Home | Category: Education, Health and Transportation

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN BOATS

.jpg) The ancient Egyptians used vessels powered by sails, oars and both. Their boats lacked rudders and instead were steered with a pair of stern mounted oars. Egypt was crisscrossed by canals and boats of various sizes were use on the Nile, the canals and the sea. The oldest crafts were built from papyrus. Later wooden boats became the norm. Large yachts were used to move people up and down the river. Cargo ships plied the Nile and the sea. The most elaborate vessels were buried with pharaohs for their journey to the afterlife and were perhaps never used as real boats.

The ancient Egyptians used vessels powered by sails, oars and both. Their boats lacked rudders and instead were steered with a pair of stern mounted oars. Egypt was crisscrossed by canals and boats of various sizes were use on the Nile, the canals and the sea. The oldest crafts were built from papyrus. Later wooden boats became the norm. Large yachts were used to move people up and down the river. Cargo ships plied the Nile and the sea. The most elaborate vessels were buried with pharaohs for their journey to the afterlife and were perhaps never used as real boats.

Steve Vinson of the University of Indiana wrote: “Ancient Egyptian boats are defined as river-going vessels (in contrast with sea-going ships). Their use from late Prehistory through the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods included general transportation and travel, military use, religious/ceremonial use, and fishing. Depending on size and function, boats were built from papyrus or wood. The oldest form of propulsion was paddling, although there is some evidence for towing as well. Sailing was probably introduced towards the end of the late-Predynastic Period. [Source:Steve Vinson, University of Indiana, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

In ancient times, boats were expressions of technology in its most advanced form. A vase painting of a reed boat with a pole mast and a square sail indicated that the Egyptians had been using sailing vessels as early as 3500 B.C. Most early Egyptian boats were built for going up and down the Nile. They were not strong enough to handle traveling in the open sea. The oldest known boat is a dugout found in Denmark dated to 6000 B.C. Scientists believe some kind of boat was used by ancient people to reach Australia at least 50,000 years ago.

RELATED ARTICLES:

TYPES OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN BOATS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

RIVER TRANSPORT AND USES OF BOATS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SEA TRAVEL IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MERER'S DIARY: 4,600-YEAR-OLD LOGBOOK ABOUT PYRAMID BOATMEN africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Egyptian Boats and Ships” by Steve Vinson (2008) Amazon.com;

“A Categorisation and Examination of Egyptian Ships and Boats from the Rise of the Old to the End of the Middle Kingdoms by Michael Allen Stephens (2012) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Boats and Ships” by Sean McGrail (2008) Amazon.com;

“Boats” (Egyptian Bookshelf) by Dilwyn Jones (1995) Amazon.com;

“Ship 17 a Baris from Thonis-Heracleion” (Ships and boats of the Canopic Region in Egypt) by Alexander Belov (2018) Amazon.com;

“J3: a ship's boat from the Portus Magnus, Alexandria” by Damian Robinson and Franck Goddio (2025) Amazon.com;

“The Gurob Ship-Cart Model and Its Mediterranean Context: An Archaeological Find and Its Mediterranean Context” by Shelley Wachsmann, Alexis Catsambis, et al. Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Watercraft Models from the Predynastic to Third Intermediate Periods”

by Ann Merriman (2011) Amazon.com;

“Pharaoh's Boat” by David Weitzman Amazon.com;

“How to Build Egyptian Boat Models: Patterns and Instructions for Three Royal Vessels” by Jack Sintich (2012) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The World of Ancient Egypt: A Daily Life Encyclopedia" by Peter Lacovara, director of the Ancient Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage Fund (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2016) Amazon.com

Importance of Boats in Ancient Egypt

“Boats in ancient Egypt were ubiquitous and crucially important to many aspects of Egyptian economic, political, and religious/ideological life. Four main categories of uses can be discussed: basic travel/transportation, military, religious-cere-monial, and fishing. Examples of each can be traced from the formative period of Egyptian history down to the close of Egypt’s traditional culture in the fourth century CE. One terminological problem is to identify a dividing line between “boats” and “ships.” For the purpose of this article, the term “ship” is arbitrarily taken to mean craft working entirely or primarily at sea (i.e., on the Red Sea or Mediterranean). Therefore, we confine ourselves here as far as possible to water craft of any size that were intended primarily for service on the Nile.”

The sun god, ancient Egyptian believed, used two boats to travel through the heavens: one for day and one for night. Pharaohs were buried with two boats to assist them in their journey to the afterlife. The pharaohs, when they were living , enjoyed hunting waterbirds and hippopotamus from boats and no doubt hoped to continue the hobby in the afterlife. Hunting scene with boats are featured in many Egyptian tombs.

Discovery of an Ancient Egyptian Boat That Fits Herodotus's Description

Egyptian barque In the 5th century B.C, the Greek historian Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “The boats in which they carry cargo are made of the acacia, which is most like the lotus of Cyrene in form, and its sap is gum. Of this tree they cut logs of four feet long and lay them like courses of bricks,42 and build the boat by fastening these four foot logs to long and close-set stakes; and having done so, they set crossbeams athwart and on the logs. They use no ribs. They caulk the seams within with byblus. There is one rudder, passing through a hole in the boat's keel. The mast is of acacia-wood and the sails of byblus. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

These boats cannot move upstream unless a brisk breeze continues; they are towed from the bank; but downstream they are managed thus: they have a raft made of tamarisk wood, fastened together with matting of reeds, and a pierced stone of about two talents' weight; the raft is let go to float down ahead of the boat, connected to it by a rope, and the stone is connected by a rope to the after part of the boat. So, driven by the current, the raft floats swiftly and tows the “baris” (which is the name of these boats,) and the stone dragging behind on the river bottom keeps the boat's course straight. There are many of these boats; some are of many thousand talents' burden. 97.

In 2020, Benjamin Leonard wrote in Archaeology magazine: “For the first time, researchers working in a ship graveyard in the ancient Egyptian port city of Thonis-Heracleion have identified a vessel precisely matching the firsthand description given by Herodotus of a common type of Egyptian cargo ship known as a baris. “It’s a very rare case when a written source and archaeological material make such a perfect match,” says archaeologist Alexander Belov of the Russian Academy of Sciences. The short, thick planks of local acacia wood that form the hull of what is known as Ship 17 are arranged in the staggered, brick-like pattern described by Herodotus, and its keel contains a shaft that the historian notes held a rudder. Dozens of other similar barides that remain submerged at the site appear to have been discarded after years of transporting goods on the Nile, Belov explains. Ship 17, which was sunk before the mid-fourth century B.C. and pinned to the seabed with wooden poles, seems to have been used to increase the length of a nearby pier. [Source: Benjamin Leonard, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2020]

Ancient Egyptian Papyrus Boats

Early boats were made of papyrus reeds which grow in abundance in the Nile and were also used to make paper-like materials and a host of other things. Papyrus river crafts had a narrow beam and a high, elegantly tapered stem and stern posts featured ends made from raised and bound papyrus. The slender shape was well suited from navigating river currents. Wooden boats that came later had a similar design.

making a papyrus boats in ancient Egypt; from a Wall fragment from the Sun Temple of Nyuserre Ini at Abu Gurob, 2430 BC

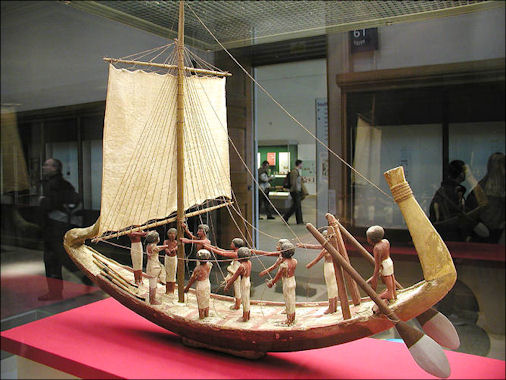

One of the earliest representations of a papyrus boat is a clay vessel from the Naqada culture dated to 3500 B.C.. The vessel had two cabins and 40 oars. A similar vessel was depicted on a small ivory plaque from 3100 B.C. The hulls of papyrus boats were much more fragile than the hulls of wooden boats. Bipedal and A-frame masts are thought to have been used; they distributed weight over the hull.

The oldest little barks made of papyrus reed used in Egypt can still be found on the Nile in the Sudan. These boats had no deck, they were in fact little rafts formed of bundles of reeds bound together. They were rather broader in the middle than at the ends, the hinder part was generally raised up high whilst the front part lay fiat on the water. The smaller of these boats, in which there was scarcely room for two people, consisted of one length only of papyrus reed; the larger (some were even big enough to carry an ox) were formed of several lengths cleverly put together. In the building of these boats," every endeavor was made of course to join the reeds firmly together; a threefold rope was fastened round them at distances of about nine inches. When a boat of this kind was intended for the master's use, a thick mat was spread over the floor as a protection from the damp. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Even during the Old Kingdom boats were built of large dimensions and of considerable port — thus we hear of a “broad ship of acacia wood, 60 cubits long and 30 cubits broad," such as nearly 100 feet long and 50 feet across, and a boat of this immense size was put together in 17 days only. The number of various forms of boats in the pictures of the Old Kingdom shows how highly developed was this branch of handicraft.

Structure of Ancient Egyptian Boats

The characteristic form of a Nile boat, in which the hinderpart rises high out of the water, is also seen in the boats of the Old Kingdom; it was doubtless due to practical reasons. In the first place, in the small boats and papyrus skiffs, which were not rowed but rather pushed along, this hindcrpart gave the man who propelled them a good hold; a more important matter on the other hand was that it enabled the boat to be easily pushed off from the many sandbanks, on which even the boats of the present day are continually stranded. The channel of this sacred stream was constantly changing; even large boats were therefore built with very little draught, so that as a rule they only skimmed the water, scarcely a third of their length touching the surface; we must except the transport boats, which drew more water and were therefore built unusually flat. A boat about 50 feet long would have sides scarcely 3 feet high, and had not another plank been laid along the edge, the water would certainly have beaten into the boat. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

During the Old Kingdom the oars ' belonging to the wooden boats had sometimes a very narrow pointed blade; they were used quite in the modern fashion, and not like those of the papyrus skiffs. The oars were put into rowlocks or through the edge of the boat; the rowers sat facing the stern and pulled through the resisting water. To prevent the oars from being lost, each was fastened to the boat by a short rope, and when the oar was not being used, it was drawn out of the water and made fast to the edge of the boat.

The rudder was unknown during the Old Kingdom, and long oars were used to guide the boat; one steering-oar was enough for a small boat; for a large one however, several oars were required on each side of the stern to guide it aright. These large steering-oars did not differ in shape from the other oars; they were also put into rowlocks, and were secured by a rope to prevent their being lost. The helmsman usually steered standing.

.jpg)

boat from 1900 BC

Ancient-Egyptian-Built Boats

The world’s oldest remains of a “built boat,” one constructed with planks tied together, comes from Egypt and dates to 3000 B.C. The boat were made from planks fitted together by ropes "sewn" through holes, which in turn were filled with bundles of reeds to prevent leaks. The early boats had no keels and were mostly paddled. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, October 31, 2000]

The boat was 75 feet long and 7 to 10 feet wide, with a shallow draft and a narrowing prow and stern. Estimated to have been rowed by 30 men, it was found in Abydos (300 miles south of Cairo), the first capital of the pharaohs, and was used in the burial ritual of the of the pharaoh. The ship was found buried along with 13 other boats.

Dr. Cheryl Ward, an archaeologist at Florida State University, told the New York Times, “It takes a lot of skill to build a boat like the one at Abydos, something we don’t think about in our day of power tools. There had to be trained workers shaping the wood, usually with stone tools. It took planning and discipline and a higher level of organization in a society.”

Ancient Egyptian Mortise and Tenon Boats

A 142-foot-long boat was found buried next to the Great Pyramid of Cheops of Giza. Known as the royal bark of Khufu, and dated to around 2500 B.C. around the same time the pyramid was built, it was made with mortise-and-tenon joints and a frame lashed to the hull that kept the sides from sagging outward.

Hulls were held together with mortises and tenons (slots and wooden pieces) that were fit together with great skill. The mortises (slots) were drilled into the planks. Adjoining planks had mortise in the same places. Tenons (wooden pieces) were placed in the slots to hold the planks together. Wooden pegs or copper nails were then hammered into the tenons to hold them in place. The fit often was so tight that caulking wasn’t needed.

Boat from the Middle Kingdom

Sailing Boats in Ancient Egypt

Nearly all the boats seem to have been adapted for sailing as well as for rowing, except during the Old Kingdom, when sailing seems to have been an art that was little developed. We know of one sail only, and that is a rectangular square-sail which was probably made of papyrus matting. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The mast is very curious, for as one piece of wood was not strong enough alone, the Egyptians used two comparatively slender masts bound together at the top. A strong rope went from the top of the mast to the bows, and another to the stern — these correspond to our shrouds, such as the ropes which keep the mast in place. In addition, six to twelve thinner shrouds were fastened from the upper part of the mast to the back part of the boat.

The yard-arm rested on the point of the mast; the sailors were able to turn it to the right or left by two ropes which passed backwards from the ends of the yard. The sail hung down to the edge of the boat, and was provided in some cases at any rate with a second yard below; it was of considerable size in comparison to the size of the boat. Thus a boat of perhaps 52 feet in length, with oars 10 feet and stccring-oars 16 feet long, would have a mast of 33 feet and a yard of 20 feet, so that the sail would contain from 600 to 700 square feet of canxas. '

The Egyptians mass produced linen for sails. When the wind dropped and the sail was lowered in order to row, the yard was taken off and the mast taken down; the sail was then wrapped round both, and the whole laid on the top of the cabin or hung on forked posts/

Development of Boats in Ancient Egypt

The vessels of which we have hitherto spoken all belong to the time of the Old Kingdom. During the obscure period at the close of this epoch, great improvements were probably introduced, for the vessels of the Middle Kingdom are considerably better than those of earlier date. In our illustration the clumsy steering-oars used during the Old Kingdom have been replaced by a rudder-like devise, which is easily managed with a rope by the helmsman. The two laths used formerly as a substitute for a mast have also been replaced by a strong pole-mast. In this time also the sail is always provided with a lower yard, and the upper one, instead of being fixed to the top of the mast, is fastened to it by movable roperings, so that it can be raised or lowered at will. The rigging has also been very much improved, so that altogether the vessels are far more easy to navigate than they were during the Old Kingdom. Even the large rowboats have their share in these improvements; rowers sit on trestle seats placed on the deck of the vessel; there is also a beautiful cabin with sides of gay matting, with windows, and with a pleasant airy roof, where the women and children of the master can enjoy a cool resting-place during the journey.

For a long time the Egyptian boats did not advance beyond this stage of development, and there is not really much worthy of mention amongst the innovations introduced during the New Kingdom. The most important is the abnormal breadth of the sail. During the Old Kingdom the sail was considerably higher than it was broad; during the Middle Kingdom the breadth somewhat exceeded the height; but during the New Kingdom it sometimes attained such an immense breadth that no pole was long enough to serve as yard, and it became necessary to join two poles together for this purpose. For instance, during the Old Kingdom a large vessel, perhaps 52 feet long, would have a mast of about 33 feet high and a yard 20 feet long. During the Middle Kingdom the mast would be reduced to the height of 16 feet, whilst the yard retained its length of 20 feet.

During the New Kingdom the yard would be lengthened to perhaps 32 feet, thus double the height of the mast. These immense sails naturally required an increase of rigging, which necessitated a fresh arrangement, consequently the mast was furnished with a kind of round head, a lath-box fastened to the top. During the New Kingdom we find in the bows and often also in the stern of the larger sailing vessels, a wooden boarding half the height of a man; this serves as a place for the pilot or the captain “who stands in the bows and does not let his voice be wanting. " The cabin itself is higher than in the older period, and in outward appearance somewhat resembles a house with doors and windows. The baggage of the master is piled up on the flat roof; room must be found there even for his carriage, for no grandee of the New Kingdom traveled without this newfangled means of transport with him. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Advanced Ships in Ancient Egypt

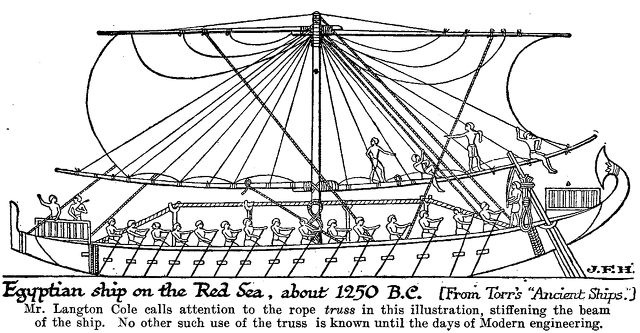

The first known vessels that could handle the waves of the Mediterranean were boats that had stiffer hulls that appeared around 2400 B.C. These vessels didn't have a keel but were kept from tipping over by suspension-bridge-like rope trusses that were attached to upright supports that ran from the bow to stern. The ships were propelled forward by oars and a tall sail mounted on a bipedal mast.

Records dating to the time the Pyramids were built describe vessels traveling to Lebanon to pick up cedar and other valuable woods. An entry on the Palermo Stone, an early record of ancient events, describes an expedition of 40 vessels picking up enough logs to construct 170-foot-long ships. Egyptian ships plied the Red Sea and traveled as far as Punt (near modern-day Somalia) there is an account of one expedition returning with 80,000 measures of myrrh, 6,000 units of electrum (an alloy of gold and silver), 2,600 units of wood, and 23,020 measures of unguent.”

Around 1500 B.C. Egyptians learned how to make keels and internally reinforced hulls. Sails were rigged differently and steering oars were relocated. Around this time two new kinds of ships emerged: sailing ships with wider hulls and smaller crews used for transporting goods and long, narrow oar-driven galleys that were developed for warfare.

Sailing ships transported cargo like wine and olive oil in five- to ten-gallon amphorae (ceramic jugs). Several vessels of this type and their cargos have found by archaeologists. A boat used by Queen Hatshepsut to carry obelisks to Karnak was larger and broader than Admiral Nelson’s “Victory”. The ancient Egyptian vessel was 200 feet long and 70 feet in beam.

Boat Making in Ancient Egypt

Images from the tomb of To, a 5th dynasty official buried in Saqqara offers insight into how Egyptian wooden boats were built. In the early stages tree trunks were trimmed and smoothed with an adz. The logs are sawed into planks and holes were cut into the planks with chisels and mallets. Similar method are still used today.

Egyptian carpenters made boats When native woods were used, we find a complete lack of planks of any great length; instead objects were made by putting together small planks to form one large one.[Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

In boat-making, the little boards were fastened the one over the other like the tiles of a roof; this process, which is unmistakably represented in a picture of the Middle Kingdom, was still in common practice in Egypt in the time of Herodotus, though, like other old Egyptian customs, it is now confined to the Upper Nile.

The following was the method by which they gave the planks of a boat the right curve: when the boat was ready in the rough, the boat-builder of the Old Kingdom drove a post with a fork at the top into the middle of the bottom. Strong ropes were then fastened to the stern and the bow of the boat, and drawn over the fork; the workmen next stuck poles through these ropes and then twisted them round until the boards of the boat had been curved into the necessary shape. The men had of course to exert all their strength, so that the rope should not untwist, and all their work be in vain.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024