Home | Category: Life (Homes, Food and Sex)

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN BREAD

Bread was the staple of the ancient Egyptian diet, and most of it was made with barley or emmer wheat, a twin-kerneled form of grain that is very difficult to husk. Hieroglyphics have recorded 14 types of bread, including sourdough and whole wheat breads. Scholars speculate that families usually ate unleavened pita-style bread at home and ate pot-baked breads during temple festivals and special occasions. [Source: David Roberts, National Geographic, January 1995]

In a report published in the journal Science in 1996, Dr. Delwen Samuel, a research associate in archeology at Cambridge, described his examination with optical and electron microscopes of nearly 70 loaves of bread found among the ruins of workers' villages. Almost all of the bread was made from a type of wheat known as emmer, sometimes flavored with coriander and fig.

There is little evidence that Egyptians used modern-style wheat to make bread. Modern bread is high in gluten, which makes it light, full of air holes, and with a crispy crust. Barley and emmer wheat are low in gluten and bread made with these grains tends to heavy and dense. Wild yeast native to the areas bread was produced made the bread rise. The Egyptians were not familiar with yeast and they believe that bread rose by way of "miraculous powers. To get their bread to rise they let their dough stand for a week or so, so that it fermented like wine as well as rose.

The Egyptians made toast but they did not do it to improve the flavor or texture but to remove moisture that attracted mold. Making toast preserved the bread longer.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Egyptian Food and Drink” by Hilary Wilson (2008) Amazon.com;

“Food Fit for Pharaohs: An Ancient Egyptian Cookbook”

by Michelle Berriedale-Johnson (2008) Amazon.com;

“The Pharaoh's Kitchen: Recipes from Ancient Egypt's Enduring Food Traditions”

by Magda Mehdawy (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptians’ Diet: The History of Eating and Drinking in Egypt by Charles River Editors (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Diet Reconstruction: The Elemental Analysis of Qubbet el Hawa Cemetery Bones” by Ghada Al-Khafif (2016) Amazon.com;

“Famine and Feast in Ancient Egypt” by Ellen Morris (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: Food and Festivals” by Stewart Ross (2001) Amazon.com;

Nile Style: Egyptian Cuisine and Culture: Ancient Festivals, Significant Ceremonies, and Modern Celebrations” by Amy Riolo (2009) Amazon.com;

“Wine & Wine Offering In The Religion Of Ancient Egypt” by Mu-chou Poo (2013) Amazon.com;

“Wine in Ancient Egypt: A Cultural and Analytical Survey” by Maria Rose Guasch Jane (2008) Amazon.com;

“Red Land, Black Land: Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Barbara Mertz Amazon.com;

“Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs” by A. G. McDowell (1999) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

Making Bread in the Ancient World — A Terrible Job

Candida Moss wrote in Daily Beast: “Baking can be hard work: it takes time, elbow grease, and patience. But the effort lockdown-bakers expend in kneading is nothing in comparison to the processing that turns grain into flour. Working a mill was one of the most feared and laborious tasks in the ancient world. It was a punishment for rebellious enslaved workers and a mere step up from the death-sentence of working in the mines. New archeological evidence shows that mill workers and miners may have even worked together to select materials and ease their burden. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, October 3, 2021, 6:00 PM

“Small hand-mills — which were used by domestic bakers in antiquity as well — aren’t too cumbersome and they are a step up from a mortar and pestle. But the larger hourglass and rotary mills used in Roman bakeries involved physical strength and were often powered by donkeys and “chained convicts” (as Pliny noted in his Naturalis Historia). The hourglass mills, which can still be seen in the bakeries at Pompeii, were comprised of a solid bell-shaped stone over which a hollow hourglass shaped stone was placed. The hourglass stone both functioned like a hopper that fed grain into the mill and was also turned around the base stone to grind the grain. The worker (human or donkey) would circle the mill turning the hourglass stone as he walked.

Making Bread in Ancient Egypt

A bakery found near the Pyramids of Giza was 17 feet long and eight feet wide. The bread was often made in molds or pottery bread pots that produced loaves in many shapes and sizes — round, flat, conical and pointed. Most bread appears to have been made on flat trays, or in bell-shaped pots (14 inches in diameter and 14 inches deep). Archaeologists also found egg-carton-like trenches. The holes held bread-baking pots and the trenches held coals that were used to bake the bread. [Source: David Roberts, National Geographic, January 1995]

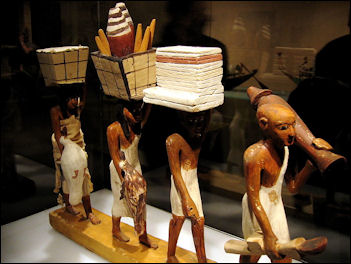

carrying bread and other things The most common type of bread was made by first pouring thin cake-batter-like dough into a thick clay pot about the size of a large vase. After the dough had risen the pot was placed in a hole dug in the embers of a fire. A second pot was heated and placed on top of the first pot, and together the two pots created an "oven environment. A small sculpture from ancient Egypt shows a man rolling dough on his hands and knees.

Based on modern experiments scientists determined the bread was baked for around an hour and 40 minutes and a cone-shaped loaf of bread was removed by running a knife along the inside of the pot. The bread was heavy and as nutritious as modern store-bought bread. One of the scientist who participated in making bread described it as "sourdough bread the way it's meant to taste."

Describing the result of his effort to make bread the ancient Egyptian way, archaeologist Mark Lehner told National Geographic: "We did produce edible bread from various combinations of barely and emmer, albeit a bit too sour even for most sourdough tastes because we let he dough sit too long before baking. Each of our loaves was heavy and massive, large enough to feed several people at one meal.

Grinding the Grain for Bread in Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptians grinded up grain on granite grind stones. Among the objects unearthed at Umm Mawagir (“mother of bread molds,” in Arabic) — a settlement that flourished in Egypt’s western desert more than 3,500 years ago — was a double bread mold, one of a half-ton of bakery artifacts. The study of ancient bread has been made possible because it was the practice of ancient Egyptians to leave food and beer in their tombs for sustenance in the afterlife and the arid climate preserved those remains.

It seems that ancient Egyptians, in the older periods anyway, didn’t have mills; we never find one represented in their tombs. On the contrary, in the time of the Middle as well as of the New Kingdom we find representations of great mortars in which one or two men arc “pounding the corn “with heavy pestles, just in the same way as is done now in many parts of Africa. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

They obtained finer flour however by rubbing the grain between two stones. The lower larger stone was fixed and sloped towards the front, so that the prepared flour ran into a little hollow in the front of the stone. Under the Old Kingdom the stone was placed on the ground and the woman who was working it had to kneel before it; under the Middle Kingdom a table hollowed out in front took the place of the lower stone, the woman could then stand, and her work was thus rendered much lighter.

Kneading the Dough and Cooking the Bread in Ancient Egypt

After preparing the grain the next thing to be done in the making of bread was the kneading of the dough, which could be done in different ways. Shepherds, in the fields at night, baking their cakes in the ashes, contented themselves with “beating the dough “in an earthen bowl and lightly baking their round flat cakes over the coals of the hearth or in the hot ashes only. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Little sticks served as forks for these hungry people to take them out of the glowing embers, but before they could eat them they had first to brush off the ashes with a wisp. It was otherwise of course in a gentleman's house. ' Here the dough was placed in a basket and kneaded carefully with the hands; the water was pressed out into a pot placed underneath the basket.

In the picture of the court-bakery of Ramses III" the dough here is not kneaded by hand — this would be too wearisome a method when dealing with the great quantitics required for the royal household — it is trodden with the feet. Two servants are engaged in this hard work; they tread the dough in a great tub holding on by long sticks to enable them to jump with more strength. Others bring the prepared dough in jars to the table where the baker is working.

Cooking Different Types of Ancient Egyptian Bread

The dough was fashioned by the hand into various shapes similar to those we now use for pastry, and these were baked on the conical stove. I purposely say on the stove, for the Egyptians seem to have been satisfied with sticking the cakes on the outside of the stove. A picture of the time of the New Kingdom gives us a tolerable idea of one of these stoves; it is a blunted cone of Nile mud, open at the top and perhaps three feet high. The fire is burning in the inside, the flames burst out at the top, and the cakes arc stuck on the outside.

In the images of court-bakery of Ramses III, the court baker he is not content with the usual shapes used for bread, but makes his cakes in all manner of forms. Some are of a spiral shape like the “snails “of our confectioners; others are colored dark brown or red, perhaps in imitation of pieces of roast meat. There is also a cake in the shape of a cow lying down. The different cakes are then prepared in various ways — the “snails “and the cow are fried by the royal cook in a great frying pan; the little cakes are baked on the stove.

The ancient Egyptians baked in heated ceramic pots. Ancient grains are more difficult to bake with, because they contain very little gluten, Seamus Blackley, an amateur Egyptologist and one of the inventors of the Xbox game console, told the BBC. Blackley has a passion for baking and said that the ancient-Egyptian-style bread they created had “a nice structure and a cake-like crumb — very soft. ” The bread had a caramel aroma — sweeter than a modern sourdough. [Source: Alix Kroeger BBC, August 7, 2019]

Ancient Bakery Found in Egyptian Desert

In 2010, 3,500-year-old bakery was discovered an ancient Egyptian settlement, rough a half-kilometer long, at the El-Kharga Oasis by Theban Desert Road Survey, a project to map ancient desert routes in the Western desert, a team of Egyptian and US archaeologists from Yale University led by John Coleman Darnell. Making bread on a massive scale was the main occupation for the majority of the inhabitants, said Zahi Hawass, the head of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities. [Source: Rossella Lorenzi, Discovery News, August 25, 2010]

Rossella Lorenzi wrote in Discovery News: “The archaeologists unearthed two ovens and a potter’s wheel. This was used to make the ceramic bread molds in which the bread was baked. The large debris dumps outside the bakery suggests that the settlement produced bread in such large quantities that it may have even been feeding an army, Hawass said in a statement.

Making Bread Today from Ancient Egyptian Yeast

Marley Brown wrote in Archaeology magazine: Nothing lives forever — except maybe yeast, which can go dormant and hibernate, perhaps indefinitely. An archaeologist, a biologist, and a baking enthusiast have recently embarked on a collaborative project to revive and reuse millennia-old yeast. They believe they have succeeded in identifying, isolating, and even baking bread with strains of yeast that may have been used by Middle Kingdom Egyptians to make bread — and brew beer — more than 4,000 years ago. [Source:Marley Brown, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2019]

“Archaeologist Serena Love of the University of Queensland is interested in brewing beer using Egyptian recipes, which scholars have attempted to piece together by studying tomb paintings and analyzing the microstructure of starch preserved in the archaeological record. Love, along with tech inventor and dedicated baker Seamus Blackley, set out to acquire ancient yeast strains that have secure archaeological provenance. They contacted museums across the United States and beyond, requesting to access their collections and extract yeast from Egyptian ceramics, stressing that the vessels would not be damaged. Eventually, they were given permission to work with artifacts housed at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and Harvard University’s Peabody Museum.

bakery

“To help devise a noninvasive method of collecting the yeast while minimizing contamination, the team recruited University of Iowa biologist Richard Bowman. He, too, is interested in re-creating ancient beers and has developed a yeast-extraction method — still being refined — that aims to preserve the condition of antiquities while avoiding surface contaminants. Foremost among these threats is airborne wild yeast, which, like all manner of fungi and bacteria, is all around us. Bowman’s method involves using a needle-less syringe filled with liquid containing yeast extract, dextrose, and amino acids to moisten a cotton ball that has been placed on the surface of the artifact. “We continue soaking that particular area of the vessel until it is completely saturated and the cotton ball stops drying out,” Bowman explains. After waiting five to 10 minutes for the liquid to penetrate the pores of the ceramic and “wake up” the yeast, the process is reversed. The syringe sucks the liquid back up through the same cotton ball and, finally, any harvested yeast is isolated and incubated.

Bowman says that it may never be possible to completely eliminate the risk of contamination, and admits that the strains the team has thus far worked with may belong to ambient yeast floating around the museums. He was heartened to discover, however, that while the ostensibly ancient yeast did not take well to being grown in a modern lab, it responded immediately to conditions under which it would have grown in antiquity. “When Seamus put the yeast in emmer flour, which is what they would have been eating in ancient Egypt,” Bowman says, “it immediately proliferated. ”

“Love is now attempting to gain access to a broader range of artifacts from various periods and regions of ancient Egypt. She hopes to investigate differences in yeast used to brew the dozen or so varieties of beer that ancient Egyptians are thought to have produced. The team also plans to send out strains of yeast for genome sequencing. “We can determine the yeast’s subspecies,” explains Bowman, “and by consulting a database of genetic information collected on yeast, we can then compare the strain to its descendants. ” This should allow the team to create a model of gene transformation over time that will help estimate how old the extracted yeast is. For his part, Blackley says the bread made from the (most likely) ancient yeast was like nothing he’s ever tried. “I was a little concerned about its texture,” he says. “But when it came out of the oven, I could smell that it was going to be fantastic. ”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024