficult to say whether the use of leather continued to the same extent into the Third Intermediate Period. The situation in the Late and Ptolemaic periods is as enigmatic. Better attested is leather from the Roman Period, during which the use of vegetable-tanned leather became widespread and in which innovations in technology are apparent.

“In Egypt leather was most commonly made from the skins of cow, sheep, goat, and gazelle, although those of more exotic species such as lion, panther, cheetah, antelope, leopard, camel, hippopotamus, crocodile, and possibly elephant have been identified. Leather was used in a wide variety of items, ranging from clothing, footwear, and cordage, to furniture and (parts of) musical instruments.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN SHOES, HATS AND LEATHERWORKING africame.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Egyptian Beer-Making

According to ancientegyptonline.co.uk: “According to legend, Osiris taught ancient Egyptians the art of brewing beer, but the brewing of beer was traditionally but not exclusively a female activity though which women could earn a little extra money (or bartered goods) for themselves and their families. The main ingredient in the beer was bread made from a rich yeasty dough possibly including malt. The bread was lightly baked and crumbled into small pieces before being strained through a sieve with water. Flavour was added in the form of dates and the mixture was fermented in a large vat and then stored in large jars. However, there is also evidence that beer was brewed from barley and emmer which was heated and mixed with yeast and uncooked malt before being fermented to produce beer. [Source: ancientegyptonline.co.uk ]

Scholars have not been sure how the Egyptians brewed their beer. In some temple art, it appeared that beer was made by crumbling bread into water and letting it ferment by yeast from the bread, yielding a coarse liquid swimming with chaff. But a researcher at Cambridge University in England has now examined beer residues and desiccated bread loaves from Egyptian tombs and found evidence of much more sophisticated brewing techniques in the second millennium B.C.

Dena Connors-Millard of Minnesota State University, Mankato wrote: “Legend teaches that Osiris taught humans to brew beer. In keeping with this idea the Egyptians often used beer in religious ceremonies and as the meal-time beverage. Because of the prevalence of beer in the Egyptian life, many Egyptologists have studied beer residue from Egyptian vessels. For a very long time it was thought that the Egyptians made a crude beer by crumbling lightly baked, well-leavened bread into water. They then strained it out with a sieve into a vat and the water was allowed to ferment because of the yeast from the bread. " [Source: Dena Connors-Millard ,Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com, Menon, Shanti "King Tut's Tipple" Discover, January 1997, Samuel, Delwen "Investigation of Ancient Egyptian Baking and Brewing Methods by Correlative Microscopy" Science July 1996]

See Separate Article: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN BEER: MAKING IT, BREWERIES, PARTIES africame.factsanddetails.com

Making Bread in Ancient Egypt

A bakery found near the Pyramids of Giza was 17 feet long and eight feet wide. The bread was often made in molds or pottery bread pots that produced loaves in many shapes and sizes — round, flat, conical and pointed. Most bread appears to have been made on flat trays, or in bell-shaped pots (14 inches in diameter and 14 inches deep). Archaeologists also found egg-carton-like trenches. The holes held bread-baking pots and the trenches held coals that were used to bake the bread. [Source: David Roberts, National Geographic, January 1995]

The most common type of bread was made by first pouring thin cake-batter-like dough into a thick clay pot about the size of a large vase. After the dough had risen the pot was placed in a hole dug in the embers of a fire. A second pot was heated and placed on top of the first pot, and together the two pots created an "oven environment. A small sculpture from ancient Egypt shows a man rolling dough on his hands and knees.

Based on modern experiments scientists determined the bread was baked for around an hour and 40 minutes and a cone-shaped loaf of bread was removed by running a knife along the inside of the pot. The bread was heavy and as nutritious as modern store-bought bread. One of the scientist who participated in making bread described it as "sourdough bread the way it's meant to taste."

Describing the result of his effort to make bread the ancient Egyptian way, archaeologist Mark Lehner told National Geographic: "We did produce edible bread from various combinations of barely and emmer, albeit a bit too sour even for most sourdough tastes because we let he dough sit too long before baking. Each of our loaves was heavy and massive, large enough to feed several people at one

See Separate Article: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN BREAD africame.factsanddetails.com

Women's Occupations in Ancient Egypt

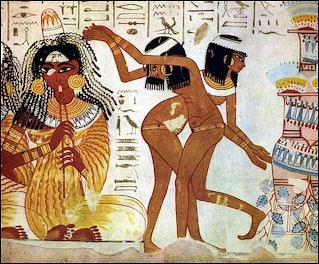

women weaving

Career options for women were limited. Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times, “Women might find work as professional mourners--one sees a cluster of them gesturing and wailing in a funerary carving--or as performers in court and temple rituals. In a relief from the tomb of a Middle Kingdom queen, female musicians raise frondlike hands in the air as they clap out a rhythm.

Peter A. Piccione wrote: “In general, the work of the upper and middle class woman was limited to the home and the family. This was not due to an inferior legal status, but was probably a consequence of her customary role as mother and bearer of children, as well as the public role of the Egyptian husbands and sons who functioned as the executors of the mortuary cults of their deceased parents. It was the traditional role of the good son to bury his parents, support their funerary cult, to bring offerings regularly to the tombs, and to recite the offering formula. Because women are not regularly depicted doing this in Egyptian art, they probably did not often assume this role. When a man died without a surviving son to preserve his name and present offerings, then it was his brother who was often depicted in the art doing so. Perhaps because it was the males who were regularly entrusted with this important religious task, that they held the primary position in public life. [Source: Peter A. Piccione, College of Charleston,“The Status of Women in Ancient Egyptian Society,” 1995, Internet Archive, from NWU -]

“As far as occupations go, in the textual sources upper class woman are occasionally described as holding an office, and thus they might have executed real jobs. Clearly, though, this phenomenon was more prevalent in the Old Kingdom than in later periods (perhaps due to the lower population at that time). In Wente's publication of Egyptian letters, he notes that of 353 letters known from Egypt, only 13 provide evidence of women functioning with varying degrees of administrative authority. -

“On of the most exalted administrative titles of any woman who was not a queen was held by a non-royal women named Nebet during the Sixth Dynasty, who was entitled, "Vizier, Judge and Magistrate." She was the wife of the nomarch of Coptos and grandmother of King Pepi I. However, it is possible that the title was merely honorific and granted to her posthumously. Through the length of Egyptian history, we see many titles of women which seem to reflect real administrative authority, including one woman entitled, "Second Prophet (i.e. High Priest) of Amun" at the temple of Karnak, which was, otherwise, a male office. Women could and did hold male administrative positions in Egypt. However, such cases are few, and thus appear to be the exceptions to tradition. Given the relative scarcity of such, they might reflect extraordinary individuals in unusual circumstances. -

“Women functioned as leaders, e.g., kings, dowager queens and regents, even as usurpers of rightful heirs, who were either their step-sons or nephews. We find women as nobility and landed gentry managing both large and small estates, e.g., the lady Tchat who started as overseer of a nomarch's household with a son of middling status; married the nomarch; was elevated, and her son was also raised in status. Women functioned as middle class housekeepers, servants, fieldhands, and all manner of skilled workers inside the household and in estate-workshops. -

“Women could also be national heroines in Egypt. Extraordinary cases include: Queen Ahhotep of the early Eighteenth Dynasty. She was renowned for saving Egypt during the wars of liberation against the Hyksos, and she was praised for rallying the Egyptian troops and crushing rebellion in Upper Egypt at a critical juncture of Egyptian history. In doing so, she received Egypt's highest military decoration at least three times, the Order of the Fly. Queen Hatshepsut, as a ruling king, was actually described as going on military campaign in Nubia. Eyewitness reports actually placed her on the battlefield weighing booty and receiving the homage of defeated rebels. -

Careers for Women in Ancient Egypt

dancers

Dr Joann Fletcher of the University of York wrote for BBC: “In fact, other than housewife and mother, the most common 'career' for women was the priesthood, serving male and female deities. The title, 'God's Wife', held by royal women, also brought with it tremendous political power second only to the king, for whom they could even deputise. The royal cult also had its female priestesses, with women acting alongside men in jubilee ceremonies and, as well as earning their livings as professional mourners, they occasionally functioned as funerary priests. [Source: Dr Joann Fletcher, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Their ability to undertake certain tasks would be even further enhanced if they could read and write but, with less than 2 percent of ancient Egyptian society known to be literate, the percentage of women with these skills would be even smaller. Although it is often stated that there is no evidence for any women being able to read or write, some are shown reading documents. Literacy would also be necessary for them to undertake duties which at times included prime minister, overseer, steward and even doctor, with the lady Peseshet predating Elizabeth Garret Anderson by some 4,000 years. |::|

“By Graeco-Roman times women's literacy is relatively common, the mummy of the young woman Hermione inscribed with her profession 'teacher of Greek grammar'. A brilliant linguist herself, Cleopatra VII endowed the Great Library at Alexandria, the intellectual capital of the ancient world where female lecturers are known to have participated alongside their male colleagues. Yet an equality which had existed for millennia was ended by Christianity-the philosopher Hypatia was brutally murdered by monks in 415 AD as a graphic demonstration of their beliefs. |::|

“With the concept that 'a woman's place is in the home' remaining largely unquestioned for the next 1,500 years, the relative freedom of ancient Egyptian women was forgotten. Yet these active, independent individuals had enjoyed a legal equality with men that their sisters in the modern world did not manage until the 20th century, and a financial equality that many have yet to achieve. |::|

People Paid to Become Temple Servants In Ancient Egypt

Rather than become forced labor, some ancient Egyptians allowed themselves to become virtual slaves and paid to become temple servants. Colin Schultz wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Ancient Egypt was fueled by forced labor. Not the construction of the pyramids, mind you, but other grand projects, such as quarries and roads and water infrastructure. Most Egyptians, says the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, were drawn in for forced labor duty, a process known as corvée: “forced labor as a form of taxation. ” But not everyone. Some people, says research by Kim Ryholt at the University of Copenhagen, bought their way out of the hard life by turning themselves into temple servants. [Source: Colin Schultz, Smithsonian magazine, January 9, 2013]

In Nature, Hazem Zohny describes the ancient Egyptians as volunteering themselves — in fact, paying their own way — to become temple slaves. Ryholt’s research describes the situation a bit differently, suggesting they were making “self-dedications” to become a temple “servant. ” One of these pledges, translated, reads:

Ptolemy, living forever.

great god, . .,whose mother is Tahôr:

servant from this day onwards until eternity, and I shall give

as servant fee before Anubis, the great god.

t, an ancient one, a demon, a great one, any on earth

to exercise authority over her

Written in regnal-year 23, second month of shemu, day 1.

The reason anyone would volunteer themselves — and pay for the privilege — to become a temple servant, says NatuRas Zohny, comes back to Egypt’s forced labor taxation, the corvée: While these contracts bound them as slaves, they also protected them from being subject to forced labors such as digging canals and other harsh and often fatal projects. However, as temple slaves, they were mainly engaged in agriculture and were exempt from forced labor.

According to researcher Ryholt, the people who made these pledges were generally from lower class families. In view of this and the low social status of the majority of supplicants, it may be argued that the self-dedications were the legal instruments of a symbiotic relationship. On one hand, certain people able to pay a monthly fee could exploit the law by acquiring the status of temple servants in order to avoid compulsory labor, this apparently being considered the lesser of two evils. On the other, temples could in turn exploit this circumstance and generate both a modest income and enjoy the benefits of an expanded workforce. In effect the temples thus came to provide a form of asylum – against payment! –for individuals that might be subjected to hard forced labor.

Obviously not everyone working at the temple was fleeing from forced labor, but the symbiotic benefit would be attractive for many. According to Zohny, however, “This loophole for escaping forced labor was likely only open during a 60 year period from around 190 B.C. to 130 B.C., with no other evidence that this practice existed during other periods in ancient Egypt. Ryholt speculates that this is because reigning monarchs could not afford losing too many potential laborers to temples in the long-run. ”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024