Home | Category: Education, Health and Transportation

RIVER TRAVEL IN ANCIENT EGYPT

In ancient Egypt — which for the most part consisted of a narrow valley of a great river — that river becomes the natural highway for all communication, especially when, as in Egypt, the country is difficult to traverse throughout a great part of the year. The Nile and its canals were the ordinary roads of the Egyptians; baggage of all kinds was carried by boat, all journeys were undertaken by water, and even the images of the gods went in procession on board the Nile boats — how indeed should a god travel except by boat? [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

This was such an understood matter that it is difficult to find a word in the language that signifies to travel; the terms used were chojit to go up stream, and chod to go down stream. The first word was used in speaking of any journey southwards, the latter of any journey northwards — even when it might signify traveling through the desert. ' Under these circumstances it was natural that the building of river boats should be early developed as a national art.

Steve Vinson of the University of Indiana wrote: ““Boats in ancient Egypt were ubiquitous and crucially important to many aspects of Egyptian economic, political, and religious/ideological life. Four main categories of uses can be discussed: basic travel/transportation, military, religious/cere- monial, and fishing. Examples of each can be traced from the formative period of Egyptian history down to the close of Egypt’s traditional culture in the fourth century CE. One terminological problem is to identify a dividing line between “boats” and “ships.” For the purpose of this article, the term “ship” is arbitrarily taken to mean craft working entirely or primarily at sea (i.e., on the Red Sea or Mediterranean). Therefore, we confine ourselves here as far as possible to water craft of any size that were intended primarily for service on the Nile.” [Source:Steve Vinson, University of Indiana, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

RELATED ARTICLES:

SHIPS AND BOATS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

TYPES OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN BOATS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SEA TRAVEL IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MERER'S DIARY: 4,600-YEAR-OLD LOGBOOK ABOUT PYRAMID BOATMEN africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Nile: History's Greatest River” by Terje Tvedt (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Nile: Traveling Downriver Through Egypt's Past and Present” by Toby Wilkinson (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Gift of the Nile?: Ancient Egypt and the Environment (Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections) by Egyptian Expedition, Thomas Schneider, Christine L. Johnston (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Nile and Ancient Egypt: Changing Land- and Waterscapes, from the Neolithic to the Roman Era”, Illustrated by Judith Bunbury (2019) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Ships and Shipping” by William Franklin Edgerton (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World” by Lionel Casson (1995) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Boats and Ships” by Steve Vinson (2008) Amazon.com;

“A Categorisation and Examination of Egyptian Ships and Boats from the Rise of the Old to the End of the Middle Kingdoms by Michael Allen Stephens (2012) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Boats and Ships” by Sean McGrail (2008) Amazon.com;

“Ship 17 a Baris from Thonis-Heracleion” (Ships and boats of the Canopic Region in Egypt) by Alexander Belov (2018) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Egypt” by Kasia Szpakowska (2007) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The World of Ancient Egypt: A Daily Life Encyclopedia" by Peter Lacovara, director of the Ancient Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage Fund (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2016) Amazon.com

Boats as a Means of Transportation in Ancient Egypt

Steve Vinson of the University of Indiana wrote: The earliest evidence for the use of boats in Egypt usually comes in religious contexts— either funeral (like the common images of boats on Naqada II/Gerzean pots encountered in Predynastic graves) or in rock art that was, presumably, executed for ceremonial/magical purposes. That said, the ubiquity of the images would appear to confirm that boats must have been an increasingly important part of the daily life of Egyptians in the late Predynastic Period. [Source: Steve Vinson, University of Indiana, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“The spread of Egypt’s Naqada II/Gerzean throughout the Nile Valley would have been greatly facilitated by improved river travel; it is probably no coincidence that images of boats with sails first occur at the very end of the Predynastic Period, or just at the cusp of the period in which a single group of rulers was able to extend political power, economic control, and cultural uniformity throughout the Nile Valley.

“By the Old Kingdom, images of boats carrying every-day cargo, especially food- stuffs, is common in Egyptian tomb art, and Egyptian texts of many types—literary as well as documentary—record the use of boats for basic transportation. Especially common in the written record are mentions of grain transport and the transportation of stone, both as raw material for construction or in more-or-less worked forms like columns or obelisks. Both grain and stone were of prime interest to large governmental and/or temple bureaucracies, so their prominence in the written and iconographic record is to be expected. Nevertheless, many other types of cargo can be documented, including bread, cattle, vegetables, fish, and wood. The evidence for this sort of basic transportation of every-day commodities is extremely rich, particularly in the New Kingdom, from when two transport vessel’s logs are preserved, along with numerous papyri and ostraca that document shipping of all kinds. Transport shipping on the Nile is even more copiously documented in the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, in both Greek and in Demotic sources.”

Military Use of Boats in Ancient Egypt

Steve Vinson of the University of Indiana wrote: “The connection of boats with warfare can be traced back to the Predynastic Period. Possibly the earliest image of boats connected to combat in Egyptian art is the Gebel el- Arak knife handle, an ivory knife handle apparently of Naqada II/Gerzean date, which shows two rows of boats of contrasting designs underneath two registers of men fighting. Because the boats in the upper of the two rows shows hulls that strongly resemble craft depicted on contemporaneous representations from Mesopotamia, the Gebel el-Arak knife handle was once thought to provide strong evidence for the theory of the infiltration into Egypt around 3100 B.C. of a “Dynastic Race,” perhaps from in or near the region of Sumer. Supposedly, the maritime invaders of this “Dynastic Race” will have sailed southeast (!) down the Persian Gulf, circumnavigated Arabia, entered Egypt on the western Red Sea coast, portaged their boats through the Eastern Desert (where numerous allegedly “foreign” boat petroglyphs were found), and then, over time, come to dominate the indigenous, Predynastic Egyptians and imposed on them a centralized, literate state. [Source: Steve Vinson, University of Indiana, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“However, the “Dynastic Race” model, first proposed in the late nineteenth century (in the hey-day of the highly-racially-conscious British imperial project in Egypt, see Vinson 2004), has long been abandoned on multiple grounds. It is therefore hard to know exactly what to make of the Mesopotamian-looking vessels on the knife handle, which are quite unparalleled in other known examples of Predynastic Egyptian nautical art. It seems likely that the Mesopotamian imagery seen here is the result of a range of Mesopotamian cultural importations into late Predynastic Egypt, probably via Syria, reached by Sumerians during the Uruk Expansion of the late fourth millennium B.C.. Military conflict between fleets commanded by Predynastic Egyptians and invading Uruk-era Mesopotamians is probably not the explanation. On the other hand, whoever executed the Gebel el-Arak image was certainly familiar with the notion that boats could be used in warfare.

“In the 1st Dynasty, a petroglyph connected to king Djer at the site Gebel Sheikh Suliman appears to show Nubian captives or slain surrounding a boat, which perhaps indicates a water-borne expedition into Nubia. The 6th Dynasty autobiography of Weni reports the use of boats to launch a sea-borne attack somewhere off the coast of Syria-Palestine at a place he calls “Antelope Nose”. Boats must have been used frequently for military operations, but depictions of such are surprisingly scarce. One excellent, but rare, example is a group of three rowed river boats shown in a wall painting from the 11th Dynasty Theban tomb of an official of Mentuhotep I named Intef. Aside from the rowers, the boats also carry archers and soldiers armed with shields and battle-axes. Who the enemy is, however, is unfortunately unclear.

“At the end of the First Intermediate Period, the Kamose Stela describes Egyptian troops under the Theban king Kamose moving northward in a battle fleet from Thebes to attack the Hyksos at Avaris. From the very early 18th Dynasty, the autobiography of Ahmose, son of Ebana, who had made his career in the military serving aboard combat vessels, describes fighting from Nile boats both at Avaris (under the command of Kamose’s younger brother Ahmose, who finally defeated the Hyksos and reestablished centralized rule in Egypt as first king of the 18th Dynasty) and two invasions of Nubia in which Nile boats were used to convey Egyptian armies (under the commands of Amenhotep I and Thutmose I).

“The only naval engagement actually portrayed in Egyptian art is the great battle against the People of the Sea in the funerary temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu, which appears to have taken place in the Nile Delta, not in the open sea. It is not, however, clear that any of the vessels involved are actually “Egyptian,” if by that we mean a vessel built, crewed, and commanded by Egyptians. It is notable that the ships on both sides of the battle are rigged with a new, non-Egyptian technology called “brails” (Venetian-blind-like cords that permitted rapid shortening and easy reshaping of sails), and the attire of the great majority of “Egyptian” marines suggests that they could be ethnically or culturally connected to the invading Sea Peoples. If so, it could be that the “Egyptian” fleet is actually a mercenary fleet.

“With the demise of the New Kingdom, boats certainly continued to be used for military purposes on the Nile. The great stela of the Nubian king Piankhy describes the fleet used to move his troops against his Libyan enemies in the Egyptian Delta, and the Libyan fleet that tried to stop Piankhy. In the Saite Period, Egyptians along with Greek and Carian mercenary soldiers sailed south for a campaign against the Nubians; one expedition is commemorated by Greek and Carian graffiti on the colossal statues of Ramesses II at the rock-cut temple of Abu Simbel.”

Transporting Stone by Boat in Ancient Egypt

According to PBS: “The Nile was used to transport supplies and building materials to the pyramids. During the annual flooding of the Nile, a natural harbor was created by the high waters that came conveniently close to the plateau. These harbors may have stayed water-filled year round. Some of the limestone came from Tura, across the river, granite from Aswan, copper from Sinai, and cedar for the boats from Lebanon.”

Steve Vinson of Indiana University wrote: “Egypt’s quarries required an extensive network of specialized loading docks, roads, and quays, and in some cases specialized vehicles, in order to get large building-stone out of the ground and to its designated construction sites. Massive objects like obelisks and monumental statues were even more difficult to handle. Although these operations cannot be reconstructed in detail and the methods used to carry them out no doubt varied considerably across space and time, various aspects of the process of moving stone are documented in, or inferable from, wall reliefs, documentary texts, or archaeological remains. [Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

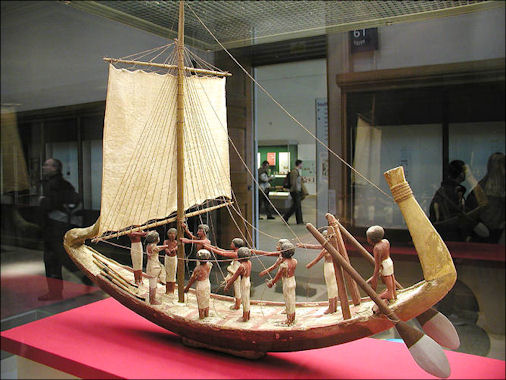

Boat from the Middle Kingdom

“Over relatively short distances, small loads of stone might be carried by donkey or even human porters. A road linking a gneiss quarry at Toshka in Nubia to the Nile River consisted of a track systematically cleared of gravel and debris, and marked with cairns and campsites, as well as the hoof-prints of the countless donkeys that had hauled gneiss along the 80-kilometer route . Very large stones, whether building blocks or finished objects like colossal statues or obelisks, were moved in the Pharaonic Period by sledges, which might have been used in conjunction with prepared hauling tracks. The most famous scene of such transport in action is the Middle Kingdom image of a colossal statue being hauled on a sledge to the tomb of Djehutyhotep at el-Bersha. This operation involved hauling the 80-ton statue no less than fifteen kilometers. The relief also shows another important detail: water being poured to lubricate the track over which the sledge is being hauled. However, sledges were, themselves, occasionally fitted with rollers or even wheels, and they might have been hauled by either men or draft animals.

“Over large distances, stone cargoes could only be hauled by river. Famous images of stone columns being conveyed for the construction of the Valley Temple of Unas (Fifth Dynasty) or the colossal obelisks of Hatshepsut show the transport of large stone cargoes on board ships, but precisely how such cargoes were loaded and unloaded has always been something of a mystery.

“In the Roman Period, when both ancient obelisks and exotic stone such as porphyry from Mons Porphyrites were exported to Italy, the logistical problems were of course even greater. Unlike the Pharaonic Egyptians, the Roman-era stone-haulers made use of wheeled vehicles, which might have been loaded from specially built loading docks. In one case, we hear of a 12-wheeled stone- hauling wagon, which was perhaps configured with four axels with three wheels each. Such a wagon may have had an axel-width of 2.8 meters; comparable-sized wagons are suggested by Roman-era wagon tracks discovered in the Eastern Desert.”

How Stone Was Transported by Boat in Ancient Egypt

No animals or machines were used to transport the blocks. Whenever possible the stones were transported on the Nile. Canals may have been used to get the stones as close to the site as possible. On the banks of the Nile, teams of perhaps 20 to 50 men hauled the stones on wooden sledges to the building sites where master carvers shaped each block and levered it into place. A hoisting machine was used to lift stones ("none of them were thirty feet in length") into place.

Steve Vinson of Indiana University wrote: In a discussion dating to the early Roman Imperial Period, Pliny the Elder describes his understanding of methods that had been used by Ptolemy II to load an obelisk some three centuries earlier. According to Pliny, the obelisk was said to have been laid across a canal, and two barges, loaded down with smaller stones so that they were heavy enough to pass below the obelisk, were maneuvered into position underneath it. The smaller stones were then removed from the transport ships until they were light enough to float the obelisks. The mention of two ships in this context has suggested to some that a sort of catamaran or double-hulled vessel was routinely used to move large stone cargoes. It seems likely that double-hulled ships were known in the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, but Pliny’s image as it stands seems improbable; Pharaonic images of the hauling of stone columns or obelisks show a single ship with the cargo parallel to the axis of the transport vessel. For the moment, the method or methods used by the Egyptians at any period to load barges with heavy columns, obelisks, or large sculptures remain unknown. [Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“One early method for moving stones by water, however, is suggested by the archaeological excavation of “Chephren’s Quarry,” a site some 65 kilometers northwest of Abu Simbel in the Western Desert. Featured here was a special, purpose-built loading ramp that may have been designed to receive an amphibious raft that could be drawn up out of the river and pulled on runners. According to the excavators of this site, it seems possible that stone would then be loaded from the loading ramp onto the amphibious raft, which could then be dragged back to the river and floated directly down- stream to construction sites in lower Egypt, without the necessity to load the stone onto boats.

“For the very largest cargoes, like the Hatshepsut obelisks, purpose-built ships were necessary. However, smaller quantities of building stone or brick might have been hauled by ships intended for general cargo. An entry in a Ramesside account ostracon is instructive: “The crew what was done by them, consisting of the emptying of the vessels that were under the authority of Penamun: seven vessels make 15 stones and 150 small bricks”.

Transporting Grain by Boat in Ancient Egypt

Grain is believed to have been hauled by donkey from farmsteads to embarkation points, where it was loaded onto ships by local workers. Steve Vinson of Indiana University wrote:“Middle-Kingdom granary models, such as the famous model from the tomb of Meket-Ra at Thebes, show individual porters with sacks of grain on their backs, emptying them out one at a time into silos. From there, grain would have eventually been unloaded and placed aboard transport vessels.” [Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

The Twentieth Dynasty Papyrus Amiens describes “a flotilla of some 21 vessels that appear to have been engaged in a major tax collection voyage, perhaps in the region of Assiut, where the papyrus itself was found. Each ship made multiple stops, embarking large quantities of grain, which were often accounted for in detail, according to the specific agricultural domain from which the grain came and according to the individual or group who were to be credited with supplying the grain. Occasionally, as in P. Amiens r. 4.1, we see grain transferred between ships, perhaps (but not certainly) due to vessels being disabled. Another important Ramesside papyrus, the “Turin Indictment Papyrus”, is notable for illustrating the opportunities for embezzlement that might present themselves to the operators of transport vessels hauling large amounts of grain.

“The transport of grain in the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods in Egypt is extensively documented in Greek papyrological sources. An instructive example is the Ptolemaic-era account papyrus Oxy 3, 522, which describes how boat captains recruited local labor through village elders to load 5,400 artabas (about 170 metric tons). Cargoes were often accompanied by persons known as naukleroi, whose function appears to have been to safeguard the cargo and organize transportation, not actually operate the ships in question. While the owner- operation of transport vessels is attested in the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, transport vessels might also owned by wealthy investors, particularly members of the Ptolemaic royal family , or by governmental institutions such as the office of the dioiketes, or finance minister.”

Religious and Ceremonial Uses of Boats in Ancient Egypt

Steve Vinson of the University of Indiana wrote: “The use of boats or images of boats for religious purposes is found throughout Egyptian history, from the Predynastic Period down to the end of Egypt’s traditional culture in the fifth century CE. One of the Egyptians’ central religious images was that of the continuous voyage of the sun god Ra through the sky in his two barks, the day bark and the night bark. The continual motion of the solar barks betokened the continued functioning of maat, the basic moral foundation of the entire universe, including the celestial realm. [Source: Steve Vinson, University of Indiana, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“One image of a blessed afterlife included joining Ra in his bark. Those traveling with Ra were assured of rebirth, as the Sun in his bark emerged every morning from the sky goddess Nut. As a result, images of boats are ubiquitous in tomb art, especially in the vignettes accompanying the underworld books in many royal tombs of the Egyptian New Kingdom, which show the many stages of the night voyage of the Sun.. In fact, the very first painted Egyptian tomb, Hierakonpolis Tomb 100 from the Gerzean/Naqada II Period, has a boat procession for its principle theme.

“There is no direct proof that the boats depicted in the Hierakonpolis tableau represent the bark of Ra or any associated barks, and many other interpretations have been offered, including the idea that the boat procession might be part of a Predynastic heb-sed ritual. However, the funerary context of the tableau makes the possibility of an association with the bark of Ra an appealing one. And in fact, one of the boats in the scene includes the image of a figure seated under a baldachin of the type that, in later Dynastic boat art, often encloses either a dead figure (e.g., the funerary boat models of Mekhet-Ra), or else Ra in one of his manifestations. Further, recent discoveries by John Darnell of Yale University of petroglyphs, presumably of late Predynastic date, that show boats traveling upside down suggest possible connections to the notion of metaphysical boats traveling in an inverted, night-time world even at this remote period.”

funerary paddling boat

Burying Boats with the Dead in Ancient Egypt

Steve Vinson of the University of Indiana wrote: “In the 1st Dynasty, the practice of burying boats with deceased kings and dignitaries began—a practice archaeologically documented from the 1st, 4th, and 12th Dynasties (the discovery in the summer of 2012 of a new 1st Dynasty boat at Abu Rawash, dated to the reign of King Den, see now also Ahram Online for 25 July 2012). Whether the boats buried in the 1st Dynasty were actually working vessels is unclear, since none of them has been completely excavated. However, the 4th Dynasty boats connected with the pyramid of Khufu were magnificent specimens of shipbuilding, and could certainly have sailed on the Nile. The first of the two surviving Khufu vessels was excavated and reassembled in the 1950s. The second, far less-well preserved, has been the subject of a project to excavate and restore it undertaken by Sakuji Yoshimura of Waseda University since 2011. [Source: Steve Vinson, University of Indiana, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“Both Khufu vessels were built of Lebanese cedar in the typical wjA-shape associated with divine boats and typical of ceremonial vessels built for gods and pharaohs. This design, especially with its decorative posts, seems intended to evoke the papyrus boats connected with the gods in Egyptian mythology. In the Pyramid Texts, either the green color or the actual papyrus construction of divine boats is mentioned with some frequency(the boat-types wAD and wAD-an, which Miosi takes as “green” and “beautiful in green” respectively, might as easily be taken to refer literally to papyrus). And at the far end of Egyptian history, a Demotic magical spell from the late Roman Period (prob. c. third century CE) refers to Osiris “upon his boat (rms) of papyrus (Dwf) and faience”.

“As noted above, it may be possible to link the Khufu vessels specifically to the category of dwA-tAwy, or “Praise of the Two Lands” vessels, known from textual sources as early as the 2nd Dynasty. According to the Palermo Stone, a number of such vessels had been built by Khufu’s father Sneferu, and the vessels’ descriptions are consistent with the actual characteristics of the Khufu vessels on a number of points, including shape, construction material, and general size.

“Aside from the ceremonial use of boats by kings, non-royal individuals used boats for religious purposes, particularly in pilgrimages. Among the best-documented of these was the so-called “Abydos voyage,” a ceremonial, posthumous boat voyage to worship Osiris at Abydos that is documented from the Middle Kingdom into the New Kingdom, most especially in tomb reliefs . It is not clear whether this was often or even ideally a real voyage, or whether the images of the “Abydos voyage” that appear in Middle and New Kingdom tombs were thought of as a sufficient substitute for an actual pilgrimage. On the other hand, use of boats is certainly documented for many other pilgrimages, including a Greco-Roman festival of the goddess Bastet described in Herodotus, 2.60. This famous description describes pilgrims raucously sailing down the Nile to Bubastis, singing, clapping, playing musical instruments and— most notoriously—sexually exposing themselves to on-shore spectators.

Funeral procession

“Boat models were often buried with dead aristocrats and kings. Some of these models were similar to other so-called “daily life” models that appear intended to assist the deceased in maintaining his accustomed lifestyle in the next world. But many such models were specifically “solar” or “funerary” in their design and must have been intended to evoke myths of the gods traveling in their barks, and the hope that the deceased would join them. The exceptionally fine fleet of Mekhet-Ra, today shared between the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and the Egyptian Museum of Cairo, illustrates the height of what Middle Kingdom Egyptian boat modelers could achieve. The vessels are notable for their painted and constructed detail, especially their rigging, although, like the vast majority of Egyptian boat models, the hulls of the Mekhet-Ra fleet were carved out of solid blocks of wood, not built of individual planks in such a way as to fully imitate working boats.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024