CERAMICS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Naqaqa black vase

Pottery making was well advanced by 3000 B.C. The earliest Egyptian pottery was unglazed red earthenware. Both Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt had the pottery wheel by that time. The potter’s wheel is believed to have been invented in Mesopotamia around 3500 B.C. and may be tied to the invention of wheeled vehicles. See Mesopotamia.

The Egyptians developed fairly sophisticated chemistry through cosmetic-making, dying, glassmaking and gold and iron metallurgy. Ceramic objects could be decorative, used in daily life or have religious significance. Bottles, jars and jugs used to carrying things and for storage were often made of fired clay. Decorative pottery was sometimes covered with a blue glaze. Many types of ornamental pottery were made for royalty and aristocrats. Even beads and jewelry were made of clay.

Paul T. Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: “Pottery is usually the most common artifact on any post- Mesolithic site. In Egypt its abundance can fairly be described as overwhelming, and it generally requires substantial resources in order to be properly recorded by excavators. Pottery was the near- universal container of the ancient world and served those purposes for which we might now use plastics, metal, glass and, of course, modern ceramics. Its abundance in the archaeological record is not due merely to its wide use, but to its near indestructibility, and this is in turn a facet of its technology. [Source: Paul T. Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

““Pottery represents one of the earliest complex technologies—that of changing a plastic material, clay, into an aplastic material, ceramic, more colloquially known as pottery. In order to produce pottery it is necessary to obtain clay, either from a water course or sometimes by mining, and to process it by adding “opening materials” (“temper”) to improve its working properties, or by removing materials such as calcite.

Egyptian ceramics resisted the influence of pottery from of Europe. The obstinacy with which Egypt clung to the forms of its pots and bowls is most remarkable. For this reason nothing in Egypt is so more difficult to date as pottery, for potsherds which are centuries apart in point of date, have almost identical characteristics. The modern grey ware of Keneh or the red ware of Aysut might almost be mistaken for pottery of the New Kingdom. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Origins and Use of the Potter’s Wheel in Ancient Egypt” by Sarah Doherty (2015) Amazon.com;

”A Manual of Egyptian Pottery, Volume 1: Fayum A - A Lower Egyptian Culture”

by Anna Wodzinska (2011) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries” by A. Lucas and J. Harris (2011) Amazon.com;

“'Make it According to Plan': Workshop Scenes in Egyptian Tombs of the Old Kingdom” by Michelle Hampson (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Technology and Innovation” by Ian Shaw (2012)

Amazon.com;

“Beni Hassan: Art and Daily Life in an Egyptian Province” by Naguib Kanawati and Alexandra Woods (2011) Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Potters in Ancient Egypt

In contrast to carpenters, who suffered from shortages of rare materials, potters had a wealth of the raw material at their command. In all parts of Egypt good clay was to be found for ceramic ware. The earthenware prepared by the potter was almost always of the simplest description; the pots, bottles, and bowls were without any glaze or ornamentation of any kind, except a few lines of paint; they made dolls also, and similar rude figures. The beautiful pottery and the artistic terra-cotta figures of Greece were quite unknown to the more ancient Egyptians. '

Paul T. Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: The clay, or mixture of clay and other materials, was shaped either by hand-forming, using the potter’s wheel, or by molding. The finished form is then dried. This is the last point at which the potter could rework the material by simply adding water to it. Once dry, the material is fired either in the open or in a kiln. Firing leads to the fusion of the clay platelets, which renders the material aplastic. It is the sherds of this aplastic material that are most commonly encountered in the archaeological record. [Source: Paul T. Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

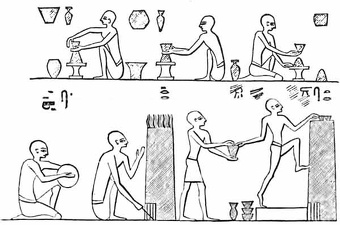

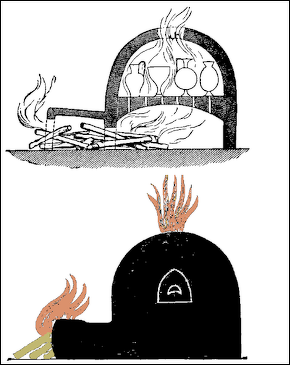

Various pictures of the time of the Old and the Middle Kingdom show us the potter at work. It was only the simplest vessels that were formed entirely by the hand. As a rule the potter's wheel was used, which was turned by the left hand, whilst the right hand shaped the vessel. The pots were then burnt in a stove which seems to have resembled that used by the Egyptian bakers. As is shown in our illustration, the fire was below, and the pots were placed either on the top or inside; in another picture we see the pots standing on the top apparently covered with ashes. '''

An image of potters of the Middle Kingdom in the Beni Hasan tomb shows four men at the potter's wheel: the first one turns it, the second cuts off the pot that is finished, the third one takes it down, the fourth begins a new one. Below is showing the shaping of a plate with the hand, two furnaces, and the carrying away of the pottery that is finished.

Pottery-Making Clay in Ancient Egypt

Paul T. Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: “The raw material for producing pottery is clay. Egyptologists have distinguished two main types of clay for indigenous Egyptian ceramics: Nile silt and marl obtained from the desert. As the name suggests, Nile silt clay comes from the Nile River. Strictly speaking it is a misnomer, since to a geologist “silt” and “clay” refer to two different particle-size fractions. For the Egyptologist it is simply a convenient way of distinguishing this riverine, alluvial clay—which is rich in iron and so fires to a red color in an oxidizing atmosphere—from the marl clays. [Source: Paul T. Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Marl clays usually contain at least 10 percent calcium carbonate (lime), and in field tests can be distinguished using a 10 percent solution of hydrochloric acid, to which they react by effervescing. Marl clays normally fire to a cream or buff surface. This surface starts to form during the drying of the vessel, when the calcium carbonate begins to effloresce on the vessel’s surface, in the same manner as the glaze in effloresced faience.

“Whereas Nile clays can be obtained virtually anywhere along the course of the Nile and are therefore widely available, the occurrence of marl clays is much more limited, being confined to a few main localities, notably around the Qena area of Upper Egypt. In these localities the marl is quarried or mined as though it were a rock and generally arrives at the workshop as solid blocks that must be broken up, soaked, and trampled in order to produce a workable clay. Veins of calcite frequently occur in marl deposits, and any pieces of calcite that are included in the clay mixture are carefully removed by those treading the clay, since to leave them in may lead to flaws in the vessel. This refining of the clay by picking out aplastic material may also be applied to Nile silt, which may contain undesirable pieces of shell, small stones, and other debris.”

Clay Preparation of Pottery in Ancient Egypt

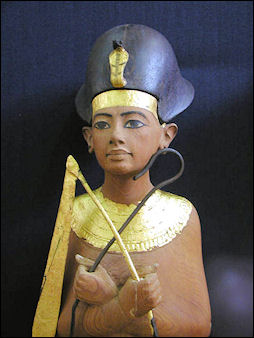

Tutanhkamun Shabti Paul T. Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: “The amount of preparation given to the clays is, to some extent, dependent upon their final use. Coarse utilitarian wares may require relatively little cleaning. As well as the cleaning of clays, it is frequently necessary to make additions to their mixture in order to enhance their working properties. These additions are usually referred to as “temper” or “filler” by archaeologists, although potters use the term “grog.” “Opening materials” might be a more suitable term. For example, some clays, or mixtures thereof, may be too sticky to handle well and so have another material such as sand added to them. This has the effect of reducing their plasticity somewhat, as well as “opening” the clay fabric so that air can penetrate it and help it to dry more evenly. [Source: Paul T. Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Such open clay bodies may also fire more readily with simple technology, in that the more coarse fabric allows the escape of steam as the moisture is driven out of the clay during the firing process. A coarse body requires only simple kiln control; a finer one may require careful handling during the firing process if the vessel is not to become bloated and deformed as a result of the buildup of steam in the fabric. In addition to sand, it is possible to use crushed rock fragments, pieces of fired pottery, and plant fibers or hair. Dung can also be added, which brings with it plant material. Chopped straw or chaff may be used where an open-textured fabric is required, since it burns out during firing to leave voids. These voids help to prevent the propagation of large cracks, as well as allow the fabric to heat quickly, or to “sweat”—the evaporation thus enabling the vessel to keep any water stored within cool and fresh.

“Porous fabrics, be they silt or marl, are suitable for the storage of water. The amphora-like “Ballas jar,” still made from marl clay in the Qena/Ballas region of Upper Egypt, has been made in much the same form since Roman times. The porous clay allows the transport and short-term storage of water: the vessel “sweats” gently in the sun, the resulting evaporation helping to keep the water cool. The same principle is true of a whole range of present-day Nile silt-ware vessels, including the coarse straw-tempered gidr used in Middle Egypt, and the ubiquitous zir vessels for the longer-term storage of water, which are frequently found outside houses for the convenience of guests and travelers. Similar vessels seem to have served the same purpose in ancient times; zir emplacements are a common feature of the archaeological record.

“Some authors have argued for the levigation of ancient Egyptian clays and have cited tomb scenes as supporting this view. The levigation process involves the mixing of clay with large volumes of water (in a large container, such as a tank), followed by a period of settlement whereby the coarsest fraction of the clay settles to the bottom first, allowing the finer fraction to then be skimmed off so that a fine and uniform clay is produced. The tomb scene most frequently regarded as showing this process is in the tomb of Kenamun at Thebes, where a man is shown—apparently— wading in a tank. This would, in fact, stir up the clay again, defeating the object of levigation. The scene should rather be considered as showing the treading of clay, which helps to homogenize the mixture and drive out air.”

Pottery Vessel Forming in Ancient Egypt

Paul T. Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: “Once prepared, the clay must be formed into a vessel. Although there are many methods by which this can be achieved, they are divided into two main groups: hand forming and wheel forming. Arnold and Bourriau have established a three-fold scheme for the development of pottery forming in Egypt, using “non-radial,” “free-radial,” and “centered-radial” techniques, according to how radial symmetry (that is, the walls being at an equal distance from the vertical axis of the vessel) is incorporated. Non-radial methods treat the vessel as though it were a piece of sculpture and essentially model it without reference to a particular vertical axis. In the free-radial method the pot might be constructed by coiling or rotating intermittently as the clay is drawn up to form the walls. Centered-radial techniques involve a rotating support with a fixed central axis—the potter’s wheel. The rotation of this device at speed allows the use of centrifugal force to help in the drawing up and shaping of the vessel. [Source: Paul T. Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“In practice, techniques might be combined so that, for example, a vessel made by coiling is given a rim made on the wheel. However, historically there was an increasing tendency for vessels to be wheel made. There are numerous ways in which vessels may be shaped within each technique. Among the non-radial methods, Arnold and Bourriau define pinching and hollowing, paddle and anvil, shaping on a core or over a hump, and shaping in a mold. All of these methods were in use by the mid-18th Dynasty, but some were employed only for relatively specialized vessels. For example, bread molds were frequently made by pressing the clay over a core, known as a “patrix,” which gives the interior of the vessel its shape and smooth surface. The technology is simple and requires little skill. It is not unlikely that unskilled potters may have produced these bread molds in close proximity to bakeries, since that would have been more efficient than transporting large numbers of fired vessels. The paddle and anvil technique, in which a bat, or paddle, is used to beat the clay against an anvil (often no more than a round stone) in order to thin the clay and draw it up, enjoyed wide use from Predynastic times and was often used in association with coiling, which is a free-radial method.

Canopic jars

“The free-radial methods include slab- building, coiling—sometimes in association with a simple wheel—and turning on a turn- table. This latter might be used with various non-radial methods. All were known by the Archaic Period/early Old Kingdom. Arnold and Bourriau differentiate between types of wheel and whether they are rotated by hand or “kicked” by movement of the foot. All wheels, however, are capable of producing pottery using centrifugal force, as has been demonstrated in experiments by Powell. The first known wheels appear in the Old Kingdom (Dynasty 5 or 6), with the kick- wheel perhaps appearing in the Late Period. It has been supposed that the introduction of the potter’s wheel necessitated the use of a finer paste than that required by the hand- making techniques. However, this is not necessarily true. Many Egyptian potters of the present day use very coarse clays, with sharp inclusions, but work the clay very wet, with the wheel revolving relatively slowly, so that any sharp inclusions are easily pressed into the clay body by the pressure of the hands without causing undue abrasion.”

Firing of Ancient Egyptian Pottery

Paul T. Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: “There is a relationship between the fabric of a vessel, its firing technology, and its intended function. Generally speaking, fine clays require more careful firing, in a more controlled regime, than coarse ones. Fine clays are also generally more suitable for the application of painted decoration, or for service as prestigious table-wares. The same fine nature that makes them unsuitable for firings where the temperature rises quickly also makes them unsuitable as cooking vessels, as rapid heating leads to differential thermal expansion with resultant cracking of the vessel. Thus, for example, marl clays were often used in the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.) for high quality table-wares and for producing amphorae for the storage of wine. The surfaces of these marl vessels are often carefully slipped and burnished—that is, compressed with a smooth stone or piece of hard leather so that they are shiny and less porous. The finely burnished surfaces of some marl clays, and indeed of some Nile silt clays as well, can be mistaken for glazing by those unfamiliar with Egyptian pottery, which is not glazed before the Roman Period. Coarse fabrics, frequently silts, can be fired in a relatively uncontrolled way, with a rapid rise in temperature. The porous nature of the final product renders it well suited for use as a cooking vessel, since the numerous small cracks that developed during firing (as a result of the burning out of organic material sometimes added as temper) prevent the propagation of larger cracks. [Source: Paul T. Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Ancient Egyptian-style kiln

“Firing is the means by which the transformation from the plastic clay to the aplastic ceramic is achieved, and there are a variety of ways by which the process can be carried out. The simplest method is sometimes called “bonfire firing.” As the name suggests, the fuel is piled over and around the unfired vessels. Once the fuel is lit there may be almost no control over the firing, but experience allows suitably fired pots to be produced. However, there are numerous ethnographic examples of potters using this technique with great care, positioning vessels in particular parts of the fuel heap, and building elongated heaps such that the wind drives the heat back toward the rearmost pots, which require the longest firing but perhaps the slowest initial heating. In this way fine vessels might be produced. Little is known of the means by which the extremely fine black-topped red ware of the Naqada Period was produced, but it was surely the product of open firing. The makers of this ware were able to fire it sufficiently to produce a hard fabric, but not at so high a temperature that the burnished surface was degraded. They also managed to produce a vessel whose lower part was oxidized red, while the upper part was black as a result of reducing (oxygen deficient) conditions at the end of the firing. This may have been achieved by inverting the hot vessel in sand or vegetable matter at the end of the firing.

“A more usual way to control firing, however, is the kiln. Among the advantages of this structure over open firing is that the fuel can be separated from the vessels, thereby preventing their discoloration from contact with the fuel and avoiding localized areas of reduction/oxidation. The structure also protects vessels from the wind. Furthermore, if partially sunk into the ground, it can provide insulation, allowing for firing for longer periods or at higher temperatures without significant increases in fuel, as well as easier manipulation of the kiln atmosphere and more controlled cooling.

“Ancient Egyptian kilns were invariably of the updraft type—that is, the fire was located beneath the stack of vessels, which were separated from it by a gridded floor or “chequer.” The hot gases (the draft) would pass up through the chequer and so heat the pots stacked above it. Vessels were frequently fired mouth-down so that each filled with hot gases, thereby slowing the passage of the heat through the kiln and increasing its effectiveness. As the stack of vessels heated up, the vessels themselves radiated heat. The heat trapped within the kiln helped to fire the vessels more effectively.

“Ancient Egyptian kilns are depicted in a number of tombs, such as that of Bakt III at Beni Hassan (BH15), where they appear to have been open-topped, rather than having a sealed dome. The top would probably have been covered with a layer of broken pottery, as is the case with most contemporary Egyptian kilns. Such covering serves to provide some insulation, but equally importantly serves as a layer on which soot collects. At the end of the firing, after the kiln has cooled, the layer of blackened sherds is removed and the cleanly fired pots are removed from the kiln.”

Kilns and Firing Structures in Ancient Egypt

early Greek potters' kiln

Paul Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: “The purpose of firing pottery is to change clay, a plastic material, into ceramic, which is aplastic. Examined here are structures designed to fire pottery or faience or to make glass (although the latter might be better described as furnaces). Firing can take place in an open, bonfire-like environment, which can also be enclosed as a firing structure. Beyond this is the development of the true kiln of which there are two main types: updraft and downdraft. The first of these is by far the most common on archaeological sites throughout the world dating to before the nineteenth century CE. Here the firing technology of ancient Egypt is discussed in particular. [Source: Paul Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Pottery is fired in order to effect the change from clay, a plastic material, into aplastic ceramic. This is done by first evaporating the water that lubricates the clay platelets and renders the clay malleable, then driving off the water that is chemically combined in the clay mineral structure. The clay platelets subsequently begin to fuse together at their edges in a process known as “sintering.” This is the first stage in vitrification and varies according to the clay type but usually begins between 600°C and 700°C. If continued to higher temperatures the clay would eventually become fully vitrified and collapse after becoming essentially molten. Firing aims to sinter the material to a point below complete vitrification, so rendering the clay ceramic.

“The history of the kiln is a history of improvements or changes to the way that pottery is fired and encompasses arrangements that would not strictly qualify as “kilns.” Holthoer has attempted to provide a fourfold classification of kilns, but this has not gained wide acceptance and is inconsistently applied in his examples. A simpler classification has been proposed, making three broad distinctions: 1) open firing; 2) firing structures; and 3) updraft kilns. The latter might be further subdivided as suggested by Arnold. A fourth type, the downdraft kiln, is not encountered in Pharaonic Egypt.

“Among the methods that do not employ a fixed kiln structure is the so-called “open firing,” sometimes referred to as “bonfire firing,” although this latter term implies a rather less orderly arrangement than is usually the case. In open firing the fuel is stacked over (and sometimes among) the vessels. Maximum temperatures reached in an open fire are comparable to those of an unroofed updraft kiln and quite sophisticated results can be obtained. Temperatures of up to c. 1000°C can be reached—the upper range of the firing of pottery referred to as “terracotta” . By its nature an open firing leaves little or no detectable archaeological trace, and any remains that do survive could be mistaken for a large domestic hearth. Indeed, small quantities of pottery may have been fired at the domestic hearth, and it should be remembered that many clays will begin to vitrify at temperatures between 600°C and 800°C.

“Open firing may suffer from lack of control of the firing and from the smudging of the vessels from contact with the fuel; it is furthermore susceptible to sudden changes in weather conditions. Over wide areas of the world this latter problem was countered by firing in trenches, as did the Hopi of North America, or by adding a small wall around the base of the fuel heap, as was done in parts of India. These strategies might be regarded as the simplest kinds of firing structure.”

Types of Kilns and Firing Structures in Ancient Egypt

1st Dynasty pottery jar

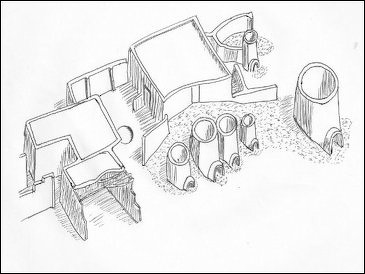

Paul Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: “The arrangement described by Harlan and Hoffman at Hierakonpolis, locality 11C, may represent a development from simple open firing. Dated c. 3200 - 3100 B.C., the structure is a pit in the ground that seems to have contained fuel, while the vessels to be fired stood on “dog-biscuit shaped blocks,” 150 – 250 mm high. The excavators describe this as a simple updraft kiln, because the vessels were raised from the fire on the “dog biscuit” blocks. Although technically correct in that the draft (hot gases) moved upward, it is preferable to regard such arrangements as firing structures to avoid confusion with true updraft kilns. [Source: Paul Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“A further development, and one providing greater protection to the vessels than the arrangement from Hierakonpolis, is the structure known, rather misleadingly, as the “box oven,” a step between open firing and the true updraft kiln. The box oven is essentially a containing wall within which pots are stacked. The fire may be within the wall or, as in the Amarna example described below, outside it and drawn in through an opening at the bottom of the wall. In a true updraft kiln, on the other hand, the fire is located beneath the stack of vessels and is separated from them by a perforated floor. Box ovens are known from at least as early as the Middle Kingdom, at sites such as Mirgissa, and from the New Kingdom at el-Amarna, where an example has been excavated containing its charge of vessels. Holthoer regarded the Mirgissa structure as a bread oven, and it is indeed possible that the same structure served the dual function of breadmold-firing and subsequent bread- baking. It has been shown experimentally that the Amarna kiln/oven could have been used to fire the vessels found within it, and this would certainly have been a more fuel-efficient way of firing the pots than open firing.

“Kilns for the reduction of limestone to lime for use either as mortar or for agriculture are not securely attested from Pharaonic Egypt. James Harrell notes that the use of lime plaster is not certainly recorded before the Ptolemaic era; consequently the occurrence of lime kilns cannot be expected before that date. Lime kilns differ from kilns for firing pottery or faience in that they did not bind material together, but rather reduced it to a friable state. Henein, however, records the use of a combined pottery and lime kiln in Dakhla Oasis, though this appears to be a very localized practice introduced in Islamic times and requiring further study. Because of their specialized nature, lime kilns do not normally feature in accounts of kiln technology.

“The downdraft kiln is not known from Pharaonic Egypt and is mentioned here only in passing. In this type of kiln the hot gases usually pass over a baffle wall of some kind before being drawn down through the stack of vessels and leaving the kiln via a chimney at the rear of the structure, the chimney acting as the means by which the gases are drawn. The firing chamber of such a kiln is enclosed—usually by a dome. The advantage of such a structure is that the heat remains within the kiln longer and there is less chance of discoloration of the vessels as a result of smoke or ash. The downdraft kiln is also capable of reaching temperatures of up to c. 1300°C, whereas the maximum for an uncovered updraft kiln is c. 1000°C. If a dome is added to an updraft kiln, then temperatures of up to c. 1150°C may be achieved, since the dome helps to retain heat as well as reflect it downwards.”

Updraft Kilns Used in Ancient Egypt for Pottery Faience, and Glass

Paul Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: ““True” kilns can be divided into two main types, updraft and downdraft, the distinction between them being whether the hot gases pass upward or downward through the stack of vessels being fired. The updraft kiln is by far the most common historically. In this type of kiln the fire is in the lowermost part of the kiln, known as the fire box or fire pit, and is separated from the vessel stack by a perforated floor or “chequer,” through which the hot gases travel up into the firing chamber where the vessels are stacked. Vessels are commonly inverted in the stack so that each becomes filled with the hot gases, thereby slowing the upward passage of the gases through the structure. This has the effect of increasing the efficiency of the firing, consuming less fuel to achieve the desired result. This is particularly important since it is common for Egyptian updraft kilns to be open at the top, rather than enclosed by a dome. Vessels stacked in such open-topped structures, at least as observed in modern Egypt, are usually given a covering of sherds. The sherd layer acts as a collecting point for soot from the firing, so that the vessels themselves are not blackened by the fuel. It also serves to give a minimal amount of insulation to the stack. The last phase of a firing is often to throw dry vegetation onto the covering of sherds, where it ignites and removes much of the buildup of carbon. [Source: Paul Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“The expansion of vessels tightly packed in a kiln puts considerable stress on the kiln walls, which are usually made of mud-brick that becomes fired brick in situ over time. It is likely that the walls were reinforced in some way, probably by tying large ropes around them in order to prolong their lives. Several tomb scenes show kilns with what appear to be reinforcement bindings around them. This practice of binding the kiln, albeit with iron chains, wire belts, or metal bands rather than ropes, remained common in the European pottery industry into the twentieth century. Such features are clearly demonstrated on the so called “bottle kilns” at Stoke-on-Trent, United Kingdom.

“It is these updraft kilns that are commonly depicted in tomb scenes, particularly from the Middle and New Kingdoms although Old Kingdom examples are known, such as those in the tomb of Ty at Saqqara. Due to the conventions of Egyptian art, it is difficult to determine the scale of these structures, but it is evident from scenes depicting them being unloaded (for example, those at Beni Hasan) that they stood taller than a man and sometimes needed a step or bench at the bottom in order that they could be reached into. Determining the diameter of such structures is more difficult, and there are no known scenes showing a kiln being loaded or unloaded from the inside, as is often the case with present-day Egyptian kilns.

“Fortunately, we are not solely dependent upon depictions of pottery kilns: there are numerous extant examples from Egypt from several periods, including the Old Kingdom at Elephantine and the First Intermediate Period at Ayn Asil (Balat). The excavation at the latter site gives a good impression of the spatial organization of a First Intermediate Period workshop, including tall, tower-like kilns quite wide enough to have accommodated a person during stacking and unloading. The excavators grouped the kilns into several types, largely depending on how the perforated floor, or chequer, was supported. In types 1 through 3 the chequer rested on walls or pillars, while in types 4 and 5 it was supported on projections around the wall, rather than extending onto a support at or near the center of the structure.

Kiln Technology in Ancient Egypt

Paul Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: “All the contemporary Egyptian pottery kilns with which the writer is familiar have the perforated floor springing as a low vault from ground-level projections around the side, as seen in Balat types 4 and 5, or from projections higher up the walls. This arrangement leaves the fire box free of obstruction and makes fueling and raking easier. It is the arrangement that appears to have been used in the several known New Kingdom kilns from el-Amarna. The first of these was discovered by Borchardt (1933), who believed it to be a bread oven. This structure, in house P47.20, was re-excavated in the 1990s and found to be a pottery kiln similar to several others at the site. [Source: Paul Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UK, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Archaeologically, kilns may show evidence of vitrification, since the mud-brick with which they are constructed—often of the same Nile clay as the pots themselves—is fired over and over again. This vitrification is commonly referred to as “slag” by archaeologists as a convenient shorthand, a term that sometimes leads to the belief that the kilns were actually employed for metallurgy (or less correctly glass production, since slag is specific to metallurgy). In fact the substance in question is not true slag and is not encountered in all kilns. Because much Pharaonic pottery is fired at temperatures of 800°C or less it is quite common for the walls of kilns simply to be reddened rather than vitrified. By the same token kiln sites should not be expected to feature “wasters” (overfired vessels): underfiring was almost certainly a more common fault than overfiring.

“One of the reasons for the buildup of so- called slag can be the reaction between the “fly ash” (literally, particles of ash moved up through the structure by the hot gases) and the kiln wall. The silica from ash, along with alkalis contained in it, act to make up the siliceous slag, essentially a layer of glass or glaze on the kiln wall. Fly ash is undesirable, particularly during the firing of vessels with a decorated surface or of glazed wares (such glazed pottery is known in Egypt from Roman times onward).

“One way of obviating the problem of fly ash is to use a downdraft kiln. These were not common in antiquity, however, and the difficulty was more usually solved by the use of “saggars.” Saggars were ceramic containers, stacked one on top of the other, in which pottery whose surface might be damaged by fly ash, or blackened by soot from smoke, was fired. In essence each saggar acted as a miniature, closed kiln. An alternative was to channel the hot gases through vertical pipes between which the vessels were stacked. This arrangement is known from Europe during the Roman Period, and although not yet known from Egypt, it would not be surprising to find it there.

“It is worth repeating here that the top temperature for an uncovered updraft kiln is c. 1000°C. The addition of a dome, which serves to reflect heat back into the structure as well as to contain it, can yield temperatures of 1150°C. Beyond this the Nile silt clay rapidly vitrifies and begins to collapse. Mud-bricks and pottery are essentially of the same material and are thus subject to the same considerations when heated. Where kilns show evidence for a dome, one should consider the possibility that they were glass or metal furnaces rather than pottery kilns, although domed pottery kilns are documented from the ancient world. It has been suggested from the raw materials found in their association that the large kilns or furnaces discovered at el-Amarna, and which show signs of a dome, were intended for the making of glass.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024