Home | Category: Education, Health and Transportation

SEAFARING IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Steve Vinson of the University of Indiana wrote: “Seafaring either to or from Egypt cannot be specifically documented before the Old Kingdom, but evidence points to the possibility of sea contact between Egypt and the Syro-Palestinian coast in the Early Dynastic Period, and it is not implausible to suggest that such contacts could have been established in the Predynastic Period or earlier. Egypt’s wooden boat-building industry appears to extend back that far, and while all currently available evidence is oriented towards Nile River shipping, there is no obvious reason why Predynastic Egyptian vessels could not have navigated coastal waters, as Mesolithic and Neolithic Aegean watercraft certainly did. Old Kingdom texts and images confirm seafaring on both the Mediterranean and Red Seas, and this activity continued throughout documented Egyptian history. By the Roman Period, Egypt was the nexus of a far-flung international maritime system that tied the Mediterranean to distant ports in East Africa, Arabia, and India.[Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“The sources for the history of ancient Egyptian seafaring—that is to say, use of water-craft on the Mediterranean and Red Seas—are, unfortunately, somewhat uneven and less informative than one would like. Far more information (textual, iconographic, and archaeological) is available for the study of riverine ships and shipping. In general, evidence is biased towards the New Kingdom and later periods, but at least some important and interesting material comes from almost every period in Egyptian history.

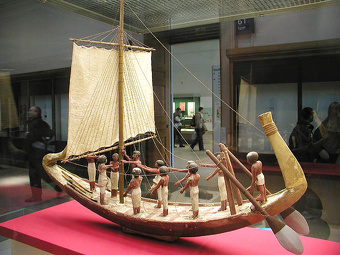

“Royal inscriptions, including both texts and images, are highly useful but not attested in all periods, and their limitations must be kept in mind. Egyptian nautical images are often highly detailed, but the details they provide are limited to exterior structures, most especially rigging. In the New Kingdom, a few tombs include images of ships from Canaan/Syria-Palestine, along with images of foreign traders bringing exotic materials from Western Asia, the Aegean, and Nubia. Numerous boat models come from Egypt, but none can be identified as models of specifically ocean-going craft.

“The texts that accompany nautical images can be informative, but their roots in religious/propagandistic discourses praising royal power must be kept in mind. So too must the interpreter be alert to these texts’ allusions to Egyptian perceptions of the world beyond Egypt—i.e., in part as a place where maat does not necessarily obtain, but also as a place where distant, unknown gods may dwell and where wonderful things may be found.

“Documentary texts dealing with seafaring (as opposed to river transportation) are rare before the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods; one exceptional document is a papyrus from the dockyard annals of Thutmose III, which includes mentions of ships of Keftyw (probably Crete). Likewise, archaeological remains directly connected with seafaring are relatively sparse, so far found only on the Red Sea coast. For all periods, an important source of indirect information is the archaeological and textual attestation of foreign trade.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

SHIPS AND BOATS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

TYPES OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN BOATS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

RIVER TRANSPORT AND USES OF BOATS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MERER'S DIARY: 4,600-YEAR-OLD LOGBOOK ABOUT PYRAMID BOATMEN africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Egyptian Ships and Shipping” by William Franklin Edgerton (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World” by Lionel Casson (1995) Amazon.com;

“The Nile: Traveling Downriver Through Egypt's Past and Present” by Toby Wilkinson (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Nile: History's Greatest River” by Terje Tvedt (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Gift of the Nile?: Ancient Egypt and the Environment (Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections) by Egyptian Expedition, Thomas Schneider, Christine L. Johnston (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Nile and Ancient Egypt: Changing Land- and Waterscapes, from the Neolithic to the Roman Era”, Illustrated by Judith Bunbury (2019) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Boats and Ships” by Steve Vinson (2008) Amazon.com;

“A Categorisation and Examination of Egyptian Ships and Boats from the Rise of the Old to the End of the Middle Kingdoms by Michael Allen Stephens (2012) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Boats and Ships” by Sean McGrail (2008) Amazon.com;

“Ship 17 a Baris from Thonis-Heracleion” (Ships and boats of the Canopic Region in Egypt) by Alexander Belov (2018) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The World of Ancient Egypt: A Daily Life Encyclopedia" by Peter Lacovara, director of the Ancient Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage Fund (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2016) Amazon.com

Sea-Worthy Ships in Ancient Egypt

The first known vessels that could handle the waves of the Mediterranean were boats that had stiffer hulls that appeared around 2400 B.C. These vessels didn't have a keel but were kept from tipping over by suspension-bridge-like rope trusses that were attached to upright supports that ran from the bow to stern. The ships were propelled forward by oars and a tall sail mounted on a bipedal mast.

Records dating to the time the Pyramids were built describe vessels traveling to Lebanon to pick up cedar and other valuable woods. An entry on the Palermo Stone, an early record of ancient events, describes an expedition of 40 vessels picking up enough logs to construct 170-foot-long ships. Egyptian ships plied the Red Sea and traveled as far as Punt (near modern-day Somalia) there is an account of one expedition returning with 80,000 measures of myrrh, 6,000 units of electrum (an alloy of gold and silver), 2,600 units of wood, and 23,020 measures of unguent.”

Around 1500 B.C. Egyptians learned how to make keels and internally reinforced hulls. Sails were rigged differently and steering oars were relocated. Around this time two new kinds of ships emerged: sailing ships with wider hulls and smaller crews used for transporting goods and long, narrow oar-driven galleys that were developed for warfare.

Sailing ships transported cargo like wine and olive oil in five- to ten-gallon amphorae (ceramic jugs). Several vessels of this type and their cargoes have found by archaeologists. A boat used by Queen Hatshepsut to carry obelisks to Karnak was larger and broader than Admiral Nelson’s “Victory”. The ancient Egyptian vessel was 200 feet long and 70 feet in beam.

Seafaring in the Prehistoric, Predynastic and Early Dynasty Egypt

Steve Vinson of the University of Indiana wrote: “Seafaring, either by Egyptians or by others traveling to Egypt, cannot be documented before the Old Kingdom, but it might well have begun in the Predynastic Period, or even earlier. It is very probably the case that Egypt’s wooden boat/ship-building technology was well developed by the late Gerzean/Naqada II Period, when boat imagery (especially images of so-called “sickle- shaped” boats, characterized by crescentic hulls with multiple paddles, deck structures, standards, and palm-frond-like bow decorations) is common in both rock art and in pottery decoration. Such representations offer us no direct evidence for the material used to construct Egypt’s “sickle-shaped” boats, but archaeological evidence suggests a high general level of technical skill in working wood in the Predynastic Period. Construction of wooden boats is certain by the 1st Dynasty. While all extant evidence for such early craft points towards their use on the Nile, it is not difficult to imagine that Egyptian vessels could have sailed on the Mediterranean or Red Sea before the Old Kingdom; there is no reason to doubt that Egypt’s Predynastic and Early Dynastic vessels were at least as well constructed as the Mesolithic water-craft that brought obsidian traders to the Greek island of Melos, or the Neolithic water-craft that brought the earliest settlers to Crete and Cyprus. Moreover, there is considerable evidence for the importation of exotic materials into Egypt in the Gerzean/Naqada II Period. To what extent this can be attributed to either land transportation or seafaring cannot be definitely determined. [Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“We can, however, certainly discount earlier Egyptologists’ theories of circum-Arabian voyages from lower Mesopotamia to Egypt’s Red Sea coast by Uruk-era Sumerians who (allegedly) conquered Predynastic Egypt and founded the 1st Dynasty. A carved ivory knife-handle said to be from Gebel el-Arak in Upper Egypt (now in the Louvre) shows boats resembling vessels portrayed on Uruk- era cylinder seals, as well as sickle-shaped boats that somewhat resemble vessels on Gerzean/Naqada II painted pottery, amid a battle in progress. This scene, as well as other images of “foreign” ships, was once generally interpreted as showing such an invasion , but since the 1970s, this interpretation has lost considerable favor. In all likelihood, the undoubted Mesopotamian flavor of the Gebel el-Arak imagery—along with other examples of Mesopotamian cultural influences that reached Egypt in the Predynastic Period—can be explained by diffusion via Syria, which was reached by Sumerians during the Uruk Expansion in the late fourth millennium B.C., rather than by a sea-route connecting Mesopotamia and Egypt in this period.

“By the 1st Dynasty, contacts between Egypt and western Asia had accelerated and sea contact seems certain. An Egyptian cup, datable to the Early Dynastic Period, was found by an Israeli fishing trawler off the coast of Gaza in the 1980s. We know that, in the Early Dynastic Period, Lebanese cedar was imported into Egypt for the construction of royal tombs, and a Dynasty 1 label from the tomb of Aha (second king of the dynasty) includes images of ships labeled with the word mr “cedar”, which suggests a connection between Egyptian cargo ships and the importation of Lebanese or Syrian wood. It is unclear whether the word “cedar” here refers to the vessel’s construction or its cargo. Both are possible, since cedar was a well- attested ship-construction material in Egypt (most notably the 4th Dynasty funerary vessel of Khufu), and other evidence makes it all but certain that, not later than the 4th Dynasty, imported wood came to Egypt at least sometimes by sea (see Old Kingdom below). That said, it is impossible from the evidence at hand to say anything specific about how any Pre- or Early Dynastic seafaring would have been organized, beyond the probability that much, if not all, of this activity would have been in the hands of the ruling elite. Nor is it possible to estimate how important it was to Egypt’s overall economy.”

trade ship carrying frankincense, trees and other goods

Seafaring in the Old and Middle Kingdoms (2649–1640 B.C.)

Steve Vinson of the University of Indiana wrote: “The Palermo Stone reports for the 4th Dynasty: “bringing 40 ships filled [mH] with coniferous wood [aS]” in the reign of Sneferu. This would appear to confirm sea-going transportation of wood between Egypt and the Syro-Palestinian coast from at least the 4th Dynasty, if not earlier, though whether the ships involved were “Egyptian” or “Canaanite/Syro-Palestinian” cannot be determined. The first Old Kingdom representation of what appears to be a sea- going craft appears in the 5th Dynasty sun temple of Sahura. This much- discussed relief shows vessels that appear to be rigged like standard Egyptian river-boats of the Old Kingdom (i.e., with bi-pod, rather than mono-pod, masts), but that also show stoutly-lashed bulwarks (uppermost hull planking) and a hogging truss (heavy cable running bow-to-stern, capable of being tightened to prevent the ends of the ship from sagging), which would suggest a ship designed to withstand the rigors of sea travel. [Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“The presence aboard of bearded persons who appear to be western Asian, along with an inscription presented as the arriving seafarers’ praise to Sahura, has led to the conclusion that this vessel probably represents a foreign craft arriving in Egypt. Although the word does not actually appear here, it may well be that this is a “Byblos” ship (kbnt). This ship name does not appear until the 6th Dynasty, in the inscription of the courtier Pepynakht. Pepynakht reports that he had been assigned to bring back to Egypt the body of a murdered Egyptian who had been sent to Western Asia to oversee the construction of a “Byblos” boat, which had actually been intended for an expedition to Punt (probably southern Sudan and/or Somalia, perhaps also including southern Arabia). This suggests that in the Old Kingdom, Egyptians may have depended at least in part on Western Asian ship-builders for their ocean-going craft.

“In the Middle Kingdom, we encounter “Byblos” boats (kbnjwt) once again in a Wadi Hammamat inscription commemorating an expedition to Punt. This time, the ships are actually constructed on the Red Sea coast— thus, most probably by Egyptians (Couyat and Montet 1912: 82 - 83; see 1.9 for reference to "Byblos" boats and 1.14 for their construction on the coast). In general, the best evidence for Middle Kingdom seafaring reflects Red Sea shipping. One of the best-known Middle Kingdom Egyptian literary compositions, the Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor, is centered on a voyage to Punt. The details given for the size of the sailor’s ship (120 cubits by 40 cubits, or about 60 meters by 20 meters) and its crew (120 men) should not be taken seriously (cf. Vinson 1997a; 1998: 15ff. for the much smaller crews known from actual documentary texts for working Nile vessels), but the tale does include a plausible list of products from Punt (e.g., myrrh, various oils, giraffe tails, elephant ivory) and reflects the genuine hazards of shipping on the Red Sea. One archaeologically documented Red Sea embarkation point during the Middle Kingdom was Marsa Gawasis, where shrines constructed of stone anchors have been discovered. However, Egyptian contacts with the Levantine coast, especially Byblos, and the island of Crete are also documented or suggested in the Middle Kingdom.”

Trade routes

Seafaring in the New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.)

Steve Vinson of the University of Indiana wrote: “Punt continued to be a focal point of Egyptian seafaring in the New Kingdom, with Hatshepsut’s Punt reliefs at Deir el-Bahri constituting perhaps the finest preserved examples of Egyptian nautical art. The vessels portrayed here show classic Egyptian lines and rigging, and suggest the very highest achievements of Egypt’s traditional boat- and shipbuilding craft. Further evidence for Red Sea sailing in the 18th Dynasty has more recently been brought to light by Boston University archaeologist Kathryn Bard, who in 2004 discovered a cave at Marsa Gawasis containing fragments of rope, steering-oar, and hull-planking that may date to or near the reign of Hatshepsut. The Ramesside Papyrus Harris I reports a voyage to Punt in the reign of Ramses III. [Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“As in the Old and Middle Kingdoms, Egypt in the New Kingdom was also in maritime contact with the Late Bronze Age civilizations of the Eastern Mediterranean and Aegean. A number of 18th Dynasty tomb reliefs portray Minoan traders, and an important relief from the tomb of Ken-Amun shows a Canaanite ship in port. This ship resembles contemporaneous Egyptian ships like the Hatshepsut Punt-expedition ships in some respects, notably the rigging; but the overall hull shape is characteristically Near Eastern. New Kingdom texts also reflect these connections. The dockyard annals of Thutmose III refer to ships of Keftyw, likely Crete or the Aegean more generally, and ships from Canaan are described in the Kamose Stela from the terminal Second Intermediate Period.

“The Kamose-stela ships are said to carry luxurious cargo including gold, silver, lapis lazuli, various sorts of wood, and other raw materials; curiously, the only finished products are “countless copper axes.” The summary writing used here for “copper” (Hmt) could also bear the reading Hsmn (“bronze”) per Habachi. Although the common Egyptian word for “axe” used here (mjnb) is admittedly attested nowhere else in this sense, it may be that the reference in the Kamose Stela is actually to copper ingots of the “ox- hide” type. The shape of such ingots has been compared to that of Aegean double axes of the Late Bronze Age. The rest of the cargos described on these ships comprise raw, unfinished products; copper ingots would be a more plausible bulk cargo than literal finished axes (cf. the large cargo of ox-hide ingots in the late fourteenth- century B.C. Uluburun shipwreck [Pulak 2001]; also the even larger cargo of copper ingots described in Amarna Letter 35 [Moran 1992: 107ff.]).

“Archaeologically, the late-18th-Dynasty-era Uluburun shipwreck shows the extent towhich Egypt was embedded in maritime and overland routes that extended throughout Africa, Western Asia, and southern and eastern Europe. Perhaps the most important Egyptian artifact from the Uluburun wreck is the golden scarab of Nefertiti. However, other important objects that suggest Egypt’s central location on many of the important trade routes of the Late Bronze Age world include raw ebony and ivory and ostrich eggshells, which may have been transshipped through Egypt from tropical Africa, and perhaps the wreck’s glass ingots, which some have argued to be of Egyptian origin.”

More Advanced Ships Appear in New Kingdom Egypt

Steve Vinson of the University of Indiana wrote: “By the end of the 18th Dynasty, new principles in ship design, likely derived from the Aegean, are visible in Egypt. A relief from Saqqara, probably to be dated to the reign of Horemheb, is the first known example of a ship rigged with brails—Venetian-blind-like lines that could be used to shorten or shape loose-footed sails, and that were to characterize the standard sea-going rig of classical Mediterranean antiquity. Up until this point, Egyptian ships—as well as sea-going ships that appear in the art of Mycenaean Greece, Minoan Crete, and the island of Thera—were almost always shown with the feet of their sails secured with booms. It could be that ships with these characteristics were brought to Egypt by raiders or traders from the Aegean, who are attested as early as the Amarna Period and who seem to have become increasingly irritating to the Egyptians in the Ramesside Period. [Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“The best illustration of Egyptian seagoing ships in the late New Kingdom occurs in the 20th Dynasty sea-battle relief at Medinet Habu, showing Egypt’s fleet under Ramses III in a pitched battle against the invading Sea Peoples. In the relief, both sides’ ships are shown with the new brailed rig. Since the sailors shown fighting on the Egyptian side are almost all wearing attire closely similar to that of the invading Sea Peoples, it seems likely that the Egyptian navy was made up, at least in this instance, of ships actually owned by Egypt’s own Sea-People allies or mercenaries—the Sherden or others.

Battle with the Sea People

“Were other innovations in ship design adopted by the Egyptians? The late fourteenth-century B.C. Uluburun shipwreck features a sea-going vessel with a construction similar to that of later Greek and Roman ships on the Mediterranean—that is, with pegged mortise-and-tenon joints—but unlike that of earlier Egyptian ships with lashed construction. A fascinating letter, in Akkadian, from the court of Ramses II speaks of an Egyptian ship that had been sent to the Hittites, evidently for the purpose of allowing Hittite shipwrights to copy it. The only constructional details we get are that the ship apparently had internal framing (ribs), and that it was caulked with pitch, a practice now paralleled archaeologically by a water-proofing agent observed on some planks salvaged from New Kingdom sea-going ships found at Marsa Gawasis (Ward and Zazzaro fc.; cf. Vinson 1996: 200 for the practice in Greco-Roman antiquity and one occurrence in Roman Egypt). Whether this was a traditionally constructed Egyptian hull, or a new-style hull based on Eastern Mediterranean/Aegean principles, is unknown.

“Egyptian dependence on foreign commercial ships at the end of the New Kingdom is suggested in the Report of Wenamun, a terminal New Kingdom/early Third Intermediate Period literary composition that describes the experiences of a priest of Amun who is dispatched to Phoenicia to secure wood for the renovation of the sacred bark of Amun. In this tale, Wenamun has to endure the sneers of his Phoenician interlocutors who point out that he has come to Lebanon on a foreign ship. Wenamun’s protest that any ship chartered by an Egyptian is, ipso facto, an Egyptian ship, is shown by the story itself to be empty bluster.”

Seafaring in the Late, Ptolemaic and Roman Periods (712 B.C.–364 A.D.)

Beyond the period reflected in the Report of Wenamun, it is not easy to trace any of Egypt’s own seafaring ventures. In the first millennium B.C., Egypt certainly maintained continuous, if fluctuating, contact with Syria- Palestine; many of the Egyptian artifacts discovered in Western Asia during this period may have been carried by sea, perhaps by Phoenician seafaring merchants. Seafaring again becomes clearly visible in Egyptian history largely in the context of Greeks coming to Egypt as traders or as mercenaries. As Greece recovered from the collapse of Mycenaean civilization, Iron- Age Greek seafarers spread throughout the Mediterranean. The most important early Greek entrepôt in Egypt was the east-Delta city of Naukratis, founded in the seventh century B.C.. According to Herodotus , Naukratis was originally conceived as a controlled trading point beyond which Greeks were not supposed to go (not unlike Nagasaki in Japan under the Tokugawa Shogunate). Egypt fell to the Achaemenid Persians in 525 B.C., and integration into the Persian empire appears to have promoted Egyptian trade in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. This eastern trade was facilitated by the construction of a canal linking the Nile to the Red Sea through the Wadi Tumilat. A series of stelae in hieroglyphic and Persian marks the route of this canal, which continued in use during the Ptolemaic Period. [Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Many Greeks were already settled throughout the land of Egypt by the time of Alexander the Great’s conquest in 332 B.C.. The new dynasty founded after Alexander’s death in 323 by his general Ptolemy son of Lagus turned the new city of Alexandria into one of the most important commercial and cultural centers of the Hellenistic Mediterranean. After Egypt was conquered by Rome in 30 B.C., Alexandria became the port of embarkation for the vast quantities of grain taken from Egypt to feed the Roman mob. By the end of the Ptolemaic Period, a Greek skipper appears to have discovered the monsoon system that blows across the Indian Ocean, enabling the establishment of a rapid, open-water trade route between Egypt and India; this route only grew in importance following the Roman conquest. The most important document detailing this route is the Periplus Maris Erythraei (“Sailing Directions for the Erythraean Sea,” a term designating both our Red Sea and Indian Ocean). The Periplus is a first-century CE Greek-language manual, probably written by a Greek-speaking Egyptian skipper or at least a Greek skipper with considerable knowledge of Egypt, that describes maritime routes for East Africa, Arabia, and India, as well as commercial opportunities and political/cultural conditions in the associated major ports.

“Hellenistic and Roman ships departed from Egyptian Red Sea ports like Myos Hormos or Berenike, which were accessible via desert routes connecting the Red Sea to the Nile Valley. These routes appear to have ended at Coptos, near the eastern-most bend of the Nile River. In the ninth year (89 – 90 CE) of the Roman emperor Domitian, an important inscription was executed near Coptos, detailing tolls to be paid by various classes of persons, animals, or items traveling or being transported along the desert route. Tolls varied widely—a “Red Sea skipper” paid eight drachmas, while “women for companionship” were assessed 108 drachmas! The eastern-most end of the Red Sea-Indian Ocean route can also be traced archaeologically through finds of Roman material, notably glass, which occurs in numerous sites along the coast of India.”

Herodotus on Egyptian Sea Navigation

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “And I think that their account of the country was true. For even if a man has not heard it before, he can readily see, if he has sense, that that Egypt to which the Greeks sail is land deposited for the Egyptians, the river's gift—not only the lower country, but even the land as far as three days' voyage above the lake, which is of the same nature as the other, although the priests did not say this, too. For this is the nature of the land of Egypt: in the first place, when you approach it from the sea and are still a day's sail from land, if you let down a sounding line you will bring up mud from a depth of eleven fathoms. This shows that the deposit from the land reaches this far. 6. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“Further, the length of the seacoast of Egypt itself is sixty “schoeni”7 —of Egypt, that is, as we judge it to be, reaching from the Plinthinete gulf to the Serbonian marsh, which is under the Casian mountain—between these there is this length of sixty schoeni. Men that have scant land measure by feet; those that have more, by miles; those that have much land, by parasangs; and those who have great abundance of it, by schoeni. The parasang is three and three quarters miles, and the schoenus, which is an Egyptian measure, is twice that. 7.

“By this reckoning, then, the seaboard of Egypt will be four hundred and fifty miles in length. Inland from the sea as far as Heliopolis, Egypt is a wide land, all flat and watery and marshy. From the sea up to Heliopolis is a journey about as long as the way from the altar of the twelve gods at Athens to the temple of Olympian Zeus at Pisa. If a reckoning is made, only a little difference of length, not more than two miles, will be found between these two journeys; for the journey from Athens to Pisa is two miles short of two hundred, which is the number of miles between the sea and Heliopolis.”

Transporting Wood by Sea in Ancient Egypt

Steve Vinson of Indiana University wrote: “The transport of large quantities of wood, especially from western Asia, is documented from an early period in Egypt; much, if not all, of this cargo must have been transported by sea. Imported wood was used in a number of First Dynasty royal tombs, and a First Dynasty label from the tomb of Aha associates an image of a ship with the word mr, although it is not clear whether the reference here is to the vessel’s construction or its cargo. From the Fourth Dynasty (reign of Seneferu), the Palermo Stone records a shipment of some 40 ships loaded with coniferous wood. [Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“More details of the procedures by which the long, straight timbers available from the area of Lebanon and Syria were transported to Egypt come from the New Kingdom, when battle reliefs of Sety I at Karnak show foreign princes cutting down trees for transport back to Egypt, while others, possibly lower-status individuals, lower the trees with cables attached to the upper branches. From the Third Intermediate Period, the Report of Wenamun describes large tree-trunks being dragged down to the shore.

“Wenamun reports that a limited number of wooden ship components were placed aboard a transport ship bound for Egypt as a preliminary, good-faith shipment, but aside from this, no Egyptian text or image describes the specific modalities of the actual sea- transport of large timber. One might compare a first-millennium B.C. Assyrian relief from the palace of Sargon at Khorsabad, which shows tree-trunks being towed behind Phoenician transport ships off the Syrian coast. Such towing may have been the (or a) method by which the Egyptians, or Western Asians in the service of Egypt, also moved cargoes of the largest trunks of wood back to Egypt.”

states in the Middle East and Asia at the time of Ancient Egypt

4,500-Year-Old Ancient Egyptians Red Sea Port

Wadi al-Jarf is an ancient Egyptian port dated to 2600 B.C and linked with the Giza pyramid builders. Excavated bt French archaeologists Pierre Tallet and Gregory Marouard, it is 120 kilometers south of Suez , which in turn is 125 kilometers west of Cairo, meaning than Wadi al-Jarf was a considerable distance form the Pyramids of Giza. Caves in area had served as a kind of boat storage depot during the fourth dynasty of the Old Kingdom. In 2013, in some of these caves Tallet and his team found entire rolls of papyrus, some a few feet long and still relatively intact,written in hieroglyphics as well as hieratic, the cursive script the ancient Egyptians used for everyday communication. These rolls turned out to be the oldest known papyri in the world. The port is also regarded as the world’s oldest. [Source: Alexander Stille, Smithsonian Magazine, October 2015 |=|]

Alexander Stille wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “Wadi al-Jarf lies where the Sinai is a mere 35 miles away, so close you can see the mountains in the Sinai that were the entry to a mining district. The Egyptian site has yielded many revelations along with the trove of papyri. In the harbor, Tallet and his team found an ancient L-shaped stone jetty more than 600 feet long that was built to create a safe harbor for boats. They found some 130 anchors—nearly quadrupling the number of ancient Egyptian anchors located. The 30 gallery-caves carefully dug into the mountainside—ranging from 50 to more than 100 feet in length—were triple the number of boat galleries at Ayn Soukhna. For a harbor constructed 4,600 years ago, this was an enterprise on a truly grand scale. |=|

“Yet it was used for a very short time. All the evidence that Tallet and his colleagues have gathered indicates that the harbor was active in the fourth dynasty, concentrated during the reign of one pharaoh, Khufu. What emerges clearly from Tallet’s excavation is that the port was crucial to the pyramid-building project. The Egyptians needed massive amounts of copper—the hardest metal then available—with which to cut the pyramid stones. The principal source of copper was the mines in the Sinai just opposite Wadi al-Jarf. The reason that the ancients abandoned the harbor in favor of Ayn Soukhna would appear to be logistical: Ayn Soukhna is only about 75 miles from the capital of ancient Egypt. Reaching Wadi al-Jarf involved a considerably longer overland trip, even though it was closer to the Sinai mining district. |=|

“After visiting Wadi al-Jarf, Mark Lehner, an American Egyptologist, was bowled over by the connections between Giza and this distant harbor. Tallet is convinced that harbors such as Wadi al-Jarf and Ayn Soukhna served mainly as supply hubs. Since there were few sources of food in the Sinai, Merer and other managers were responsible for getting food from Egypt’s rich agricultural lands along the Nile to the thousands of men working in the Sinai mine fields, as well as retrieving the copper and turquoise from the Sinai. In all likelihood, they operated the harbor only during the spring and summer when the Red Sea was relatively calm. They then dragged the boats up to the rock face and stored them in the galleries for safekeeping until the next spring. |=|

“Ancient Egypt’s maritime activities also served political and symbolic purposes, Tallet argues. It was important for the Egyptian kings to demonstrate their presence and control over the whole national territory, especially its more remote parts, in order to assert the essential unity of Egypt. “Sinai had great symbolic importance for them as it was one of the farthest points they could reach,” Tallet says. “In the Sinai the inscriptions are explaining the mightiness of the king, the wealth of the king, how the king is governing its country. On the outer limits of the Egyptian universe you have a need to show the power of the king.” |=|

“In fact, their control of the periphery was rather fragile. Distant and inhospitable Sinai, with its barren landscape and hostile Bedouin inhabitants, represented a challenge for the pharaohs; one inscription records an Egyptian expedition massacred by Bedouin warriors, Tallet says. Nor were the Egyptians always able to hold on to their camps along the Red Sea. “We have evidence from Ayn Soukhna that the site was destroyed several times. There was a big fire in one of the galleries....It was probably difficult for them to control the area.”

Herodotus on Naucratis, Egypt’s Trading Port

Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: “Amasis became a philhellene, and besides other services which he did for some of the Greeks, he gave those who came to Egypt the city of Naucratis to live in; and to those who travelled to the country without wanting to settle there, he gave lands where they might set up altars and make holy places for their gods. Of these the greatest and most famous and most visited precinct is that which is called the Hellenion, founded jointly by the Ionian cities of Chios, Teos, Phocaea, and Clazomenae, the Dorian cities of Rhodes, Cnidus, Halicarnassus, and Phaselis, and one Aeolian city, Mytilene. It is to these that the precinct belongs, and these are the cities that furnish overseers of the trading port; if any other cities advance claims, they claim what does not belong to them. The Aeginetans made a precinct of their own, sacred to Zeus; and so did the Samians for Hera and the Milesians for Apollo. 179. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

“Naucratis was in the past the only trading port in Egypt. Whoever came to any other mouth of the Nile had to swear that he had not come intentionally, and had then to take his ship and sail to the Canobic mouth; or if he could not sail against contrary winds, he had to carry his cargo in barges around the Delta until he came to Naucratis. In such esteem was Naucratis held. 180.

“When the Amphictyons paid three hundred talents to have the temple that now stands at Delphi finished (as that which was formerly there burnt down by accident), it was the Delphians' lot to pay a fourth of the cost. They went about from city to city collecting gifts, and got most from Egypt; for Amasis gave them a thousand talents' weight of astringent earth,74 and the Greek settlers in Egypt twenty minae.”

In 2012, Archaeology magazine reported: A 2,300-year-old harbor has been uncovered off the coast of the Israeli city of Acre. An Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) and University of Rhode the only one in a protected natural bay. “Recently, a find was uncovered that suggests we are excavating part of [AcRas] military port,” says Kobi Sharvit, director of the IAA’s Marine Archaeology Unit. “We know the pharaoh Ptolemy Philadelphus built a harbor for his fleet at this time. Usually military ships were kept out of the water in ‘shipshades’ like what we found here. ” The size and design of the structure suits warships from that period. Large mooring stones, pottery vessels, and metallic objects, many of military function, were also found. Initial examination reveals the items originated across the eastern Mediterranean, including at Aegean Sea islands such as Knidos, Rhodes, and Kos. Sharvit’s team will next attempt to determine when the harbor was destroyed. [Source: Mati Milstein, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2012]

Pirates in Ancient Egypt

Mark Woolmer wrote in National Geographic: Some of the earliest written accounts of piracy come from Egypt. One of the first is an inscription from the reign of Pharaoh Amenhotep III (1390-1353 B.C.) that describes having to establish defenses in the Nile Delta against maritime raiders. These raiders were perhaps the first true pirates, as they attacked anyone of any nationality and owed their allegiance to no one. [Source: Mark Woolmer, National Geographic, April 17, 2020]

More ancient accounts come from the Amarna Letters, a series of diplomatic correspondences between the Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten and allied and vassal states. Written on clay tablets between 1360 and 1332 B.C., they touch on many concerns, including piracy. The tablets record that two groups of pirates, the Lukka and Sherden, were causing substantial disruption to regional commerce and security. Correspondence between the king of Alashiya (modern Cyprus) and the Egyptian pharaoh reveals just how much of a threat the Lukka (based in modern-day Turkey) posed. Having vigorously denied that the people of Alashiya had allied themselves with the pirates, the king then claims to have introduced countermeasures, and states he would punish any of his subjects involved in piracy.

Another important Egyptian text sheds light on a feared and mysterious group of marine marauders: the Sea Peoples. In The Tale of Wenamun, a work of fiction written around 1000 B.C., the Tjeker (a subset of the Sea Peoples) controlled the coastline between southern Israel and Byblos (central Lebanon) and attacked merchant shipping with impunity. The titular Wenamun turns to piracy in a desperate effort to replace the money that had been stolen by one of his crew. Despite the Tjeker not being directly involved in the crime, Wenamun blames their leader for failing to apprehend the criminal and so seizes a Tjeker ship and takes a quantity of silver.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024