Home | Category: Death and Mummies

PHARAOH'S FUNERAL

The day before a Pharaoh’s funeral the king's mummy was placed in the royal palace to lie in state. On the day of the funeral itself the Pharaoh's widow stood at the mummy's feet reciting formulas of rebirth. Then a procession carried the coffin to a temple for four days of rituals.

After this the deceased pharaoh was taken to his tomb. His successor touched his mouth and eyes to open them for eternal life; burial furniture was brought in, and the king's coffin was set upright; and finally the tomb was sealed. Usually the first thing the new pharaoh did when he claimed the throne was erase the name of his predecessor on all the monuments in the empire and replace them with his own.♀

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

”Burial Customs in Ancient Egypt: Life in Death for Rich and Poor”, Illustrated,

by Wolfram Grajetzki (2003) Amazon.com;

“Death and Burial in Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2015) Amazon.com

“Pharaoh's Boat” by David Weitzman Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt’s Most Famous Royal Family: The Lives and Deaths of Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and Tutankhamun” by Charles River Editors (2019) Amazon.com;

”Private Lives of the Pharaohs: Unlocking the Secrets of Egyptian Royalty” by Joyce Tyldesley (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Pharaohs” by Joyce Tyldesley (2009) Amazon.com;

“Pharaohs: The Rulers of Ancient Egypt for Over 3000 Years” by Dr Phyllis G Jestice (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Pharaohs of Ancient Egypt” by Elizabeth Payne (1981) Amazon.com;

“Egypt: People, Gods, Pharaohs” by Rose-Marie Hagen, Rainer Hagen (2009) Amazon.com;

“Kingship, Power, and Legitimacy in Ancient Egypt: From the Old Kingdom to the Middle Kingdom” by Lisa K. Sabbahy (2004) Amazon.com;

“The Egyptian Book of the Dead (Penguin Classics) by Wallace Budge and John Romer (2008) Amazon.com;

“Osiris and the Egyptian Resurrection, (Volume 1), Illustrated, by Sir Ernest Alfred Thompson Wallis Budge (1857-1934) Amazon.com;

“The Complete Valley of the Kings: Tombs and Treasures of Egypt's Greatest Pharaohs” (1996) by C. N. Reeves, Richard H. Wilkinson, Nicholas Reeves,

Amazon.com;

King Tut’s Funeral

Ann R. Williams wrote in National Geographic History: The series of paintings on the four walls of Tutankhamun’s tomb are a story — and a kind of map to help guide King Tut to the afterlife. Beginning with his funeral, they show his long journey and the gods and goddesses who will greet him along the way. [Source: Ann R. Williams, October 19, 2022]

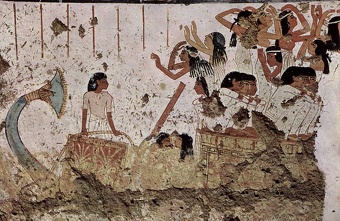

This is where the story of Tutankhamun’s afterlife begins. His mummy lies on a funerary shrine pulled by mourners dressed in white. At the end of the groups of mourners are two men with shaved heads, probably the viziers of Upper and Lower Egypt. Another mourner toward the back may be General Horemheb. He was the head of the army and would eventually come to the throne after the death of King Tut’s successor, Aye.

The first scene on the right of the north wall likely shows Aye dressed in a leopard skin, the garment of a sem priest. That official performed a ceremony called the “opening of the mouth” to reanimate all the senses of the deceased for the life he would lead in the next world. King Tut appears in the form of Osiris, the king of the afterworld, and Aye works on him with a special tool. To the left, Nut, the sky goddess, greets King Tut. In her hands she holds two black zigzag signs, symbols of cool waters and celebration that welcome him to the afterlife.

The ancient Egyptians believed that every night, the sun had to pass through 12 hours of darkness before it was resurrected in the morning. They also believed the king had to make the same journey to the afterworld. In Tut’s tomb, the upper left side of the west wall shows the boat that carried the sun through that dark journey. A scarab beetle representing the sun rides in the vessel. Beneath that scene are rows of seated baboons that symbolize the first hour after sunset, the beginning of the night through which the sun — and King Tut — had to pass.

On the right side of this wall, Hathor, the goddess of the west, stands in front of Tutankhamun. She holds two ankhs, symbols of everlasting life, and she offers one to the king — in other words, he will now live forever in the great beyond. Anubis, the god of embalming, appears behind Tut also holding an ankh. The left side of this wall is missing because it was shattered when Howard Carter broke through the wall to get into the burial chamber. The scene that was destroyed showed Isis, the wife of Osiris, welcoming King Tut the same way Nut does on the north wall, with the zigzag symbols on the palms of her hands.

Ships and the Pharaoh’s Funeral

Ships played a central role in the funerals of pharaohs. The Egyptians believed that royal barges carried the pharaohs to heaven and believed the sun-god Ra traveled through the sky during the day and the netherworld at night in a boat. Boats were buried near pharaohs so they could do the same thing for them. Perhaps more than anything else these vessels showed importance in ancient Egypt of boats — the primary source of transportation up and down the Nile, where the ancient culture was centered.

The Pharaohs’ funerals ships were often very large and were buried with great care in elaborate tombs. Only a few such tombs have been discovered. The whole exercise was so expensive and was likely only done for particularly wealthy or esteemed pharaohs.

Images of boats first appeared in 3200 B.C. Ancient boats that were 4,900 year old were found in the graves of the first pharaohs.

An Egyptian shipwreck that produced a gold scarab with Queen Nefertari's name was dated with tree rings from logs in ship to 1316 B.C. A jewel encrusted pendant found in King Tutankhamun’s tomb featured a jeweled boat topped by jeweled baboons and scarabs. Objects found with buried funerary boats include miniature “solar barks,” with symbols of the sun gods.

See Separate Article: TYPES OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN BOATS africame.factsanddetails.com

Royal Bark of Khufu

One of the most spectacular objects found at the pyramids of Giza other than the pyramids themselves was the royal bark of Khufu, a 142-foot-long boat excavated from one of five large carved rock chambers on the east side of the Pyramid of Cheops. Hieroglyphics inside the chambers where the boat were found seem to indicate it were was by Khufu’s son Djedefre. The royal bark is now displayed in the boat museum near the Great Pyramid of Khufu. [Source: Farouk El-Baz, Peter Miller, National Geographic, April 1988]

The royal bark of Khufu was made up of 1,224 components and was found in a pit that was 102 feet long, 11½ feet deep and 8 ½ wide. The planks of the boat were sewn together transversely (most sew ships are sewn together longitudinally). The rudderless boat was propelled and steered by ten 26-foot oars. It has narrow beam and a high, elegantly tapered stem and stern posts, a deck house, four pointed oar blades. The design is similar to that of papyrus river crafts. There was no sign of any masts, sails or rigging.

Archaeologists are not sure what the vessel was used for. Many think it was the sacred boat buried by Khufu’s son Djedefre for use by the dead pharaoh in the afterlife or to carry him on his journey in the afterlife. Others believe it carried the mummified body of Cheops from Memphis to Giza. To get the boat inside the entrance to the chamber it was taken apart and reassembled inside the tomb. There is evidence that boat was used in the water (marks in pieces left by the ropes used to bid the ship together).

Funeral of a Mummy by Frederick Arthur Bridgman

Did King Tutankhamun Have A Funeral Meal?

Dorothea Arnold of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “In 1941, Herbert Winlock proposed that the floral collars and most of the above-described pottery vessels were used at a meal. In reconstructing this event, Winlock was much influenced by the ubiquitous depictions of banquets in Dynasty 18 Theban tombs. But the German Egyptologist Siegfried Schott demonstrated that these images in fact illustrate not a funeral feast but a festival that was celebrated annually in ancient Thebes (present-day Luxor). During this feast—called "The Beautiful Feast of the Valley"—an image of the god Amun was conveyed from his temple at Karnak on the east bank of the Nile to the cemeteries and temple area on the west bank. While the image rested overnight in the sanctuary, people feasted in and in front of the tombs of their ancestors. This "Feast of Drunkenness" was not a celebration at a funeral but a religious festival that included the dead of the community. The objects and vessels in KV 54 cannot have anything to do with this occasion, since they were buried together with mummification leftovers. [Source: Dorothea Arnold, Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2010, metmuseum.org \^/]

“New Kingdom Theban reliefs and paintings reveal, however, that another meal, this one of a more sedate character, took place at a funeral in connection with rites performed for the deceased's statue, another important item in Egyptian funerals that provided a place of materialization for a dead person's soul. These statue rites are repeatedly depicted to have been enacted in a garden setting, with food offerings set out on tables and drinks in large jars like some found in KV 54 resting under canopies. \^/ “Interestingly—and importantly for an interpretation of the objects from KV 54—some representations of statue rites also show that after the conclusion of these rites, all vessels used for offerings were smashed. Almost all pots in the KV 54 find were found broken into pieces. It can, therefore, be suggested that the above-described vessels and other remains of food (such as animal bones) from KV 54 were part of a display of food offerings set out at the consecration of a statue of King Tutankhamun. As was customary in antiquity, the participants in the offering ritual would have consumed the food after the ceremonies were concluded. Communal meals in the presence of a deceased's effigy are, moreover, known to have taken place in many cultures and are certainly attested to have taken place in Roman Egypt. \^/

“Winlock assumed that the floral collars were worn by the participants of a funeral meal. It is, however, more probable that a number of floral collars were created to adorn the various coffins—and maybe images—of the king. One large example made of a very similar choice of plants as the one found on the three Museum collars was eventually placed on Tutankhamun's innermost coffin and found there by Howard Carter; the others would then have been stored away among the leftovers of the embalming process.” \^/

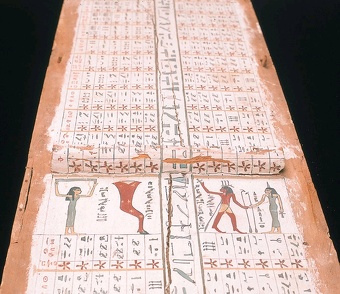

Funeral boat

Tutankhamun's Mortuary Temple, the Site of His Mummification and Statue Rites?

Dorothea Arnold of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The mummification and statue rites for a king were held, not in front of the king's tomb in the Valley of the Kings, but more likely at the site of the king's mortuary temple. Mortuary temples were built by the pharaohs of the New Kingdom for the daily celebration of their cult after death as well as the worship of Amun, the supreme god of Thebes, and other deities; and all of these temples were situated close to the agricultural land east of the Valley of the Kings. [Source: Dorothea Arnold, Department of Egyptian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2010, metmuseum.org \^/]

“We do not know where Tutankhamun’s mortuary temple stood and whether it was ever fully completed. A relief in the Museum (05.4.2) depicting a man called Userhat, who is said to have served at Tutankhamun's mortuary temple, is the only evidence extant that a cult ever took place there. A site for the temple, however, must certainly have been chosen and prepared by the time of the king's funeral, and it is there that both his mummification and statue rites most probably took place.\^/

“This explains not only why the leftovers of the king's mummification were packed up together with the remains of offerings dedicated to his statue, but is also congruent with the garden settings in which the statue rites are depicted. In the end, the whole lot (mummification leftovers and food offering remains) were then conveyed in their large containers from the mortuary temple site to the Valley of the Kings together with all the other articles that would fill the king's tomb.” \^/

Well-Provisioned Tomb for Pharaoh

Ann R. Williams wrote in National Geographic History: The tombs of the elite were often prepared long before their death. When the time came, important individuals were placed in multiple coffins, some beautifully decorated. Some were then interred in elaborate stone sarcophagi. Confident that their tombs were the gateways to the next world, Egyptians stocked them with everything they would need: food, wine, clothing, furniture, and other essentials for the journey ahead. “Beautify your house in the Necropolis and enrich your place in the West,” said Prince Hordedef, a renowned sage of the 4th dynasty. “The house of death is for life.” [Source: Ann R. Williams, October 19, 2022]

Animal mummies also accompanied ancient Egyptians in their tombs — shrews in boxes of carved limestone, rams covered with gilded and beaded casings, and ibises in bundles of intricate appliqués. Even tiny scarab beetles and the dung balls they ate have been found. Some of these animals were pets, preserved so deceased humans would have companionship in eternity. Others, cut into portions, served as perpetual meals for the people they were buried with. Still others were votive offerings meant to carry prayers to the gods or were reverently laid to rest as the living representative of a god.

Magnificent treasures were buried with the rich and royalty, assuring a successful afterlife, like the gold, glass, and semiprecious stone earrings buried with Tut. Tut’s mummy wore gold sandals. Gold represented the skin of the immortal gods and symbolized everlasting life. A statue of the god Ptah was found in the chamber known as the Treasury. It had a garland of pomegranate leaves around its neck and was wrapped in linen.

In the tomb lay the head of a cow, partly gilded and painted with resin, that represents the goddess Hathor. A gilded lion goddess with inlaid blue glass and brown crystal eyes adorned a ritual bed in the tomb’s Antechamber.A drinking cup of translucent calcite was carved in the shape of an open lotus blossom, a symbol of rebirth.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024