Home | Category: Life (Homes, Food and Sex)

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN SHOES AND SANDALS

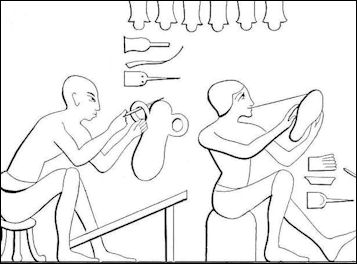

cobblers at work Ancient shoes where generally made from woven palm leaves, vegetable fibre or papyrus and were kept in place on the foot with linen or leather bands. Some of the earliest known shoes from the Old World are sandals made from papyrus leaves found in an Egyptian tomb dated at 2000 B.C. A leather sandal dated to 1300 B.C. has also been found in Egypt. Sandal-makers depicted in tomb paintings went about their duties like 19th century cobblers.

Sandals and shoes were worn mainly the rich. One very old image shows a nobleman walking barefoot followed by a servant carrying his shoes. Ordinary people often went barefoot. Egyptians exchanged sandals when they exchanged property or authority. A sandal was given to a groom by the father of the bride.

Egyptian costume, as far as we have already considered it, shows a comparatively rich development; on the other hand the history of the foot gear is very simple. At a time when people paid great attention to the various gradations of style in clothes and wigs, and when they were also strenuously striving after greater cleanliness, men and women, young and old almost always went barefoot, even when wearing the richest costumes. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Under the Old and the Middle Kingdom women seem never to have worn sandals, while great men probably only used them when they needed them out of doors, and even then they generally gave them to be carried by the sandal-bearer who followed them. Sandals were more frequently used under the New Kingdom; still they were not quite naturalised, and custom forbade that they should be worn in the presence of a superior. Consequently sandals were all essentially of the same form. Those here represented have soles of leather, of papyrus reed or palm bast, the two straps are of the same material; one strap passes over the instep, the other between the toes. Sometimes a third strap is put behind round the heel in order to hold the sandal on better; sometimes the front of the sandal is turned over as a protection to the toes. The sandal with sides belongs perhaps to a later period, it approaches very nearly to a shoe.

See Separate Article: EARLIEST CLOTHES AND SHOES europe.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Footwear in Ancient Egypt: the Medelhavsmuseet Collection” (English and Arabic Edition) by Dr. Andre J. Veldmeijer (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Book of the Feet; a History of Boots and Shoes, With Illustrations of the Fashions of the Egyptians, Hebrews, Persians, Greeks and Romans” by Joseph Sparkes Hall (1847) Amazon.com;

“Leatherwork from Elephantine (Aswan, Egypt): Analysis and Catalogue of the Ancient Egyptian & Persian Leather Finds” by Dr. Andre J. Veldmeijer (2016) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun's Footwear: Studies of Ancient Egyptian Footwear” by Andre J Veldmeijer (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptian Footwear Project: Final Archaeological Analysis” by Dr. André Veldmeijer (2019) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian & Persian Costume” by Mary Galway Houston (1920) Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

3500- and 2000-Year-Old Egyptian Shoes

In April 2020, Spanish and Egyptian archaeologists announced that they uncovered a teenager who was only 15 or 16 years old when she died during the 17th dynasty (1580 B.C. to 1550 B.C. along with one of the world’s oldest pairs of leather shoes, José Galán, director of the archaeological mission, said. Laura Geggel wrote in Live Science: The excavation team found a pair of leather sandals and leather balls tied together with a string, which also dated to the 17th dynasty. "The sandals are in a good state of preservation, despite being 3,600 years old," Galán said. These shoes were dyed red and engraved with images of the god Bes, the goddess Taweret, a pair of cats, an ibex and a rosette, according to Ahram Online. Based on the sandals' size and decorations, it's likely that they belonged to a woman, Galán said. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, April 29, 2020]

In the 2010s, Archaeologists discovered seven shoes, that appear to be made out of cow leather, within a jar in an Egyptian temple. The shoes are more than 2,000 years old. Two pairs were meant for children were wrapped within a larger isolated adult shoe using palm fiber string. The adult shoe was 24 centimeters (nine inches) in length. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, February 26, 2013]

Live Science reported: The isolated shoe has the earliest known example of a "rand" a folded leather strip that goes between the sole of the shoe and the upper part, reinforcing the stitching and making the shoe more watertight. In the dry climate of ancient Egypt it would not have been as useful a device and its presence suggests that the seven shoes may have been made abroad.

The shoes were closed using a tailed toggle system with leather strips forming knots which were passed through openings to close the shoes. A strip of leather would hang down, decoratively, from either side of each knot. The shoes were relatively expensive, possibly foreign made and would have been a sign of status.

All the shoes have a similar cutting pattern although the child shoes do not have a strip and the isolated shoe has a rand rather than a strip. When André Veldmeijer analyzed the pair he found that the left had more repairs than the right. This indicates that the person who wore them walked with a limp.

Shoemakers in Ancient Egypt

The shoemaker now takes the prepared leather, and puts it on his sloping work-table, and cuts it into soles or straps: for this purpose he uses the same kind of knife with the curved blade and short handle which is in use at the present day. The necessary holes are then bored with an awl, and the straps are drawn through. The workman was accustomed to do this with his teeth. After being fastened with knots, the simplest form of sandal was complete. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

We possess small monuments erected by shoemakers of the time of the New Kingdom, which prove to us that these tradesmen held a certain social position. The most remarkable of these is the small statue of a “chief of the shoemakers," representing this gallant kneeling, dressed in the sliend'ot which, During the New Kingdom, the higher craftsmen had a right to wear. The learned poet of old certainly overdrew his picture when he thus wrote of the shoemaker: “He is very wretched, he is always begging, and (alluding evidently to the custom of drawing the straps through with the teeth) what he bites is (only) leather. "'

Ancient Egyptian Hats, Gloves and Coneheads

Nefertari Egyptians generally didn't wear hats it seems. They sometimes wore hair bands to keep their hair out of their face of wigs. Egyptian noblemen used parasols, carried by slaves for protection from the sun. The Egyptians didn't need gloves for warmth, but women wore soft linen gloves, sometimes embroidered with colored threads, as a decorative accessory. Children often went nude until they were teenagers.

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: Egyptologists have long been puzzled by a type of figure in ancient Egyptian art depicted wearing an unusual kind of conical hat. These figures often appear in scenes depicting banquets, funerary rituals, or interactions with the gods. Scholars assumed that these strange headpieces were symbolic artistic devices, since no archaeological evidence of them had ever been uncovered. [Source:Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2020]

But new excavations of two burials dating to between 1347 and 1332 B.C. in Amarna have yielded proof that these headpieces did, in fact, exist. One hat was found atop the head of a female in her twenties, while the other belonged to a 15-to-20-year-old individual of undetermined sex.

Analysis of the cones indicates that they were made of beeswax, perhaps molded around a textile lining. Experts are still unsure why some Egyptians wore the headpieces, or what they represent. “It’s probably wrong to think that there is one definitive answer as to the function and use of the cones,” says Monash University archaeologist Anna Stevens. “It seems that they placed the wearer in a special state, particularly a purified state, which was especially suitable when seeking out the company or assistance of divinities. ”

Leather in Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt was exceedingly rich in skins, the result of the stockbreeding so extensively carried on in that country. The inhabitants were well aware of their value; they considered the skin indeed to be such an important part of the animal, that in their writing the sign of a skin indicated all mammiferous animals. Beautiful skins, especially such as were gaily spotted, were never denuded of the hair, but were manufactured into shields, quivers, and clothing, or were employed in the houses as coverings for seats. The “skins of the panther of the south “were valued very highly; they were brought from the upper Nile and from the incense countries. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Less valuable skins, such as those of oxen, gazelles, etc., were manufactured into leather; the leathern objects which have been found in the tombs prove to what a degree of excellence this industry attained, especially During the New Kingdom. Of this period our museums possess examples of every kind of leather — coarse leather and fine leather, the former manufactured into sandals, the latter into aprons and straps; white leather made into a kind of parchment and used like the papyrus for writing material; also fine colored leather stamped with an ornamental pattern which was used for the ends of linen bands.

We are not completely sure what process the Egyptians used in the dressing of skins, though pictures of all periods represent men working at the leather trade. We first see how they soften the leather in great vessels, how they then beat it smooth with a stone, and-finally stretch and pull it with their hands over a three-legged wooden frame until it has attained the necessary suppleness.

Leatherworking in Ancient Egypt

André J. Veldmeijer of the Netherlands Flemish Institute in Cairo wrote: “Leather was used throughout Egypt’s history, although its importance varied. It had many applications, ranging from the functional (footwear and wrist-protectors, for example) to the decorative (such as chariot leather). Although leather items were manufactured using simple technology, leatherworking reached a high level of craftsmanship in the New Kingdom. Among the most important leather-decoration techniques employed in Pharaonic Egypt, and one especially favored for chariot leather, was the use of strips of leather of various colors sewn together in partial overlap. In post-Pharaonic times there was a distinct increase in the variety of leather-decoration techniques. Vegetable tanning was most likely introduced by the Romans; the Egyptians employed other methods of making skin durable, such as oil curing.” [Source: André J. Veldmeijer, Netherlands Flemish Institute Cairo, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“The term “leather” refers to skins that have been tanned or tawed—that is, converted into white leather by mineral tanning, as with alum and salt—rather than cured. In Egypt it appears that skins were not tanned or tawed in the Pharaonic Period; however, thus far we lack detailed, systematic chemical analyses from which to make a conclusive determination. Skins and leather were used throughout Egyptian history, but their importance and quality varied. According to Van Driel- Murray, skins were widely used in the Badarian and Amratian (Naqada I) periods but were largely superseded by cloth in the Gerzean (Naqada II).

ancient Egyptian leatherworkers

“In the Old and Middle kingdoms the use of leather declined in favor of the use of fiber and textiles; skins seem to have been of secondary importance to meat and the production of glue. The Nubian “pan-grave” cultures, however, introduced decorated leather garments, including the loincloth, and containers and pouches of high quality, not dissimilar to those of Predynastic traditions and comparable to leatherwork recovered from other Nubian sites, such as Kerma. During the New Kingdom leather was much more widely used. New weapons technology—such as the introduction of the chariot by Asiatic peoples—was partially responsible for this. Contact with foreign cultures might also have been the reason for the introduction of the leather shoe. It is difficult to say whether the use of leather continued to the same extent into the Third Intermediate Period. The situation in the Late and Ptolemaic periods is as enigmatic. Better attested is leather from the Roman Period, during which the use of vegetable-tanned leather became widespread and in which innovations in technology are apparent.

“In Egypt leather was most commonly made from the skins of cow, sheep, goat, and gazelle, although those of more exotic species such as lion, panther, cheetah, antelope, leopard, camel, hippopotamus, crocodile, and possibly elephant have been identified. Leather was used in a wide variety of items, ranging from clothing, footwear, and cordage, to furniture and (parts of) musical instruments.

Processing of Skins Into Leather in Ancient Egypt

André J. Veldmeijer of the Netherlands Flemish Institute in Cairo wrote: “The processing of skins into leather is virtually universal and is well documented. Scenes from the tomb of Rekhmira provide especially useful information. According to Forbes’s analysis of leather processing, after a skin was flayed, underlying fat and hair were removed by rubbing urine, ash, or a mixture of flour and salt into the haired surface. Next, the skin was cured, arresting the degenerative process.[Source: André J. Veldmeijer, Netherlands Flemish Institute Cairo, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“Curing in oil seems to have been the preferred method in Pharaonic Egypt, although mineral curing was probably practised, particularly in the Predynastic Period. After having been soaked in oil, the skin was staked to make it supple and the remaining oil was worked into the skin. Finally, the skin would be dried. Although vegetable tanning is the only means of producing chemically stable leather, current scholarly opinion maintains that tanning was unknown in Egypt before the Greco-Roman Period. An explanation for this may be that the Romans, who had experienced a comparatively wetter environment that required them to adopt the use of vegetable-tanned leather, brought the technique to Egypt, where the arid climate had not rendered tanning a necessity. However, Nubian leatherwork, including leatherwork of the Nubian C-Group at Hierakonpolis, differs from Egyptian leatherwork in many respects, one of which seems to be its processing methods, which possibly included vegetable tanning. Indeed the results of a field test for vegetable tanning were convincingly positive. Problems with the test have been noted, however; its further analysis, currently in progress, is needed. Furthermore, the question as to why vegetable tanning may have been employed in Nubia remains to be answered.”

Leather Manufacturing and Tools in Ancient Egypt

André J. Veldmeijer of the Netherlands Flemish Institute in Cairo wrote: “Leather-manufacturing techniques were basic: leather goods were sewn with simple, but varied, seams, using flax, sinew, or narrow leather thongs. Rawhide (unprocessed skin) was generally used for lashing, as it shrinks upon wetting and thus tightens the components of the object being fastened. Rawhide was therefore employed to fasten ax blades onto their shafts and to form the “joints” of furniture. Because of its hardness and durability, it was sometimes used to provide the soles of footwear. Despite the simplicity of manufacturing techniques, some Egyptian leatherwork reached a high level of craftsmanship. [Source: André J. Veldmeijer, Netherlands Flemish Institute Cairo, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“Before the New Kingdom, mineral dyes were used to color leather. The complete palette of colors used is hard to establish, as some shades are more susceptible to discoloration than others—such as blue, apparently, given its few surviving examples. Abundantly used were bright red and green, often in combination. Shoes very similar to the one depicted have been found in Deir el Medina and date to the New Kingdom.

“White may have been obtained by manipulation of the skin surface, already pale due to processing, with pastes of chalk mixed with fats. Vegetable dyes, such as madder (red), indigo (blue), and pomegranate (yellow and black), with alum as a mordant, appeared after the 18th Dynasty. Gilding came into use as late as the Coptic Period. Several other techniques of leather-decoration were also used: decoration with beads is known from as early as the Predynastic Period; cutting (incision) was featured from the Old Kingdom onward; and stamping and multicolor appliqué are known starting from the New Kingdom.

“Leatherworking tools included large pots for dipping, the trestled beams used for staking, and the low stools and platforms upon which much of the processing was carried out. Needles of bone and probably copper were used for stitching leather from the earliest times. Leather may have been pricked prior to stitching in order to facilitate penetration with a needle; awls of bone (later of metal) and marlin spikes would have been used for this purpose.

“Most leather cutting was performed using curved knives with either broad or narrow blades. Pounders for smoothing, depilation, and working in oils and fats would also have been widely used. Slickers—that is, blades with triangular anti-clogging holes—may have been used for any of the above-mentioned purposes and would have been preceded by the flint scraper. Tools for incised decoration would have been necessary: there are many examples of pointed tools that could have served this purpose. Stamps would probably have been cast from metal or carved from stone, or possibly wood, although no such examples have been identified as yet. It is archaeologically difficult to confirm the presence of tanning pits. A possible leather workshop from the Greco-Roman Period was excavated at Akoris.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024