Home | Category: Education, Health and Transportation

TYPES OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN BOATS

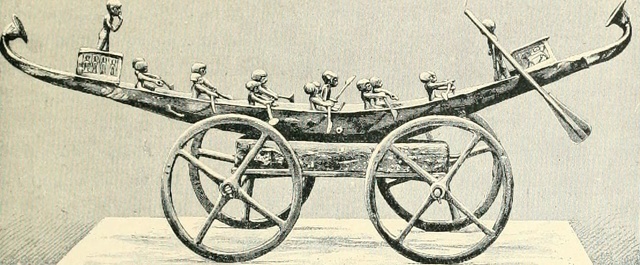

Egyptian barque Steve Vinson of the University of Indiana wrote: “A large variety of boat types can be identified in ancient Egypt, ranging from small papyrus rafts that might be capable of carrying only a single person, up to extremely large vessels used for transporting exceptionally large cargoes like obelisks (see especially the obelisk barge of Hatshepsut pictured at Deir el-Bahri, which was 120 cubits, or about 60 meters, long). [Source: Steve Vinson, University of Indiana, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

Vessels can also be divided into ceremonial/official vessels and working vessels. Ceremonial/official vessels often had the “wjA” profile of a divine bark: that is, a long, narrow hull with a bent stern decoration and an upright bow post, best exemplified by the 4th Dynasty Khufu vessel. These decorative posts were intended to evoke the tied-off ends of papyrus rafts, evoking Egyptian mythology in which the vessels of the gods appear as papyrus. Actual working vessels, on the other hand, while adopting a great many sizes and proportions, were typically broader than ceremonial vessels, generally lacked purely decorative posts, and typically had greater free-board (that is, the distance from the surface of the water to the deck).

“Prior to the introduction of the sail, probably in the very late Predynastic Period, pictorial evidence suggests that paddling (i.e., with the paddle held in the paddler’s hand, not mounted on, or attached to, the vessel in any way as an oar would be) was the principal method of vessel locomotion, although there is evidence for towing as well. With the introduction of the sail, nearly any vessel of any size would appear to have been equipped with mast and sail. However, ceremonial vessels or military vessels, or vessels like the personal “yachts” of dignitaries, for which demonstration of wealth and power, as well as speed and reliability of service were critical, continued to employ large crews of paddlers or rowers. Vessels primarily intended for cargo transportation, on the other hand, appear to have had comparatively smaller crews and to have relied as far as possible on wind power or towing.

Pictures during the Old Kingdom represent several different sorts of boats. Inscriptions do not speak of boats simply, but of “square-boats, stern-boats, tow-boats," etc. The large row-boats had flat stern and bow; the cabin however takes up nearly the whole length of the vessel. These boats do not seem to be intended for sailing — in fact there would be no room for a mast on account of the size of the cabin.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SHIPS AND BOATS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

RIVER TRANSPORT AND USES OF BOATS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SEA TRAVEL IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MERER'S DIARY: 4,600-YEAR-OLD LOGBOOK ABOUT PYRAMID BOATMEN africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Egyptian Boats and Ships” by Steve Vinson (2008) Amazon.com;

“A Categorisation and Examination of Egyptian Ships and Boats from the Rise of the Old to the End of the Middle Kingdoms by Michael Allen Stephens (2012) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Boats and Ships” by Sean McGrail (2008) Amazon.com;

“Boats” (Egyptian Bookshelf) by Dilwyn Jones (1995) Amazon.com;

“Ship 17 a Baris from Thonis-Heracleion” (Ships and boats of the Canopic Region in Egypt) by Alexander Belov (2018) Amazon.com;

“J3: a ship's boat from the Portus Magnus, Alexandria” by Damian Robinson and Franck Goddio (2025) Amazon.com;

“The Gurob Ship-Cart Model and Its Mediterranean Context: An Archaeological Find and Its Mediterranean Context” by Shelley Wachsmann, Alexis Catsambis, et al. Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Watercraft Models from the Predynastic to Third Intermediate Periods”

by Ann Merriman (2011) Amazon.com;

“Pharaoh's Boat” by David Weitzman Amazon.com;

“How to Build Egyptian Boat Models: Patterns and Instructions for Three Royal Vessels” by Jack Sintich (2012) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The World of Ancient Egypt: A Daily Life Encyclopedia" by Peter Lacovara, director of the Ancient Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage Fund (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2016) Amazon.com

Terminology for Ancient Egyptian Boats

“As one might expect, the Egyptians had a large variety of terms for various types of river or ocean-going craft, which can rarely be directly identified with a specific type known to us from the iconographic record. Possibly the most common word was dpt, an old term that occurs in both the Pyramid Texts and the Palermo Stone and seems to have been a common word for almost any type of boat or even ship; the term designates large, sixteen-framed vessels constructed by Sneferu in the 4th Dynasty and the large Red Sea ship in the Middle Kingdom Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor (e.g., Shipwrecked Sailor 25). One interesting and also very old term is the dwA-tAwy, or “Praise of the Two Lands” vessel, a term that may have been used to designate large, ceremonial vessels similar to the Khufu funerary vessel from the Early Dynastic Period onward.

“Other descriptive terms include terms based on the numbers eight, ten, and sixteen, which may have been intended to convey a general notion of the size of a craft, based on the number of internal frames (ribs) the vessel had. The term aHa, or “that which stands up,” was common from the Middle Kingdom forward and may be a metonym—i.e., a term designating a mast that comes to represent the vessel itself. In the New Kingdom, a common term for a cargo vessel was the wsx, or “broad” vessel.

Some New Kingdom vessel designation may be of foreign origin, particularly the very common br, which seems to have originally designated vessels used on the Mediterranean and Red Sea. This name continued to be common into the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods and was rendered by Greek authors beginning with Herodotus as “baris.” For Greek authors, a baris appears to have been a common working Nile boat, and the Demotic word byr, which underlies the Greek form, also appears most often in this sense. However, the word appears to designate sea-going ships in the Demotic text of the Rosetta Stone inscription and also appears once in a Demotic docket to a Persian Period Aramaic document, there designating what appears to be a ceremonial vessel.

Ancient Egyptian Papyrus Boats

Early boats were made of papyrus reeds which grow in abundance in the Nile and were also used to make paper-like materials and a host of other things. Papyrus river crafts had a narrow beam and a high, elegantly tapered stem and stern posts featured ends made from raised and bound papyrus. The slender shape was well suited from navigating river currents. Wooden boats that came later had a similar design.

making a papyrus boats in ancient Egypt; from a Wall fragment from the Sun Temple of Nyuserre Ini at Abu Gurob, 2430 BC

One of the earliest representations of a papyrus boat is a clay vessel from the Naqada culture dated to 3500 B.C.. The vessel had two cabins and 40 oars. A similar vessel was depicted on a small ivory plaque from 3100 B.C. The hulls of papyrus boats were much more fragile than the hulls of wooden boats. Bipedal and A-frame masts are thought to have been used; they distributed weight over the hull.

The oldest little barks made of papyrus reed used in Egypt can still be found on the Nile in the Sudan. These boats had no deck, they were in fact little rafts formed of bundles of reeds bound together. They were rather broader in the middle than at the ends, the hinder part was generally raised up high whilst the front part lay fiat on the water. The smaller of these boats, in which there was scarcely room for two people, consisted of one length only of papyrus reed; the larger (some were even big enough to carry an ox) were formed of several lengths cleverly put together. In the building of these boats," every endeavor was made of course to join the reeds firmly together; a threefold rope was fastened round them at distances of about nine inches. When a boat of this kind was intended for the master's use, a thick mat was spread over the floor as a protection from the damp. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Even during the Old Kingdom boats were built of large dimensions and of considerable port — thus we hear of a “broad ship of acacia wood, 60 cubits long and 30 cubits broad," such as nearly 100 feet long and 50 feet across, and a boat of this immense size was put together in 17 days only. The number of various forms of boats in the pictures of the Old Kingdom shows how highly developed was this branch of handicraft.

Uses of Paprus Boats

Small papyrus crafts were widely used to ferry two or three people at a time across canals. They were also use on the marshes for hunting and fishing. Papyrus boats drew very little water, and were therefore were easy to use by hunters and fishermen in the shallow waters of the marshes. They were easy to guide on account of their lightness and their small size; and even where the water was too shallow, they could be carried without any difficulty to deeper water. These little skiffs never had sails, nor were they ever rowed properly; they were either propelled along with poles provided with two points to catch the bottom, or by short oars with broad blades, with which the rower lightly struck the surface of the water; the latter could be used equally well standing or squatting. This primitive style of rowing, which is still in use amongst some of our river fishermen, sufficed very well for the little papyrus barks, especially as they only carried light weights; a touch was enough to send them gliding over the smooth water.

Papyrus boats were occasionally built of larger dimensions, thus, e. g., in the time of the 6th dynasty we find one which required at least thirty-two rowers and a steersman. This was a foolish innovation and did not last long; as a rule, the larger boats, even in early ages, were all built of wood, though, as we have seen in the preceding chapter, Egypt was very badly off for that material. Under the pressure of necessity however the Egyptians used their bad material to great advantage; and it seems that, even in very early times, boat-building was carried on most extensively.

The papyrus reed boats are similar to the reed boats used on Lake Titicaca in Peru and Bolivia. Thor Heyerdahl, of Kon Tiki fame, believed that the Incas in Peru were descendants of ancient Egyptians. Thor Heyerdahl’s Ra II expedition attempted to show that the ancient Egyptians may have arrived in the America’s thousands of years before Columbus. The reed boats he used were similar to boats depicted on wall paintings from ancient Egypt and are used today on Lake Titicaca in Peru and Bolivia.

Sail Boats in Ancient Egypt

There is no doubt that the best and quickest craft during the Old Kingdom were the long flat sailing-boats used by men of rank for their journeys. '"' They were built of a light yellow wood, doubtless a foreign pine wood. As we see, they differ from the other boats in that the fore and hind parts are shorter and lower than is otherwise customary; these are also frequently thrown into relief by decoration; they may be painted dark blue, or the prow may end in the carved head of an animal; this head is always turned backwards, contrary to the direction of the figure-heads in our modern ships. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

On the black wooden deck behind the mast stands the cabin, the sides of which consist of prettily plaited matting, or of white linen, that can be wholly or partly taken down. During the journey the cabin is the home of the master, for even if he holds the rank of an admiral he takes no part of course in the management of the boat. We have not yet mentioned the pilot, who, with a pole in his hand to sound the depth, stands in the bows and gives directions to the steersmen.

When they approach the bank in order to disembark the pilot has to call to the men who are to help with the landing, and as he has to do this when at some distance from shore, we find that (even as early as the 4th dynasty) a speaking trumpet was used for this purpose. The sailor squatting behind on the roof of the cabin has a responsible position; he looks after the sail, and with quick gestures repeats the commands of the pilot. In addition to the sail, these vessels almost always carry oars, generally about a dozen on either side. The number of rudder-oars to steer the vessel varies according to the number of oars — to nine oars on a side there belong two rudder-oars; to fourteen, three; to twenty-one, four.

Cargo Boats in Ancient Egypt

Space for people on board the larger transport vessels was restricted; all the room was utilised for stowage, so that the space allotted to the rowers and steersmen was insufficient and uncomfortable. The outer edge was high, so as to give more ship space, while in the middle of the vessel stood the large main cabin, and just behind it a second cabin, the roof of which sloped downwards to the stern. Nevertheless, it was not enough that thus four-fifths of the length of the vessel should be taken up with the cabins, even the remaining fifth was not left for the rowers, but had to serve as space for the cattle for transport. The three or four men, therefore, who rowed a freight vessel of this kind, had to balance themselves on a balustrade erected in the stern, whilst the two steersmen had to manage their rudder-oars from the sloping roof of the stern cabin. Besides the freight vessels proper, there were special small boats that were used for carrying lesser weights; these could be rowed and steered at the same time by one man, and might, for instance, accompany the large sailing boat of a gentleman and his suite as provision boats. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

When sailing was impossible owing to contrary winds, or, as is too often the case on the Nile, when a dead calm ensued, the sailors had to resort to the tedious work of towing, owing to the strong current. " In the pictures of the vessels therefore, even of the Old Kingdom, we see that most of them have a strong post round which the tow-rope can be twisted. In traveling by boat the Egyptians of old times were so accustomed to this wearisome expedient that they could not even imagine that their gods could do without it, and according to their belief the bark of the sun-god had nightly to be towed through the netherworld; it was only by day it could go forwards on the ocean of the sky by means of its sails and oars.

Vessels that were intended to carry a large freight seem to have been always towed either by men or by other vessels; they were too heavy for independent movement. We must here mention the boat called the Sa, the name of which probably signifies tow-boat. Neither the prow nor the poop was specially characteristic, except that at both ends there was a short perpendicular post for the tow-line. They were steered, like all vessels of the Old Kingdom, by means of long oars. This kind of vessel was employed in the transport of blocks from the quarries on the eastern bank to the pyramids and tombs of the Memphite necropolis. The vessel represented here, which is expressly stated to be unusually large, belonged to King Isi of the 5th dynasty, and bore the name of “Fame of Isi. " In our picture she is laden with the sarcophagus and the sarcophagus cover, which the king presented as a gift to his faithful servant, the chief judge.

Fishing Boats

Fish were caught in the Nile and the Mediterranean. Reliefs show fishermen using nets and harpoons to catch fish in shallow water. At the Temple of Hatshepsut there is a scene of birds being captured in nets. Agricultural crops were not the mainstay of the ancient Egyptian diet. Rather, the Nile supplied a constant influx of fish which were cultivated year around.”[Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

Steve Vinson of the University of Indiana wrote: “Pictorial evidence shows that fishing boats were generally small, able to be operated by one to five persons. Vessels might be rafts made of papyrus bundles (e.g., as seen in the papyrus models Y from the Middle Kingdom tomb of Mekhet-Ra) or made of wood (excellent illustration in the Ramesside tomb of Ipy). Many illustrations of fishing from boats show fishermen using various types of nets, sometimes (as in the two Mekhet-Ra papyrus boat models) with two craft working together. [Source: Steve Vinson, University of Indiana, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

Other methods used from boats or rafts were spearing and line-fishing. Depictions of fishing are especially common in the Old Kingdom, but can be found in the Middle and New Kingdoms as well; documentary evidence for commercial fishing continues on into the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, when there is at least some evidence for women involved in the occupation.”

Sea-Worthy Ships in Ancient Egypt

The first known vessels that could handle the waves of the Mediterranean were boats that had stiffer hulls that appeared around 2400 B.C. These vessels didn't have a keel but were kept from tipping over by suspension-bridge-like rope trusses that were attached to upright supports that ran from the bow to stern. The ships were propelled forward by oars and a tall sail mounted on a bipedal mast.

Records dating to the time the Pyramids were built describe vessels traveling to Lebanon to pick up cedar and other valuable woods. An entry on the Palermo Stone, an early record of ancient events, describes an expedition of 40 vessels picking up enough logs to construct 170-foot-long ships. Egyptian ships plied the Red Sea and traveled as far as Punt (near modern-day Somalia) there is an account of one expedition returning with 80,000 measures of myrrh, 6,000 units of electrum (an alloy of gold and silver), 2,600 units of wood, and 23,020 measures of unguent.”

Around 1500 B.C. Egyptians learned how to make keels and internally reinforced hulls. Sails were rigged differently and steering oars were relocated. Around this time two new kinds of ships emerged: sailing ships with wider hulls and smaller crews used for transporting goods and long, narrow oar-driven galleys that were developed for warfare.

Sailing ships transported cargo like wine and olive oil in five- to ten-gallon amphorae (ceramic jugs). Several vessels of this type and their cargos have found by archaeologists. A boat used by Queen Hatshepsut to carry obelisks to Karnak was larger and broader than Admiral Nelson’s “Victory”. The ancient Egyptian vessel was 200 feet long and 70 feet in beam.

Funeral of a Mummy by Arthur Bridgeman

Luxury Boats in Ancient Egypt

The tendency to luxury, which is so characteristic of all the later epochs of Egyptian history, naturally had its effect on the adornment of their vessels. During the Old Kingdom the vessel used by the princes in traveling was a simple narrow boat, adorned with the head of a ram at the bows; during the New Kingdom, on the other hand, the vessel of a man of rank had to be decorated in the most sumptuous manner. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The cabin has become a stately house with a delightful roof and an entrance adorned with pillars; the sides of the vessel gleam with the brightest colors, and are adorned in the fore part with large paintings; the stern resembles a gigantic lotus flower; the blade of the rudder-oar resembles a bouquet of flowers, whilst the knob at the top is fashioned into the head of a king; the sails (of the temple-barks at any rate) consist of the richest cloth of the most brilliant colors.

A good example of the extent to which luxury was carried in this particular, during the New Kingdom, is seen in the royal vessel of Thutmose III. This vessel bears the very same name as it bore during the Old Kingdom — "Star of the two countries"; it is therefore nominally the same royal vessel as carried King Khufu fifteen centuries before,'' but how different is its appearance compared with the ancient simplicity. The cabin is now a building with a front door and tapestried walls of gay colors; the boardings for the helmsman and the captain resemble chapels, and near the latter there stands, as figure-head, the statue of a wild bull trampling men underfoot, evidently in allusion to the “victorious bull," such as the king.

This luxury only extended, as I need scarcely observe, to the vessels used for traveling by rich people. The transport vessels during the New Kingdom remained as unadorned as before. They were furnished with a rough latticed partition on the deck for the cattle or for other freight.

Ceremonial Barks of Ancient Egypt

Steve Vinson of the University of Indiana wrote: “It has been long argued whether the Khufu vessels were “solar” barks—that is, intended to identify the king with the sun god Ra in the next world—or whether they were his own ceremonial vessels, buried with him as a ritual offering. In fact, these possibilities need not have been mutually exclusive, and we have no reason to suppose that the vessels could not have been understood to serve multiple functions in varying contexts. [Source: Steve Vinson, University of Indiana, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“Even more important than the ceremonial barks of kings were those of gods. Portable boat models were central to many cultic practices, and the holy-of-holies of Egyptian temples were often bark-shrines, places where these cultic models would be placed between symbolic voyages within or outside of the divinity’s home temple. However, some gods, notably the state god Amun in the New Kingdom, possessed full-scale river boats. The bark Amun-User-Hat, or “Amun-Mighty-of- Prow,” is known from multiple New Kingdom sources, both textual and iconographic. Perhaps most famously, the bark figures in the terminal New Kingdom/early Third Intermediate Period Tale of Wenamun, which recounts the experiences of a (fictional) priest dispatched to Lebanon to purchase cedar for a renovation of the bark. A second important sacred vessel was the Neshmet bark of Osiris, which appears to have been involved in a water-borne ritual drama at Abydos, in which boats manned by “confederates of Seth” attempted—always unsuccessfully—to attack and murder Osiris.

“Large-scale ceremonial barks continued in use in major Egyptian temples well into the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods. Herodotus described boats used in the Persian Period during rites connected with Osiris. From the Ptolemaic Period, the Apis Embalming Ritual describes a procession of the deceased Apis to the “Lake of Kings” near the Memphite Sarapeion. Following this procession, the cadaver of the Apis was laid out on the lake’s shore, while priests standing on a papyrus bark recited the appropriate ritual texts. These procedures were intended to suggest both the Osirian and solar aspects of the Apis bull and his impending metempsychosis and rebirth. A fascinating late Roman Demotic graffito from the Temple of Philae records the graffitist’s donation of a large amount of pitch for the purpose of water-proofing the sacred bark of Isis.

See Separate Article: FUNERAL FOR AN EGYPTIAN PHAROAH africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024