Home | Category: Art and Architecture

CRAFTS IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Tutankhamun treasure The Egyptians developed fairly sophisticated chemistry through cosmetic-making, dying, glassmaking and gold metallurgy. Pottery making was well advanced by 3000 B.C. The earliest Egyptian pottery was unglazed red earthenware. Both Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt had the pottery wheel by that time. The potter's wheel is believed to have been invented in Mesopotamia around 3500 B.C. and may be tied to the invention of wheeled vehicles. See Mesopotamia.

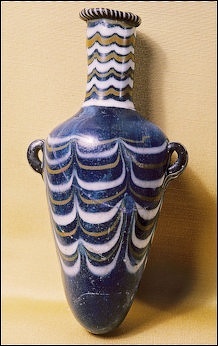

Ceramic objects could be decorative, used in daily life or have religious significance. Bottles, jars and jugs used to carrying things and for storage were often made of fired clay. Decorative pottery was sometimes covered with a blue glaze. Many types of ornamental pottery were made for royalty and aristocrats. Even beads and jewelry were made of clay.

The ancient Egyptians also created a wide variety of things from Egyptian alabaster (not a true alabaster but a form of calcite), including vases used in libation rituals, monkey headed jars used to hold mummified organs. Some were ground so thin you could see through them. Craftsman also made flint knifes inscribed with hieroglyphics, terra-cotta figures and jars, bowls and platters carved from diorite and porphyry. Black-topped vessels dated to 3500 B.C. has been found in Hierakonpolis are among the finest pottery Egypt ever produced.

On an exhibit of art related to Queen Hatshepsut Peter Schjeldahl, the art critic for The New Yorker, wrote, “Some of the loveliest and most absorbing pieces in the show are among the smallest. Two tiny items...a red carnelian amulet in the bovine form of Hathor (the goddess of love and beauty) and a white glass bead. They are inscribe with praise of the Pharaoh and, on the case of the amulet...Other objects — little boxes and baskets, charming vases in human and animal form, a chair with original caning intact."

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Treasures of Ancient Egypt” by Nigel Fletcher-Jones (2019) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: An Image Archive for Artists and Designers” by Kale James (2025) Amazon.com;

“Beni Hassan: Art and Daily Life in an Egyptian Province” by Naguib Kanawati and Alexandra Woods (2011) Amazon.com;

Tutankhamun's Trumpet: Ancient Egypt in 100 Objects from the Boy-King's Tomb

by Toby Wilkinson (2022) Amazon.com;

“King Tutankhamun: The Treasures of the Tomb” by Zahi Hawass (2007) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun, His Tomb and Its Treasures”, lots of images, by I. E. S. Edwards (1976) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Jewelry: 50 Masterpieces of Art and Design” by Nigel Fletcher-Jones (2020) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Jewelry” by Carol Andrews (1991) Amazon.com;

“Nubian Gold: Ancient Jewelry from Sudan and Egypt” by Peter Lacovara and Yvonne J. Markowitz (2019) Amazon.com

“Jewels of Ancient Nubia” by Yvonne Markowitz, Denise Doxey (2014) Amazon.com;

“The Origins and Use of the Potter’s Wheel in Ancient Egypt” by Sarah Doherty (2015) Amazon.com;

”A Manual of Egyptian Pottery, Volume 1: Fayum A - A Lower Egyptian Culture”

by Anna Wodzinska (2011) Amazon.com;

“Stone and Metal Vases” by W.M. Flinders Petrie (1853-1942) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Art” Multilingual Edition by Salima Ikram (2018) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Ancient Egypt: Revised Edition” by Gay Robins (2008) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Art” by Rose-Marie Hagen, Rainer Hagen, Norbert Wolf (2018) Amazon.com;

“Reading Egyptian Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Egyptian Painting and Sculpture”

by Richard H. Wilkinson (1994) Amazon.com;

“Principles of Egyptian Art” by H. Schafer and John Baines (1986) Amazon.com;

“Highlights of the Egyptian Museum” by Zahi Hawass (2011) Amazon.com;

“Hidden Treasures of Ancient Egypt: Unearthing the Masterpieces of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo” by Zahi Hawass (National Geographic, 2004) Amazon.com;

“Eternal Egypt: Masterworks of Ancient Art from the British Museum”

by Edna R. Russmann (2001) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt At The Louvre” by Guillemette & Marie-Helene Rutschowscaya & Christiane Ziegler (trans Lisa Davidson). Andreu (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Egypt and the Ancient Near East”

by New York The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Peter F Dorman, et al. (1988) Amazon.com;

Craftsmen in Ancient Egypt

The low esteem in which uper class Egyptians held their farmers extended also to their craftsmen. According to the learned opinion of the scribes, the latter were also poor creatures who led an inglorious existence, half pitiable and half ridiculous. Thus a poet of the Middle Kingdom speaks, for example, of the metalworker: “I have never seen the smith as an ambassador, Or the goldsmith carry tidings; Yet 1 have seen the smith at his work At the mouth of his furnace, His fingers were hkc crocodile (hide), He stank more than the roe of fish. " The same scribe also thus describes the work of a wood-carver: "Each artist who works with the chisel Tires himself more than he who hoes (a field). The wood is his field, of metal are his tools. In the night — is he free? He works more than his arms are able. In the night — he lights a light." [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Fortunately we are not dependent on these gloomy sources to form our opinion of Egyptian handicrafts, for the work of the metalworkers and woodcarvers which still exists shows that these industries reached a very high standard in Egypt, a comparatively far higher one in point of fact than either learning or literature. The workmen who created those marvels of gold and ivory, of porcelain and wood, the finish of which we admire to this day, cannot have been such wretched creatures as they were considered by the proud learned professors.

In some cases, craftsmen achieved relatively high status. Anne Austin wrote in the Washington Post: “The village of Deir el-Medina was built for the workmen who made the royal tombs during the New Kingdom (1550 to 1070 B.C.). During this period, kings were buried in the Valley of the Kings in a series of rock-cut tombs...The village was built close enough to the royal tomb to ensure that workers could hike there on a weekly basis. These workmen... were highly skilled craftsmen.” They were given a variety of amenities afforded only to those with the craftsmanship and knowledge necessary to work on something as important as the royal tomb. The village was allotted extra support: The Egyptian state paid them monthly wages in the form of grain and provided them with housing and servants to assist with tasks such as washing laundry, grinding grain and porting water. Their families lived with them in the village, and wives and children could also benefit from these provisions from the state.” [Source: Anne Austin, Washington Post, February 17 2015. Anne Austin is a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University ***]

Khonsu’s Tomb: What It Says About the Artisan’s Life

Catharine H. Roehrig of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Almost thirty-three centuries ago, a young man named Khonsu became a "servant in the Place of Truth"—a designation that identified members of the crew of artisans who carved and decorated the royal tombs of the New Kingdom. These artisans included quarrymen, scribes, draftsmen, sculptors, painters, and carpenters. The entire crew, which usually numbered no more than sixty, lived with their families in a walled community known to its residents simply as the Village, a ruin now known as Deir el-Medina. Situated in a small desert valley on the west bank of the Nile, at the edge of the Theban cliffs, the Village was within easy reach of the two principal royal cemeteries: the Great Place, now called the Valley of the Kings; and the Place of Beauty, or the Valley of the Queens. [Source: Catharine H. Roehrig Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“Khonsu was the fourth son in a large family, and like most members of the royal work crew, he and at least one of his brothers had followed in the footsteps of their father, Sennedjem, who was also a servant in the Place of Truth. Sennedjem was an active member of the crew in the time of Menmaatre Seti, the son of a former general named Ramesses who had ascended the throne of Egypt and founded a new dynasty. \^/

“Sennedjem and his sons were fortunate to live during a period of great prosperity for the Village. At the height of Sennedjem's career, in the first sixteen years of the new dynasty, two royal tombs were required. The amount of time it took the crew to complete a royal tomb depended on the length of a king's reign, and work was sometimes cut short by the pharaoh's death. Because of the length of time required for mummification, the team would have up to three months to finish its work, and then the process would begin all over again for the new pharaoh. \^/

Tutankhamun Anubi “The same talents that created a spectacular sepulchre for the ruling king were also put to use in the more modest burial places of the workers themselves. Located in a terraced cemetery on the hillside adjacent to the Village, their funerary monuments included small, vaulted, above-ground offering chapels that were topped by miniature, steep-sided pyramids. In or near the chapels, shafts cut deep into the bedrock led to groupings of corridors and vaulted rooms that were often used by many generations of the same family. One of the finest of these tombs belonged to Sennedjem and his descendants. Built at the southern end of the cemetery, the family crypt was just a stone's throw away from its owner's house. The upper level of the complex had offering chapels for both Sennedjem and Khonsu, and the decorated burial chamber contained the mummies of Sennedjem and his wife, Iineferti; Khonsu and his wife, Tameket; Khonsu's younger brother Ramesses; and four other named members of the family, as well as eleven unidentified mummies. \^/

“In preparation for his journey to the afterworld, Khonsu commissioned a pair of nesting anthropoid coffins made of wood. The lid of each depicts Khonsu in the form of a mummy, with arms crossed over his chest and hands clutching the tyet amulet and djed pillar, the same magical symbols that were used some 200 years earlier on Hatnofer's chair to ensure the owner's well-being. The coffins are covered with magical texts and vignettes featuring deities as well as Khonsu and Tameket. A mask of painted wood and cartonnage completed the ensemble. Khonsu had also obtained a painted canopic box to hold his internal organs and several shawabtis, little figurines that were intended to substitute for the deceased owner if he were called upon to perform any kind of manual labor in the next life. \^/

“When he finally began his own journey to the afterworld, Khonsu was about sixty-five years of age and had seen two generations of his descendants enter the work crew. He was placed in the family tomb along with his parents, and the funeral rites were probably performed by his sons Nakhemmut and Nakhtmin, who spoke the words of the offering texts and repeated the names of those who had passed on to the next world, thus giving them renewed life. After being used by many generations of Khonsu's descendants, the family crypt was sealed at last and remained undisturbed until February 1, 1886, when it was uncovered by agents of the Egyptian Antiquities Service.”

Objects Taken by Ancient Egyptians to the Afterlife

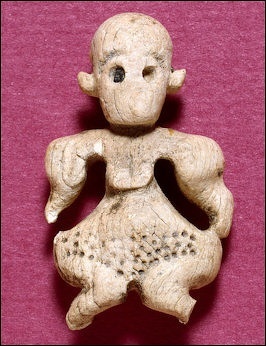

figure of a female dwarf

Ken Johnson wrote in New York Times that the ancient Egyptians believed that life “was only a prologue to the main attraction, the afterlife, and they devoted much of their tremendous creative and technological ingenuity to ensuring that their dead — the wealthy ones, anyway — would have everything needed on the next plane of existence. They pickled the bodies of the deceased, stocked their graves and tombs with food, drink, jewelry, furniture, pets, reading material and whatever else that might come in handy upon awakening in the next dimension.” [Source: Ken Johnson, New York Times, March 11, 2010]

In 2010, the Brooklyn Museum hosted an exhibition called “To Live Forever: Art and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt,” which focused on objects for the afterlife and explored all facets of the Egyptian funerary industry. Organized by Edward Bleiberg, the museum’s curator of Egyptian art, the exhibition presented more than 100 objects, from massive stone sarcophagus covers and elaborately decorated wooden coffins to statuettes and elegant ink drawings on sheets of papyrus.

“One of the exhibition’s least prepossessing objects,” Johnson wrote, “is a terra-cotta sarcophagus lid molded rather crudely into a cartoonish, bust-length portrait of a man. Made sometime between 1292 and 1075 B.C., it is like the work of an untrained folk artist imitating the kind of deluxe Egyptian artistry that museums have made more familiar. It is included to demonstrate that the quality of a coffin depended on what the family could afford. Just like today, in ancient Egypt professional coffin makers offered a range of options priced according to the cost of material and labor. Clay, painted to resemble royal sarcophagi, was the material of choice for budget-minded customers.

Another revealing piece, and a more beautiful one, is an 8 ½-inch-tall figure of a man smoothly carved in lustrous dark wood, from about 1400 to 1336 B.C. It is a particularly lovely example of a shabty, a magical servant that would do chores for the deceased in the afterlife. Rich people had many shabties made of precious materials, including wood, which was a rare commodity. The less fortunate had to settle for shabties made of faience, a glazed earthenware. According to the Brooklyn Museum catalog while the wealthy might have a different shabty for every day of the year, “40 shabties were an ideal number to own in the Ramesside Period” because that provided “enough workers for each of the 30 days of the month plus overseers and foremen.”

Faience pieces did not necessarily look cheap, however, so rich as well as poor had shabties made from it. Among the exhibition’s most striking objects is a weird jade-green faience sculpture less than three inches high representing a dwarf standing with each foot on the head of an alligator and each hand gripping a snake by the neck. Identified as Pataikos or a form of the dwarf-god Bes, this little fellow was put into a tomb to protect the dead.

Ancient Egyptian Art Objects

Tutankhamun Ankh-Mirror Egyptians liked jewelry. They wore necklaces with blue faience beads, and gold leaf; girdles of cowrie shells molded in gold; silver bracelets with semi-precious stones; golden amulets decorated with the face of Hathor, the Egyptian goddess of love and fertility; and pencil thick glass-stud earrings. Some jewelry was believed to be imbued with magical powers. Glass eyes bead were worn perhaps to ward off evil.

Jewelry was made from gold, silver, faience (a blue stone), lapis lazuli, carnelian, green feldspar, green jasper, ivory, bone, amethyst, and black quartz. Silver was regarded as more valuable than gold. Tombs were filled with jewelry the dead wanted to take with them to the netherworld. Tomb paintings and reliefs are also full depictions of people loaded down with jewelry.

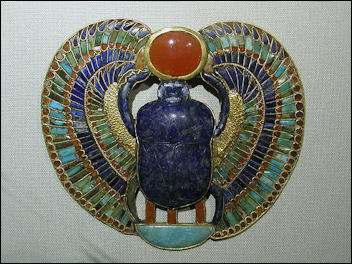

Amulets were carried by the living and wrapped with mummies. The mummy of King Tut had 143 of them. Their primary purpose was to attract “sympathetic magic” that would protect the wearer from misfortune and maybe bring some good luck. Amulets were inserted in different stages of the embalming process, each with special spells and incantations to go along with it. Some bore inscriptions and were made of materials, such as gold, faience (a blue stone), lapis lazuli, carnelian, green feldspar, and green jasper.

Amulets with protective cobras, “ ba” (winged symbols of the soul), “ re” (sun disk), ankhs, and scarabs were popular. There were amulets for limbs, organs and other body parts and ones derived from the hieroglyphics for “good,” “truth,” and “eternity.” Hearts, hands and feet were often found on mummies in places where the real body parts were normally found, the idea being that they could be offered as substitutes if the real ones were coveted by demons.

In Genesis 41:41-42 a pharaoh gives Joseph a ring to symbolize a deal has been made. Most ancient rings were made of steatite of medals such as bronze, silver or gold. Few were adorned with precious stones. Those that were usually contained amethyst, coral or lapis lazuli. Some of the oldest known rings were used as signets by rulers, public officials and traders to authorize documents with a stamp. Signatures were not used until late in history. Describing an enamel seal Blake Gopnik wrote in the Washington Post: “The shiny bug itself, molded from glassy paste, is as bright and colorful as a real beetle’s carapace and immaculately carved to evoke the thing of nature...It exemplifies the perfect balance among the striking realism, an economy of formal means and a lust for eye-filling splendor.”

Objects in the Egyptian Museum

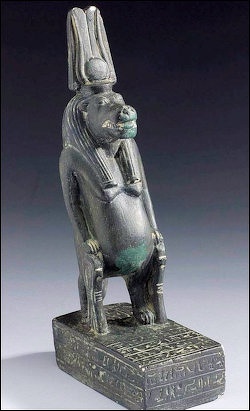

cult statue of taweret

The bottom Floor of the Egyptian Museum displays items in chronological order beginning with Old Kingdom to the left as you enter the museum and continuing through the Middle and New Kingdoms as you circle the perimeter of the museum and finish with Ptolemaic and Greco-Roman pieces on the right side of the entrance. Here you can see artworks, statues, sarcophagus, treasures and other items that are connected with specific pharaohs or have a historical connection. Particularly interesting are the statues of Queen Hatshepsut, the only woman to become a pharaoh. She is often depicted as a man with a false beard.

On the opposite side of the museum from the entrance is a section devoted to the pharaoh Akhenaten, who promoted monotheism. There are large statues of the unusual-faced Pharaoh. Artifacts from Ramses's reign include a beautiful gold bracelet with a pair of lapis lazuli ducks; and a scene of Ramses holding the hair and chopping of the heads of Libyan, Syrian and Nubian warriors. His wooden coffin bears his likeness and the crook and flail, symbols of power and the god of the afterlife. To give the dead something to look at, under the lid of coffin is a picture of his son Merneptah and Nut, the gods of the star-filled sky.

One of the oldest artifacts discovered from ancient Egypt is a triangular two-foot-high slate carving showing King Narmer, wearing the crown of Upper Egypt, grasping the hair and humiliating an enemy from Lower Egypt to unify the nation. The carving, dated to 3100 B.C., also shows the falcon God Horus, symbolizing victory looking on. The other side shows him wearing the crown of Lower Egypt, leading a victory parade. King Narmer founded ancient Pharonic Egypt by uniting Lower (northern) Egypt and Upper (southern) Egypt in 3200 B.C.

One of the museums greatest treasures is the splendid tomb of Prince Rahotep and his wife Nofret. This extraordinary 4,500-year-old artifact is presided over by painted life-size figures representing the royal couple. The white-skinned princess is wearing a red-and-blue necklace and headband with floral designs. Her fleshtone shirtless husband has a blue mustache. Both figures have been inlaid with quartz.

Other interesting pieces include a diorite statue of King Khafa (builder of the second largest pyramid at Giza); the unfinished head of Queen Neferteri; wooden statues scribes; the 4000-year-old hammered copper statues of the flat-headed, obsidian-eyed Pepi I; the schist statue of the pharaoh Mankaure, with a woman, mostly likely his wife Khamerernebty, putting an arm around his waist.

The Top Floor of the Egyptian Museum mostly displays treasures and artifacts according to theme. There are separate rooms for tools, everyday objects, painted clay models, religious objects, clothes and shoes, painted papyrus scrolls, animal mummies, jars for holding the organs of mummies, jewelry and small wooden statues. The King Tutankhamen Collection occupies about a forth of the top floor. There is also a large display of mummy cases and sarcophagi. One of the highlights is the display of mummy cases from Fayum and Harawa that have beautiful portraits of the dead , with three-dimensional shading, on the faces and panels of the mummy cases.

Among the items on display on the top floor are medicines and make-up cases; small statues of hippos, mongooses and hedgehogs; an obsidian-eyed golden bust of Horus; and papyrus scrolls of women and a crocodile sharing a drink in the waters of paradise. A papyrus scroll dating back to 1100 B.C. shows a gowned mouse-queen being taken care of by a retinue of cats. One cat is cuddling a mouse baby while two others are grooming the queen, who is sitting on a stool drinking some wine from what looks like a martini glass.

King Tutankhamen Collection

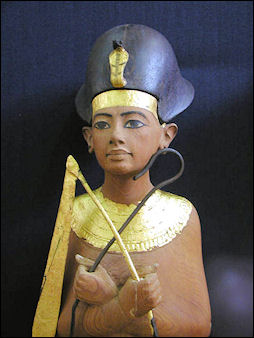

Tutankhamun Eye of Horus pendant The King Tutankhamen Collection (on the top floor of the Egyptian Museum) contains nearly 5,000 objects. Among them are the famous blue-and-gold funerary mask. The mask is made of beaten gold. The beard on the masks identifies the king as being one with Osiris, god of the dead, and the cobra and vulture on his forehead symbolize the Upper and Lower kingdoms of Egypt. A life-size statue of the king, which was found at the entrance of the tomb, is dressed in gilded clothing and was anointed in black resin to denote rebirth.

The mummy was enclosed in a coffin, a sarcophagus and four decorated and gilded wooden shrines — one inside the other. The shrines had images of the king emblazoned on the them. The largest, outer golden shrine is 9 feet high, 10¾ feet wide and 16½ feet long. It is inlaid with panels of brilliant blue faience with depictions of special symbols that protected the dead. The innermost one was covered in gold. The sarcophagus is made of yellow quartzite and has a sculpted goddess spreading protecting arms and wings over the feet area. Each shrine and the sarcophagus is displayed separately.

King Tutankhamun’s polished gold coffin weighs 250 pounds and is inlaid with precious and semi-precious stones. On the lid is a low relief golden effigy of the king. The figure holds a crook and flail, both of which symbolize the king's power. Guarding the coffin during ancient times was the goddess Selket, who was so powerful, it was said, she could cure the string of the scorpion which she wears on a crown on her head. During the Six Day War the coffin was stored in a secret bomb proof shelter.

King Tutankhamun’s tomb is regarded as the the richest royal collection every found. When the king’s coffin was opened, 143 amulets and pieces of jewelry were found tucked in the linen layers of the mummy. Also in the collection is a 15.3 inch coffin for the pharaoh's liver. Only the heart remained in the body when it was mummified. Another coffin contained his viscera.

Many of big items were found in the anteroom outside the burial chamber. These include gold couches, four gold chariots, a golden throne, alabaster vases and scores of personal items of the king — all of which are on display. The king’s wooden throne is covered in sheets of gold, silver, gems and glass and is decorated with an intimate scene of the queen rubbing Tutankhamun with perfumed oil.

Tutankhamun’s clothes chest is decorated with a scene showing the king shooting his bow and arrow from a chariot while galloping at full speed, trampling Nubians under the wheels of his chariot. Tutankhamun was buried with six chariots, 50 bows, two swords, two daggers, eight shields and assorted boomerangs and slingshots. An inscription of the chest reads "hundreds of thousands of Nubians bowed to him during the battle."

There is also a beautiful painted effigy; a feminized alabaster bust; a walking stick adorned with carvings of Arabs and Nubians; a boat with an ibex bowhead and a nude maiden captain; and statue of Anubis, the jackal god of the necropolis, whose job it was to discourage intruders. So that he may gaze upon himself and procreate in the afterlife the king was buried with a mirror shaped like an ankh, the symbol of life, and pieces of jewelry adorned with scarabs, the symbols of fertility.

Tutankhamun throne

King Tutankhamun was also was buried with ordinary things likes boards games, a bronze razor, cases of food and wine, and linen undergarments. Among the small items are gold daggers for protection in the afterlife; a headrest for rebirth; and an alabaster cup which proclaims "Mayst thou spend millions of years...sitting with thy face to the north wind...beholding felicity." There are also effigies of gods and goddesses, jeweled daggers, earrings, necklaces, 2,000 amulets and pieces of jewelry, gold figures, a leopard skin mantel decorated with gold stars, a child's chair made of ebony and ivory, 15 gold and jeweled rings, seeds, boat paddles, ear and neck ornaments, 50 ornamental vases, robes, sandals, arrows, bows, boomerangs, a forked stick for caching snakes and a lock of hair from Queen Tiye, Tutankhamen's mother.

Weaving in Ancient Egypt

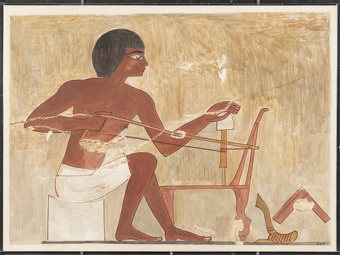

The Egyptians were skilled weavers. Many inscriptions extol the garments of the gods and the bandages for the dead. The preparation of clothes was considered as a rule to be woman's work, for truly the great goddesses Isis and Ncphthys had spun, woven, and bleached clothes for their brother and husband Osiris. During the Old Kingdom this work fell to the household slaves, in later times to the wives of the peasant serfs belonging to the great departments. In both cases it was the house of silver to which the finished work had to be delivered, and a picture of the time of the Old Kingdom shows us the treasury officials packing the linen in low wooden boxes, which are long enough for the pieces not to be folded. Each box contains but one sort of woven material, and is provided below with poles on which it is carried by two masters of the treasury into the house of silver. In other cases we find, as Herodotus wonderingly describes, men working at the loom; and indeed on the funerary stelae of the 20th dynasty at Abydos, we twice meet with men who call themselves weavers and follow this calling as their profession. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The operation of weaving was a very simple one during the Middle Kingdom. The warp of the texture was stretched horizontally between the two beams, which were fastened to pegs on the floor, so that the weaver had to squat on the ground. Two bars pushed in between the threads of the warp served to keep them apart; the woof-thread was passed through and pressed down firmly by means of a bent piece of wood. " A picture of the time of the New Kingdom however gives an upright loom with a perpendicular frame. The lower beam appears to be fastened, but the upper one hangs only by a loop, in order to facilitate the stretching of the warp. We also see little rods which are used to separate the threads of the warp; one of these [ certainly serves for a shuttle. A larger rod that runs through loops along the side beams of the frame appears to serve to fix the woof-thread, like the reed of our looms.

See Separate Article: WEAVING IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Woodworking in Ancient Egypt

vessel with a feather pattern

Egyptian carpenters made boats, carriages, portions of houses, furniture, the weapons, coffins, and various kinds of grave goods. When native woods were used, we find a complete lack of planks of any great length; instead objects were made by putting together small planks to form one large one. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Wooden furniture, was generally painted; there were other styles of decoration also in use, appropriate to the character of the material in question. Thin pieces of wood, such as were joined together for light seats or were used for weapons, were left with their bark on; they were also sometimes surrounded with thin strips of barks of other colors — a system of ornamentation which has still a very pleasing effect from the shining dark colors of the various barks. A second method was more artistic; a pattern was cut deeply into the wood and then inlaid with wood of another color, with ivory, or with some colored substance. The Egyptians were especially fond of inlaying “ebony with ivory. " This inlaid work is mentioned as early as the Middle Kingdom, and examples belonging to that period also exist. In smaller objects of brown wood, on the other hand, they filled up the carving with a dark green paste.

The Berlin coffins of the time of the Middle Kingdom are excellent ancient specimens of these various styles of workmanship. Images of coffin making show workman bringing strips of linen for cartonage, polishing and painting the coffins, boring holes in the wooden footboards, sawing planks. They also show a leg of a stool cut with an adze. Behind lies the food for the men, close to which a tired-out workman has seated himself.

See Separate Article: FURNITURE AND WOODWORKING IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Feathers and Ostrich Eggs in Ancient Egypt

Emily Teeter of the University of Chicago wrote: “Throughout Egyptian history, feathers appear in purely utilitarian settings and also in ritual contexts where they ornament crowns and personify deities. Feathered fans were used to signal the presence of royal or divine beings, and feathers identified certain ethnic types. Feathers are known from representations and also actual examples recovered primarily from tombs. [Source: Emily Teeter, University of Chicago, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2010, escholarship.org ]

“Feathers appear frequently in ancient Egyptian iconography, they are are referred to in texts, and they are incorporated into hieroglyphic writing. The prestige and value of feathers is attested by New Kingdom tomb paintings that show foreign delegations from Nubia, Libya, Asia, and Punt laden with exotic merchandise, including feathers. Most commonly shown are what appear to be the wing and tail feathers of ostriches and the wing feathers of falcons; however, it is often difficult to associate the representations with specific species of birds. Feathers were obtained by felling birds with bow and arrow and throw stick, by trapping birds with nets, and through trade.

Jacke S. Phillips of the School for Oriental and African Studies in London wrote: “Ostriches were hunted in what are now the southern Egyptian, Sudanese, and Libyan deserts for food, feathers, and eggshells from the earliest times. From their eggshells beads, pendants, and vessels were manufactured. Decorated eggshells were used from the Predynastic Period onward and seem to have a religious meaning. [Source: Jacke S. Phillips, School for Oriental and African Studies, London, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

See Separate Article: POSSESSIONS AND EVERYDAY ITEMS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Egyptian Pottery and Ceramics

Tutanhkamun Shabti Pottery making was well advanced by 3000 B.C. The earliest Egyptian pottery was unglazed red earthenware. Both Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt had the pottery wheel by that time. The potter’s wheel is believed to have been invented in Mesopotamia around 3500 B.C. and may be tied to the invention of wheeled vehicles. See Mesopotamia.

The Egyptians developed fairly sophisticated chemistry through cosmetic-making, dying, glassmaking and gold and iron metallurgy. Ceramic objects could be decorative, used in daily life or have religious significance. Bottles, jars and jugs used to carrying things and for storage were often made of fired clay. Decorative pottery was sometimes covered with a blue glaze. Many types of ornamental pottery were made for royalty and aristocrats. Even beads and jewelry were made of clay.

Paul T. Nicholson of the University of Wales wrote: “Pottery is usually the most common artifact on any post- Mesolithic site. In Egypt its abundance can fairly be described as overwhelming, and it generally requires substantial resources in order to be properly recorded by excavators. Pottery was the near- universal container of the ancient world and served those purposes for which we might now use plastics, metal, glass and, of course, modern ceramics. Its abundance in the archaeological record is not due merely to its wide use, but to its near indestructibility, and this is in turn a facet of its technology. [Source: Paul T. Nicholson, University of Wales, Cardiff, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

See Separate Article: ANCIENT EGYPTIAN POTTERY AND CERAMICS africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024