Home | Category: Old and Middle Kingdom (Age of the Pyramids) / Education, Health and Transportation / Economics

DIARY OF MERER

Rocks for the pyramid were quarried from as far as away in Aswan and the Red Sea were transported to Giza on boats down the Nile during the rainy season. A logbook with records detailing the construction of the pyramids of Giza and the transportation of stone there was discovered at the Red Sea harbor of Wadi al-Jarfin in 2013. Dated to about 4,500 years ago, making it the oldest papyrus document ever discovered in Egypt, the logbook was written in hieroglyphic letters on pieces of papyri by an inspector named Merer, who was "in charge of a team of about 200 men,"archaeologists Pierre Tallet and Gregory Marouard wrote in an article published in 2014 in the journal Near Eastern Archaeology. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science July 19, 2016 ^^^]

This papyri now known as Merer's Diary or the Diary of Mere. Tallet and Marouard wrote: "Over a period of several months, [the logbook] reports — in [the] form of a timetable with two columns per day — many operations related to the construction of the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Giza and the work at the limestone quarries on the opposite bank of the Nile," Tallet and Marouard wrote. ^^^

Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: “Merer recorded the logs in the 27th year of Khufu's reign. His records say that the Great Pyramid was near completion, with much of the remaining work focusing on the construction of the limestone casing that covered the outside of the pyramid. The limestone used in this casing, according to the logbook, was quarried at Tura near modern-day Cairo, and was brought to the pyramid site by boat along the Nile River and a system of canals. One boat trip between Tura and the pyramid site took four days to complete, the logbook notes. ^^^

“The logbook also says that in Khufu's 27th year, the construction of the Great Pyramid was being overseen by the vizier Ankhaf (also spelled Ankhhaf), the half-brother of Khufu. (A vizier was a high official in ancient Egypt who served the king.) The papyri also reveal that one of the titles Ankhaf held was "chief for all the works of the king," Tallet and Marouard wrote in the journal article. Though the logbook said Ankhaf was in charge during the pharaoh's 27th year, many scholars believe it's possible that another person, possibly the vizier Hemiunu, was in charge of pyramid building during the earlier part of Khufu's reign.” ^^^

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine: These papyri detail the activities of a group of some 40 men, known as a phyle, who were one of four such units that made up “The Escort Team of ‘The Uraeus of Khufu Is Its Prow. The discovery was highly serendipitous. Such records would normally have been brought back to the Nile Valley to be archived, but, for some reason, these documents were left at Wadi el-Jarf. The surviving papyri seem to have been originally buried in a pit between the limestone blocks and subsequently moved, most likely as part of an attempt to open the gallery. Those papyri that remained in the pit had largely decomposed after sitting in stagnant water, while those that were disturbed were saved for posterity. “This kind of narrative is very rare from the time,” says Tallet. “All the narrative texts we have from the Fourth Dynasty are basically biographical texts found in tombs. For the first time, we had something that was by a real person giving a precise and real account of their work. ” [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2022]

RELATED ARTICLES:

SHIPS AND BOATS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

TYPES OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN BOATS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

RIVER TRANSPORT AND USES OF BOATS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SEA TRAVEL IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Pyramid Builders of Ancient Egypt” by A. David (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Builders of the Pyramids” by Zahi Hawass (2009) Amazon.com;

“Mountains of the Pharaohs: The Untold Story of the Pyramid Builders” by Zahi Hawass (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Pyramids” by Mark Lehner (1997) Amazon.com;

“Giza and the Pyramids: The Definitive History” by Mark Lehner and Zahi Hawass (2017) Amazon.com;

“How the Great Pyramid Was Built” by Craig B. Smith (2018) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Ships and Shipping” by William Franklin Edgerton (2023) Amazon.com;

“Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World” by Lionel Casson (1995) Amazon.com;

“The Nile: History's Greatest River” by Terje Tvedt (2021) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Boats and Ships” by Steve Vinson (2008) Amazon.com;

“A Categorisation and Examination of Egyptian Ships and Boats from the Rise of the Old to the End of the Middle Kingdoms by Michael Allen Stephens (2012) Amazon.com;

“Ship 17 a Baris from Thonis-Heracleion” (Ships and boats of the Canopic Region in Egypt) by Alexander Belov (2018) Amazon.com;

"The Ancient Egyptians: Life in the Old Kingdom" by Jill Kamil (1998) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt” by Lionel Casson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The World of Ancient Egypt: A Daily Life Encyclopedia" by Peter Lacovara, director of the Ancient Egyptian Archaeology and Heritage Fund (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2016) Amazon.com

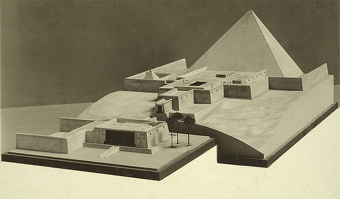

Bringing Pyramid Stones into Giza

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine: On a summer afternoon around 4,600 years ago, near the end of the reign of the pharaoh Khufu, a boat crewed by some 40 workers headed downstream on the Nile toward the Giza Plateau. The vessel, whose prow was emblazoned with a uraeus, the stylized image of an upright cobra worn by pharaohs as a head ornament, was laden with large limestone blocks being transported from the Tura quarries on the eastern side of the Nile. Under the direction of their overseer, known as Inspector Merer, the team steered the boat west toward the plateau, passing through a gateway between a pair of raised mounds called the Ro-She Khufu, the Entrance to the Lake of Khufu. This lake was part of a network of artificial waterways and canals that had been dredged to allow boats to bring supplies right up to the plateau’s edge. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2022]

As the boatmen approached their docking station, they could see Khufu’s Great Pyramid, called Akhet Khufu, or the Horizon of Khufu, soaring into the sky. At this point in Khufu’s reign (r. ca. 2633–2605 B.C.), the pyramid would have been essentially complete, encased in gleaming white limestone blocks of the sort the boat carried. At the edge of the water, perched on a massive limestone foundation, loomed Khufu’s valley temple, known as Ankhu Khufu, or Khufu Lives, which was connected to the pyramid by a half-mile-long causeway. When the pharaoh died, his body would be taken to the valley temple and then carried to the pyramid for burial. Nearby stood a royal palace, archives, granary, and workers’ barracks.

After offloading their cargo, the men anchored their boat in the lake alongside dozens — if not hundreds — of other boats and barges that had brought a variety of materials necessary to complete construction of the pyramid complex: granite beams from Aswan, gypsum and basalt from the Faiyum, and timber from Lebanon. Also arriving by boat were workers from across Egypt and cattle from the Nile Delta to feed them. As the sun set and twilight deepened, hearth fires twinkled on land and on many of the boats. Merer and his men settled in for a night’s sleep, after which they would head back to the quarries to pick up another load of limestone blocks. They would make two or three such round trips in the next 10 days.

For more on this See “Journeys of the Pyramid Builders” by Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2022 archaeology.org

Wadi al-Jarf — The Red Sea Pyramid Port

Wadi al-Jarf was a port and mining and seafaring town on the Red Sea, where copper used in the construction of the pyramids was mined and shipped to Gaza. It also appears that boats used to transport stones cut for the Great Pyramid of Giza were based here. José Miguel Parra wrote in National Geographic: The Wadi al-Jarf site consists of several different areas, spread over several miles between the Nile and the Red Sea. From the direction of the Nile, the first area, about three miles from the coast, contains some 30 large limestone chambers used for storage. It was in these caves that the papyri were discovered. [Source: José Miguel Parra, National Geographic, February 23, 2024]

Continuing east toward the sea for another 500 yards, a series of camps appears, and after those, a large stone building divided into 13 parallel sections. Archaeologists surmised that the building was used as a residence. Finally, on the coast is the harbor itself with dwellings and more storage spaces. Using pottery and inscriptions found at the site, archaeologists have been able to date the harbor complex to Egypt’s 4th dynasty, some 4,500 years ago. They believe the harbor was inaugurated in the time of Pharaoh Sneferu and abandoned around the end of his son Khufu’s reign. It was active for a short period, but during that time the port was devoted to building Khufu’s tomb, known then as Akhet-Khufu, meaning “Horizon of Khufu. ”

Along with the papyri, many other important archaeological finds there have revealed the importance of the port. Large structures, like the 600-foot-long stone jetty, show deep material investment in the area. Tallet and his team uncovered some 130 anchors, whose presence implies a busy harbor.

Connection Between Wadi al-Jarf and the Pyramids of Giza

Wadi al-Jarf is 120 kilometers south of Suez , which in turn is 125 kilometers west of Cairo, meaning than Wadi al-Jarf was a considerable distance form the Pyramids of Giza. Alexander Stille wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “ After visiting Wadi al-Jarf, Lehner, the American Egyptologist, was bowled over by the connections between Giza and this distant harbor. “The power and purity of the site is so Khufu,” he said. “The scale and ambition and sophistication of it—the size of these galleries cut out of rock like the Amtrak train garages, these huge hammers made out of hard black diorite they found, the scale of the harbor, the clear and orderly writing of the hieroglyphs of the papyri, which are like Excel spreadsheets of the ancient world—all of it has the clarity, power and sophistication of the pyramids, all the characteristics of Khufu and the early fourth dynasty.” [Source: Alexander Stille, Smithsonian Magazine, October 2015 |=|]

“The work that Tallet and his colleagues have done along the Red Sea connects with Lehner’s work at Giza....“Sailors may have figured among the visitors to the pyramid town, according to Merer’s papyrus journal. It mentions carrying stone both up to the lake or basin of Khufu and to the “horizon of Khufu,” generally understood to refer to the Great Pyramid. How did Merer get his boat close enough to the pyramids to unload his cargo of stone? Currently, the Nile is several miles from Giza. But the papyri offer important support for a hypothesis that Lehner had been developing for several years—that the ancient Egyptians, masters of canal building, irrigation and otherwise redirecting the Nile to suit their needs, built a major harbor or port near the pyramid complex at Giza. Accordingly, Merer transported the limestone from Tura all the way to Giza by boat. “I think the Egyptians intervened in the flood plain as dramatically as they did on the Giza Plateau,” Lehner says, adding: “The Wadi al-Jarf papyri are a major piece in the overall puzzle of the Great Pyramid.” |=|

“Tallet believes that the Lake of Khufu, to which Merer refers, was more likely located at Abusir, another important royal site about ten miles south of Giza. “If it is too close to Giza,” Tallet says, “one does not understand why it takes Merer a full day to sail from this site to the pyramid.” But Tallet has been persuaded by Lehner’s evidence of a major port at Giza. It makes perfect sense, he says, that the Egyptians would have found a way to transport construction materials and food by boat rather than dragging them across the desert. “I am not sure it would have been possible at all times of the year,” he said. “They had to wait for the flooding, and could have existed for perhaps six months a year.” By his estimate the ports along the Red Sea were only working for a few months a year—as it happens, roughly when Nile floods would have filled the harbor at Giza. “It all fits very nicely.”“ |=

Workers That Moved the Pyramid Stones from the Red Sea to Giza

Merer’s team of workers traveled across Egypt and were responsible for carrying out tasks related to the construction of the Great Pyramid and maybe not related to it. Alexander Stille wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: Merer and his crew “traveled from one end of Egypt to the other picking up and delivering goods of one kind or another. Merer, who accounted for his time in half-day increments, mentions stopping at Tura, a town along the Nile famous for its limestone quarry, filling his boat with stone and taking it up the Nile River to Giza. In fact, Merer mentions reporting to “the noble Ankh-haf,” who was known to be the half-brother of the Pharaoh Khufu and now, for the first time, was definitively identified as overseeing some of the construction of the Great Pyramid. And since the pharaohs used the Tura limestone for the pyramids’ outer casing, and Merer’s journal chronicles the last known year of Khufu’s reign, the entries provide a never-before-seen snapshot of the ancients putting finishing touches on the Great Pyramid.” [Source: Alexander Stille, Smithsonian Magazine, October 2015]

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine: The logbooks cover the phyle’s activities for just over a year near the very end of Khufu’s tenure. In the summer months, roughly June to November, the workers operated in the vicinity of Giza. The beginning of this period was the first month of the inundation season, called Akhet, corresponding to the arrival of the annual Nile flood. The phyle’s first assignment appears to have involved transporting around 600 workers to the Ro-She Khufu. There, Tallet believes, based on references in the logbooks to “works related to the dike of Ro-She Khufu,” “the dam of the entrance of Khufu’s lake,” and the team “lifting the piles of the dike,” these workers opened the floodgates to fill the basins and canals that allowed goods to be delivered to the foot of the pyramid complex construction site. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2022]

With these waterways open, Merer’s men then spent several months hauling loads of fine limestone blocks from the Tura quarries to the Giza Plateau. The team picked the blocks up from two separate quarries — Tura North and Tura South — alternating every 10 days so quarry workers had time to extract stone and pile up blocks in anticipation of their next visit. These blocks were the sort used to encase the Great Pyramid, but this late in Khufu’s reign, it’s believed that this work would already have been completed. According to Egyptologist Mark Lehner, director of Ancient Egypt Research Associates, the blocks were most likely used as roofing for one of the pits near the pyramid that held cedar boats that would be used in Khufu’s funeral. “If it’s that close to the end of Khufu’s reign, maybe they were delivering the Tura limestone blocks for covering those boat pits, which are where they buried the funerary hearse boats,” he says. “I think that’s what makes the most sense. ”

Log Records of Merer's Boatmen

Merer kept records of activities carried out over a three-month period during the construction of the Great Pyramid.

He recorded in great detail how the team retrieved them from the quarries of Tura and brought them by boat to Giza. A typical set of entries reads “Inspector Merer casts off with his phyle from Tura, loaded with stone, for Akhet Khufu; spends the night at She Khufu…. Sets sail from She Khufu, sails toward Akhet Khufu, loaded with stone; spends the night at Akhet Khufu.” [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2022]

One fragment from the diary records the three-day journey from the quarry to the pyramid’s site:

Day 25: Inspector Merer spends the day with his za [team] hauling stones in south Tura; spends the night in south Tura.

Day 26: Inspector Merer sets sail with his za from south Tura, laden with stone blocks, to Akhet-Khufu [the Great Pyramid]; spends the night in She-Khufu [administrative area with storage space for the ashlars, just before Giza].

Day 27: Embark at She-Khufu, sail to Akhet-Khufu laden with stones, spend the night at Akhet-Khufu. [Source: José Miguel Parra, National Geographic, February 23, 2024]

The next day, Merer and his workers returned to the quarry to pick up a new shipment of stones.

Day 28: Set sail from Akhet-Khufu in the morning; navigate up the river towards south Tura.

Day 29: Inspector Merer spends the day with his za hauling stones in south Tura; spends the night in south Tura.

Day 30: Inspector Merer spends the day with his za hauling stones in south Tura; spends the night in south Tura.

José Miguel Parra wrote in National Geographic: Merer’s diary even gives a glimpse of one of the pyramid’s architects. Ankhhaf, Khufu’s half brother, held the position of “head of all the king’s works. ” One of the papyrus fragments states: “Day 24: Inspector Merer spends the day with his za hauling [text missing] with people in elite positions, aper-teams, and the noble Ankh-haf, director of Ro-She Khufu. Merer also carefully kept track of how his crew was paid. Since there was no currency in pharaonic Egypt, salary payments were made generally in measures of grain. There was a basic unit, the “ration,” and the worker received more or less according to their category on the administrative ladder. According to the papyri, the workers’ basic diet was hedj (leavened bread), pesem (flat bread), various meats, dates, honey, and legumes, all washed down with beer.

from Secrets of the Pyramids secretofthepyramids.com

Activities of Merer Boatmen During the Down Season

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Hundreds of ceramic storage jars were found in galleries such as this one at Wadi el-Jarf. The jars were used to hold water and transport goods to and from the Sinai Peninsula. In December, when the Nile flood had ebbed and transporting heavy loads by boat to the Giza Plateau was no longer feasible, Merer’s phyle was sent to an area of the Nile Delta near a pair of towns. The names of these towns — Ro-Wer Idehu, or the Great River Mouth in the Marshes, and Ro-Maa, or the True River Mouth — likely refer to points where one or more of the Nile’s branches opened into the Mediterranean. There, the team was tasked with “tamping” or “compacting” a structure called a “double djadja,” which Tallet believes was likely a jetty of the sort uncovered at Wadi el-Jarf. Such a structure would have supported maritime expeditions to the Levant to obtain, among other materials, pine and cedar, which were generally unavailable in Egypt but were essential for making boats and stoking the fires used to process copper ore. “At that time in history, the Egyptians were trying to connect as much as they could with the outer world,” says Tallet. Ensuring the team did not go hungry or thirsty during this remote posting, the papyri note that an official named Imery made several trips to fetch rations of bread and beer. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2022]

The papyri include no mention of the phyle’s activities from January through March, and Tallet believes this may have been a season when the workers could return home to spend time with their families. Starting in April, the phyle appears to have been working at Wadi el-Jarf. While the logbooks covering this period are quite fragmentary, they do mention sailing expeditions, as well as a place called Ineb Khufu, or Walls of Khufu, which may refer to the el-Markha fortress. Given that the phyle came to Wadi el-Jarf at the beginning of the Red Sea sailing season, which continued through the end of the summer, they were likely tasked with getting the harbor up and working again. This would have involved moving or smashing the limestone blocks that sealed the galleries, reassembling boats, and making sure they were seaworthy. Only then could they launch their boat with its uraeus prow to ferry miners, goods, and copper back and forth between the harbor and the Sinai. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2022]

Were the Merer Boatmen Highly Skilled, Well Paid and Close the Pharaoh?

Working on royal boats seems, was a source of prestige. According to Merer's Diary the laborers ate well, and were provisioned with meat, poultry, fish and beer. Among the inscriptions that Tallet and his team found at the Wadi al-Jarf gallery complex is one, on a large jar fashioned there, hinting at ties to the pharaoh; it mentions “Those Who Are Known of Two Falcons of Gold,” a reference to Khufu. “You have all sorts of private inscriptions, of officials who were involved in these mining expeditions to the Sinai,” Tallet says. “I think it was a way to associate themselves to something that was very important to the king and this was a reason to be preserved for eternity for the individuals.” Clearly these workers were valued servants of the state. |=|

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Based on the contents of the papyri, Tallet believes that at least some workers in the time of Khufu were highly skilled and well rewarded for their labor, contradicting the popular notion that the Great Pyramid was built by masses of oppressed slaves. In several instances, Merer and his team were awarded gifts of textiles. In addition to a diet including poultry, fish, fruit, and a variety of breads, cakes, and beers, the men were also provided with dates and honey, delicacies that were extremely scarce and generally reserved for those within the royal entourage. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2022]

In fact, the laborers may have been quite close to the royal family. During their several months working at the Giza Plateau, Inspector Merer’s phyle — and possibly other phyles that were part of the same group — appears to have taken turns guarding and helping to provision a royal institution called Ankhu Khufu, which likely referred to Khufu’s valley temple. In the papyri, Merer’s men are called the setep za, “the chosen phyle” or “the elite,” a phrase that can denote a royal guard force. “I think these boatmen were a very special category of workers because their activities were really vital for the royal project,” says Tallet. “I think the monarchy had an interest in being fair to them because it was essential to have them working well. ”

The first thing the researchers noticed when they found the texts with Merer’s Diary was the frequent presence of Khufu’s cartouche, an oval containing the pharaoh’s name, which helped establish that the site was used during his reign. As they looked further, they concluded that the texts consist of the names of work gangs that operated the harbor, such as “The Escort Team of ‘Great Is His Lion’” and “The Escort Team of ‘Khufu Confers on It His Two Uraei. ’” “It took some time to understand what these names meant,” says Tallet. “But in the end, we figured out that these teams were probably named after the boats to which they were linked. And each boat was named from a royal insignia that it bore. ” Thus, Inspector Merer’s “Escort Team of ‘The Uraeus of Khufu Is Its Prow,’” which was found written on hundreds of storage jars, apparently crewed a boat whose prow was decorated with the snake ornament worn by the king. The researchers would soon learn much more about these particular laborers.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last Updated August 2024