Home | Category: Life (Homes, Food and Sex)

FURNITURE IN ANCIENT EGYPT

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “The typical Egyptian house had sparse furnishings by modern standards. Wood was quite scarce, so large furniture items were not common. By far the most common pieces of furniture were small 3 and 4 leg stools and fly catchers. Stools have been found in common houses as well as in Pharaohs’ tombs. Other items of utilitarian furniture include clay ovens, jars, pots, plates, beds, oil lamps, and small boxes or chests for storing things. [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com +]

“The ever present stool was made from wood, and had a padded leather or woven rush seat. The stools’ 3 or 4 legs were very often carved to look like animal legs. Wealthy people had their stools and all furniture in general was richly decorated with gold or silver leaf. The more common people would have things painted to look more expensive than they were. +\

“The Egyptian bed was a rectangular wooden frame with a mat of woven cords. Instead of using pillows, the Egyptians used a crescent-shaped headrest at one end of the bed. Cylindrical clay ovens were found in almost every kitchen, and the food was stored in large wheel-made clay pots and jars. For common people, food was eaten from clay plates, while the rich could afford bronze, silver, or gold plates. The ruling class also commonly had a throne chair with a square back inlaid with ebony and ivory. Almost everyone also had a chest for storing clothing and a small box for jewelry and cosmetics. Walls were painted, and leather wall hangings were also used. Floors were usually decorated with clay tiles.” +\

The Egyptians originally had no tables, at least not of the shape which has come down to us from classical times. Under the Old Kingdom high or low stands of the above shapes were used. These were often made of colored stone. On each was placed a jug or cup, or e. g. , as a preparation for meals, a flat basket which then served as a dinner-plate; a low framework of thin laths was also in use, especially as a stand for jars. These lath-stands in later times constituted the only form of table that was used; in the houses of Tell el Amarna we see them of all sizes in the dining-hall of the master as well as in the bedrooms and kitchens. It is but rarely that we find the old stands for jars and baskets, and then as a rule only in representations of offerings. Instead of cupboards they used large wooden boxes to keep their clothes and such like property. Under the New Kingdom these were generally in the shape of the accompanying illustration with a round cover rising high at the back. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Egyptian Furniture: Design and History” by Fátima Sans Martini (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Furniture Volume I: 4000 – 1300 BC”

by Geoffrey Killen (2017) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Furniture Volume II: Boxes, Chests and Footstools”

by Geoffrey Killen | Mar 31, 2017 Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Woodworking and Furniture” by Geoffrey Killen (2008) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Homes” by Brenda Williams, for older kids, (2002) Amazon.com;

“The Home Life Of The Ancient Egyptians” by Nora E Scott (2006) Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Chairs and Couches in Ancient Egypt

In upper class homes the chairs and couches were often especially handsome; they were often made of ebony inlaid with ivory , and from the earliest period it was customary to shape the feet like the paws of a lion, and if possible to bring in the head of a lion also, as if the king of beasts were offering is a wooden stool covered by a cushion, and carved into the form of a lotus-flower behind, while the legs are shaped like those of a lion. It is intended for one or for two persons, and appears to have been used even down to the time of the New Kingdom. Under the 5th dynasty this seat usually had high sides and a back. These seats are too high and stiff to appear at all comfortable, and in fact under the Middle Kingdom the back was sloped and the sides were lowered. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Under the New Kingdom seats like that seen in the accompanying illustration were in general use. They are as a rule covered with thick downy cushions, and rarely, as in old times, with a simple stuffed leather seat. " Most of them are higher than the corresponding seats of the Old Kingdom, There are many other forms of seats besides these splendid examples, such as stools without backs or lions' paws, made out of palm branches lightly put together; stools made of ebony of careful workmanship; seats which could be folded together like our camp-stools, and low seats for old people, thickly cushioned like our sofas, etc. "

The couch also belongs here. It is really only a broader seat, decorated usually with lions' paws and frequently with a great lion's head. Cushions might be piled up on these couches, as the reader can see in the sleeping apartments in our plan of a house; as a remarkable contrast to the enjoyment of comfort which this suggests we find that a wooden head-rest was used as a pillow at all periods. This was pushed under the neck so that the head hung free over the cushions; the artificial wig of the sleeper thus remained uninjured.

Furniture from Tutankhamun’s Tomb

Over 80 pieces included three adult thrones and one child’s throne. Beds: Nine, mostly intact. Boxes and Cabinets: Many had elaborate painted scenes. Others had inlaid stone and wood veneering. Baskets: About 130 baskets were found. Woven from grasses or palms and lidded, they came in many sizes and held dried foods such as nuts, dates, or seeds. Tools: Knives, flyswatters, and measuring sticks were included.

Tutankhamun's Bed: Several beds were found in the tomb (including one that folded up for travelling). This example is of gilded wood, with an intact base of woven string. A headrest would have been used instead of a pillow, and the rectangular board at one end of the bed is a foot-board (not a head-board as in modern beds). The frame of the bed is supported on feline legs. |::|

Headrest: This elaborate headrest (used instead of a pillow) is made of elephant ivory. When in use, the back of the king's neck would rest on the curved support. The carved figure represents Shu, the god of the atmosphere, and the two lions on the base represent the eastern and western horizons. As well as being a functional object, this headrest has symbolic and ritual meanings too. |::|

See Separate Articles: TUTANKHAMUN’S TOMB: CONTENTS, ITEMS, TREASURES africame.factsanddetails.com

Chairs, Mats and Squatting in Ancient Egypt

Klaus P. Kuhlmann of the German Archaeological Institute in Cairo wrote: “For most people in Africa and the ancient Near East—worldwide, in fact—“squatting” was and is the common position of repose, as it was also for the ancient Egyptians. Amongst ordinary Egyptians, mats (tmA) remained the most commonly used piece of “furniture” for sitting or lying down.’ The ancient Egyptian word for throne is derived from their word for “mat” with the implication being that the Pharaoh on his throne ruled over “the mats,” i.e., his “lowly” subjects . [Source: Klaus P. Kuhlmann, German Archaeological Institute, Cairo, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“ There is evidence, however, that this basic household item originally conferred “status” to its owner, a fact in tune with modern ethnographic data from Africa. Gods are said to be “elevated” on their mats, or the justified dead will be granted the privilege of sitting on “the mat of Osiris”. Archaizing tendencies during the late stages of Egyptian history resulted in the use of the reed mat (= pj wpj, “split,” i.e., reeds) as a word for “throne.”

“Although forcing a posture, which “squatting” people generally experience as being less relaxing, stools and chairs were eagerly adopted by Egypt’s nobility because the raised position signaled “superiority” rather than being a means of achieving more comfort. Ancient Egyptians even attempted to “squat” on a chair. Like a crown or scepter, the chief’s chair became one of ancient Egypt’s most important royal insignia as the quintessential symbol of divine kingship.

Wood and Wood-Like Materials in Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptians suffered from the lack of good wood in the same way as their modern compatriots. It is quite possible that the land was rather better timbered in old times, but the wood produced was always of a very unserviceable nature. Sycamore wood can certainly be cut into great blocks and strong planks; but it is so knotty and yellow that it is quite unsuitable for fine work. The date and dom palm trees only supply long, and as a rule, crooked boards; short pieces of hard wood can be obtained from the tamarisk bushes on the edge of the desert, but the acacia, which furnished a serviceable material for ships, doors, furniture, etc., appears, even in early times, to have been almost extinct in Egypt proper. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

We are not surprised therefore that the Egyptians began at a very ancient date to look about in foreign countries for better wood. Thus the Berlin Museum possesses three great wooden coffins/ belonging to the unknown period between the Old and the Middle Kingdom; they are made of a kind of strong pine-wood which must have been brought to Memphis from the Syrian mountains. This foreign wood must always have been expensive, for native wood was often employed even for ornamental furniture, and was painted light yellow with red veins so as to give the appearance of the costly foreign material. " The native wood was never considered beautiful, and, like limestone and granite, it was almost always covered up with a layer of stucco and brightly painted; the variegated granite alone was allowed to show its natural color.

When agricultural work recommenced after the inundation, the carpenters sallied forth, simultaneously with the ploughmen, to replenish their store of wood. '' As at the present day, flocks of goats went out with them into the fields, to cat the foliage of the trees that were felled. Thus we see that where the axes of the woodcutters have felled a sycamore or a palm goats are always represented browsing on the young leaves of the tree. They have however to pay dearly for this good food; this is a feast day with the woodcutters, and they are allowed to kill a kid. The little creature is hung up on the boughs upon which it had just been feeding, and one of the woodmen cuts it up, whilst his companion boils the water to cook the food they long for so greedily. The meal over, there is still much hard work to be done, the trunk has to be rough-hewn, and afterwards, with a good deal of trouble, carried home hanging on a pole.

Many coffins appear to have been made partly of the cartonage. Cartonage (also spelled cartonnage) is a type of material used mainly in ancient Egyptian funerary masks from the First Intermediate Period to the Roman era. It was made of layers of linen or papyrus covered with plaster. Some of the Fayum mummy portraits were painted on panels made of cartonnage. The pieces of cartonage, which often possess a considerable strength, were probably pressed when wet into the desired shape. Cartonage was similar to papier-mache, so common in the Greek period. It was was prepared from old papyri in the same way papier-mache is made from old paper.

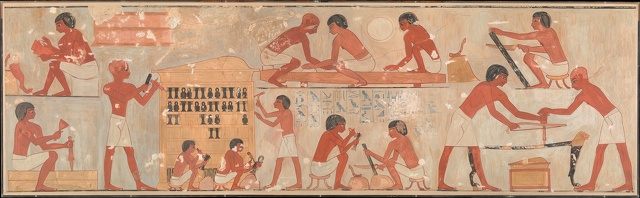

Woodworking in Ancient Egypt

Egyptian carpenters made boats, carriages, portions of houses, furniture, the weapons, coffins, and various kinds of grave goods. When native woods were used, we find a complete lack of planks of any great length; instead objects were made by putting together small planks to form one large one. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

In boat-making, the little boards were fastened the one over the other like the tiles of a roof. In the case of coffins and furniture however, where it was desirable to conceal the joining of the boards, the wood was cut so that the edges should exactly fit together; the adjoining surfaces were then fastened together with little wooden pegs; afterwards the joint was completely hidden by painting. In the same way the Egyptian workmen understood how to make good the holes and bad places in the wood. Wooden pins were commonly used as the method of fastening, and during the periods with which we are occupied, glue was employed but rarely. In the older period they seem to have joined pieces of wood at right angles to each other by the simple miter joint; as far as I know, the so-called dovetailed work came in comparatively speaking much later. '

Wooden furniture, was generally painted; there were other styles of decoration also in use, appropriate to the character of the material in question. Thin pieces of wood, such as were joined together for light seats or were used for weapons, were left with their bark on; they were also sometimes surrounded with thin strips of barks of other colors — a system of ornamentation which has still a very pleasing effect from the shining dark colors of the various barks. A second method was more artistic; a pattern was cut deeply into the wood and then inlaid with wood of another color, with ivory, or with some colored substance. The Egyptians were especially fond of inlaying “ebony with ivory. " This inlaid work is mentioned as early as the Middle Kingdom, and examples belonging to that period also exist. In smaller objects of brown wood, on the other hand, they filled up the carving with a dark green paste.

The Berlin coffins of the time of the Middle Kingdom are excellent ancient specimens of these various styles of workmanship. Images of coffin making show workman bringing strips of linen for cartonage, polishing and painting the coffins, boring holes in the wooden footboards, sawing planks. They also show a leg of a stool cut with an adze. Behind lies the food for the men, close to which a tired-out workman has seated himself.

Tools Used by Ancient Egyptian Woodworkers

The tools used by the carpenters and joiners were of a comparatively simple nature; evidently it is not due to the tools that the work was often carried to such perfection. The metal part of all tools was of bronze, and in the case of chisels and saws was let into the handle, whilst with axes and bill-hooks it sufficed to bind the metal part to the handle with leather straps. For rough-hewing the Egyptians used an axe, the blade of which was about the size of a hand, and was bent forwards in a semicircular form. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Subsequent work was carried on with a tool that, from its constant employment, might almost be called the universal tool of Egypt. This is the adze of our carpenters, a sort of small bill-hook, the wooden part of which was in the form of a pointed angle with unequal shanks; the bronze blade was bound to the short shank and the longer served as a handle. ' To work in the details more perfectly a small chisel was used with a wooden mallet to strike it. "' A large spatulatc instrument served as a plane, with the broad blade of which the workman smoothed off the small inequalities of the wood; '' lastly, a fine polish was attained by continual rubbing with a smooth stone.

adzes and ancient Egyptian carpenter tools

The saw, like our hand-saws, had but one handle, and it was most tedious work to cut the trunk of a thick sycamore into planks with this awkward instrument. As a rule, the wood that had to be sawn was placed perpendicularly and fastened to a post that was stuck into the ground, the part of the wood that was already sawn was tied up, so that its gaping asunder might not interfere with the work. In very early times a stick on which a weight was hung was stuck obliquely through these fastenings; this was evidently intended to keep them at the right tension, and to prevent them from slipping down. For boring, a drill was employed of the shape customary in Egypt even now; the female screw in which it moved was a hollow nut from the dom palm. '"

Nearly all these tools enumerated from tomb-pictures, have been found at archaeological sites. A basket was found, probably in one of the Theban temples, containing the tools employed by King Thutmose III in the foundation ceremonies for a temple. We see that they are tools specially prepared for this ceremony, for they are not suitable for hard work; they give us however a variety of model specimens, from which we can form a very good idea of the simpler tools used by the Egyptian workman.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024